Emotional Congruence in Childhood: The Influence of Music and Color on Cognitive Processing

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Developmental Effect: Attentional performance (processing speed) would increase with age, reflecting the maturation of the prefrontal cortex and the subsequent strengthening of inhibitory control and processing capacity.

- Congruence Effect: Guided by the Emotional Congruence Model (Bower, 1981), we predicted that performance would be optimized when the task’s visual context (color) matched the prior emotional state (music). Specifically, congruence should act as a ‘cognitive facilitator’, reducing the executive load required to filter irrelevant information compared to incongruent conditions. While the Emotional Congruence Model (Bower, 1981) suggests a symmetrical facilitation effect for both positive and negative states through the activation of valence-specific cognitive nodes, developmental literature often reports an asymmetrical ‘positivity bias’ in early childhood (Boseovski, 2010). Younger children may show a greater sensitivity to positive congruence (joy) due to the early maturation of approach-related affect systems. However, we maintain a symmetrical hypothesis as a baseline to test whether the fundamental mechanism of emotional priming, whereby any mood-congruent cue reduces cognitive load, is already operational across both valences in our age range.

2. Methods

- Study 1: Music as an Emotional Inducer

2.1. Participants

2.2. Recruitment Procedures

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Materials

2.4.1. Music

2.4.2. Emotional Self-Assessment Scale

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analyses (Study 1)

- Study 2: Dual Emotional Induction and Attentional Tasks

2.7. Participants

2.8. Ethical Considerations

2.9. Recruitment Procedures

2.10. Materials

2.10.1. Music

2.10.2. Cancellation Task

2.10.3. Emotional Self-Assessment Scale

2.11. Procedure

2.12. Statistical Analyses (Study 2)

3. Results

3.1. Results of Study 1

3.1.1. Analysis of the Effects of Emotional Induction Through Music

3.1.2. Analysis of the Effects of School Level on State Variation After Joy Induction

3.1.3. Analysis of the Effects of School Level on State Variation After Sadness Induction

3.2. Results of Study 2

3.2.1. Analysis of the Effects of Emotional Inductions on Selective Attention

3.2.2. Analysis of the Effects of Emotional Congruence on Selective Attention

3.2.3. Analysis of the Effect of Emotional Induction on the Child’s Experienced Emotion

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. A. (Ed.). (2014). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bellinghausen, L. (2012). Quel est le futur des compétences émotionnelles dans les dispositifs de formation professionnelle? Pédagogie Médicale, 13(3), 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benintendi, S., Simoës-Perlant, A., Lemercier, C., & Largy, P. (2016). Effet d’une induction émotionnelle par la couleur sur l’attention d’enfants typiques de 4 à 11 ans. Approche Neuropsychologique des Apprentissages chez L’enfant, 145, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette, I. (2006). The effect of emotion on interpretation and logic in a conditional reasoning task. Memory & Cognition, 34(5), 1112–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bodenhausen, G. V., Kramer, G. P., & Süsser, K. (1994). Happiness and stereotypic thinking in social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(4), 621. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/adad/9072c3ef26d6050b8996d7e65360b2181cc2.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2019). [CrossRef]

- Boseovski, J. J. (2010). Evidence for “Rose-Colored Glasses”: An Examination of the Positivity Bias in Young Children’s Personality Judgments. Child Development Perspectives, 4, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36(2), 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25(1), 49–59. Available online: https://www.axessresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/AffectivePictureSystemSelfMesurement.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2019). [CrossRef]

- Brainerd, C. J., Holliday, R. E., Reyna, V. F., Yang, Y., & Toglia, M. P. (2010). Developmental reversals in false memory: Effects of emotional valence and arousal. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 107(2), 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, E. (2000). Mood induction in children: Methodological issues and clinical implications. Review of General Psychology, 4(3), 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretié, L., Hinojosa, J. A., Martín-Loeches, M., Mercado, F., & Tapia, M. (2004). Automatic attention to emotional stimuli: Neural correlates. Human Brain Mapping, 22(4), 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caverni, J. P. (1998). Pour un code de conduite des chercheurs dans les sciences du comportement humain. L’année Psychologique, 98(1), 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, C. T., & Johnston, C. (2002). Developmental differences in children’s use of the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) to rate pictures from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS). Psychology & Health, 17(5), 625–638. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, P. M., Martin, S. E., & Dennis, T. A. (2004). Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development, 75(2), 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkum, P., McKinnon, A. L., & Mullane, J. C. (2005). The assessment of attention in preschool-aged children. Child Neuropsychology, 11(3), 287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A. (2003). Feelings of Emotion and the Self. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1001, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. (1984). Expression and the nature of emotion. In Approaches to emotion (pp. 19–344). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, H. C., & Moore, B. A. (1999). Mood and memory. In T. Dalgleish, & M. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion (pp. 193–210). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, M., Pine, D. S., & Hardin, M. (2006). Triadic model of the neurobiology of motivated behavior in adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 36(3), 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M. W., & Byrne, A. (1992). Anxiety and susceptibility to distraction. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(7), 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fartoukh, M., Chanquoy, L., & Piolat, A. (2014). Influence d’une induction émotionnelle sur le ressenti émotionnel et la production orthographique d’enfants de CM1 et de CM2. L’Année Psychologique, 114(2), 251–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, K., & Bless, H. (2001). Social cognition. In M. Hewstone, & W. Stroebe (Eds.), Introduction to social psychology, an European perspective (3rd ed., pp. 114–149). Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Gutiérrez, E. O., Díaz, J. L., Barrios, F. A., Favila-Humara, R., Guevara, M. Á., del Río-Portilla, Y., & Corsi-Cabrera, M. (2007). Metabolic and electric brain patterns during pleasant and unpleasant emotions induced by music masterpieces. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 65(1), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrielsson, A., & Lindström, E. (2010). The role of structure in the musical expression of emotions. In P. N. Juslin, & J. A. Sloboda (Eds.), Music and emotion: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 367–400). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, L., & Peretz, I. (2003). Mode and tempo relative contributions to “happy-sad” judgements in equitone melodies. Cognition & Emotion, 17(1), 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilet, A. L. (2008). Procédures d’induction d’humeurs en laboratoire: Une revue critique [Mood induction procedures: A critical review]. L’encéphale, 34, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golse, B. (2010). L’émotion dépressive et la co-construction des affects et des représentations. In Dépression du bébé, dépression de l’adolescent (pp. 37–53). ERES. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, F. (2012). Affective valence of words impacts recall from auditory working memory. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 24(2), 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, F., Kikuchi, T., & Roßnagel, C. S. (2008). Emotional interference in enumeration: A working memory perspective. Psychology Science, 50(4), 526–537. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Fumiko_Gotoh/publication/26569019_Emotional_interference_in_enumeration_A_working_memory_perspective/links/ (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Habibi, A., & Damasio, A. (2014). Music, feelings, and the human brain. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 24(1), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herba, C. M., Landau, S., Russell, T., Ecker, C., & Phillips, M. L. (2006). The development of emotion-processing in children: Effects of age, emotion, and intensity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, P. G., Schellenberg, E. G., & Schimmack, U. (2010). Feelings and perceptions of happiness and sadness induced by music: Similarities, differences, and mixed emotions. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 4(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallais, C., & Gilet, A. (2010). Inducing changes in arousal and valence: Comparison of two mood induction procedures. Behavior Research Methods, 42(1), 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janvier, B., & Testu, F. (2005). Développement des fluctuations journalières de l’attention chez des élèves de 4 à 11 ans. Enfance, 57(2), 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S. (2014). Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(3), 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, P., Oravecz, Z., & Tuerlinckx, F. (2010). Feelings change: Accounting for individual differences in the temporal dynamics of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(6), 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, J. I., LaBar, K. S., & Meck, W. H. (2016). Emotional modulation of interval timing and time perception. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 64, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largy, P., Simoës-Perlant, A., & Soulier, L. (2018). Effet de l’émotion sur l’orthographe d’élèves d’école primaire. Swiss Journal of Educational Science, 40(1), 191–216. Available online: https://hasbonline.unibe.ch/index.php/sjer/article/download/5059/7354 (accessed on 6 November 2019). [CrossRef]

- Lima, C. F., & Castro, S. L. (2011). Emotion recognition in music changes across the adult life span. Cognition and Emotion, 25(4), 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, J. A., Beauchamp, M. H., Crigan, J. A., & Anderson, P. J. (2014). Age-related differences in inhibitory control in the early school years. Child Neuropsychology, 20(5/6), 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNamara, A. (2025). Engagement and disengagement: From the basic science of emotion regulation to an anxiety spectrum. Psychophysiology, 62, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynova, E. N., & Lyusin, D. (2025). The role of stimuli valence and arousal in emotional word processing: Evidence from the emotional Stroop task. Psihologija, 58(3), 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., Allen, J. P., & Beauregard, K. (1995). Mood inductions for four specific moods: A procedure employing guided imagery vignettes with music. Journal of Mental Imagery, 19(1–2), 133–150. Available online: http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-10385-001 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Mikolajczak, M., Quoidbach, J., Kotsou, I., & Nelis, D. (2009). Les compétences émotionnelles. Dunod. [Google Scholar]

- Monnier, C., & Syssau, A. (2017). Affective norms for 720 French words rated by children and adolescents (FANchild). Behavior Research Methods, 49(5), 1882–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsell, A. H. (1929). Book of color. Munsell Color. [Google Scholar]

- Oaksford, M., Morris, F., Grainger, B., & Williams, J. (1996). Mood, reasoning, and central executive processes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 22(2), 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, S. W., & Papalia, D. E. (2005). Le développement de la personne (A. Brève, Ed.; 6th ed.). Études Vivantes. [Google Scholar]

- Öhman, A., Flykt, A., & Esteves, F. (2001). Emotion drives attention: Detecting the snake in the grass. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecchinenda, A., & Petrucci, M. (2021). Emotion first: Children prioritize emotional faces in gaze-cued attentional orienting. Psychological Research, 85(1), 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelet, J. (2010). Effets de la couleur des sites web marchands sur la mémorisation et sur l’intention d’achat. Systèmes D’information & Management, 15(1), 97–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Lloret, S., Braidot, N., Cardinali, D., Delvenne, A., Diez, J., Dome, M., & Vigo, D. (2014). Effects of different “relaxing” music styles on the autonomic nervous system. Noise & Health, 16, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, E., Brosch, T., Delplanque, S., & Sander, D. (2016). Attentional bias for positive emotional stimuli: A meta-analytic investigation. Psychological Bulletin, 142(1), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M. I., Walker, J. A., Friedrich, F. J., & Rafal, R. D. (1984). Effects of parietal injury on covert orienting of attention. Journal of Neuroscience, 4(7), 1863–1874. Available online: https://www.jneurosci.org/content/jneuro/4/7/1863.full.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2019). [CrossRef]

- Rader, N., & Hughes, E. (2005). The influence of affective state on the performance of a block design task in 6- and 7-year-old children. Cognition and Emotion, 19(1), 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A. E., Chan, L., & Mikels, J. A. (2014). Meta-analysis of the age-related positivity effect: Age differences in preferences for positive over negative information. Psychology and Aging, 29(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, M. R., Posner, M. I., & Rothbart, M. K. (2005). The development of executive attention: Contributions to the emergence of self-regulation. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28(2), 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarni, C. (2000). Emotional competence: A developmental perspective. In R. Bar-On, & J. D. Parker (Eds.), Handbook of emotional intelligence (pp. 68–91). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, D., Grandjean, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2005). A systems approach to appraisal mechanisms in emotion. Neural Networks, 18, 317–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoës-Perlant, A., & Lemercier, C. (2018). Evaluation du lexique émotionnel chez l’enfant de 8 à 11 ans. ANAE-Approche Neuropsychologique des Apprentissages Chez L’enfant, 155, 417–423. Available online: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01865361/document (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Sinclair, R. C., Soldat, A. S., & Mark, M. M. (1998). Affective cues and processing strategy: Color-coded examination forms influence performance. Teaching of Psychology, 25, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E., & Kosslyn, S. (2009). Cognitive psychology: Mind and brain. Pearson International Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Soldat, A. S., Sinclair, R. C., & Mark, M. M. (1997). Color as an environmental processing cue: External affective cues can directly affect processing strategy without affecting mood. Social Cognition, 15(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., Fabes, R. A., Valiente, C., Shepard, S. A., Reiser, M., Losoya, S. H., & Guthrie, I. K. (2006). Relation of emotion-related regulation to children’s social competence: A longitudinal study. Emotion, 6(3), 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storbeck, J. (2013). Negative affect promotes encoding of and memory for details at the expense of the gist: Affect, encoding, and false memories. Cognition & Emotion, 27(5), 800–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syssau, A., & Monnier, C. (2012). The influence of the emotional positive valence of words on children memory. Psychologie Française, 57(4), 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z., Lui, X., Song, Y., Guan, H., Wen, X., Hu, S., & Lu, M. (2025). The influence of odors on cognitive performance based on different olfactory preferences. Building and Environment, 271(1), 112603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trick, L. M., & Enns, J. T. (1998). Lifespan changes in attention: The visual search task. Cognitive Development, 13(3), 369–386. Available online: http://visionlab.psych.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2015/06/45_TrickEnnsCD98.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2019). [CrossRef]

- Van der Zwaag, M. D., Westerink, J. H., & Van Den Broek, E. L. (2011). Emotional and psychophysiological responses to tempo, mode, and percussiveness. Musicae Scientiae, 15(2), 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauclair, J. (2004). Développement du jeune enfant: Motricité, perception, cognition. Belin. [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier, P., & Huang, Y. M. (2009). Emotional attention: Uncovering the mechanisms of affective biases in perception. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(3), 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuoskoski, J. K., & Eerola, T. (2011). Measuring music-induced emotion: A comparison of emotion models, personality biases, and intensity of experiences. Musicae Scientiae, 15(2), 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, D. T., Petty, R. E., & Smith, S. M. (1995). Positive mood can increase or decrease message scrutiny: The hedonic contingency view of mood and message processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(1), 5. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4b01/9d8536627900916d0c6f7334c03573b34ee0.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westermann, R., Spies, K., Stahl, G., & Hesse, F. W. (1996). Relative effectiveness and validity of mood induction procedures: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26(4), 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiend, J. (2010). The effects of emotion on attention: A review of attentional processing of emotional information. Cognition and Emotion, 24(1), 3–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D., Morris, I. F., Qu, L., & Kesek, A. C. (2024). Hot executive function: Emotion and the development of cognitive control. In M. A. Bell (Ed.), Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition (2nd ed., pp. 51–73). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Joy Induction | Sadness Induction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valency | Arousal | Valency | Arousal | |||||

| School Level | M(SD) T1 | M(SD) T2 | M(SD) T1 | M(SD) T2 | M(SD) T1 | M(SD) T2 | M(SD) T1 | M(SD) T2 |

| Preschoolers | 5.69 (1.45) | 6.13 (1.1) | 4.94 (2.21) | 5.56 (2.07) | 6.53 (0.84) | 4.21 (1.93) | 4.21 (2.25) | 4.05 (2.42) |

| Second graders | 5.44 (1.1) | 6.69 (0.60) | 4.63 (1.67) | 6 (0.89) | 5.5 (0.97) | 2.31 (0.7) | 3 (1.59) | 2.75 (1.53) |

| Fourth graders | 5.38 (0.96) | 4.12 (0.82) | 4.56 (1.32) | 3.56 (1.71) | 5.38 (0.96) | 3 (0.82) | 4 (1.32) | 3.56 (1.71) |

| Fifth graders | 5.19 (0.91) | 6.38 (0.62) | 3.94 (1.34) | 5.5 (0.97) | 5.5 (0.73) | 2.44 (0.96) | 4 (1.37) | 3.19 (1.38) |

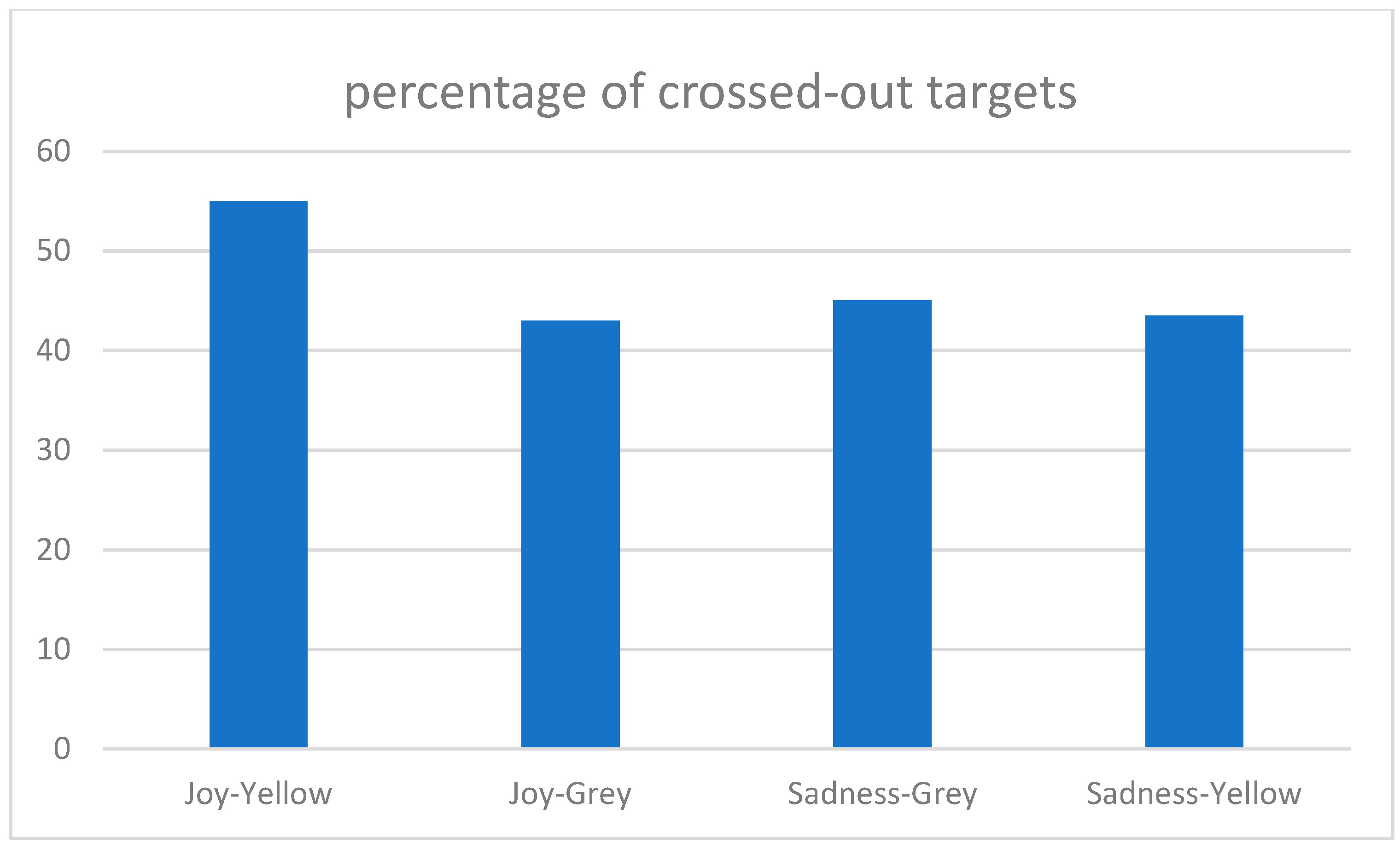

| Emotional Condition | Music Valence | Background Color | Mean (%) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congruent Positive | Joyful | Yellow | 55.16 | 27.34 |

| Incongruent | Joyful | Gray | 43.21 | 23.56 |

| Congruent Negative | Sad | Gray | 45.15 | 22.80 |

| Incongruent | Sad | Yellow | 49.91 | 27.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Simoës-Perlant, A.; Benintendi-Medjaoued, S.; Gramaje, C. Emotional Congruence in Childhood: The Influence of Music and Color on Cognitive Processing. Psychol. Int. 2026, 8, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint8010006

Simoës-Perlant A, Benintendi-Medjaoued S, Gramaje C. Emotional Congruence in Childhood: The Influence of Music and Color on Cognitive Processing. Psychology International. 2026; 8(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint8010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimoës-Perlant, Aurélie, Sarah Benintendi-Medjaoued, and Camille Gramaje. 2026. "Emotional Congruence in Childhood: The Influence of Music and Color on Cognitive Processing" Psychology International 8, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint8010006

APA StyleSimoës-Perlant, A., Benintendi-Medjaoued, S., & Gramaje, C. (2026). Emotional Congruence in Childhood: The Influence of Music and Color on Cognitive Processing. Psychology International, 8(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint8010006