2.1. Theoretical Framework

Most accountants are familiar with modern technology. However, many do not fully utilize these tools to their professional advantage [

2]. By now, accountants should be able to, or may be required to, act as mangers and re-evaluators of accounting systems [

11].

As technology advances, the time required for simpler accounting tasks is reduced [

4]. This time can be used instead to interact with clients and provide entities with information essential for entrepreneurship [

12], as well as to balance one’s professional and personal life and provide meaningful reports and better consulting services and investment opportunities. By prioritizing the most important tasks [

13], artificial intelligence and accounting software saves valuable time by automating basic and complex activities such as data analysis and business consulting [

2].

Advanced Professional Technology: Digitalization is expected to become a cornerstone of strategic importance [

14,

15]. The trend toward implementing intelligent software is crucial in the growth and survival of an entity. Many networking platforms are familiar with big data management and can extract more data and identify potential investors and opportunities [

16]. Knowledge of digitization is a competitive advantage, since it allows reports displaying quantitative data and the interpretation of qualitative characteristics. So far, few academic institutions have developed related curricula, including dominant technologies affecting the accounting industry, such as mobility applications, Cloud technology, and other digital services (including specialized programming languages, big data, electronic payments, cybersecurity, and AI) [

17].

Decision makers’ analytical and practical skills should be used to determine which technology is suitable in each case [

18]. For example, cloud accounting information systems offer the prospect of flexibility and competitive service among their users [

3,

9]. High competition levels, economic development, continuous technological breakthroughs, and increasing demands affect the smooth operation of modern entities. The volume of information and its flow are extremely high, while competition is determined by the ability to manage information [

1,

19]. Based on our literature review, the first research hypothesis was created based on the main elements of technology application and the accounting profession:

H1. Further development and increased application of technology in the accounting industry affects the speed of processing corresponding professional activities.

Risks for Accounting Profession: The strategic success of an organization is a result of the proper design of an accounting information system that supports strategies increasing organizational effectiveness [

20]. To achieve a stronger and more flexible corporate culture in the face of persistent external environmental changes, entities seek and invest in accounting information systems. Innovation is the incentive that can lead to better and consistent performance, reducing financial and organizational barriers [

21]. Technological changes create business opportunities for the accounting industry, as economic entities find it difficult to send quarterly reports and outsource bookkeeping. However, the pressure on accountants due to multiple deadlines and reports becomes more intense throughout the fiscal year. In any case, issues regarding the submission of reports and clearance systems require modern and specialized accounting software. These technologies increase operating costs and place all stakeholders in a constant systemic redesigning cycle [

22]. Certain characteristics such as confidentiality, honesty, interpersonal relationships, critical thinking, reasoning and creativity create strong bonds between accountants and clients and therefore cannot currently be replaced by any information system [

1,

2,

7]. Remote, secure and real-time updatable information systems allow faster client–accountant communication. The direct recording of data in the information system allows for speedy tax advice and strengthened work bonds [

1].

Several accountant roles are expected to disappear [

1]; however, there will still be a need for professional judgment and specialized accounting knowledge to interpret the results of automated processes. The question remains of how to develop advanced judgment and expertise for accountants with shortages of entry-level positions in the future, since these skills are acquired through experience [

23]. Digitization is replacing routine tasks. With the evolution of big data processing algorithms, non-routine tasks are becoming susceptible to automation, especially through the development of artificial intelligence. Consequently, accounting professions with increased critical thinking requirements could face the risk of elimination. Basic accounting processes (payroll, bookkeeping, auditing, and taxation) are very close to becoming completely automated [

22,

24]. Based on this, two hypotheses were formed regarding the main elements of technology and their impact on the accounting profession:

H2. The improvement of the speed and automation of processing accounting professional activities may cause the degeneration of accounting science.

H3. Further development and increased application of technology in the accounting industry may cause the degeneration of accounting science.

Potential for Enhancement of Activities through technology: Digitization has increased online shopping and e-commerce, and nowadays, all kinds of information is being distributed digitally between consumers, businesses, banks, and stakeholders. The majority of accountants believe that digital competence is as important as their knowledge regarding accounting, while 48% of business executives are worried about being left behind, double the number from last year. In developed countries’ tax and customs information system has been upgraded to a new system, under which all business transactions are almost fully automatically and recorded in an electronic tax account, with these accounts then be submitted quarterly for tax clearance [

25].

When it was operational, the UK HMRC IT system was able to monitor and cross-check transactions with tax data, thus eliminating the tax gap that resulted from the manual expansion of incorrect or unrecorded transactions. However, the initial accountability of accountants during the transition to the electronic system was seen as negative, as it replaced much of the way in which processes were carried out. Electronic accounting as an evolution of digital accounting is gaining ground, but it has not yet fully taken its place. Consequently, accountants are now unnecessarily spending money on records to conduct quality checks, when the factor of human error in genetic data has already been eliminated [

12].

Based on the literature review, the two last research hypotheses were created based on the main elements of technology applications and the accounting profession:

H4. The increased speed and automation of processing accounting professional activities improves the supervision procedures of accounting activities and transactions.

H5. The further development and application of technology in the accounting industry improves the supervision procedures of accounting activities and transactions.

2.2. Methodology

During this study, a mixed-methods approach was adopted, which included both qualitative and quantitative methods to increase the reliability and validity of the findings through various tools [

26,

27]. A theoretical model incorporated factors based on the literature and interviews with accounting experts to achieve the appropriate level of expertise and accuracy. Deductive reasoning was adopted to encode the information extracted from the international bibliography. The initial theoretical areas that emerged from the literature were related to accountants’ technological training and familiarization with digitalized accounting applications. Subsequently, our research identified the disadvantages and risks inherent in accounting standardization and information extraction. The third part of the theoretical model concerned the interactive forces and perspectives that digitization provides in accounting operations.

The inductive approach in this research was carried out through semi-structured interviews [

28] with a total of ten interviews, of which two (2) were with Tax Economists—Auditors, three (3) with Certified Public Accountants, three (3) with Accountants—Tax Professionals and two (2) with Accounting and Auditing Professors. Since there were no set limits for the sample size [

29], experts were added “to the point where the additional data collected provided minimal new ideas or evidence”. The questions contained deductive elements, as the questions were mainly formulated based on the review of the international literature and articles but at the same time were orientated toward the specific approach of the accounting profession in Greece, since the country’s tax legislation is complex and prompt to constant changes [

4]. The questions were twelve open-ended questions based on the thematic sections of the literature. From the open-ended questions, closed-ended questions were created and some others that had come from the bibliography were confirmed. All interviews were conducted at scheduled appointments either in person, via video conference (Skype), or by telephone and lasted an average of 30 min each. The interviews took 3 weeks to complete. Thematic analysis [

30] was applied to analyze the information obtained from the interviews.

The above theoretical fields, in combination with the interviews and the literature review, informed the basics of the questionnaire. A thematic analysis was used to analyze the information obtained from the interviews. The experts’ recommendations led to some minor changes in the formulation of the questions and minor verbal changes, while 2 questions were added by the experts regarding time spent on accounting activities, which were considered interesting for further investigation. A pilot survey was conducted in a small sample of eight (8) accountants, via the Internet, preceded by telephone communication, from which the need to reject three questions became apparent, since they were based on local tax and accounting systems and not applicable to larger-scale samples. Specifically, these questions concerned property tax rates, luxury tax (boats, real estate), VAT reductions on islands or tourist areas and constant tax reforms. These taxes are particularly high or fixed in their payment requirements. In some cases, they are applied within the framework of domestic fiscal and environmental strategies, and goes beyond the scope of this research. The final questionnaire consisted of thirty eight (38) Likert-scaled items (response options: “Strongly Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neither Agree nor Disagree,” “Agree,” “Strongly Agree”). The questionnaire included 10 demographic questions that included work experience, educational level, and level of familiarity with information technologies. The target population of this research consisted of 400 accountants, and therefore a sample size of 208 could be considered representative at a 95% confidence level.

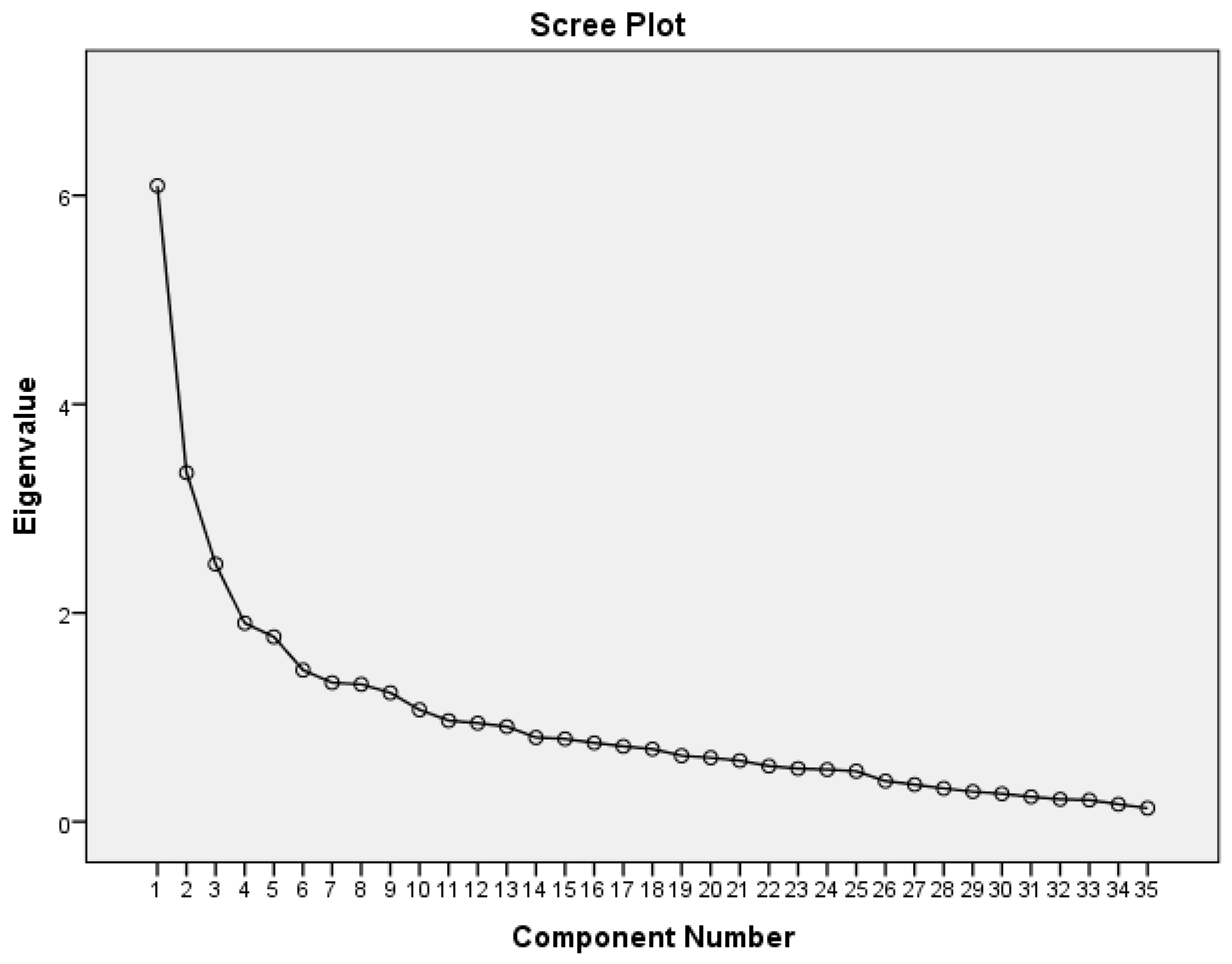

During the control stage of the 210 questionnaires, we observed that 2 of them had more than 50% unanswered questions, and they were removed from the total sample. The construct validity of the variables was determined by conducting Exploratory Factor Analysis. For the extraction method Principal Component Analysis was used and the Varimax rotation technique was adopted, which created factors as independent as possible from each other, so that they can be used in further analysis (hierarchical regression), minimizing the possibility of the presence of collinearity between the variables. As criteria for factor retention a scree plot was used. Rejection limits for factor loadings greater than ±0.40 were set. Finally, the Kaiser rule was applied to decide the number of factors to be extracted, along with the scree test (eigen values). To check the internal consistency reliability of the variables, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was adopted. For the regression analysis a multiple linear regression analysis was used.