1. Introduction

Ethnicity and ancestry are central dimensions of identity for understanding populations, particularly when considering social and health outcomes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Ethnicity is associated with a wide range of parameters that contribute to an understanding of the epidemiology of many diseases, just as ancestry informs the genetic propensities of specific groups to be subject to specific genetically based disorders and diseases. These two dimensions interact, creating complex challenges to achieving a full understanding of outcomes.

A crucial prerequisite for accurate measurement is high-quality data with sufficient detail to assess incident rates in health and social outcomes for communities [

7]. Data on migration patterns and population diversity require a level of granularity and consistency across sources. Therefore, the measurement of ethnicity and/or ancestry (preferably both dimensions) is essential for social and medical science purposes, especially when funding models and policy formulation are based, too often, on aggregated, simplistic information. The capture of these data is neither consistent across collections, nor consistent in the level of detail captured, an issue recognised globally [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Among the population subgroups of special interest are people descended from ancestors suffering the consequences of traumatic events. These include descendants of refugees, survivors of famines, and multiply-displaced diasporas. For example, Fijian Indians form part of the global Indian diaspora subjected to migration across the Pacific and Indian Oceans from India to the Caribbean, East Africa, and Fiji, as indentured labour in the 19th Century, becoming doubly diasporic as they move to other locations, often by force or coercion as political contexts change [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Confounding this particular case is the interplay of ethnic, national and heritage labels, with Fijian Indians being recorded as “Fijian” or as “Indian”. This becomes an issue because people of Fijian ethnicity (i-Taukei) have different migration and health histories that interlace with Fijian Indians in both time and space. Counting these mobile populations presents challenges, some of which have partial solutions, in this case with respect to the Fijian Indian population as we describe here, others for which measurement is more difficult, as with the Fijian ethnic population, which we signal as a topic of further research.

The objective of this paper is to analyse the available population counts for Peoples of Fiji (PF) living in Aotearoa/New Zealand (NZ), with a special focus on the subgroup most affected by ethnicity misclassifications, Fijian Indian, and to evaluate the utility of additional dimensions of identity to arrive at a more accurate count for the overall PF population. The two largest ethnic groups in Fiji are the i-Taukei (indigenous Peoples of Fiji—referred to in NZ as Fijian) and Indo-Fijian (referred to in NZ as Fijian Indian) groups. While emigration of both groups to NZ has steadily increased, the Census counts do not accurately reflect this growth. Without accurate population counts, it is nearly impossible to assess and evaluate health, wellbeing, and disease prevalence for Peoples of Fiji, and without adequate granularity, it is near impossible to address the unique health needs of this heterogenous population.

Fiji consists of an archipelago of greater than 300 islands in the South Pacific Ocean, approximately 1100 nautical miles north–northeast of New Zealand. It boasts the third largest land mass in the Pacific after Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands; and is the second most populous country in the region today after Papua New Guinea (current population exceeds 936,000). The vanua is as diverse as its peoples and cultures, comprising i-Taukei (57%), Indo-Fijian (37%), Rotuman (1%), other Pacific Islanders (1%, including Tuvaluan from Kioa, Banaban from Rabi and Ocean islands, and Tongan), Chinese (1%), and European (2.5%) [

20,

21].

After the first European landing in Fiji in 1792, European commercial interest in Fiji’s fertile land piqued. In the decades that followed, new settlers pursued economic growth within the region leading to the 1860’s plantation era in Fiji. An estimated 26,000 labourers were trafficked to Fiji from Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and Kiribati to sustain the sea island cotton and copra plantations [

22,

23]. The colonial pressures culminated in Fiji officially becoming a British crown colony in 1874. The extraordinarily high death rate among labourers of Pacific origin (who had no prior exposure to the infectious diseases introduced by settlers), led recruiters to demand labour from further afield. Between 1879 and 1920, more than 60,000 labourers migrated (under indenture) from India to Fiji through the indenture system/Girmit, a system developed in the West Indies upon the abolition of slavery in 1833, to work on the plantations and sustain the colonial economy [

24,

25].

It is the descendants of indentured labourers who form much of the Fijian Indian population alive today. This group has a distinct cultural identity that combines elements of Indian heritage with influences from Fiji’s diverse cultural landscape. For example, Fijian Indians typically speak Fiji Hindi, a koiné language [

26,

27]. Remnants of a creole variously referred to as Fiji Baat or Pidgin Hindi can also still be heard [

28]. The population in Fiji has decreased with the ethno-political instability associated with each successive coup d’état in Fiji (see

Appendix A,

Table A1); this has correlated with increased rates of PF emigration to NZ, Australia, Canada, and the USA. Over the last four decades, the PF population, living in NZ, has grown considerably; however, this growth is not accurately reflected in Census data.

The concern for an effective count for Peoples of Fiji is not new [

29]. An investigation into ethnicity was undertaken by Statistics NZ, prior to 2005, contributing to ongoing research into potential ways in which Censuses could be derived from or augmented by administrative data sources [

30,

31]. It was found that each administrative data source had more people recorded as Fijian than the number of people identifying with the Fijian ethnic group according to the Census. For example, more than two-thirds of individuals identifying as Fijian Indian in the Census were coded as Fijian in the Ministry of Education tertiary data [

30]. These examples highlight the necessity for improved ethnicity coding and data collection quality. The risk of misidentifying minority groups can lead to misallocation of resources and to underserving populations facing greater health inequities.

The ethnicity data protocols issued by the Ministry of Health noted that there have been data quality issues in the recording of Fijian Indian respondents and stated: “The Ethnicity New Zealand Standard Classification codes “Fijian Indian” as Level 4 code 43112 (which aggregates at Level 1 output to “Asian”). Some respondents and some providers have chosen to alter collection forms or allow respondents to select “Fijian” and “Indian” separately. This creates two codes—“Fijian 36111 (Level 1 Pacific Peoples)” and “Indian 43100 (Level 1 Asian)”—with prioritised output (see

Appendix B), this aggregates to “Level 1 Pacific Peoples”. This has implications for funding formulae and health status monitoring for both Pacific and Asian populations. Respondents identifying as “Fijian Indian” must be coded 43112”.

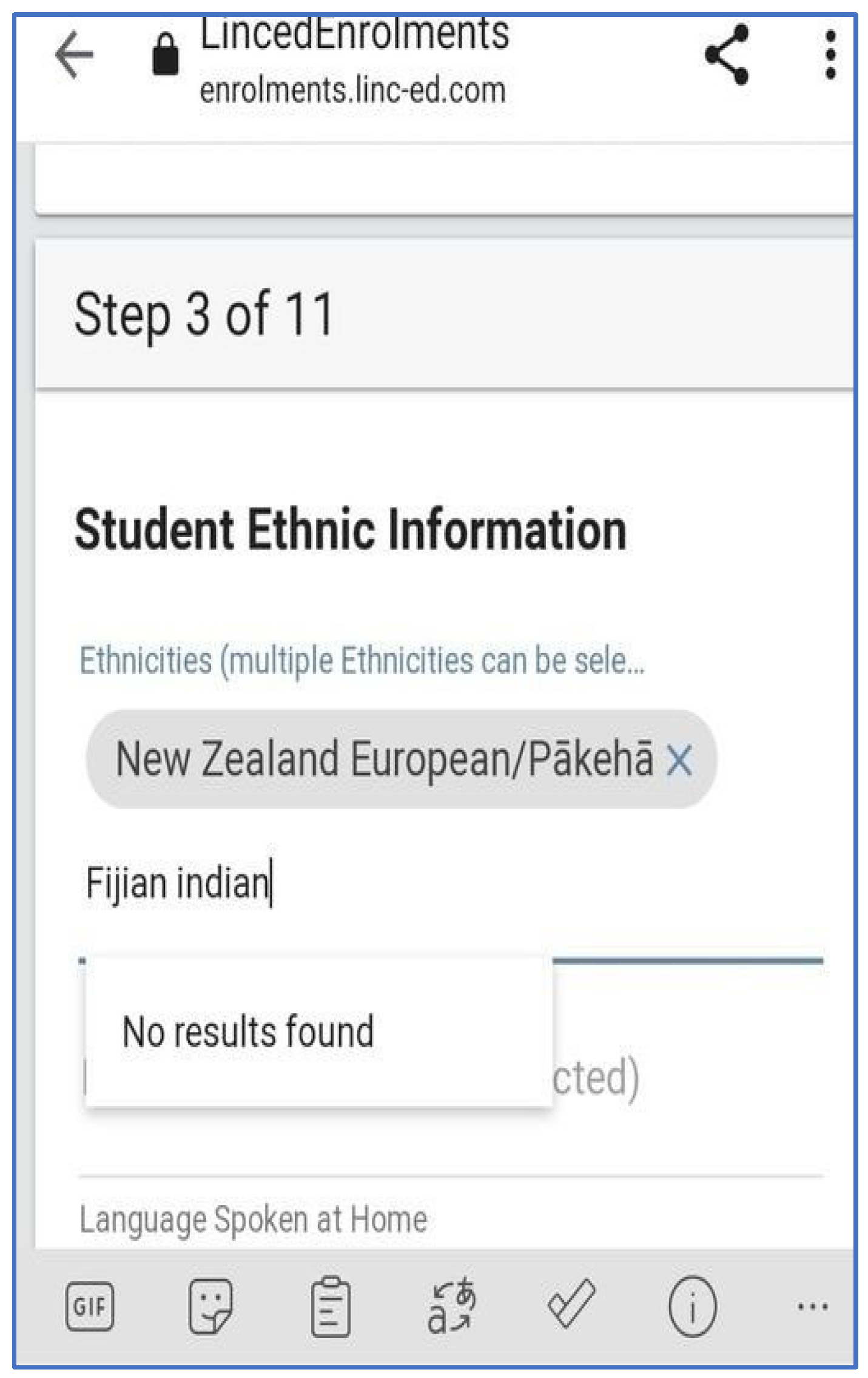

However, in practice, most administrative data collection across, for example, schools, hospitals, and medical centres, lacks the administrative infrastructure to select accurate ethnicity codes and put such guidelines into practice. For example, in electronic platforms, respondents are frequently unable to select Level 4 ethnic codes, because the drop-down menus only offer up to Level 2 ethnic code options. To change the drop-down menu options for ethnicity across all administrative databases would require a mandated change to ensure consistent collection; however, this has not been instigated nationally to date.

Figure 1 depicts a screenshot of an online enrolment form currently used within the education sector in NZ. The response “No results found” is returned when for example “Fijian Indian” is entered into the “student ethnic information” field. To progress through such forms, one must select at least one option that returns a “valid” result. In the absence of options that relate to Level 4 codes such as “Fijian Indian”, no matter how motivated a respondent is to accurately capture their ethnicity, the options “Fijian” or “Indian”, or a combination of the two, are likely selected to enable the respondent to complete and submit the enrolment form.

Furthermore, when information is coded in the Census process, text responses are edited and transformed to meet a preset classification. For example, when a respondent enters “Fiji Indian”, “Fijian Indian”, or “Indo-Fijian”, as one of their ethnicities, this will be coded as 43112 (Fijian Indian). However, if “Indian Fijian” is stated by a respondent, this may be recorded as two ethnicities—Indian (43100) and Fijian (36100)—when it is unclear whether one response or two is being provided. Such processing has the potential to introduce a mismatch between what the respondent intended as their ethnic identification and how it is coded and later interpreted. The numerical representation of ethnic counts should not overshadow the significance of the social context itself.

The objectives of this paper are (a) to estimate the growth and current size of the population from Fiji that now lives in NZ using ethnicity and other data dimensions from available Censuses, and (b) to provide a revised estimate for the two largest ethnic groups contributing to the PF population count, using additional dimensions such as country of birth and parental ethnicity. In this paper, we outline the growth and current size of the population from Fiji that now lives in NZ. This is a crucial step in deriving a denominator of total population size that correlates with the resident population and therefore can be used to estimate and monitor changes in, for example, access to health, education, and social welfare services for this population over time.

3. Results

This section illustrates how populations from Fiji moving to NZ have grown over time and additional dimensions that assist in estimating a more accurate combined total of the now resident population in NZ. People of Fijian ethnicity (the classification label used in NZ for i-Taukei) and Fijian Indian ethnicity may be born in Fiji, NZ, or elsewhere, contributing to the growth of the ethnic communities in NZ.

3.1. Population Change for Fijian Ethnicity over Time

Gendered migration from the Pacific region to NZ, overall, from the 1950s through to the 1990s favoured women because of labour opportunities [

33]. Fijian migration differed in this respect. As shown in

Table 1, the number of respondents identifying with Fijian ethnicity increased steadily from 1976 to 2018, with the largest increase (146%) observed after 2006. This surge potentially coincides with significant emigration from Fiji following the 2006 coup [

34,

35]. The gender distribution remained relatively balanced, with 5.2% more men than women, possibly due to the influx of male seasonal workers in this period or a higher likelihood of Fijian Indian men identifying along nationality lines.

3.2. Population Change for Fijian Indian Ethnicity over Time

Table 2 summarises the growth of the Fijian Indian population from 1991 to 2018. Significant increases were observed following the 1987 (253%), 2000 (202%), and 2006 (81%) coups [

36,

37,

38,

39]. As expected for recent migration flows, most respondents were born in Fiji, albeit with an emerging component of the population born in NZ.

3.3. Population Change for the Fiji-Born Population over Time

Consistent with the previous tables,

Table 3 shows the number of people resident in NZ but born in Fiji significantly increasing after each coup. The numbers are nearly double the combined total of respondents coded as Fijian and Fijian Indian. A large proportion of the counts correlate with people born in Fiji who are coded to Indian ethnicity 43000 (see

Table 4); this indicates the scale of the potential misclassification of ethnic groups from Fiji, especially of Fijian Indians. These counts also include people of other ethnicities such as i-Kiribati or Rotuman or people of European ethnicities born in Fiji, as well as people without specified ethnicities, albeit in smaller numbers.

3.4. Misclassification in Ethnicity

Table 4 highlights a significant misclassification issue in Census data. Many Fijian Indians were recorded simply as “Indian” due to the presence of a tick box labelled “Indian” [

40]. In 1976, the Indian population in NZ exceeded 10,000, with 47% born locally and 15% born in Fiji. By 2018, this population had grown to 239,193, with 20% born in Fiji. Consistent with patterns emerging in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3, the growth correlates with migration surges following the Fijian coups of 1987, 2000, and 2006 (see also

Appendix A).

Within the context of this paper, the 49,365 Fiji-born Indians in New Zealand may be regarded as Fijian Indian. This is consistent with the small number (1400) of Non-Resident Indians (NRIs), registered as overseas citizens of India, residing in Fiji out of a total Indian-origin population of 315,198, as reported by India’s Ministry of External Affairs [

41]. A similar trend is observed in Australia, where the 2021 Census recorded 68,947 Fiji-born individuals coded with Indian ethnicity, 58% of whom spoke Fijian Hindustani (as Fiji Hindi is labelled in Australian data).

3.5. Ethnicity of Children with a Fijian Indian Parent

Table 5 tabulates children who did not identify as Fijian Indian but lived with at least one Fijian Indian parent. In the 2018 Census, 15,711 children met this criterion. This count refers only to people coded as a child resident with a family on Census Night, by definition living at home with a parent. This excludes children not living with their parents on Census Night.

Using the NZ Linked Census longitudinal data, we can estimate the number of individuals who would be classified as children of Fijian Indian parentage not in a Census family in 2018 because they were no longer living at home. Given that the Fijian Indian diaspora in NZ is a relatively recent migrant population, by 2018, only a small number of children were old enough to fall into this category. This suggests that a minimum additional 2568 people may be of Fijian Indian descent, and by implication ethnicity, according to these criteria. These counts are included in the 18,279 total for children of Fijian Indian parents in

Table 6 below.

Associated with differences in ethnic identification of children is the phenomenon of ethnic mobility [

42]. Ethnicity, as defined and operationalised in NZ, is self-defined and people may legitimately change their ethnicities over time and in response to changing environments. We have made assumptions here that the coding issues far outweigh the expected level of ethnic mobility for children both living at home and who have left home. Uncertainties in the available data do not invalidate our assumption that these people have at least some Fijian Indian ancestry, and that this is equivalent to Fijian Indian ethnicity for the purposes of estimating a more accurate total count for PF.

3.6. Towards a Revised Estimate Population Count for Peoples of Fiji

An accurate denominator for PF is dependent on the reliable representation of the diverse groups that fall within this larger grouping. While we can be confident the 2023 Census ethnic group summaries for Fijian code 36100 and Fijian Indian code 43112 (25,038 and 23,808 respectively) belong in the PF denominator, they remain a significant undercount for the total PF population based on the 2018 counts shown in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5.

Table 6 provides a revised estimate of the Fijian Indian subgroup which is most affected by the misclassification in NZ, totalling 73,056 people (31% of the total Indian population resident in NZ on Census Night in 2018) and brings the revised estimate for the PF denominator to 92,778 for 2018.

The Fijian Indian revised estimate incorporates additional dimensions of identity such as ethnicity, birthplace, and language spoken. To the count of people identifying with at least one ethnic code as Fijian Indian (n = 15,132), we added the number of people recorded as “Indian ‘not further defined’ (nfd)” with country of birth, Fiji (n = 38,190). The estimate of children of Fijian Indian parentage, who were living with their parents on Census Night but were not themselves coded as Fijian Indian, together with children who had left home, estimated through the NZ Linked Census longitudinal data, made it possible to add an estimated further 18,279 people.

Arguably, we can include other people who speak Fiji Hindi but did not report any of the above ethnicity criteria. There were 1365 people who were Fiji-born speakers of Fiji Hindi but not coded as Indian or Fijian Indian. In addition, there is a small number of NZ-born Fiji-Hindi or Hindi speakers of Fijian ethnicity who were not coded as either Indian or Fijian Indian (n = 90) who have been, tentatively, included in our revised estimate.

One dimension of identity that we chose not to include here was religious affiliation. Religion is in many cases closely associated with ethnicity [

43,

44,

45]. The NZ Census routinely collects religious affiliations, and as with ethnicity, people may report multiple affiliations. The population of Fiji is religiously diverse. Adherents of Islam and Hinduism could be assumed more likely to be Fijian Indian. A significant proportion of both the i-Taukei and Fijian Indian populations follow Christian religions. The most recently available data from Fiji on religious affiliation by ethnicity (1996 Census) [

46] indicated that there were some i-Taukei adherents of Islam, as expected, and, less expected, of Hinduism. The 2018 NZ Census data suggested that there were 1125 people coded to Fijian ethnicity who were adherents of Hinduism and 522 Muslims of Fijian ethnicity who may potentially be Fijian Indian. There are known cases where this reflected genuine religious affiliation, but equally could mean that either religion or ethnicity was in error. With no alternative discriminating information, it was decided to exclude these 1647 people from our consideration for this paper.

Similarly, there were 645 people who were born in NZ and coded as having both Fijian and Indian ethnicities but were not recorded as speakers of Hindi or Fiji Hindi. These would not have been captured in the filters used above. While it might be fair to assume that the “Indian” coding could be interpreted as “Fijian Indian”, it was not sufficiently clear whether this was a coding issue, ethnic mobility at work, individuals genuinely identifying with multiple ethnicities, or a reflection of interethnic partnering. These counts were therefore also excluded from our estimation.

Census net undercount is a further source of uncertainty that will tend to result in an under-estimation of communities. The 2018 Census Post Enumeration Survey (PES) found that ethnicities within the broad Asian and Pacific groupings had a net undercount of 3.3% and 4.9% respectively [

47]. The sample for the PES was too small to estimate coverage at a more detailed ethnic level. Considering that the primary issue with PF counts pertains to the Fijian Indian ethnic grouping, this paper demonstrates that these counts significantly differ from the Census data. Developing similar methods to identify the undercount of the Fijian ethnic groups remains to be done.

4. Discussion

The results of this study highlight the significant undercount of populations originally from Fiji in NZ’s Census data. This undercount is primarily due to the limitations of the ethnicity data, which fails to capture the complexity of minority migrant groups [

48]. Previous studies have similarly noted the challenges of accurately representing diverse populations using a single ethnic category [

29,

30]. The additional granularity obtained from dimensions such as country of birth and language spoken demonstrates their utility in providing revised estimates for population counts and delineating the demographic characteristics of the groups of interest.

Ethnic mobility, where an individual’s ethnic identification changes over time and between contexts, further complicates the interpretation of Census data [

49]. This phenomenon is particularly prevalent among younger age groups in NZ, who may identify with multiple ethnicities or as “New Zealander”, changing their ethnicities as they progress through life stages. The absence of a dedicated tickbox for Fijian Indians and the misclassification of people because of the presence of the “Indian” tickbox further exacerbates the undercount. Language barriers and the failure, in some collections (such as health and education administrative data), to account for Level 4 codes also contribute to the inaccuracies.

The implications of these findings are significant. Accurate population data are crucial for effective health planning, early intervention in health risks, and equitable resource allocation across education, health, and social services. The undercount of the Fijian and Fijian Indian populations means that these communities are likely underserved in these areas. Compared to the UK and US, data for ethnicity are collected for over 200 different ethnic groups in NZ; however, despite the potential to collect and report extremely granular data, government agencies and academia frequently collapse the granularity to a handful of heterogenous ethnic categories for reporting purposes [

50]. Grouping multiple heterogenous groups together has the potential to mask important inequalities. We see this in Fiji. The constant pooling of data in Fiji, placing both i-Taukei and Indo-Fijian groups into one heterogenous group masks the health risks that affect one group more than the other [

50]; for example, diabetes-related limb complications are more prevalent among i-Taukei [

51,

52], while diabetes-related kidney complications are more common among Indo-Fijian [

53]. When the results are pooled, the risks unique to each respective group become masked or averaged out.

The debate over modifying the ethnicity classification to include all relevant subgroups within a higher-level grouping of ethnicities as a “Fijian” category involves compelling arguments on both sides.

There is an argument for redefining the Level 2 category “Fijian” to include all the PF centres on whether or not Fijian Indian should be an ethnicity within the Level 1 Pacific grouping of ethnicities, or should remain in the Level 1 Asian grouping of ethnicities. The current NZ classification system does include subgroups such as Fijian (i-Taukei as a synonym), Rotuman, and Fijian Indian (Indo-Fijian as a synonym), but includes Fijian Indian as a subgroup under the Level 2 category Indian and the Level 1 group Asian. Similarly, Rotuman is included under “Other Pacific” because it is an ethnicity distinct from Fijian. “Fijian” is a nationality, not an ethnicity, and thus could be broken down into more specific categories. By comparison, the “Indian” category in New Zealand’s ethnic classification system encompasses a range of distinct South Asian ethnicities with different ancestries and geographic origins—such as those from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka—yet they are often pooled together under a broader “Asian” category [

54]. Ethnicity is a social construct with, in some views, limited biological basis [

55], and is a relatively subjective, self-determined identification that can change throughout life [

48]. With increasing numbers of people who identify with multiple ethnicities [

42], the utility of this dimension in distinguishing between distinct people groups becomes increasingly complex [

56]. This contrasts with ancestry, which is a dimension that is assumed to remain static for an individual throughout life and can be correlated with extreme environments such as prolonged famine exposure, and the initial exposure of an isolated population to an infectious disease. Additionally, as demonstrated by limb versus renal complications among i-Taukei versus Indo-Fijian groups respectively in Fiji, it is important to distinguish between subgroups at a more granular level of detail when the underpinnings of disease differ in cause. This granularity can help address specific health needs linked to place of origin and ancestry especially when paired with other metrics like birthweight and urban/rural status. The view is supported by sections of the Fijian Indian and Fijian communities. The inclusion of Fijian Indian and i-Taukei subgroups within the Fijian grouping is appropriate and necessary for effective policy-making with respect to the Pacific region.

The argument against changing the classification structure stems from operational difficulties in the collection of ethnicity data. The term “Fijian” can refer to nationality when discussing birthplace and citizenship, but, in English, it is generally used to mean i-Taukei ethnicity. In Na Vosa vaka-Viti (Fijian language), the word i-Taukei translates in English to “owners of the land” [

57]. The Fijian Indian community is seen as quite distinct, with different socio-economic and social histories. Rotuman, with roots in central Polynesia, is an ethnicity within the Pacific grouping of ethnicities, and its political connection to Fiji is a separate issue [

58]. It is acknowledged that the current classification is already a mix of ethnicities, ancestries, nationalities, and religions, making it complex [

40,

59,

60]. A key issue is that many data collection tools, including Census paper forms, use a simplified tickbox labelled “Indian” for ease of classification. Accurately capturing the identity of Fijian Indians would require a more nuanced approach before considering their reassignment to the Pacific ethnic grouping. One potential solution could be to add more granularity—such as introducing a distinct “Fijian Indian” tickbox and collecting information on the country of birth of respondents and their parents. However, this added complexity may pose challenges for both data collection and analysis, especially given the limitations of the current data ecosystem.

There is also widespread misunderstanding about how greater ethnic data granularity might impact funding. Some fear it could divert resources away from the i-Taukei population. However, as this article highlights, the existing discrepancies between data sources—such as mismatched numerators and denominators—suggest that current statistics on Peoples of Fiji living in New Zealand already have limited influence on funding decisions.

Improving the ethnicity standard for major groups of Fijian origin in NZ requires a multifaceted strategy. A balanced approach could involve a phased implementation of subgroups, starting with extensive consultations with the communities of interest to ensure their perspectives and needs are adequately represented. This community-driven approach will help identify specific areas requiring attention and ensure that health, social, and education services are tailored to meet the unique needs of people from Fiji. One key approach is to enhance capability through scholarships for ethnic minority groups, enabling them to become proficient in using microdata, such as the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) [

61], for more granular exploration of ethnicity and birthplace information. In addition, given the established link between birthweight and the developmental origins of diseases such as diabetes and heart disease [

62,

63], incorporating birthweight as a function of gestational age and ethnic group into diabetes and CVD risk assessments and routine screening could enhance the effectiveness of risk classification system within the health context, particularly for ethnic minority groups. Finally, campaigns to promote awareness about the importance of accurate ethnicity data collection among healthcare providers and the community require better resourcing and collaboration.

Future research should focus on developing methods to account for ethnic mobility and its impact on population counts. Additionally, there is a need for more inclusive data collection practices that capture the diversity of minority groups (both migrant and locally born), a problem not unique to NZ [

64]. This could include the use of additional dimensions such as ancestry and birthplace, which can provide a more comprehensive view of the population and help in predicting health risks. This is particularly relevant for groups who have experienced (or descend from) extreme environments of famine or trauma.