Abstract

Vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) affects 1 of 200 to 400 neonates who do not receive vitamin K prophylaxis. VKDB is classified by cause (idiopathic or secondary) and type (early, classic, late). The late type of VKDB is the least common and most severe with a mortality rate of 20%. AAP recommends that all neonates should receive a single dose of vitamin K1 soon after birth, which includes 0.5 to 1.0 mg of intramuscularly administered vitamin K1 or 1 to 2 mg of oral vitamin K1. Intramuscular administration is preferred and has more benefits than oral administration. The oral prophylaxis administration is controversial and in our Country is not available.

Introduction

Hemorrhagic disease of newborns affects 1 of 200 to 400 neonates who do not receive vitamin K prophylaxis. It has been associated with vitamin K deficiency since 1961 when the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended the injection of vitamin K to all newborns [1].

Vitamin K is a procoagulant cofactor for some of the factors (II, VII, IX, X) in the coagulation cascade, it is necessary to form the activation of precursor proteins of the specific factors, but it is not important in the synthesis of clotting factors [2].

The physiologic balance of the procoagulant and anticoagulant factors is age dependent. So healthy term newborns have naturally reduced levels of vitamin K–dependent clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X because vitamin K1 has poor placental transfer to the fetus [3]. In addition to low plasma levels neonates have a significantly lower storage capacity of vitamin K1 which is quickly used in the first hours of life [4]. In 2016 Philippi et al, demonstrated that the principal source of vitamin K1 in children is an adequate diet, but breastfed newborns do not receive sufficient vitamin K1 from feeding because breast milk is low in vitamin K1. Also, breast milk is poor in vitamin K2 because it has Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species, which do not produce vitamin K2 in the intestinal flora [5]. This idea was previously mentioned by Lippi & Franchini in 2011, when they emphasized the vulnerability of newborns due to the lack of vitamin K, especially in the first days of life [6].

Analyzing the characteristics of vitamin K (low storage capacity, poor placental transfer, a short half-life, and the near absence in breast milk) we can say that newborns are the ideal population for vitamin K prophylaxis for VKDB.

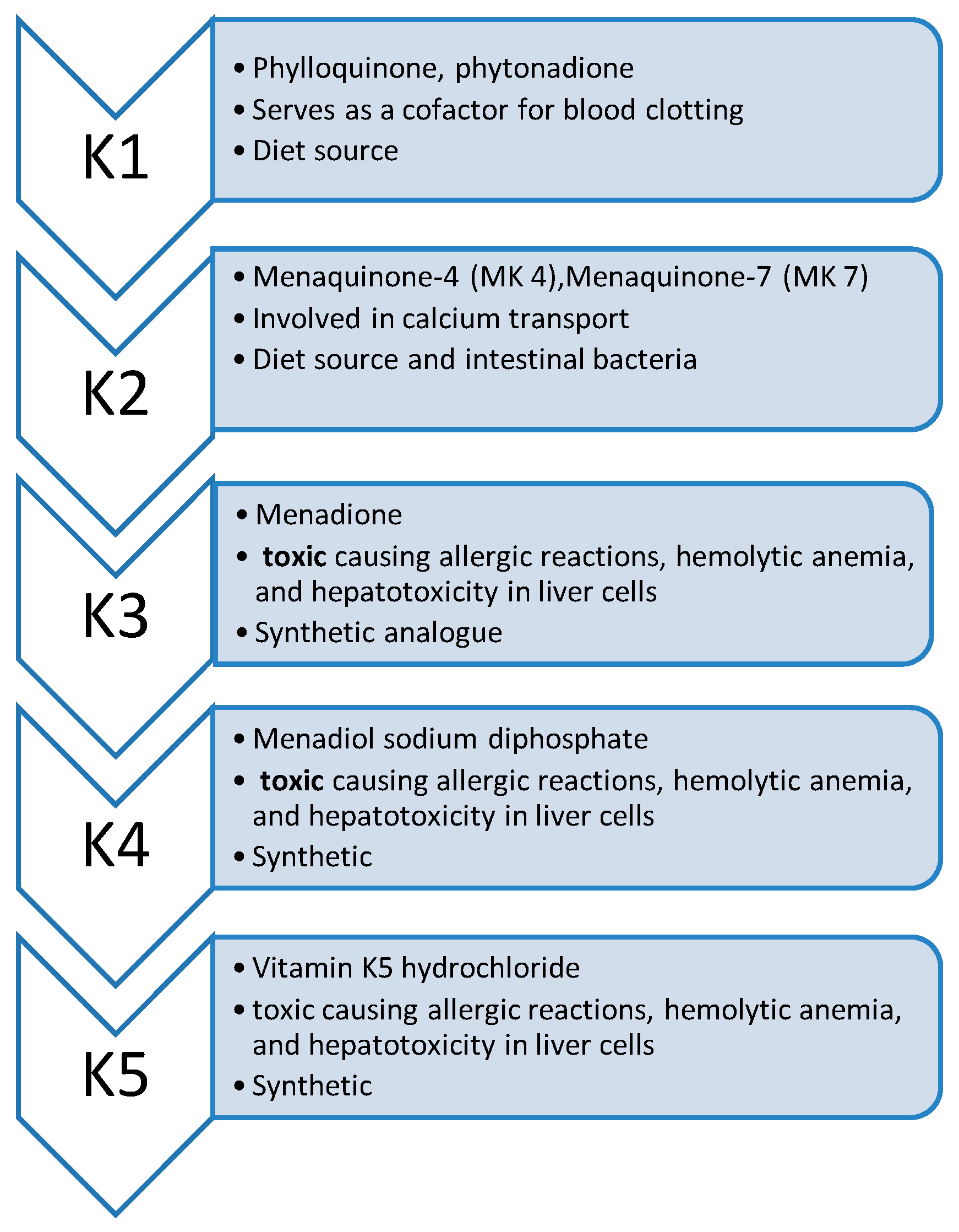

Types of Vitamin K

Five types of vitamin K are known with roles in the human body and are listed in Table 1. In 2017 Yamanashi demonstrate that intramuscular absorption of vitamin K in neonates seems to be the most efficient and does not interfere with liver metabolism [7]. Nowadays, the most used form for injection in newborns is a synthetic version of vitamin K1. The shot contains phytonadione 2-10 mg as the active ingredient and also inactive ingredients such as polyoxyethylene fatty acid derivative, dextrose, water, and benzyl alcohol as a preservative. We must mention that since 2002 there has been a preservative-free version on the market [8].

Table 1.

Types of VKDB.

Clinical aspects and classifications of VKDB

Infants may develop vitamin K deficiency by day 2 or 3 and they need parenterally administration of vitamin K in the first hours of life. Hemorrhagic disease of newborns occurs typically at 48 hours of life, in neonates that didn’t receive vitamin K and can cause gastric or intracranial hemorrhage, which can be observed through clinical aspects such as seizures, brain damage, or death [9,10].

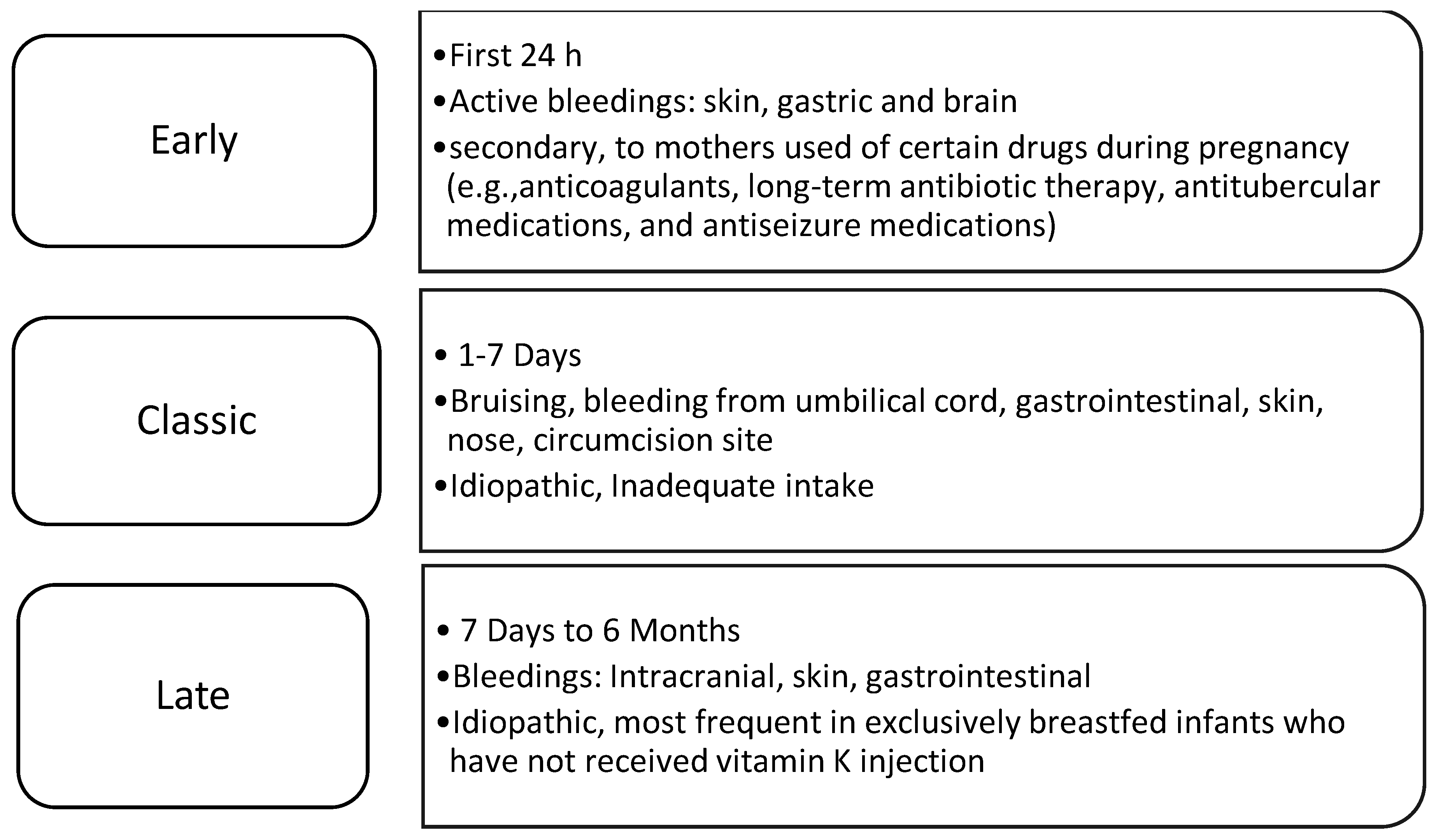

VKDB is classified by cause (idiopathic or secondary) and type (early, classic, late) and is specified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Types of Vitamin K.

Every type of VKDB can cause serious complications for healthy newborns. Early-onset VKDB can be quite severe, with the presence of cephalic hematoma, and intracranial and intraabdominal hemorrhages [6]. Some studies concluded that infants with known fetal exposure to certain drugs (antiepileptic, antituberculosis medications, anticoagulants, and long-term antibiotic use) have an increased incidence of bleeding between 6% and 12% in the first hours of life [3].

Classic VKDB is linked to insufficient feeding by the newborn [6] and is rarely seen with prophylactic vitamin K administration at birth [3]. The clinical presentation involves bleeding at the umbilical cord, gastrointestinal bleeding, circumcision site bleeding, generalized ecchymosis, and, very rarely, intracranial bleeding [11].

The late type of VKDB is the least common and most severe with a mortality rate of 20%. Clinical presentation includes more generalized symptoms in the newborn, such as fussiness, emesis, seizures, lethargy, feeding difficulties, and bulging fontanelles [5]. Up to 60% of neonates affected by late VKDB have intracranial hemorrhage [5], and 40% will have long-term neurologic morbidity [12].

Prophylactic Vitamin K Injection for Newborns and treatment for VKDB

The first recommendation for the prophylactic administration of vitamin K to prevent VKDB was issued in 1961 by the American Academy of Pediatrics, since then the prophylactic use of vitamin K has been in place for decades, and the different practices of this prophylaxis for the term and preterm infants vary widely across the globe, including different doses and routes [13]. Also, the AAP recommends that vitamin K1 has to be given to all newborns as a single, intramuscular dose of 0.5 mg to 1 mg in the first 6 hours after birth. In 2014 Schulte et al., recommended the administration of 1 to 2 mg of oral vitamin K1 instead of injection.

Nowadays the AAP continues to recommend the administration of intramuscular prophylaxis of vitamin K1 to all newborns [13] because it has been established that some infants may have trouble absorbing the oral version.

In addition, when VKDB is strongly suspected, the treatment is 1 mg of vitamin K1 intramuscularly and the newborn is quickly stabilized within 2 to 3 hours of administration, with an increase in vitamin K–dependent coagulation factors between 2 and 30 minutes. In the case of a severe hemorrhage, whole blood, and fresh frozen plasma transfusions are indicated [12].

Oral Vitamin K for VKDB prophylaxis

In the last years, more parents prefer oral vitamin K prophylaxis for their newborns because it is easy to administer and provides a pain-free alternative. Oral administration is very controversial. In 2018 Ng & Loewy published the results of their study where the incidence of late VKDB varies from 1.6 to 6.4 per 100,000 when oral vitamin K was used in comparison with a single intramuscular dose where the incidence of late VKDB was 0.25 per 100,000 [14].

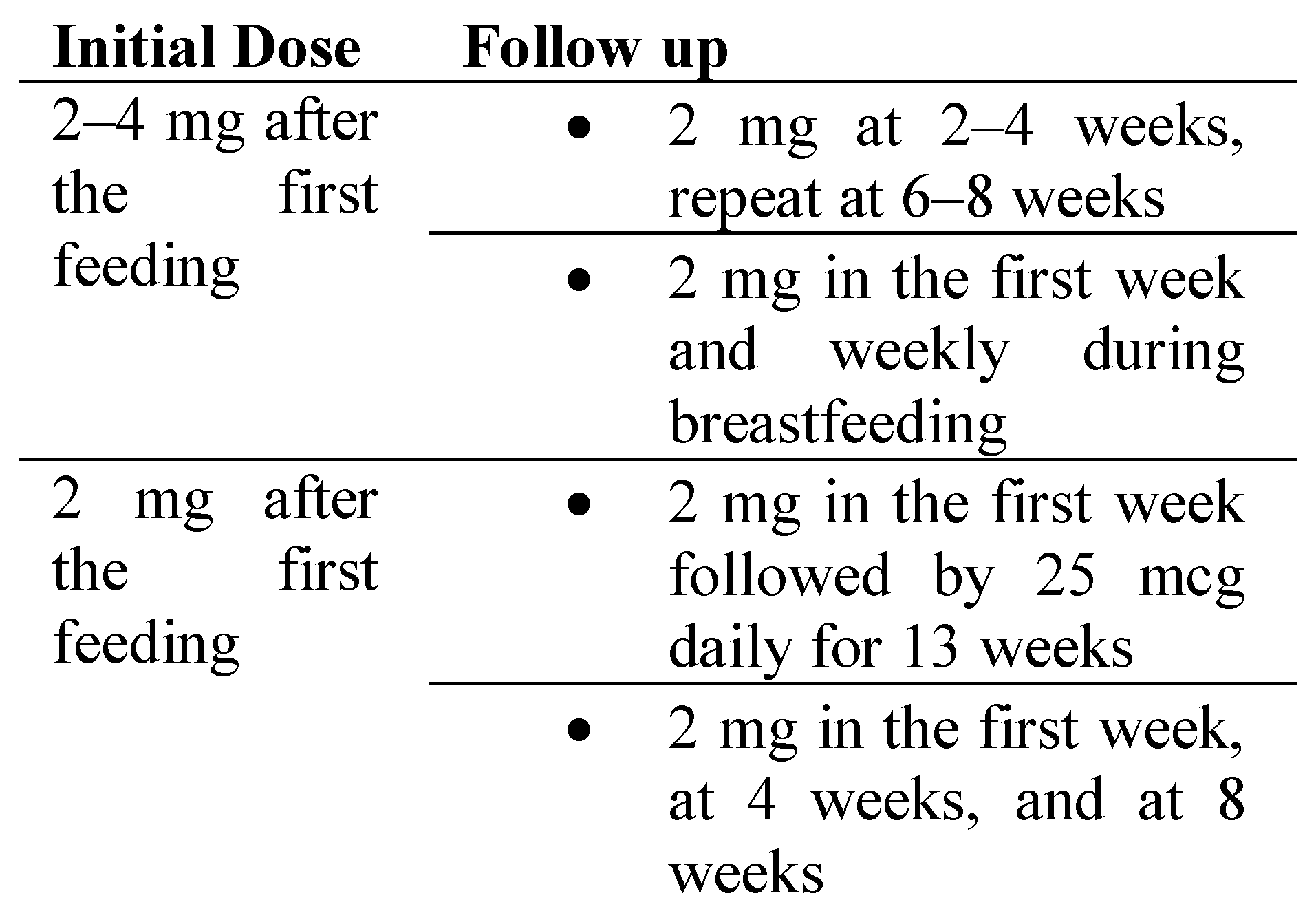

In the United States, oral vitamin K does not require FDA approval and so the is no evidence of the recommended dosage. Parents requesting oral vitamin K prophylaxis should note that the dosage and schedule for the best efficacy are not well established. Table 3 there are presented some suggested dosages of oral vitamin K for newborns [15].

Table 3.

Oral vitamin K dose [16].

Ceratto & Savino in 2019 emphasized the importance of correct administration and doses if parents choose to use oral vitamin K1 prophylaxis [17]. As Mihatsch et al said in 2016, oral vitamin K should be encouraged to be given during feeding and to monitor that the newborn does not spit up after the administration. If spitting occurs within an hour of administration parents should repeat the dose [18]. Oral vitamin K prophylaxis is not recommended in newborns with pathologic conditions that affect how liposoluble vitamins are absorbed or conditions that favor bleeding.

The standard and recommended dose and route of vitamin K for newborns differ according to the availability of each country. A comparative study performed by Berendse et al., using different routes of vitamin K administration has demonstrated that oral vitamin K is not an option in countries where is not on the market and has lower benefits than intramuscular administration [8]. A study from 2019 showed the benefit of increasing the oral vitamin K prophylaxis dose in reducing the incidence of VKDB, but it’s still poor compared to the efficacy of intramuscular prophylaxis [20].

Parental Concerns about Vitamin K prophylaxis

Although the benefits of intramuscular vitamin K prophylaxis are very well known, in the last decade there has been a rising opposition from parents. Marcewicz et al., publication in 2017 a study that presented the reasons for parental refusal of newborn vitamin K prophylaxis and they found that parents refused vitamin K because it seemed unnecessary, unnatural, or not safe for the newborn in the injectable form, the preservatives or ingredients used in the injection, possible adverse reactions, or the amount of possible pain [9].

It’s important that the nurse or the neonatologist explain the risks of VKDB as well as the risks and benefits of the administration of vitamin K to the parents.

Conclusion

Since the 1960s, it has been demonstrated that the prophylactic intramuscular administration of vitamin K can be lifesaving in VDKB diseases. In addition, the single intramuscular injection of 0.5-1 mg soon after birth for all newborns is preferred over oral administration. In our country, the intramuscular injection of 1 mg of vitamin K1 is performed.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Controversies concerning vitamin K and the newborn. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Pediatrics 2003, Jul. 112, (1 Pt 1). 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strickland, S.W.; Burns, E.; Palkimas, S.; Bazydlo, L.A.L. The sample that would not clot. Clin Chim Acta. 2018, Oct. 485, 272–274, Epub 2018 Jun 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchili, M.R.; Santoro, E.; Marchesi, A.; Bianchi, S.; Rotondi Aufiero, L.; Villani, A. Vitamin K deficiency: a case report and review of current guidelines. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018, Mar 14. 44(1), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holley, S.L.; Green, K.; Mills, M.; Detterman, C.; Rappold, M.F.; Thayer, S. Educating Parents on Vitamin K Prophylaxis for Newborns. Nurs. Womens Health 2020, Aug. 24(4), 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillippi, J.C.; Holley, S.L.; Morad, A.; Collins, M.R. Prevention of Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2016, Sep. 61(5), 632–636, Epub 2016 Jul 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Franchini, M. Vitamin K in neonates: facts and myths. Blood Transfus. 2011, Jan. 9(1), 4–9, Epub 2010 Sep 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yamanashi, Y.; Takada, T.; Kurauchi, R.; Tanaka, Y.; Komine, T.; Suzuki, H. Transporters for the Intestinal Absorption of Cholesterol, Vitamin E, and Vitamin K. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2017, Apr 3. 24(4), 347–359, Epub 2017 Jan 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Araki, S.; Shirahata, A. Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding in Infancy. Nutrients 2020, Mar 16. 12(3), 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marcewicz, L.H.; Clayton, J.; Maenner, M.; Odom, E.; Okoroh, E.; Christensen, D.; Goodman, A.; Warren, M.D.; Traylor, J.; Miller, A.; Jones, T.; Dunn, J.; Schaffner, W.; Grant, A. Parental Refusal of Vitamin K and Neonatal Preventive Services: A Need for Surveillance. Matern Child Health J. 2017, May. 21(5), 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sahni, V.; Lai, F.Y.; MacDonald, S.E. Neonatal vitamin K refusal and nonimmunization. Pediatrics 2014, Sep. 134(3), 497–503, Epub 2014 Aug 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majid, A.; Blackwell, M.; Broadbent, R.S.; Barker, D.P.; Al-Sallami, H.S.; Edmonds, L.; Kerruish, N.; Wheeler, B.J. Newborn Vitamin K Prophylaxis: A Historical Perspective to Understand Modern Barriers to Uptake. Hosp. Pediatr. 2019, Jan. 9(1), 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, R.; Jordan, L.C.; Morad, A.; Naftel, R.P.; Wellons, J.C.; Sidonio, R. Rise in late onset vitamin K deficiency bleeding in young infants because of omission or refusal of prophylaxis at birth. Pediatr. Neurol. 2014, Jun. 50(6), 564–568, Epub 2014 Feb 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardell, S.; Offringa, M.; Ovelman, C.; Soll, R. Prophylactic vitamin K for the prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding in preterm neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018, Feb 5. 2(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ng, E.; Loewy, A.D. Position Statement: Guidelines for vitamin K prophylaxis in newborns: A joint statement of the Canadian Paediatric Society and the College of Family Physicians of Canada. Can. Fam. Physician. 2018, Oct. 64(10), 736–739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shearer, M.J. Vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) in early infancy. Blood Rev. 2009, Mar. 23(2), 49–59, Epub 2008 Sep 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subspecialty Group of Neonatology, the Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association; Society of Neonatology, Gansu Medical Doctor Association; Clinical Epidemiology and Evidence-based Medicine Branch of Gansu Medical Association. [Guidelines for the clinical application of vitamin K in neonates]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2022, Sep 2. 60(9), 877–882. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceratto, S.; Savino, F. Vitamin K deficiency bleeding in an apparently healthy newborn infant: the compelling need for evidence-based recommendation. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, Mar 4. 45(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mihatsch, W.A.; Braegger, C.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Domellöf, M.; Fewtrell, M.; Mis, N.F.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A.; Mlgaard, C.; Embleton, N.; van Goudoever, J.; ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding in Newborn Infants: A Position Paper by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, Jul. 63(1), 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendse, K.; de Meij, T.G.J.; Verheij, J.; Nijmeijer, S.W.R.; Heijboer, H.; Geukers, V.G.M. Het belang van intramusculaire vitamine K-toediening bij pasgeborenen [The importance of administering vitamin K intramuscularly in neonates]. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2021, Jul 26. 165, D5736. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Löwensteyn, Y.N.; Jansen, N.J.G.; van Heerde, M.; Klein, R.H.; Kneyber, M.C.J.; Kuiper, J.W.; Riedijk, M.A.; Verlaat, C.W.M.; Visser, I.H.E.; van Waardenburg, D.A.; van Hasselt, P.M. Increasing the dose of oral vitamin K prophylaxis and its effect on bleeding risk. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019, Jul. 178(7), 1033–1042, Epub 2019 May 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

© 2023 by the author. The materials published in RJMP are protected by copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or purpose. The manuscripts sent to the RJMP become the property of the publication and the authors declare on their own responsibility that the materials sent are original and have not been sent to other publishing houses.