Law Reforms and Human–Wildlife Conflicts in the Living Communities in a Depopulating Society: A Case Study of Habituated Bear Management in Contemporary Japan

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

1.2. Legal Responses to Wildlife

2. Legal and Institutional Responses in the United States

2.1. General Responses in the United States

2.2. Responses from California

3. Current Situation of Bears in Japan and the 2024 Legal Amendment

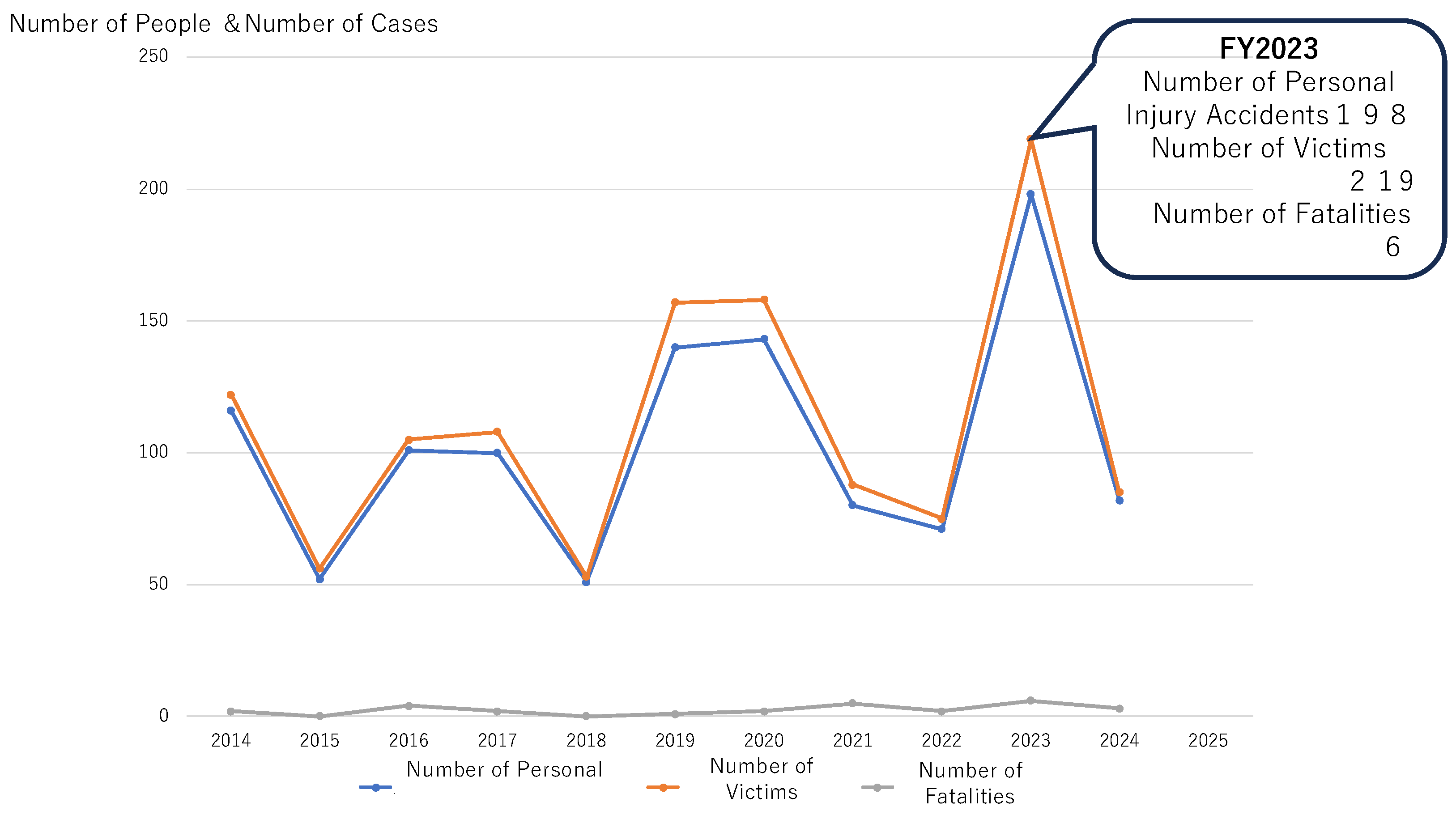

3.1. Increase in Human Casualties Caused by Bears

3.2. Hunting and Authorized Capture

3.3. Securing Hunters and Professional Capturers

4. Bear Appearances in Residential Areas and the 2025 Legal Amendment in Japan

4.1. Before the 2025 Amendment

4.2. The Sunagawa Litigation and Hunters’ Dissatisfaction in Hokkaidō

4.3. The 2025 Amendment

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Japanese Legal Policy

5.2. Limitations and Prospects

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fujitsu Research Institute. Current Situation and Challenges of Regional and Local Areas (Chiiki/Chihō no Genjō to Kadai). (Fujitsu. Sōken). 2019. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000629037.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. Population Estimates as of. (Sōmushō Tōkei-Kyoku). (Suikei, J. Nen 10-Gatsu 1-Nichi Genzai, 2023–). 2023. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2023np/index.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Kondo, K. The Shortage of Bus Drivers and Securing Residents’ Means of Transportation (Basu No Untenshi Busoku Mondai to Jūmin No Ashi No Kakuho). Jūmin to Jichi. 2024. Available online: https://www.jichiken.jp/article/0369/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- United Nations. Department of economic and social affairs. Leveraging population trends for A more sustainable and inclusive future: Insights from world population prospects 2024. Policy Brief 2024, 167, 1–5. Available online: https://social.desa.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/2025-03/PB167.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Academic Block. Geopolitics & International Relation: Balance of Power in a Changing World. 2025. Available online: https://www.academicblock.com (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Lu, M. Ranked: The 20 Countries with the Fastest Declining Populations. Demographics. 2022. Available online: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/ranked-the-20-countries-with-the-fastest-declining-populations/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Cafaro, P.; Hansson, P.; Götmark, F. Overpopulation is a major cause of biodiversity loss and smaller human populations are necessary to preserve what is left. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 272, 109646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, T. The Great Abandonment: What Happens to the Natural World When People Disappear? The Guardian. 28 November 2024. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2024/nov/28/great-abandonment-what-happens-natural-world-people-disappear-bulgaria (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Kaplan, B.S.; O’Riain, M.J.; van Eeden, R.; King, A.J. A low-cost manipulation of food resources reduces spatial overlap between baboons (Papio ursinus) and humans in conflict. Int. J. Primatol. 2011, 32, 1397–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Fund for Animal Welfare (I.F.F.W.). Human-Wildlife Conflict in Kenya. 2024. Available online: https://www.ifaw.org/journal/human-wildlife-conflict-kenya (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Smith, T.S.; Herrero, S.; DeBruyn, T.D. Alaskan brown bears, humans, and habituation. Ursus 2005, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. Why Are Urban Bears Increasing? The Ecology of Bears Influenced by Human Society: Man-eating Incidents at Lake Shumarinai and Mt. Daissenken, and the Shock of OSO18 (Naze āban bea ga fuete iru no ka: Ningen shakai ni sayūsareru kuma no seitai: Shumarinai kohan to Daissenkendake de no hitokui, OSO18 no shōgeki). Chuo-Koron, February 2024; pp. 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kohsaka, R.; Kohyama, S. State of the art review on land-use policy: Changes in forests, agricultural lands and renewable energy of Japan. Land 2022, 11, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M. Current status and issues of hunting: Mismatch between ‘capture system’ and ‘license system’. In Light of General Discussions on Licensing Systems and Concepts (Shuryō no Genjō to Kadai “Hokaku Seido” to “Menkyo Seido” no Misumatchi—Menkyo no Sho Seido ya Kangaekata ni Kankawaru Ippanron ni Terashite—); Committee of the Science Council of Japan on the Management of Wildlife in a Population-Declining Society (Nihon Gakujutsu Kaigi Jinkō Shukushō Shakai ni okeru Yasei Dōbutsu Kanri no Arikata no Kentō ni Kansuru Iinkai): Tokyo, Japan, 2018; Slides 1–12; Available online: https://www.scj.go.jp/ja/member/iinkai/yaseidobutu/pdf/shiryo2403-4-1.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Pop, M.I.; Iosif, R.; Promberger-Fürpass, B.; Chiriac, S.; Keresztesi, Á.; Rozylowicz, L.; Popescu, V.D. Romanian brown bear management regresses. Science 2025, 387, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Slovak Government Cull of 350 Brown Bears. 2025. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-10-2025-001897_EN.html (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Beckmann, J.P.; Karasin, L.; Costello, C.; Matthews, S.; Smith, Z. Coexisting with black bears: Perspectives from four case studies across North America. In Working Paper No. 33; Wildlife Conservation Society: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 33–78. Available online: https://www.arlis.org/docs/vol1/A/227208281.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Lackey, C.W.; Breck, S.W.; Wakeling, B.F.; White, B. Human-Black Bear Conflicts: A review of common management practices. Hum.-Widlife Interact. Monogr. 2018, 2, 1–68. Available online: https://www.fishwildlife.org/application/files/6116/1297/7054/Human-Black_Bear_Conflicts__A_Review_of_Common_Management_Practices.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Bombieri, G.; Naves, J.; Penteriani, V.; Selva, N.; Fernández-Gil, A.; López-Bao, J.V.; Ambarli, H.; Bautista, C.; Bespalova, T.; Bobrov, V.; et al. Brown bear attacks on humans: A worldwide perspective. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch-Mordo, S.; Wilson, K.R.; Lewis, D.L.; Broderick, J.; Mao, J.S.; Breck, S.W. Stochasticity in natural forage production affects use of urban areas by black bears: Implications to management of human-bear conflicts. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpoca, A.; Voiculescu, M. Patterns of human-brown bear conflict in the urban area of Brașov, Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzo-Arias, A.; Delgado, M.M.; Ordiz, A.; García Díaz, J.; Cañedo, D.; González, M.A.; Romo, C.; Vázquez García, P.; Bombieri, G.; Bettega, C.; et al. Brown bear behaviour in human-modified landscapes: The case of the endangered Cantabrian population, NW Spain. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 16, e00499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.Y.; Amano, T.; Akasaka, M.; Koike, S. The range of large terrestrial mammals has expanded into human-dominated landscapes in Japan. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunoda, H.; Enari, H. A strategy for wildlife management in depopulating rural areas of Japan. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, J. Evolution: Mammals of Japan (Shinka: Nihon no honyūrui). In Mammalogy; Koike, S., Sato, J., Sasaki, M., Enari, H., Eds.; University of Tokyo Press (Tōkyō Daigaku Shuppan): Tokyo, Japan, 2022; pp. 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment. Explanation of the Act on Protection and Management of Wildlife (Chōjū Hogo Kanrihō no Kaisetsu) (Kaitei 5 Han), 5th revised ed.; Wildlife Division, Nature Conservation Bureau, Wildlife Protection and Management Office (Shizen Kankyōkyoku Yasei Seibutsuka Chōjū Hogo Kanrishitsu), Ed.; Taisei Shuppansha: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment. Japan. Strengthening Wildlife Management: Designated Wildlife Control Project (Chōju no Kanri no Kyōka: Shitei Kanri Chōju Hokaku tō Jigyō). 2024. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/reinforce/index.html (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Kai, I. Brown and Black Bears Added to ‘Controlled Animals’ List. Asahi Shimbun Azia and Japan Watch. (English). 2024. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15232300 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Xinhua. Bears Designated as Animal Subject to Subsidized Culling in Japan. South Asian Network TV. 2024. Available online: https://en.sicomedia.com/2024/0417/36165.shtml (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Uwabo, K. Veteran Hunter Loses Reversal Appeal, Firearm License Revoked Over Bear Culling—Sapporo High Court (Beteran Ryōshi ga Gyakuten Haiso, Higuma Kujo de jū no Kyoka Torikesare Sapporo Kōsai). Asahi Newspaper. 2024. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASSBL324PSBLIIPE003M.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. Japan. Various Initiatives on Protection and Management: Emergency Shooting System (Hogo Oyobi Kanri ni Kakawaru Samazama na Torikumi: Kinkyū Jūryō Seido). 2025. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/effort/effort15/effort15.html (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Kyodo News (English). Japan Enacts Emergency Animal Shooting Law amid Surge in Bear Attacks. 2025. Available online: https://english.kyodonews.net/articles/-/53379 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- South China Morning Post (English). Japan Makes it Easier for Hunters to Shoot Bears as Attacks Surge: The Revised Wildlife Law Allows Emergency Bear Shootings in Populated Areas, Enabling Quicker Responses Amid Rising Animal Sightings. 2025. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/east-asia/article/3307028/japan-makes-it-easier-hunters-shoot-bears-attacks-surge (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- The Wildlife Society. Certification Programs. Available online: https://wildlife.org/certification-programs/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Miller, J.E. Evolution of the field of wildlife damage management in the United States and future challenges. Hum. Wildl. Confl. 2007, 1, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- U.S.D.A. APHIS-Wildlife Services. Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment for Wildlife Damage Management Methods: The Use of Dogs and Other Animals in Wildlife Damage Management. Peer Reviewed Final. 2017. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/15-dog-use.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- European Commission. Large carnivore initiative for Europe. In Guidelines for Population Level Management Plans for Large Carnivores (FINAL Version); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680746791 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Milla Niemi, M.; Matala, J.; Melin, M.; Eronen, V.; Järvenpää, H. Traffic mortality of four ungulate species in southern Finland. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 11, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Zedrosser, A.; Kojola, I.; Swenson, J.E. The management of brown bears in Sweden, Norway and Finland. In Bear and Human: Facets of a Multi-Layered Relationship from Past to Recent Times, with Emphasis on Northern Europe; Grimm, O., Ed.; Brepols Publishers: Turnhout, Belgium, 2023; Volume 3, pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Bear Safety. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/bear-safety (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Human-Polar Bear Conflict Management. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/project/human-polar-bear-conflict-management (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Spencer, R.D.; Beausoleil, R.A.; Martorello, D.A. How agencies respond to human–black bear conflicts: A survey of wildlife agencies in North America. Ursus 2007, 18, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don Carlos, A.W.; Bright, A.D.; Teel, T.L.; Vaske, J.J. Human–black bear conflict in urban areas: An integrated approach to management response. Hum. Dimen. Wildl. 2009, 14, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belant, J.L.; Simek, S.L.; West, B.C. (Eds.) Managing Human-Black Bear Conflicts; Human-Wildlife Conflicts Monograph Number 1; The Center for Human-Wildlife Conflict Resolution, Mississippi State University: Starkville, MI, USA; pp. 1–77. Available online: https://www.humanwildlifeconflicts.msstate.edu/docs/Black%20bear%20Final%2012-7-11.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- I.U.C.N.-Species Survival Commission (SSC). The IUCN SSC Guidelines on Human-Wildlife Conflict and Coexistence. 2023. Available online: https://www.hwctf.org/guidelines (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Be Bear Wise. Available online: https://dec.ny.gov/nature/animals-fish-plants/black-bear/management/bearwise (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Endangered Species Permits: Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: http://www.fws.gov/page/endangered-species-permits-frequently-asked-questions (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- City of Boulder. Ordinance No. 7962: An Ordinance Amending Chapter 6-3, “Trash, Recyclables and Compostables,” B.R.C. 1981, by Adding a New Section 6-3-12 Requiring Bear-Resistant Containers in a Designated Area of the City. 2014. Available online: https://documents.bouldercolorado.gov/weblink8/0/doc/125003/Page1.aspx (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- State of Wyoming -Town of Jackson. Ordinance No. 1323: An Ordinance Adding Sections 8.12.105 and 8.12.108 to the Municipal Code of the Town of Jackson Relating to Bear-Resistant Containers and Providing for an Effective Date. 2022. Available online: https://jhwildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Town_of_Jackson_Ordinance.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- California Legislative Information. Fish and Game Code—FGC. Available online: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codesTOCSelected.xhtml?tocCode=FGC (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- California State-Department of Fish and Wildlife Staff. Black Bear Policy in California: Public Safety, Depredation, Conflict, and Animal Welfare; California State-Department of Fish and Wildlife Staff: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=198982&inline (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Justia regulations, California Code of Regulations, Title 14—Natural Resources, Division 1, Subdivision 2, Chapter 4—Depredation. Available online: https://regulations.justia.com/states/california/title-14/division-1/subdivision-2/chapter-4/section-401/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- California State-Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). Black Bear Policy in California: Public Safety, Depredation, Conflict and Animal Welfare. Departmental Bulletin No. 2022-01, 16 February 2022. Available online: https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=198982&inline=1 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- California State-Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). Human-Black Bear (Family Unit) Conflict Response Guidelines. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/natural-resource-policy-legislation/fish-and-wildlife-policy/response_guidelines_black_bear_family_unit.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Dheer, A.; Furnas, B. Black Bear Conservation and Management Plan for California; Department of Fish and Wildlife (California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW)): Sacramento, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- City of Colorado Springs. Bear Management and Resistant Trash Ordinance. Available online: https://coloradosprings.gov/bears (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Wernick, J. DEC Issues Guidance to Reduce Conflicts with Bears: Public Encouraged to Remove Bird Feeders, Food Pets Indoors; New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (D.E.C.). 2023. Available online: https://dec.ny.gov/news/press-releases/2023/4/dec-issues-guidance-to-reduce-conflicts-with-bears (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- 36 CFR § 2.10(d)—Camping and Food Storage. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-36/part-2/section-2.10 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- State-Fish, C.; Game Commission. Mammal Hunting Regulations: General Provisions and Definitions. Available online: https://fgc.ca.gov/Regulations/Current/Mammals/General-Provisions-and-Definitions (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Kimberlee, S. Mother Bear with ‘Long History of Human Conflict’ Euthanized After Attacking Camper, Sending Her to the Hospital. People. 28 June 2025. Available online: https://people.com/mother-bear-with-long-history-of-human-conflict-euthanized-after-attacking-camper-11763190 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Johnson, H.E.; Lewis, D.L.; Verzuh, T.L.; Wallace, C.F.; Much, R.M.; Willmarth, L.K.; Breck, S.W. Human development and climate affect hibernation in a large carnivore with implications for human–carnivore conflicts. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Sawaya, A.; Igarashi, M.; Gayman, J.J.; Dixit, R. Strained agricultural farming under the stress of youths’ career selection tendencies: A case study from Hokkaido (Japan). Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilley, L.; Gkartzios, M.; Kudo, S.; Odagiri, T. Hybridising counterurbanisation: Lessons from Japan’s kankeijinkō. Habitat. Int. 2024, 143, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population Strategy Council (Jinkō Senryaku Kaigi). Local Government “Sustainability” Analysis Report: Actual Conditions and Issues of Municipalities Based on New Regional Future Population Estimates (Jinkō Senryaku Kaigi. 2024 (Reiwa 6) Nen: Chihō Jichitai “Jizokukanōsei” Bunseki Repōto: Aratana Chiikibetsu Shōrai Suitei Jinkō Kara Wakaru Jichitai no Jijō to Kadai). 2024. Available online: https://www.hit-north.or.jp/cms/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/01_report-1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Asahi Newspaper. “Potentially Disappearing Municipalities” Map and List. (Shimbun, A. Shōmetsu Kanōsei Jichitai Mappu to Ichiran 2024). 2024. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/special/population2024/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. Various Measures Related to Protection and Management: Information and Initiatives on Bears (Hogo Oyobi Kanri ni Kakaru Samazama na Torikumi: Kuma ni Kansuru Kakushu Jōhō/Torikumi). 2025. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/effort/effort12/effort12.html (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. Number of Bear-Related Human Injury Cases in FY2023 (Reiwa 5) (2023 (Reiwa 5) Nendo ni Okeru Kuma no Jinshin Higai Kensū. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/effort/effort12/r05injury-qe.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- TV-Asahi News. Seven People Have Been Killed by Bears, Surpassing the Record High of Fiscal Year 2023, as Bear-Related Incidents Continue to Occur Across The Country (Kuma ni Yoru Giseisha Shichinin ni, Kako Saita no Nisen-Nijūsan-Nendo o Koeru, Zenkoku Kakuchi de Higai Aizugu). 2025. Available online: https://news.tv-asahi.co.jp/news_society/articles/000460024.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kurisu, S. Comprehensive Bear Map: Created a Link Page to Nationwide Bear (Kuma) Sighting Information Maps! (Shigeyuki. Kuma Mappu Sōgōban: Zenkoku no Kuma Shutsugen Jōhō Mappu no Rinku Pēji o Tsukutte Mita!). Japan News; Yahoo! 24 May 2024. Available online: https://news.yahoo.co.jp/expert/articles/90109037132739f241f40cfa2a124fce4470cc8f (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. Capture of Wild Birds and Mammals: Overview of the Capture Permit System (Yasei Chōjū no Hokaku: Hokaku Kyoka Seido no Gaiyō). Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/capture/capture1.html (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Knight, C. The system of wildlife management and conservation in Japan, with particular reference to the Asiatic black bear. N. Z. J. Asian Stud. 2007, 9, 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Kaji, K. Experience of the prefecture with hunting management influences the effectiveness of wildlife policy. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Takahashi, K.; Washitani, I. Do small canopy gaps created by Japanese black bears facilitate fruiting of fleshy-fruited plants? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Kohno, N.; Mano, S.; Fukumoto, Y.; Tanabe, H.; Hasegawa, M.; Yonezawa, T. Phylogeographic and demographic analysis of the Asian Black bear (Ursus thibetanus) based on mitochondrial DNA. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Y.; Osada, N.; Mano, T.; Masuda, R. Demographic history of the brown bear (Ursus arctos) on Hokkaido island, Japan, based on whole-genomic sequence analysis. Genome Biol. Evol. 2021, 13, evab195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIyabata, Y. After Bear Culling: ‘Tax Thieves,’ ‘Quit the Town Hall’—Mass Complaints Disrupt Operations. Will the ‘Request for Understanding’ Be Heard? (Kuma Kujō Shitara “Zeikin Dorobō” “Yakuba o Yamero” Ōryō Kurēmu de Gyōmu ni Shishō “Go-rikai no Onegai” wa Todoku no ka?). Tokyo-Shimbun (Tokyo Newspaper), 5 November 2023. Available online: https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/288046 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Hokkaido Bunka Broadcasting. Flood of Complaints over Bear Culling: ‘Why Did You Kill Them?’ ‘World Natural Heritage should Be Returned,’ ‘No Need to Kill Cubs’—Long Calls and Emails over the Culling of Three Bears Involved in an Attack at Mt. Rausudake (Kuma Kujō ni Kujō Sattō: “Naze Koroshitan da” “Sekai Shizen Isan o Henkan Subeki” “Koguma wa Korosu Hitsuyō ga Nai n ja nai ka” … Rausudake de Dansei Shūgeki shita Oyako Kuma 3 Tō no Kujō Meguri Machi ni Kujō). Hokkaido News. 19 August 2025. Available online: https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/69c5a44e49dfcc463827a55b8769999a978d2c55 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Tokyo-Shimbun (Tokyo Newspaper). Image from Hokkaido Government Website Appealing for Understanding of Brown Bear Culling (Higuma (Brown Bear) no Kujō e no Rikai o Motomeru Hokkaidō-chō no Yobikake Website Gazō). 5 November 2023. Available online: https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article_photo/list?article_id=288046&pid=1230299 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Manabe, A. The Outcry of ‘Don’t Kill the Bears!’ and ‘How Pitiful!’ Following Brown Bear Incidents in Hokkaido Reveals a Moral Reaction of Ten Expressed by Those Distant from the Risk Zone.(“Kuma o Korosu na!” “Kawaisō da!”…Hokkaidō de Higuma ni Yoru Jiken ga Hassei → Kujyo mo Kurēmu Satsutō. Anzenken no Enpō Kara Kurēmu o Ireru Hitobito no Shinri to wa?) Toyo-Keizai. 2025. Available online: https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/895692 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ikuta, C. The Number of People Holding Hunting Licenses Is Increasing, but Few Actually Go Hunting—Support Programs Are also Being Developed for So-Called ‘Paper Hunters.’ (Fueru “Shuryō Menkyo” Shoyūsha, Jissai ni ryō ni deru hito wa Sukunaku…“Pēpā Hantā” Muke Shien mo). Yomiuri Newspaper. 2025. Available online: http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/national/20250411-OYT1T50066/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Suzuki, M. The Narrative Progression of Fostering Public and Professional Wildlife Capturers: Introduction, Development, Turning Point, and Conclusion (Kōkyōteki/Senmonteki Hokaku no Ninaite Ikusei o Meguru Kishōtenketsu); Wildlife Forum: Association of Wildlife and Human Society: Tokyo, Japan, 2023; Volume 28, pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Board of Audit of Japan (Kaikei Kensain). On the Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Comprehensive Wildlife Damage Prevention Support Programs (Chōjū Higai Bōshi Sōgō Shien Jigyō-tō ni okeru Hiyō Tai Kōka Bunseki ni tsuite) Fiscal Year 2012 Accounting Report. Available online: https://report.jbaudit.go.jp/org/h25/2013-h25-0507-0.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Board of Audit of Japan (Kaikei Kensain). In Implementing the Comprehensive Wildlife Damage Prevention Measures, the Board Required Improvements by Instructing Project Operators, Municipalities, and Prefectural Governments to Clearly Present to Project Operators and Municipalities the Methods for Surveying and Calculating the Actual Damaged Areas and Monetary Losses, and to Thoroughly Verify Whether Such Surveys and Calculations Are Appropriate. Furthermore, in Cases Where the Achievement Status of Reduction Targets for Certain Wildlife Species Causing Significant Damage Is Low, the Board Required That Project Operators and Municipalities Be Informed to Develop Improvement Plans and Other Necessary Measures So That the Monitoring of Reduction Target Achievement and the Preparation of Improvement Plans Can Be Carried Out Appropriately. (Chōjū Higai Bōshi Sōgō Shien Taisaku no Jisshi ni Atari, Jisshigai Menseki Oyobi Jisshigai Kingaku no Chōsa oyobi Sanshutsu no Hōhō o Jigyō Shutai Oyobi Shichōson ni Taishite Wakariyasuku Shimeshi, Tōgai Chōsa Oyobi Sanshutsu ga Tekisetsuna Mono to Natte iru ka Jūbun ni Kakunin suru yō jigyō Shutai, Shichōson Oyobi Todōfuken ni Taishite Shidō Suru to Tomoni, Ōkina Higai o Oyoboshite iru Chōjū ni Tsuite Taishō Chōjū goto ni miru to Keigen Mokuhyō no Tassei Jōkyō ga Teichōna mono ga aru baai nado ni wa, Kaizen Keikaku no Sakusei nado o Okonau yō Jigyō Shutai Oyobi Shichōson ni Taishite Shūchi suru koto ni yori, Keigen Mokuhyō no Tassei Jōkyō no Haaku Oyobi Kaizen Keikaku no Sakusei nado ga Tekisetsu ni Okonawareru yō Kaizen no Shochi o Yōkyū Shita Mono). 22 October 2024. Available online: https://report.jbaudit.go.jp/org/r05/2023-r05-0304-0.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kohyama, S. Key points of the act on the prevention of damage caused by wildlife (Chōjū ni yoru Higai Bōshi ni kansuru Hōritsu no Pointo). Jichitai Hōmu Kenkyū 2024, 77, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Chairpersons of City Councils-Shikoku Chapter. On the Revision of the Subsidy System and Financial Measures Related to Nuisance Wildlife Control ProjectsYūgai Chōjū Taisaku Jigyō ni kakaru Hojo Seido no Minaoshi to Zaigen Sochi ni Tsuite. (Gichōkai-Shikoku, Z.S. Bukai). 2023. Available online: https://www.si-gichokai.jp/request/request-naccc/r06/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2024/11/07/14.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Japan Hunters’ Association. The Path to Becoming a Hunter-Social Contributions Through Hunting (“Shuryōsha e no Michi” —Shuryō ni yoru Shakai Kōken). (Dai-Nippon Ryōyūkai). Available online: http://j-hunters.com/tobecome/contribution.php (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kohyama, S. Learning Environmental Law (Shizen Kankyōhō o Manabu); Bunshindō: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- National Police Agency. On the application of article 4. Paragraph 1 of the Police Duties Execution Act in Responding to Cases Where Bears and Other Animals Appear in Residential Areas and Endanger Human Life or Body” (Notification No. 43 of the Police Affairs Bureau and No. 153 of the Planning Bureau) (Kuma-tō ga Jūtaku-gai ni Araware, Hito no Seimei/Shintai ni Kiken ga Shōjita Baai no Taiō ni okeru Keisatsukan Shokumu Shikkōhō Dai 4-jō Dai 1-kō no Tekiyō ni Tsuite’ Chōhohatsu Dai 43-gō oyobi Keisatsuchō Chō Kikaku-hatsu Dai 153-gō) 2023. Tokyo, Japan. Available online: https://www.npa.go.jp/laws/notification/seian/hoan/hoan20230328-1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- National Police Agency (Keisatsuchō). Directive No. 188; on the Application of Article 4. Paragraph 1 of the Police Duties Execution Act in Cases Where Bears or Other Wild Animals Appear in Residential Areas- Notification (Keisatsuchō Chōhohatsu Dai 188-gō; Kuma nado ga Jūtaku-gai ni Shutsubotsu Shita Baai ni Okeru Keisatsukan Shokumu Shikkō-hō Dai 4-jō Dai 1-kō o Tekiyō Shita Taiō ni Tsuite [Tsuchi]). 2020. Available online: https://knowledge.nilay.jp/static/6cc25ad3c3a083d33ad1257220ad9a51/b616cf2d-496d-46de-a54d-4f01bc88efa1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Editoral Board of Hanrei Times (Hanrei Taimuzu). Sapporo District Court (17 December 2021). Hanrei Times (Hanrei Taimuzu) 2022, 1495, 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kohyama, S. Case Study: Cases in which hunters involved in extermination of beasts were allowed to revoke their rifle possession permits (Sapporo District Court, 17 December 2021, Hanrei Taimuzu 1495, 158). Tomidai-Keizai-Ronshū 2022, 68, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, Y. A Case in Which the Revocation of a Firearm Possession Permit Under Article 11. Paragraph 2022, 1, Item 1 of the Firearms and Swords Control Act Was Overturned (Jūtō-hō Jūichi-jō Ikkō Ichigō ni motodzuku Jūhō Shoji Kyoka Torikeshi Shobun ga Torikesareta Jirei). Shin-Hanrei Kaisetsu Watch 2022, 31, 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara, Y. Case in Which Revocation of Firearm Possession Permit Under Article 11. Paragraph 2025, 1, Item 1 of the Act for Firearms and Swords Was Not Considered an Abuse of Discretion (Jūtōhō Act for Firearms and Swords 11-jō 1-kō 1-gō ni Motoduku Jūhō Shoji Kyoka Torikeshi Shobun ga Sairyōken no Itsudatsu/Ranyō ni Ataranai to Sareta Jirei). Shin-Hanrei Kaisetsu Watch 2025, 36, 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bengo4.com (Bengoshi Dot Com). ‘Adverse Impact on Bear Culling’: Hunter Loses on Appeal in Firearm Lawsuit — Plaintiff Takes the Case to the Supreme Court, Now Working ‘Unarmed’ in the Field (‘Higuma Kujyo ni Aku Eikyō’: Ryōjū Soshō, Nishin de Gyakuten Haisō… Gengoku Hunter wa Jōkoku, Ima wa ‘Marugoshi’ de Genba ni). 2 November 2024. Available online: https://www.bengo4.com/c_1017/n_18095/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Japan Times. Firearm Permit Ruling Casts Shadow over Work of Hokkaido Bear Hunters. 2024. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2024/12/09/japan/crime-legal/hokkaido-bear-hunters/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. Outline of the Bill Partially Amending the Act on the Protection and Management of Wildlife, and the Optimization of Hunting (Chōjū no Hogo oyobi Kanri narabini Shuryō no Tekiseika ni kansuru Hōritsu no Ichibu o Kaisei suru Hōritsu-an no Gaiyō: English Version), 2025. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/content/000297714.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. Outline of the Bill Partially Amending the Act on the Protection and Management of Wildlife, and the Optimization of Hunting, English version; Ministry of the Environment: Tokyo, Japan, 2025; Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/outline/172/905R711.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Wildlife Protection and Management Office; Wildlife Division; Nature Conservation Bureau; Ministry of the Environment (Kankyōshō Shizen Kankyōkyoku Yasei Seibutsu-ka Chōjū Hogo Kanri Shitsu). Emergency Shooting Guideline (Kinkyū Jūryō Gaidorain). 8 July 2025. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/effort/effort15/doc/guideline.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. WPMA Amendment Bill; Draft Amendment to the Act on the Protection and Management of Wildlife and the Proper Regulation of Hunting; Old and New Targets (WPMA Kaiseian; Chōjū no Hogo oyobi Kanri narabi ni Shuryō no Tekiseikan ni Kansuru Hōritsu no Kaiseian; Shinkyū Taishō). Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/content/000297717.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- National Police Agency. About Partially Amending the Act on the Protection and Management of Wildlife, and the Optimization of Hunting (Notification No. 171 of the Police Affairs Bureau) (Chōjū no Hogo Oyobi Kanri Narabini Shuryō no Tekiseika ni Kansuru Hōritsu no Ichibu Kaisei ni Tsuite (Tsūtatsu)). 2025. Available online: https://www.npa.go.jp/laws/notification/seian/hoan/R070822tyojuhogokaisei.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Katano, H. Even If Bears Appear, Hunters May Refuse to Fire: Hokkaido Hunting Association Sends Bitter Notice to Branches (Kuma Shutsubotsu Shitemo Happō Kyohi OK Hokkaidō Ryōyūkai ga Shibu ni Kujū no Tsūchi e). Mainichi Newspaper. 2025. Available online: https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/0c709b44188bfe9c6233f90f47ac89150a49ab47 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- The Asahi Shimbun. Bear Appears in Sendai City-First in the Nation to Be Culled Under ‘Emergency Firearms Hunting’; City States It Was ‘Properly Executed’ (Sendai-Shinai ni Kuma Shutsubotsu, Zenkoku Hatsu no “Kinkyū Jūryō” de Kujyo, shi “Tekisetsu ni Jisshi”). 2025. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASTBH3J85TBHUNHB00PM.html?msockid=05bb347d605860902150222b619661f4 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. Status of Emergency Shooting Implementation: As of 4:30 p.m., October 31, 2025, Limited to the Cases Identified by the Ministry of the Environment. The Figures Presented Herein Shall Be Regarded as the Ministry’s Latest Official View as of the Date of Publication on Its Website. (Kinkyū Jūryō no Jisshi Jōkyō Reiwa 7-nen 10-Gatsu 31-Nichi 16-ji 30-fun Genzai, Kankyō-shō ga Haaku Suru Jirei ni Kagiru.Hon Shiryō no Kankyō-shō HP Keisai o Motte Saishin no Kensū ni Kakaru Kenkai to Suru). Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/effort/effort12/kinkyu-jishi.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Nippon, T.V. Network. News (KNB). Explanation: What Is Emergency Firearms Hunting, and Who Decides How It’s Carried Out? “If the Person Giving the Order Is an Amateur”…”-Confusion Among Members of the Hunters’ Association (Kaisetsu: Kinkyū Jūryō to wa, dare ga dō Handan Suru?”Shiji Suru Mono ga Shirōto da to…” Ryōyūkai ni wa Konwaku mo). 16 October 2025. Available online: https://news.ntv.co.jp/category/society/knf76ea0850ee844c083ab4f82a59cef98 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Science Council of Japan. Response: The management of wildlife in a population-declining society (Jinkō Shukushō Shakai ni okeru Yasei Dōbutsu Kanri no Arikata). Nihon Gakujutsu Kaigi 2019, 11, 1–47. Available online: https://www.scj.go.jp/ja/info/kohyo/pdf/kohyo-24-k280.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Wakayama World Heritage Center. Understanding World Heritage: The Three Grand Shrines of Kumano (Sekai Isan o Shiru: Kumano Sanzan). Available online: https://www.sekaiisan-wakayama.jp/know/kumano-sanzan/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Official Website of Musashi Mitake Shrine (Musashi Mitake Jinja Kōshiki Saito). Available online: http://musashimitakejinja.jp/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Clulow, A. The pirate returns: Historical models, East Asia and the war against Somali piracy. Asia Pac. J. Jpn. Focus. 2009, 7, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Supreme Court. N.Y. State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n v. Bruen, 142 S. Ct. 2111 (2022). Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/597/20-843/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

| Recreational Hunting (Shuryō) | Authorized Capture (Including Specified Managed Wildlife) | |

|---|---|---|

| Target species | Game species (46 species, excluding chicks and eggs) | All wildlife and eggs, including non-game species |

| Legal basis | WPMA, Art. 12 (restrictions on capture of game species) | WPMA, Arts. 8–13 |

| Purpose | No justification required | Must fall within statutory purposes (e.g., nuisance control, research) |

| Procedures | Hunting license required; annual registration before hunting season | Permit issued by prefectural governor (sometimes delegated to municipalities) |

| Season | Restricted to statutory hunting season (generally October 15–April 15) | Year-round, as authorized |

| Methods | Limited to lawful hunting methods (firearms, traps, nets) | Methods not restricted, except for prohibited dangerous practices |

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 21 August 2018 | Brown bear appeared in a residential area in Sunagawa, Hokkaido. Sunagawa City requested removal by the Hokkaido Hunting Association; one hunter discharged his firearm and killed the bear. Police officers were present at the scene; however, no shooting order was issued. |

| 24 April 2019 | Hunter’s firearm license revoked by the Public Safety Commission for firing toward a building potentially within the bullet’s range (violation of WPMA Art. 38-3). |

| 12 May 2020 | Hunter filed a lawsuit challenging the revocation. |

| 17 December 2021 | District court ruling: hunter won. Public Safety Commission appealed. |

| 18 October 2024 | High court ruling: Public Safety Commission won. Hunter filed a final appeal. |

| 18 April 2025 | WPMA amended. |

| 25 April 2025 | Amended WPMA promulgated. |

| 1 September 2025 | Amended WPMA came into effect. |

| October 2025 | Case under review in the Supreme Court (final appeal). |

| Lawsuit and Court Decisions | Differences in the District Court and High Court Decisions | Plaintiff’s Claim |

|---|---|---|

| District Court Ruling: Hunter (Plaintiff) Won | District Court: “The bullet remained inside the bear’s body. There is no evidence that it penetrated the bear and subsequently ricocheted.” | Plaintiff’s Claim: “There was an embankment approximately 8 m high, serving as a backstop.” The residents of the houses located behind the embankment likewise did not consider there to be any risk that the bullet would reach their homes. The distance was only 16.62 m, and at such a short range it was inconceivable that the plaintiff, with approximately 38 years of hunting experience, would miss the target. (General View: “If, as seen through the sight, there is a slope or the ground behind the game, it is regarded as an earthen backstop.”) Plaintiff’s Claim: “An earthen backstop was present.” |

| High Court Ruling: Public Safety Commission Won | High Court: “The bullet penetrated the bear in question and struck the stock of the hunting rifle held by B (a hunter present at the scene), passing through it. The bullet could also have ricocheted off vegetation or rocks. Behind the bear, there was no embankment or other structure sufficient to stop the bullet.” |

| Role of Municipalities | Capturers (Hunters Commissioned by Municipalities Included) | Police/Prefectural Government |

|---|---|---|

| A report is received from local residents and similar others that a bear has been sighted. | ||

| Contact is made with capturers and the police (and, if necessary, request cooperation from the prefectural government). | ||

| Gather at the site. | Gather at the site. | Gather at the site. |

| Share information, confirm the situation on site, and coordinate among relevant parties. | Cooperate with the municipality. | Cooperate with the municipality. |

| “Take measures to ensure the safety of surrounding areas. | Cooperate with the municipality. | Cooperate with the municipality. |

| Issue an order to the capturer(s) to conduct emergency shooting. | Implementation of emergency shooting. | |

| Confirm the captured individual. | Cooperate with the municipality. | Cooperate with the municipality. |

| Restore the site to its original condition. | Cooperate with the municipality. | |

| Lift the safety measures taken for surrounding areas. | Cooperate with the municipality. |

| Category | Legal Basis | Description |

|---|---|---|

| No compensation | Constitution (Kenpō), Art. 29(2) | Losses within the tolerance of property rights; no compensation required. |

| Compensation for loss | Constitution, Art. 29(3); WPMA (as amended), Art. 34-6 | Where individuals bear a “special sacrifice,” municipal mayors must compensate for ordinary losses. Property damage is expected to be covered by insurance. |

| State liability | State Redress Act (Kokka Baishō-hō), Art. 1 | Envisions claims for life, bodily integrity, and health damage. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kohyama, S. Law Reforms and Human–Wildlife Conflicts in the Living Communities in a Depopulating Society: A Case Study of Habituated Bear Management in Contemporary Japan. Wild 2025, 2, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2040047

Kohyama S. Law Reforms and Human–Wildlife Conflicts in the Living Communities in a Depopulating Society: A Case Study of Habituated Bear Management in Contemporary Japan. Wild. 2025; 2(4):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2040047

Chicago/Turabian StyleKohyama, Satomi. 2025. "Law Reforms and Human–Wildlife Conflicts in the Living Communities in a Depopulating Society: A Case Study of Habituated Bear Management in Contemporary Japan" Wild 2, no. 4: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2040047

APA StyleKohyama, S. (2025). Law Reforms and Human–Wildlife Conflicts in the Living Communities in a Depopulating Society: A Case Study of Habituated Bear Management in Contemporary Japan. Wild, 2(4), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2040047