During the COVID-19 Pandemic, the Gap in Career Awareness Between Urban and Rural Students Widened

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Review of Previous Studies and Hypotheses

1.2. Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- Regarding intended employment type immediately after graduation, the most common choice among urban students was “working in a large company” (35.0%), while among rural students it was “working in a small or venture company” (44.1%).

- For intended industry immediately after graduation, excluding those who answered “undecided” (urban: 24.3%; rural: 25.6%) or “no particular preference” (urban: 9.9%; rural: 12.8%), the most frequent responses were “finance and insurance” (14.0%) and “services” (11.1%) among urban students, and “local government” (15.1%) among rural students.

- Regarding intended occupation, the proportions answering “undecided” and “no particular preference” were both lower in urban areas (15.5% and 6.7%, respectively) than in rural areas (25.0% and 10.9%). Conversely, “management/administrative planning” (16.7%) and “sales/marketing” (33.1%) were higher among urban students than among rural students (10.2% and 12.9%).

- Regarding place of origin, most urban university students were from urban areas (78.7%), while most rural university students were from rural areas (96.5%).

- Regarding preferred employment location, 89.5% of urban students expressed a preference for working in urban areas, while 82.6% of rural students preferred working in rural areas.

- Finally, regarding local orientation, narrow local orientation (preference for employment in the home prefecture) was 49.2% among urban students and 71.8% among rural students; broad local orientation (in an adjacent prefecture) was 19.7% and 8.6%, respectively; and urban orientation (in one of the three metropolitan areas excluding home and adjacent prefectures) was 23.8% and 13.7%, respectively.

2.2. Psychological Measures

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

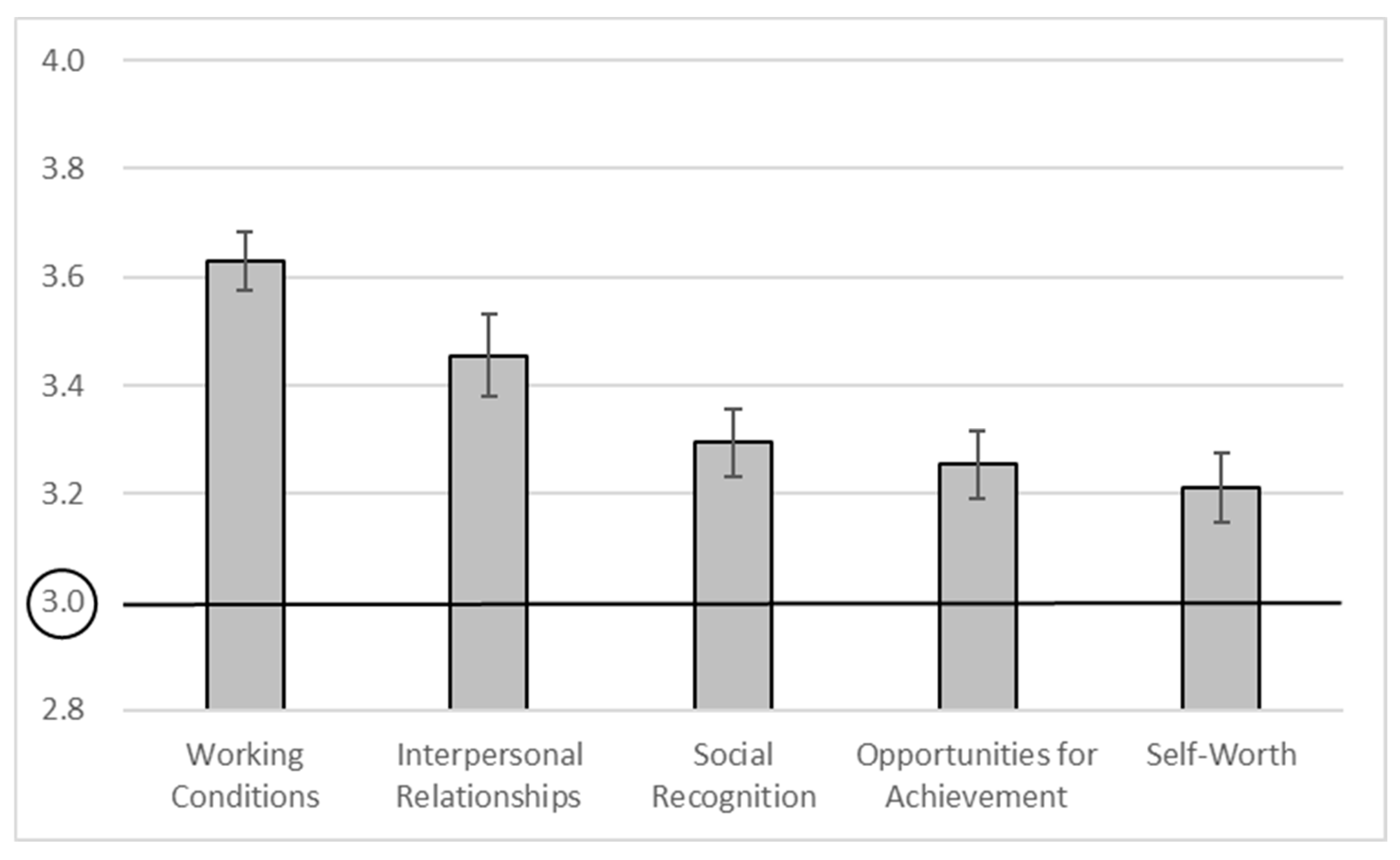

3.1. Overall Findings

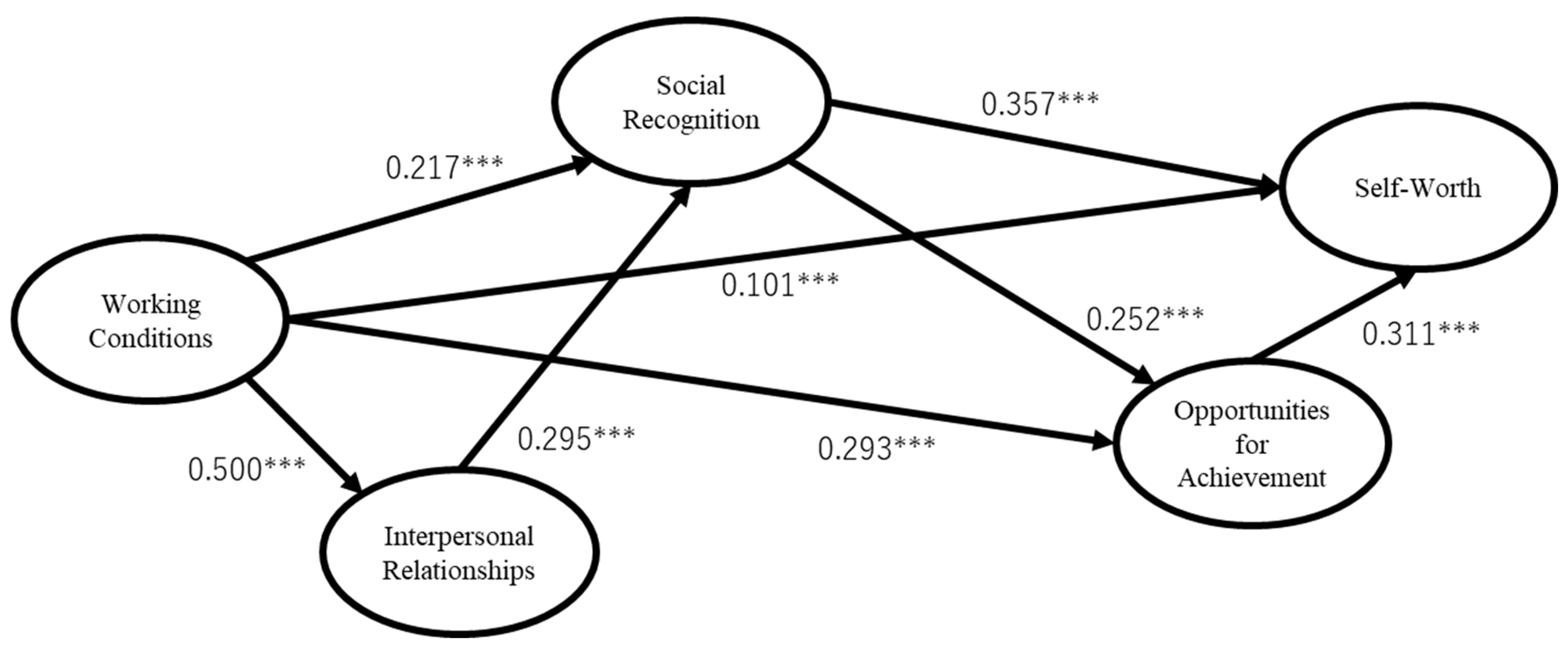

3.2. Path Analysis

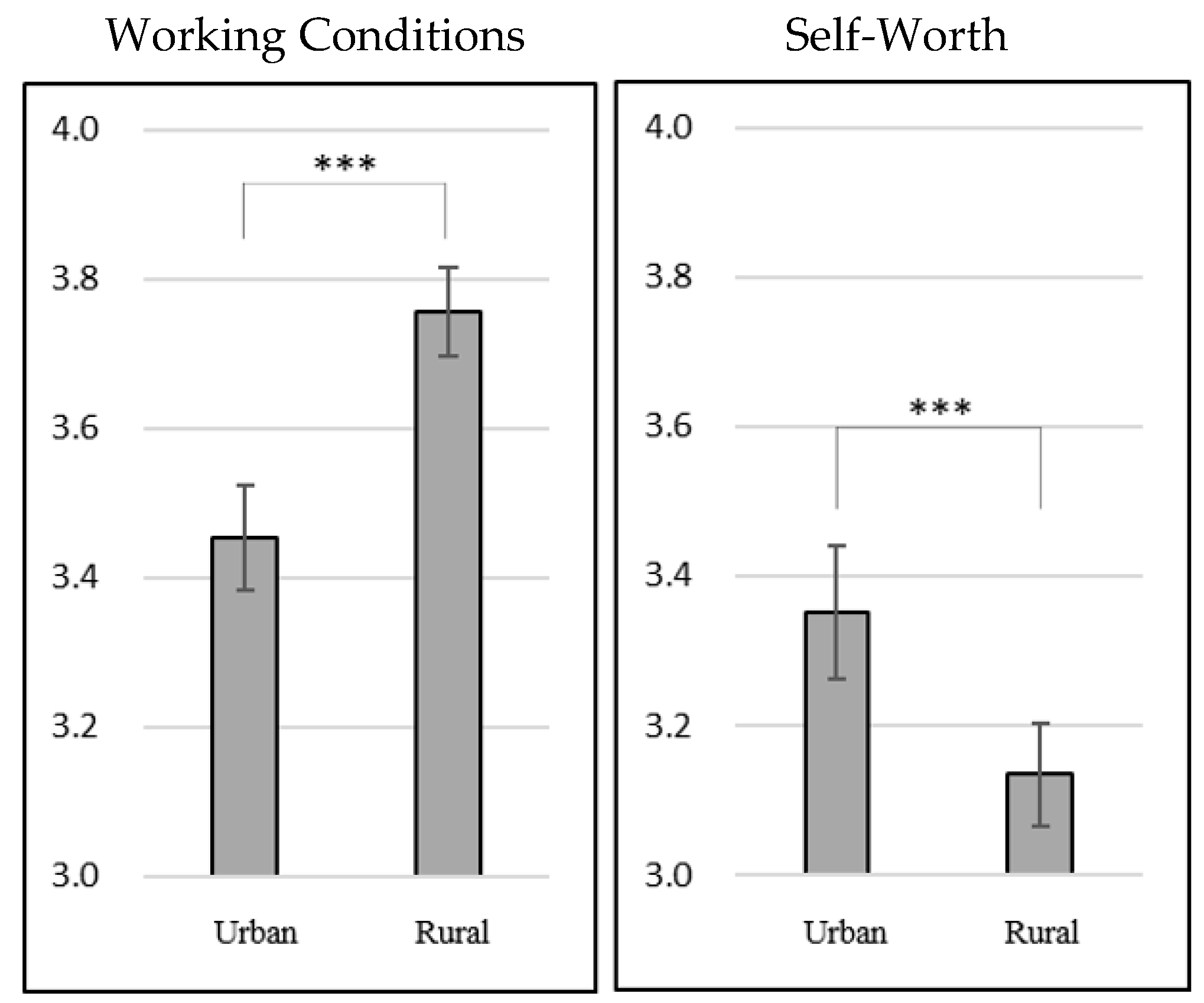

3.3. Changes in Occupational Values by University Location

3.4. Changes in Occupational Values by Gender and University Location

- For Working Conditions, both male and female students in rural universities scored higher than those in urban universities.

- For Self-Worth, both male and female students in urban universities scored higher than their counterparts in rural universities (although the difference was not significant among females).

- For Opportunities for Achievement, male students scored higher than female students regardless of university location (however, the difference between urban males and urban females was not significant).

- Emphasis on Working Conditions increased particularly among students in rural areas;

- Emphasis on Self-Worth increased particularly among students in urban areas;

- Emphasis on Opportunities for Achievement increased particularly among male students.

3.5. Changes in Occupational Values by Place of Origin and University Location

- For Working Conditions, students from rural areas who also attended urban universities (Rural → Rural) scored significantly higher than the other groups.

- For Self-Worth, students from urban areas who attended urban universities (Urban → Urban) scored higher than Rural → Rural students.

- Additionally, students from rural areas who attended urban universities (Rural → Urban) placed greater emphasis on Social Evaluation than did students from urban areas who attended rural universities (Urban → Rural) (details available upon request).

3.6. Analysis of Local and Urban Employment Orientation

3.7. Factors Enhancing Local Employment Orientation

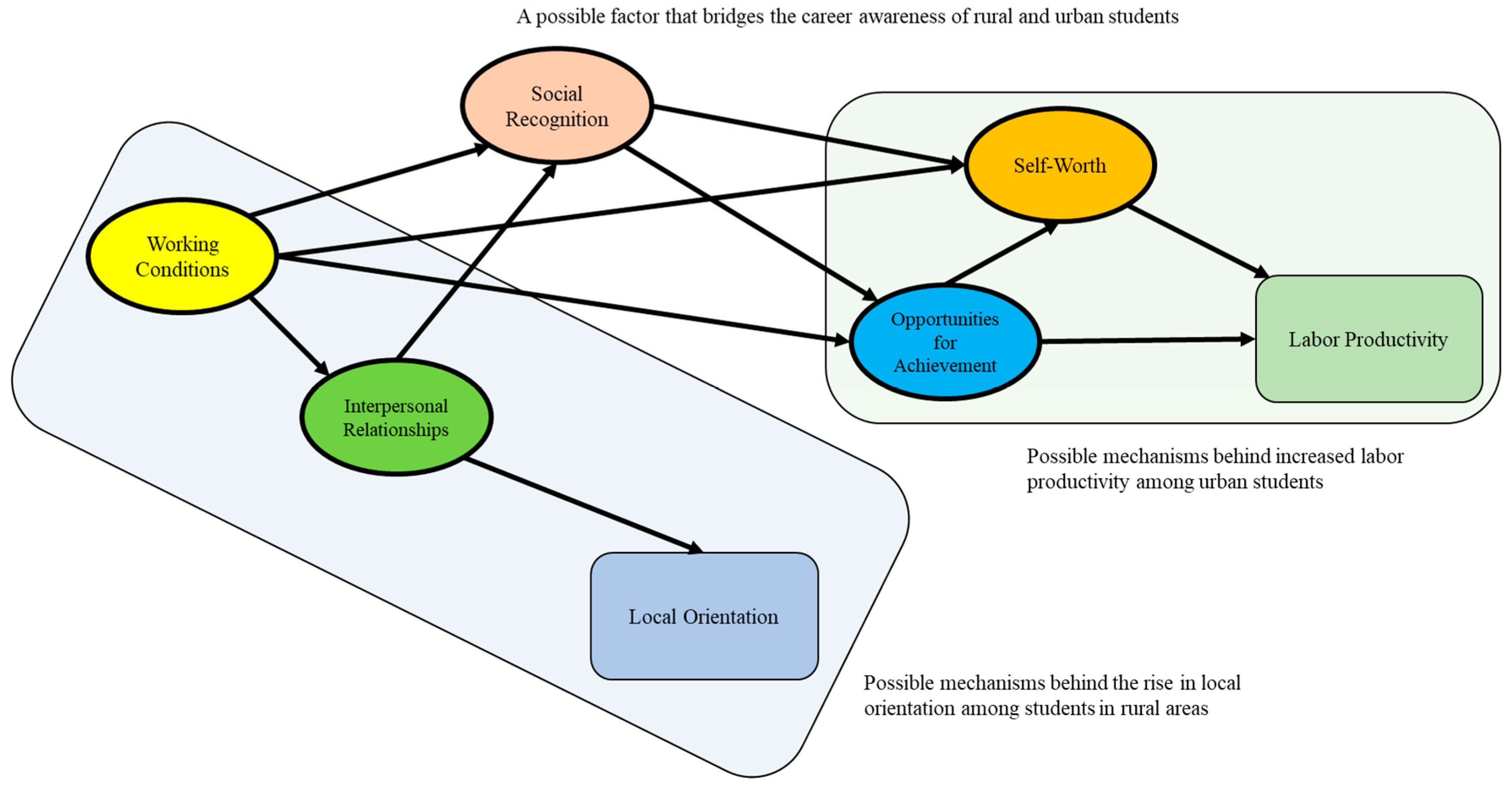

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings of the Present Study

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abe, N., Kitao, Y., & Narita, M. (2016). A study on recruitment activities of small and medium-sized enterprises in local cities: Based on a questionnaire survey of university students in the Chugoku, Shikoku, and Kyushu regions. Information Systems and Social Environment Research Report (IS), 2016(7), 1–8. Available online: https://ipsj.ixsq.nii.ac.jp/ej/?item_id=157912 (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Adachi, F. (2010). Current status and issues of telework: A study on home-based work and telecommuting. Kyoto Gakuen University Journal of Business Administration, 20(1), 49–70. Available online: http://id.nii.ac.jp/1455/00001042/ (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Aikebaier, S. (2024). COVID-19, new challenges to human safety: A global review. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1371238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabinet Office. (2020). Government of Japan. Survey on changes in living consciousness and behavior under the influence of COVID-19. Available online: https://www5.cao.go.jp/keizai2/wellbeing/covid/pdf/shiryo2.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese)

- Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNN. (2020, December 26). Medical school applications surge during the COVID-19 pandemic: The “Fauci effect”. Available online: https://www.cnn.co.jp/usa/35164444.html (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Cullinan, J., Flannery, D., Harold, J., Lyons, S., & Palcic, D. (2021). The disconnected: COVID-19 and disparities in access to quality broadband for higher education students. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DISCO Inc. (2021). Job hunting awareness survey as of February 1: Results of the CareerTasu Job Hunting 2022 student monitor survey. Available online: https://www.disc.co.jp/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/202102_gakuseichosa_k-.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Dohlman, L., DiMeglio, M., Hajj, J., & Laudanski, K. (2019). Global brain drain: How can the Maslow theory of motivation improve our understanding of physician migration? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE, 15(7), e0236337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Gibb, L. C., & Nielsen, K. (2014). Entrepreneurship within urban and rural areas: Creative people and social networks. Regional Studies, 48(1), 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, Y. (2003). Success factors of telework in Japan. Sogo Seisaku Kenkyu, (13), 25–40. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10236/8011 (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Furukawa, Y. (2010). Concerns and effects regarding telework: Results of a questionnaire survey. Sogo Seisaku Kenkyu, (35), 1–15. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10236/6581 (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Gakujo Co., Ltd. (2020, September). Comparison of awareness between 2022 graduating students and 20s job changers: Changes in preferred industries. (September 2020 ed.). Available online: https://prtimes.jp/main/html/rd/p/000000588.000013485.html (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (1997). Gender differences in the perception and use of e-mail: An extension to the technology acceptance model. MIS Quarterly, 21(4), 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1956). Fundamental statistics in psychology and education. McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- He, F. (2024). The impact of the implementation of state of emergency declarations and the spread of infections during the COVID-19 pandemic on employment. Journal of Personal Finance and Economics, 60, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikichi, H., Aoki, T., & Obuchi, K. (2009). Mechanisms of forming attachment to local communities: The effects of physical and social environments. Journal of Japan Society of Civil Engineers, D, 65(2), 101–110. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hioki, T. (2020, September 13). Reasons why the increase in “local-minded youth” cannot be welcomed uncritically: Choosing between “mental richness” and “economic prosperity”. Toyo Keizai Online. Available online: https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/361935 (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Hirao, M., & Shigematsu, M. (2006). Local orientation and employment consciousness among university students. University Education, 3, 161–168. Available online: https://petit.lib.yamaguchi-u.ac.jp/14498 (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Ishiguro, I. (2007). Factors influencing Aomori high school graduates’ decision to attend universities outside the prefecture: A comparison between in-prefecture and out-of-prefecture students. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 18, 69–79. Available online: https://hirosaki.repo.nii.ac.jp/?item_id=500 (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Iyo Bank Regional Economic Research Center. (2020, August 6). Survey on the attitudes of university students in Ehime Prefecture during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available online: http://www.iyoirc.jp/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/20-215.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Japan Finance Corporation Research Institute. (2015). The reality of small and medium-sized enterprises that support local employment and industry: A study of SMEs contributing significantly to job creation in regional areas. JFC Research Report, 2015-1. Available online: https://www.jfc.go.jp/n/findings/pdf/soukenrepo_15_06_09.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese)

- Jokura, R. (2018). Human resource policies promoting the spread of telework. Works Review, 13(2), 2–11. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S., Engelsted, L., Lei, X., & Lockwood, K. (2018). Unpackaging manager mistrust in allowing telework: Comparing and integrating theoretical perspectives. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(3), 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A. C., Meier, L. L., Gross, S., & Semmer, N. K. (2015). Gender differences in the association of a high quality job and self-esteem over time: A multiwave study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(1), 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A. I., Mejía-Rodríguez, A. M., & Strello, A. (2022). Inequality in remote learning quality during COVID-19: Student perspectives and mitigating factors. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 10(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T., Mullins, L. B., & Yoon, T. (2021). Supervision of telework: A key to organizational performance. The American Review of Public Administration, 51, 0275074021992058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubun, K., & Yasui, M. (2021). Gender differences in organizational commitment and rewards within Japanese manufacturing companies in China. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 28(3), 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoda, T. (2007). Relationship between occupational values and career choice behavior among university students. Japanese Journal of Adolescent Psychology, 18, 1–17. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jsyap/18/0/18_KJ00004556976/_article/-char/ja/ (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Koyama, O. (2017). Is global orientation incompatible with local career orientation? Journal of University Evaluation Research, 16, 87–97. Available online: https://www.juaa.or.jp/media/files/pdf/publication/evaluation/no_16/backnumber_14.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Kutsuwada, R. (2009). Local orientation and social inclusion/exclusion: A comparative case study of graduates from a private local university. In A. Higuchi (Ed.), Comparative analysis of youth issues: East Asian international comparison and domestic regional comparison (Vol. 3, pp. 151–170). Faculty of Sociology, Hosei University. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B. T. F., & Sims, J. P. (2023). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: A framework for understanding China’s soes, smes and Decentralisation. China Report, 59(4), 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., Urbano, D., & Guerrero, M. (2011). Regional variations in entrepreneurial cognitions: Start-up intentions of university students in Spain. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 23(3–4), 187–215. Available online: https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/70213/Regional_variations_in_entrepreneurial_cognitions.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Martin, X., Salomon, R. M., & Wu, Z. (2010). The institutional determinants of agglomeration: A study in the global semiconductor industry. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(6), 1769–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynavi. (2020a). Survey on job consciousness of 2021 university graduates. Available online: https://career-research.mynavi.jp/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/21_Uturn.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Mynavi. (2020b). Survey on U-turn and local employment among 2021 university graduates. Available online: https://career-research.mynavi.jp/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2021_shusyokuishiki.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- National Federation of University Co-operative Associations. (2020). Emergency survey for university and graduate students: Summary of results. Available online: https://ksnet.u-coop.net/2020/05/ce4d15100e61c45b282591b6124794d15ab15939.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Ogata, M. (2011). An empirical study on university students’ occupational orientation: From a questionnaire survey of job-seeking students. Konan Business Review, 52(2), 51–81. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsali, M. E., Mousa, D. P. V., Papadopoulou, E. V., Papadopoulou, K. K., Kaparounaki, C. K., Diakogiannis, I., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2020). University students’ changes in mental health status and determinants of behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small and Medium Enterprise Agency. (2017). Employment situation and labor shortages in SMEs. White paper on small and medium enterprises in Japan 2017, part 1, chapter 3. Available online: https://www.chusho.meti.go.jp/pamflet/hakusyo/H29/PDF/h29_pdf_mokujityuu.html (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese)

- Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, S. (2012). Local orientation and career development among university students. Humanities Research, 123, 123–140. Available online: https://barrel.repo.nii.ac.jp/?item_id=574 (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Tannen, D. (1994). Gender and discourse. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ushirokawa, M. (2019). Trends and determinants of interregional mobility among young people: Inter-prefectural mobility at university entrance and first employment. Kyoto Sangyo University Economic Review, 6, 1–42. Available online: https://ksu.repo.nii.ac.jp/?item_id=10249 (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- von Proff, S., Duschl, M., & Brenner, T. (2017). Motives behind the mobility of university graduates–A study of three German universities. Review of Regional Research, 37(1), 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1), 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthley, R., MacNab, B., Brislin, R., Ito, K., & Rose, E. L. (2009). Workforce motivation in Japan: An examination of gender differences and management perceptions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(7), 1503–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, N. (2012). Within-culture variations of collectivism in Japan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(8), 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonehara, T., & Tanaka, D. (2015). Relationship between local orientation and psychological characteristics: Toward the construction of a new developmental model. Regional Studies, Faculty of Regional Sciences, Tottori University, 11(3), 139–151. Available online: https://repository.lib.tottori-u.ac.jp/records/222 (accessed on 20 March 2021). (In Japanese).

- Zhao, L., Cao, C., Li, Y., & Li, Y. (2022). Determinants of the digital outcome divide in E-learning between rural and urban students: Empirical evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic based on capital theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 130, 107177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S., & Yan, Y. (2024). Changes in employment psychology of Chinese university students during the two stages of COVID-19 control and their impacts on their employment intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1447103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Urban | Rural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 207 | 165 | |

| Female | 42 | 102 | |

| Year in University | |||

| First-year student | 41 | 10 | |

| Second-year student | 7 | 150 | |

| Third-year student | 150 | 80 | |

| Fourth-year student | 51 | 27 | |

| Preferred Type of Employment after Graduation | |||

| Work for a large enterprise | 86 | 26 | |

| Work for a small or venture company | 60 | 115 | |

| Work as a public servant | 10 | 56 | |

| Take over or help with family business | 4 | 2 | |

| Not decided yet | 77 | 57 | |

| Other | 9 | 5 | |

| Preferred Industry after Graduation | |||

| Agriculture, forestry, fisheries, or mining | 1 | 2 | |

| Construction | 6 | 7 | |

| Manufacturing | 11 | 20 | |

| Electricity, gas, heat supply, or water | 3 | 1 | |

| Information and communication | 16 | 12 | |

| Transportation or postal services | 5 | 1 | |

| Wholesale or retail trade | 16 | 16 | |

| Finance or insurance | 34 | 19 | |

| Real estate or leasing | 15 | 7 | |

| Academic research, professional, or technical services | 4 | 3 | |

| Service industry | 27 | 14 | |

| Education or learning support | 3 | 5 | |

| Medical or welfare services | 2 | 2 | |

| National government employee (excluding educational positions) | 3 | 7 | |

| Local government employee (excluding educational positions) | 6 | 39 | |

| Enter graduate school | 1 | 2 | |

| Not decided yet | 59 | 66 | |

| No particular preference for industry | 24 | 33 | |

| Other (please specify) | 7 | 2 | |

| Preferred Occupation after Graduation | |||

| Management or business planning | 40 | 26 | |

| Sales or marketing | 79 | 33 | |

| Basic or technical research | 1 | 0 | |

| Engineering or product design | 5 | 1 | |

| Product planning or development | 17 | 21 | |

| Purchasing or procurement | 1 | 0 | |

| Manufacturing, production, or quality control | 3 | 11 | |

| Research, advertising, or promotion | 8 | 9 | |

| Information systems or IT development | 6 | 4 | |

| Logistics or distribution | 3 | 1 | |

| Public relations or editing | 3 | 18 | |

| Human resources, general affairs, or accounting | 11 | 23 | |

| Enter graduate school | 3 | 3 | |

| Not decided yet | 37 | 64 | |

| No particular preference for occupation | 16 | 28 | |

| Other (please specify) | 6 | 14 | |

| Place of Origin | |||

| Urban area | 196 | 8 | |

| Rural area | 51 | 249 | |

| Overseas | 2 | 1 | |

| Relationship between Place of Origin and University Location | |||

| Same as university location | 112 | 208 | |

| Different from university location | 134 | 50 | |

| Preferred Employment Location | |||

| Urban area | 213 | 42 | |

| Rural area | 20 | 213 | |

| Overseas | 5 | 3 | |

| Orientation toward Local or Urban Employment | |||

| Narrow local orientation (prefers employment within home prefecture) | 120 | 183 | |

| Broad local orientation (prefers employment within home or neighboring prefecture) | 48 | 22 | |

| Urban orientation (prefers employment in metropolitan areas) | 58 | 35 | |

| Other | 18 | 15 | |

| Factor 1: Working Conditions | Factor 2: Interpersonal Relationships | Factor 3: Self-Worth | Factor 4: Social Recognition | Factor 5: Opportunities for Achievement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working hours are flexible (e.g., flextime system). | 0.631 | 0.042 | 0.072 | 0.085 | 0.177 |

| A stable income can be obtained. | 0.596 | 0.211 | 0.078 | 0.117 | −0.054 |

| Employee benefits are well provided. | 0.594 | 0.203 | 0.099 | 0.064 | 0.146 |

| Paid vacation days are sufficient. | 0.583 | 0.155 | 0.144 | 0.030 | 0.020 |

| There are few job transfers. | 0.543 | 0.199 | 0.109 | 0.104 | −0.047 |

| Overtime work is limited. | 0.541 | 0.176 | 0.155 | 0.052 | 0.016 |

| Remote work is available. | 0.540 | −0.100 | −0.002 | 0.037 | 0.280 |

| The workplace is located in my hometown. | 0.507 | 0.136 | −0.042 | 0.217 | 0.095 |

| The workplace is conveniently accessible. | 0.429 | 0.226 | 0.045 | 0.075 | 0.097 |

| Side jobs are permitted. | 0.423 | −0.063 | 0.001 | −0.039 | 0.357 |

| I can build a good atmosphere with my colleagues. | 0.229 | 0.868 | 0.117 | 0.116 | 0.083 |

| I can establish mutual trust with people at the workplace. | 0.203 | 0.807 | 0.088 | 0.137 | 0.064 |

| I can feel connected to others through my work. | 0.253 | 0.791 | 0.107 | 0.183 | 0.083 |

| I am accepted by people around me at work. | 0.304 | 0.742 | 0.134 | 0.179 | 0.072 |

| I can engage in work that expands my potential. | 0.122 | 0.035 | 0.768 | 0.110 | 0.193 |

| I can engage in work that makes use of my individuality. | 0.087 | 0.126 | 0.745 | 0.142 | 0.137 |

| I can engage in work that utilizes my abilities. | 0.147 | 0.057 | 0.707 | 0.162 | 0.070 |

| I can engage in work that contributes to my personal growth. | 0.064 | 0.067 | 0.657 | 0.275 | 0.227 |

| I can engage in work that gives me a sense of fulfillment. | 0.072 | 0.188 | 0.616 | 0.264 | 0.217 |

| I can engage in work that is recognized by society. | 0.120 | 0.164 | 0.277 | 0.759 | 0.107 |

| I can engage in work that earns respect from others. | 0.170 | 0.113 | 0.153 | 0.738 | 0.136 |

| I can engage in work that is highly valued by the public. | 0.127 | 0.069 | 0.262 | 0.679 | 0.039 |

| I can engage in work that contributes to society. | 0.094 | 0.227 | 0.166 | 0.563 | 0.129 |

| I can become independent in the future. | 0.066 | −0.019 | 0.177 | 0.054 | 0.765 |

| I have opportunities to start my own business. | 0.120 | 0.088 | 0.244 | 0.110 | 0.757 |

| I can gain experience in a wide variety of jobs. | 0.145 | 0.185 | 0.163 | 0.167 | 0.601 |

| I can make use of new ideas that I have conceived. | 0.173 | 0.155 | 0.304 | 0.187 | 0.489 |

| Mean | SD | 95%CI Lower | 95%CI Upper | Working Conditions | Interpersonal Relationships | Social Recognition | Opportunities for Achievement | Self-Worth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working Conditions | 3.628 | 0.535 | 3.575 | 3.681 | (0.814) | ||||

| Interpersonal Relationships | 3.454 | 0.752 | 3.380 | 3.529 | 0.460 ** | (0.910) | |||

| Social Recognition | 3.294 | 0.614 | 3.233 | 3.355 | 0.282 ** | 0.305 ** | (0.841) | ||

| Opportunities for Achievement | 3.254 | 0.618 | 3.193 | 3.315 | 0.312 ** | 0.263 ** | 0.319 ** | (0.773) | |

| Self-Worth | 3.212 | 0.636 | 3.149 | 3.274 | 0.164 ** | 0.248 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.440 ** | (0.855) |

| Urban | Rural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | ||

| Working Conditions | 3.45 | 0.564 | 3.75 | 0.463 | −6.385 | *** |

| Interpersonal Relationships | 3.47 | 0.833 | 3.44 | 0.697 | 0.366 | |

| Social Recognition | 3.30 | 0.683 | 3.27 | 0.564 | 0.584 | |

| Opportunities for Achievement | 3.31 | 0.712 | 3.24 | 0.549 | 1.208 | |

| Self-Worth | 3.35 | 0.708 | 3.13 | 0.549 | 3.749 | *** |

| Frequency | 245 | 255 | ||||

| Male × Urban | Male × Rural | Female × Urban | Female × Rural | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | ||

| Working Conditions | 3.45 | 0.562 | 3.77 | 0.467 | 3.48 | 0.576 | 3.72 | 0.457 | 13.663 | *** |

| Interpersonal Relationships | 3.45 | 0.821 | 3.49 | 0.696 | 3.57 | 0.891 | 3.38 | 0.697 | 0.711 | |

| Social Recognition | 3.32 | 0.696 | 3.33 | 0.594 | 3.21 | 0.611 | 3.17 | 0.500 | 1.857 | |

| Opportunities for Achievement | 3.35 | 0.715 | 3.32 | 0.566 | 3.15 | 0.681 | 3.13 | 0.504 | 3.562 | ** |

| Self-Worth | 3.36 | 0.710 | 3.17 | 0.558 | 3.31 | 0.704 | 3.08 | 0.536 | 5.093 | *** |

| Frequency | 202 | 154 | 42 | 101 | ||||||

| Urban → Urban | Urban → Rural | Rural → Urban | Rural → Rural | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | ||

| Working Conditions | 3.45 | 0.554 | 3.29 | 0.422 | 3.45 | 0.604 | 3.76 | 0.459 | 14.816 | *** |

| Interpersonal Relationships | 3.49 | 0.801 | 3.03 | 0.920 | 3.38 | 0.963 | 3.45 | 0.687 | 1.052 | |

| Social Recognition | 3.28 | 0.681 | 2.84 | 0.481 | 3.44 | 0.669 | 3.28 | 0.564 | 2.287 | * |

| Opportunities for Achievement | 3.27 | 0.695 | 2.93 | 0.773 | 3.44 | 0.749 | 3.24 | 0.541 | 2.068 | |

| Self-Worth | 3.34 | 0.698 | 3.33 | 0.595 | 3.37 | 0.760 | 3.13 | 0.552 | 4.637 | *** |

| Frequency | 194 | 8 | 49 | 238 | ||||||

| Urban → Urban | Urban → Rural | Rural → Urban | Rural → Rural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow local | 108 | 6 | 11 | 176 |

| orientation | 55.10% | 75.00% | 23.90% | 71.50% |

| Broad local | 44 | 0 | 4 | 22 |

| orientation | 22.40% | 0.00% | 8.70% | 8.90% |

| Urban | 29 | 0 | 28 | 35 |

| orientation | 14.80% | 0.00% | 60.90% | 14.20% |

| Others | 15 | 2 | 3 | 13 |

| 7.70% | 25.00% | 6.50% | 5.30% | |

| χ2= | 87.605 *** | |||

| Coefficient (B) | Standard Error (SE) | Odds Ratio (Exp(B)) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.615 | 1.281 | 0.541 | 0.044 | ~ | 6.660 | 0.631 |

| Male a | 0.573 | 0.356 | 1.770 | 0.884 | ~ | 3.560 | 0.107 |

| Work for a large company b | −0.903 | 0.533 | 0.406 | 0.143 | ~ | 1.150 | 0.090 * |

| Work for a small or venture company b | 0.871 | 0.399 | 2.390 | 1.090 | ~ | 5.220 | 0.029 ** |

| Real estate/goods rental industry c | 1.651 | 1.255 | 5.210 | 0.445 | ~ | 61.000 | 0.188 |

| Local government official (excluding teachers) c | 1.203 | 0.629 | 3.330 | 0.971 | ~ | 11.400 | 0.056 * |

| Management/administrative planning d | 1.100 | 0.675 | 3.000 | 0.800 | ~ | 11.300 | 0.103 |

| Research/advertising/public relations d | −1.469 | 0.985 | 0.230 | 0.033 | ~ | 1.590 | 0.136 |

| Public relations/editing d | 1.597 | 1.090 | 4.940 | 0.584 | ~ | 41.800 | 0.143 |

| Human relations e | 0.698 | 0.284 | 2.010 | 1.150 | ~ | 3.510 | 0.014 ** |

| Opportunities for achievement e | −0.542 | 0.342 | 0.582 | 0.298 | ~ | 1.140 | 0.113 |

| Coefficient (B) | Standard Error (SE) | Odds Ratio (Exp(B)) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.952 | 1.194 | 0.052 | 0.005 | ~ | 0.542 | 0.013 ** |

| Third-year student f | 1.230 | 0.527 | 3.420 | 1.220 | ~ | 9.610 | 0.020 ** |

| Work for a large company b | −0.959 | 0.570 | 0.383 | 0.125 | ~ | 1.170 | 0.092 * |

| Work for a small or venture company b | 1.043 | 0.486 | 2.840 | 1.090 | ~ | 7.350 | 0.032 ** |

| Finance/Insurance industry c | −1.114 | 0.699 | 0.328 | 0.083 | ~ | 1.290 | 0.111 |

| National government employee (excluding educational positions) c | 1.751 | 1.315 | 5.760 | 0.438 | ~ | 75.700 | 0.183 |

| Local government employee (excluding educational positions) c | 0.995 | 0.733 | 2.710 | 0.643 | ~ | 11.400 | 0.175 |

| Management/Business planning d | 2.120 | 1.089 | 8.330 | 0.985 | ~ | 70.400 | 0.052 * |

| Research/Advertising/Promotion d | −1.654 | 1.092 | 0.191 | 0.023 | ~ | 1.630 | 0.130 |

| Public relations/Editing d | 1.472 | 1.153 | 4.360 | 0.455 | ~ | 41.700 | 0.202 |

| No particular preference for occupation d | 1.304 | 0.852 | 3.680 | 0.693 | ~ | 19.600 | 0.126 |

| Human relations e | 1.048 | 0.342 | 2.850 | 1.460 | ~ | 5.580 | 0.002 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kokubun, K. During the COVID-19 Pandemic, the Gap in Career Awareness Between Urban and Rural Students Widened. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040103

Kokubun K. During the COVID-19 Pandemic, the Gap in Career Awareness Between Urban and Rural Students Widened. Psychology International. 2025; 7(4):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040103

Chicago/Turabian StyleKokubun, Keisuke. 2025. "During the COVID-19 Pandemic, the Gap in Career Awareness Between Urban and Rural Students Widened" Psychology International 7, no. 4: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040103

APA StyleKokubun, K. (2025). During the COVID-19 Pandemic, the Gap in Career Awareness Between Urban and Rural Students Widened. Psychology International, 7(4), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7040103