Topic Modeling as a Tool to Identify Research Diversity: A Study Across Dental Disciplines

Abstract

1. Introduction

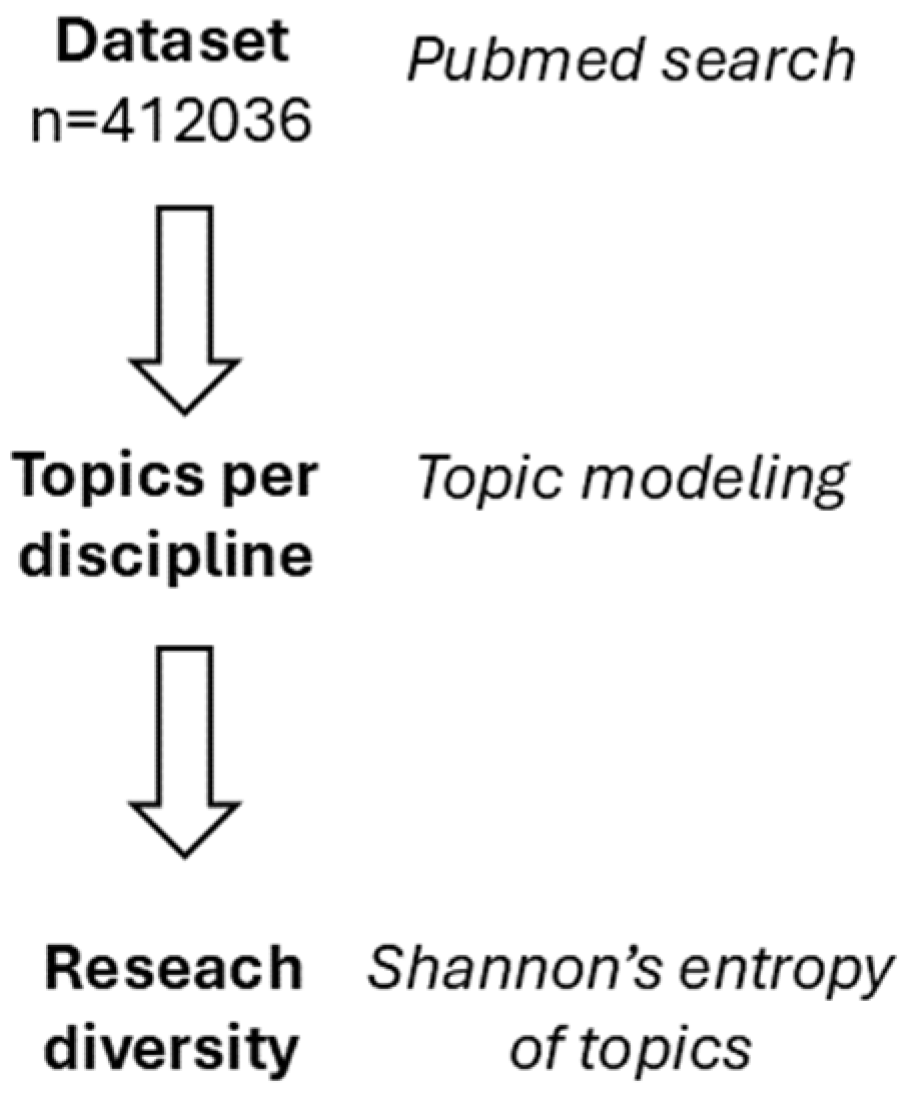

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Cleaning and Preprocessing

- Deduplication: Duplicate entries were identified and removed based on article titles.

- Missing Data: Articles without titles were excluded.

- Standardization: The publication years were standardized to four-digit integers. Articles published before 1994 or after 2023 were excluded from further analysis.

2.3. Topic Modeling

2.3.1. Sentence Embedding and Topic Modeling

2.3.2. Topic Extraction

- -

- UMAP metric: cosine distance;

- -

- Size of the neighborhood: 50;

- -

- Number of components: 5;

- -

- HDBSCAN clustering metric: Euclidean;

- -

- cluster_selection_epsilon = 0.5

- -

- Minimum cluster size: 50.

I have a topic that contains the following documents:

[DOCUMENTS]

The topic is described by the following keywords: [KEYWORDS]

Based on the information above, extract a short but highly descriptive topic label of at most 5 words. Make sure it is in the following format:

topic: <topic label>

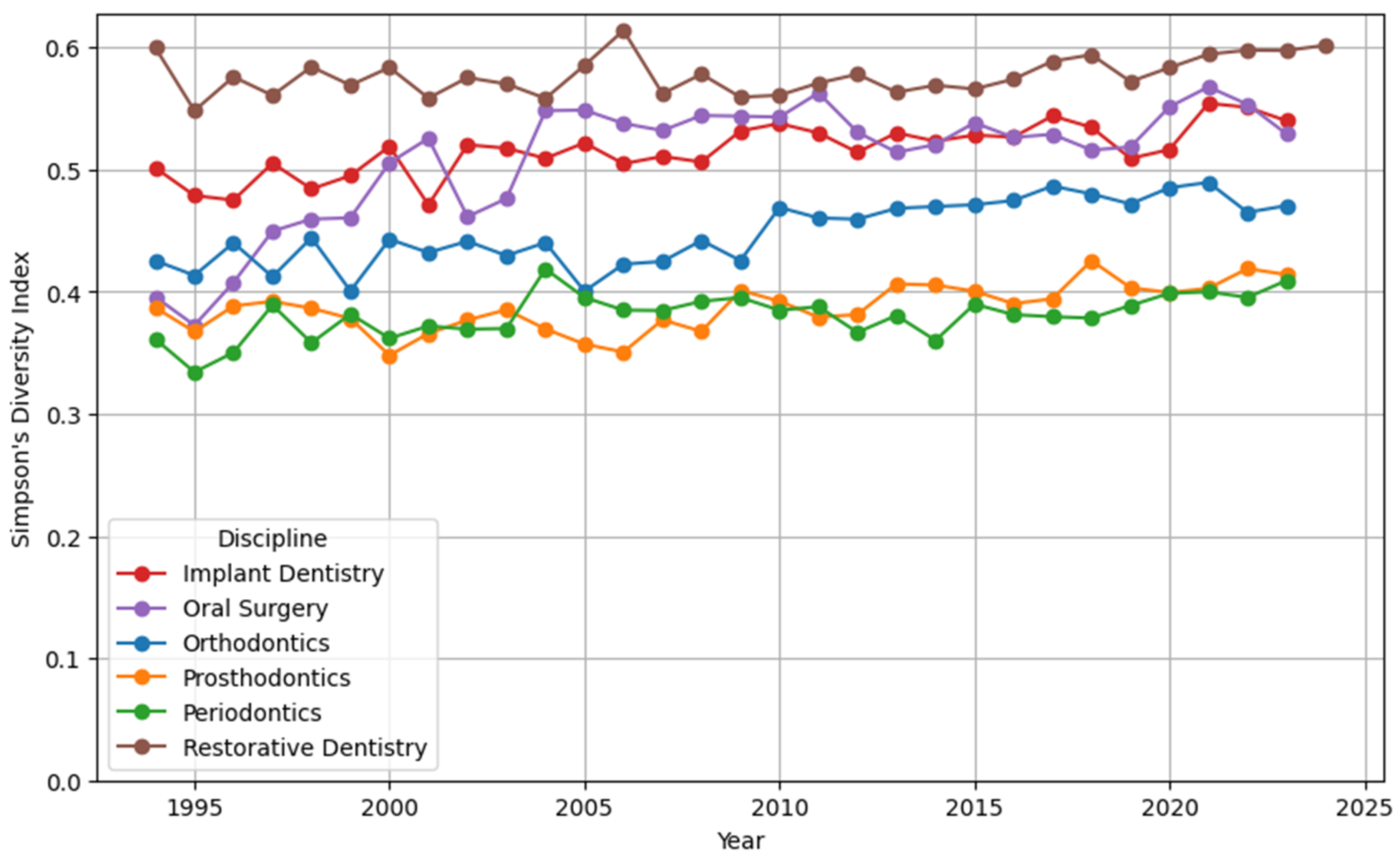

2.4. Entropy Analysis

3. Results

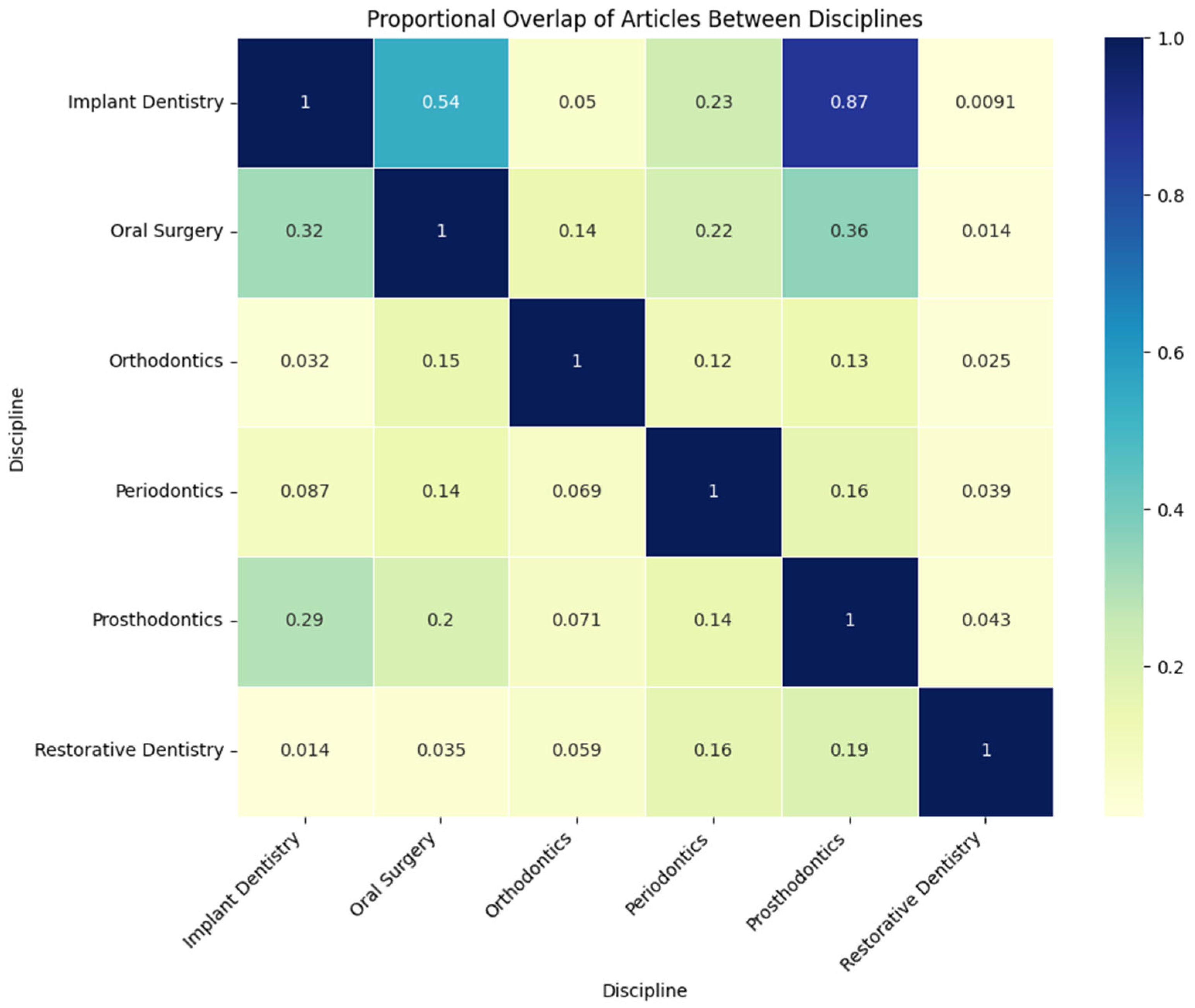

3.1. General Characteristics of the Dataset

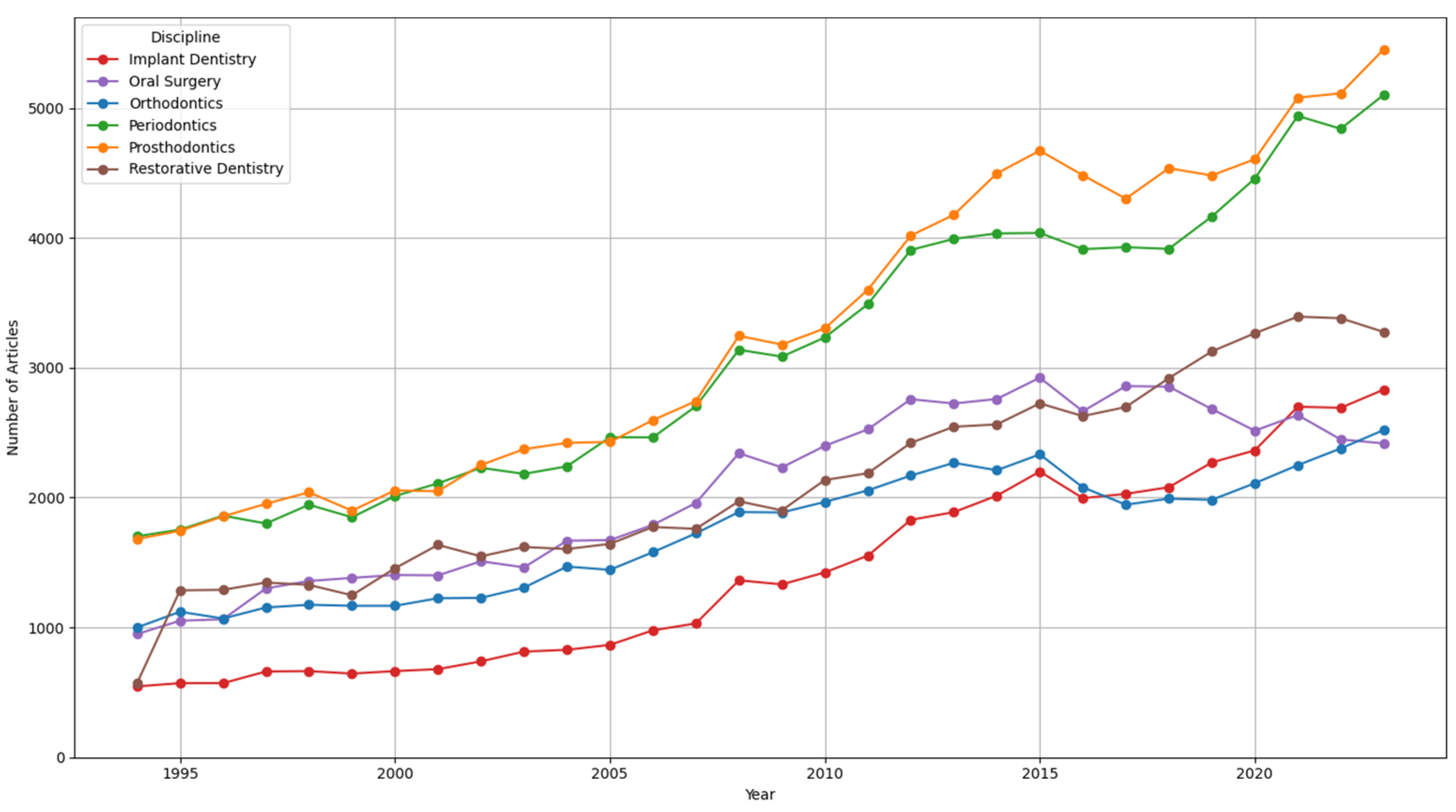

3.2. Distribution of Articles over Time

3.3. Identification of Research Topics

3.4. Diachronic Analysis of Topics

4. Discussion

5. Outlook

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Guo, J.; Gu, D.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhu, K. Tracking Knowledge Evolution, Hotspots and Future Directions of Emerging Technologies in Cancers Research: A Bibliometrics Review. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, S.M.; Reich, J.A. Cultural Competence in Interdisciplinary Collaborations: A Method for Respecting Diversity in Research Partnerships. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 38, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, T.; Tijssen, R. Interdisciplinary Dynamics of Modern Science: Analysis of Cross-Disciplinary Citation Flows. Res. Eval. 2000, 9, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyanes, M.; Demeter, M.; Cheng, Z.; de Zúñiga, H.G. Measuring Publication Diversity among the Most Productive Scholars: How Research Trajectories Differ in Communication, Psychology, and Political Science. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 3661–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y.; Suzuki, J. Promoting Scientodiversity Inspired by Biodiversity. Scientometrics 2017, 113, 1463–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Glaser, J.; Havemann, F.; Heinz, M. A Methodological Study for Measuring the Diversity of Science. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Webometrics, Informetrics and Scientometrics & Seventh COLLNET Meeting, Nancy, France, 10–12 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mantikayan, J.; Abdulgani, M. Factors Affecting Faculty Research Productivity: Conclusions from a Critical Review of the Literature. JPAIR Multidiscip. Res. 2018, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, K.A.; Rubenstein, L.E.; Chesley, F.D.; Eisenberg, J.M. The Roles of Race and Socioeconomic Factors in Health Services Research. Health Serv. Res. 1995, 30, 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Grupp, H. The Concept of Entropy in Scientometrics and Innovation Research. Scientometrics 1990, 18, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godden, J.W.; Bajorath, J. Analysis of Chemical Information Content Using Shannon Entropy. Rev. Comput. Chem. 2007, 23, 263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Mitesser, O.; Heinz, M.; Havemann, F.; Glaser, J.; Gläser, J. Measuring Diversity of Research by Extracting Latent Themes from Bipartite Networks of Papers and References. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Webometrics, Informetrics and Scientometrics & Ninth COLLNET Meeting, Berlin, Germany, 29 July–1 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, J.E.; McLaughlin, G.W.; McLaughlin, J.S.; White, C.Y. Using Simpson’s Diversity Index to Examine Multidimensional Models of Diversity in Health Professions Education. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2016, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havemann, F.; Gläser, J.; Heinz, M.; Struck, A. Identifying Overlapping and Hierarchical Thematic Structures in Networks of Scholarly Papers: A Comparison of Three Approaches. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guizzardi, S.; Colangelo, M.T.; Mirandola, P.; Galli, C. Modeling New Trends in Bone Regeneration, Using the BERTopic Approach. Regen. Med. 2023, 18, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kherwa, P.; Bansal, P. Topic Modeling: A Comprehensive Review. ICST Trans. Scalable Inf. Syst. 2018, 7, 159623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural Topic Modeling with a Class-Based TF-IDF Procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrazek, A.; Eid, Y.; Gawish, E.; Medhat, W.; Hassan, A. Topic Modeling Algorithms and Applications: A Survey. Inf. Syst. 2023, 112, 102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltcov, S.; Ignatenko, V.; Koltsova, O. Estimating Topic Modeling Performance with Sharma–Mittal Entropy. Entropy 2019, 21, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Jose, J.M.; Yu, H.; Moshfeghi, Y.; Triantafillou, P. Topic Detection and Tracking on Heterogeneous Information. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2018, 51, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulgar, R.; Jiménez-Fernández, I.; Jiménez-Contreras, E.; Torres-Salinas, D.; Lucena-Martín, C. Trends in World Dental Research: An Overview of the Last Three Decades Using the Web of Science. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 1773–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, D.; Sennerby, L.; De Bruyn, H. Modern Implant Dentistry Based on Osseointegration: 50 Years of Progress, Current Trends and Open Questions. Periodontol. 2000 2017, 73, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, S. A Primer on Python for Life Science Researchers. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007, 3, e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Maggioni, M.; Smith, J.; Scarpazza, D.P. Dissecting the NVidia Turing T4 GPU via Microbenchmarking. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.07486. [Google Scholar]

- Cock, P.J.A.; Antao, T.; Chang, J.T.; Chapman, B.A.; Cox, C.J.; Dalke, A.; Friedberg, I.; Hamelryck, T.; Kauff, F.; Wilczynski, B. Biopython: Freely Available Python Tools for Computational Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1422–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in Python. SciPy 2010, 445, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, H. Identifying Interdisciplinary Topics and Their Evolution Based on BERTopic. Scientometrics 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-Bert: Sentence Embeddings Using Siamese Bert-Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10084. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. Umap: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Astels, S. Hdbscan: Hierarchical Density Based Clustering. J. Open Source Softw. 2017, 2, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, C.; Donos, N.; Calciolari, E. Performance of 4 Pre-Trained Sentence Transformer Models in the Semantic Query of a Systematic Review Dataset on Peri-Implantitis. Information 2024, 15, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, C.; Cusano, C.; Meleti, M.; Donos, N. Topic Modeling for Faster Literature Screening Using Transformer-Based Embeddings. Metrics 2024, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akre, P.; Malu, R.; Jha, A.; Tekade, Y.; Bisen, W. Sentiment Analysis Using Opinion Mining on Customer Review. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Res. 2023, 13, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gue, C.C.Y.; Rahim, N.D.A.; Rojas-Carabali, W.; Agrawal, R.; Rk, P.; Abisheganaden, J.; Yip, W.F. Evaluating the OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 Turbo’s Performance in Extracting Information from Scientific Articles on Diabetic Retinopathy. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajapeyam, S. Understanding Shannon’s Entropy Metric for Information. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1405.2061. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical Data Visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landhuis, E. Scientific Literature: Information Overload. Nature 2016, 535, 457–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Kaur, M.; Dhillon, J.S.; Mann, J.S.; Kumar, A. Evolution of Restorative Dentistry from Past to Present. Indian J. Dent. Sci. 2017, 9, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Meena, S. Publish or Perish: Where Are We Heading? J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dinesen, P.T.; Schaeffer, M.; Sønderskov, K.M. Ethnic Diversity and Social Trust: A Narrative and Meta-Analytical Review. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2020, 23, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budescu, D.V.; Budescu, M. How to Measure Diversity When You Must. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, R.K. The Measurement of Species Diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1974, 5, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Academic Publishing: Issues and Challenges in the Construction of Knowledge; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, R.; Singh, L. The Evolution of Topic Modeling. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayansky, I.; Kumar, S.A.P. A Review of Topic Modeling Methods. Inf. Syst. 2020, 94, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Yang, T.; Huang, Y.; Yang, B.; Luo, Y.Y.; Richard, L.W.C.; Guo, D. Experimental Comparison of Three Topic Modeling Methods with LDA, Top2Vec and BERTopic. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, Beijing, China, 21–23 October 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 376–391. [Google Scholar]

- Noba, C.; Mello-Moura, A.C.V.; Gimenez, T.; Tedesco, T.K.; Moura-Netto, C. Laser for Bone Healing after Oral Surgery: Systematic Review. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Chuang, S.-K. History of Innovations in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Front. Oral Maxillofac. Med. 2022, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, H.M.; Haq, I.U.; Alrubayan, M.; Alammari, F.; Alotaibi, F.; Al Khammash, A. A Bibliometric Analysis of the Top 100 Cited Articles in Regenerative Periodontics Surgery: Insights and Trends. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2024, 14, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, R.; Leaman, R.; Lu, Z. Accessing Biomedical Literature in the Current Information Landscape. In Biomedical Literature Mining; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Meneghini, R.; Packer, A.L. Is There Science beyond English? EMBO Rep. 2007, 8, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartling, L.; Featherstone, R.; Nuspl, M.; Shave, K.; Dryden, D.M.; Vandermeer, B. Grey Literature in Systematic Reviews: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Contribution of Non-English Reports, Unpublished Studies and Dissertations to the Results of Meta-Analyses in Child-Relevant Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, S.C. Including Papers in Languages Other than English in Systematic Reviews: Important, Feasible, yet Often Omitted. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Discipline | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Implant Dentistry | “Dental Implants” [MeSH] OR “Dental Implantation” [MeSH] OR “Dental Implant” [Title/Abstract] OR “Implant Dentistry” [Title/Abstract] OR “Implantology” [Title/Abstract] |

| Oral Surgery | “Oral Surgical Procedures” [MeSH] OR “Oral Surgery” [Title/Abstract] OR “Oral Surgeons” [Title/Abstract] OR “Maxillofacial Surgery” [Title/Abstract] OR “Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery” [Title/Abstract] |

| Orthodontics | “Orthodontics” [MeSH] OR “Orthodontics” [Title/Abstract] OR “Orthodontic Treatment” [Title/Abstract] OR “Orthodontic Appliances” [MeSH] OR “Orthodontic Brackets” [MeSH]) OR (“Malocclusion” [MeSH] OR “Teeth Misalignment” [Title/Abstract]) |

| Periodontics | “Periodontics” [MeSH] OR “Periodontal” [Title/Abstract] OR “Periodontics” [Title/Abstract] OR “Periodontology” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“Periodontal Diseases” [MeSH] OR “Periodontitis” [MeSH] OR “Gingivitis” [MeSH] OR “Periodontal Pocket” [MeSH] OR “Gum Disease” [Title/Abstract] |

| Prosthodontics | “Dental Prosthesis” [MeSH] OR “dental prostheses” [Title/Abstract] OR “dental prosthesis” [Title/Abstract] OR “Prosthodontics” [MeSH] OR “Prosthodontics” [Title/Abstract] |

| Restorative Dentistry | “Restorative Dentistry” [Title/Abstract] OR “Tooth Filling” [Title/Abstract] OR “Dental Restoration” [Title/Abstract] OR “Restorative Treatments” [Title/Abstract] OR “Dental Caries” [MeSH] OR “Tooth Cavity” [Title/Abstract] OR “Dental Cavities” [Title/Abstract] OR “Tooth Decay” [Title/Abstract] |

| Discipline | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Prosthodontics | 98,852 |

| Periodontics | 93,510 |

| Restorative Dentistry | 63,257 |

| Oral Surgery | 61,719 |

| Orthodontics | 51,872 |

| Implant Dentistry | 42,826 |

| Total | 412,036 |

| Discipline | Number of Topics |

|---|---|

| Restorative Dentistry | 58 |

| Periodontics | 49 |

| Oral Surgery | 34 |

| Prosthodontics | 32 |

| Orthodontics | 32 |

| Implant Dentistry | 22 |

| Discipline | Main Topic |

|---|---|

| Orthodontics | Orthodontic Treatment Evaluation Study |

| Prosthodontics | Dental Implant Clinical Study |

| Periodontics | Periodontal Disease Treatment Studies |

| Implant Dentistry | Dental Implant Management Insights |

| Oral Surgery | Dental Implant Surgical Evaluation |

| Restorative Dentistry | Childhood Caries Prevention Study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Colangelo, M.T.; Guizzardi, S.; Galli, C. Topic Modeling as a Tool to Identify Research Diversity: A Study Across Dental Disciplines. Metrics 2024, 1, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrics1010003

Colangelo MT, Guizzardi S, Galli C. Topic Modeling as a Tool to Identify Research Diversity: A Study Across Dental Disciplines. Metrics. 2024; 1(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrics1010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleColangelo, Maria Teresa, Stefano Guizzardi, and Carlo Galli. 2024. "Topic Modeling as a Tool to Identify Research Diversity: A Study Across Dental Disciplines" Metrics 1, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrics1010003

APA StyleColangelo, M. T., Guizzardi, S., & Galli, C. (2024). Topic Modeling as a Tool to Identify Research Diversity: A Study Across Dental Disciplines. Metrics, 1(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/metrics1010003