Positive Mental Health: Psychometric Evaluation of the PMHI-19 in a Sample of University Student-Athletes and Dancers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrumentation

2.1.1. Positive Mental Health Instrument Short Form

2.1.2. Demographic Questionnaire

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

2.2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

2.2.3. Covariance Model

3. Results

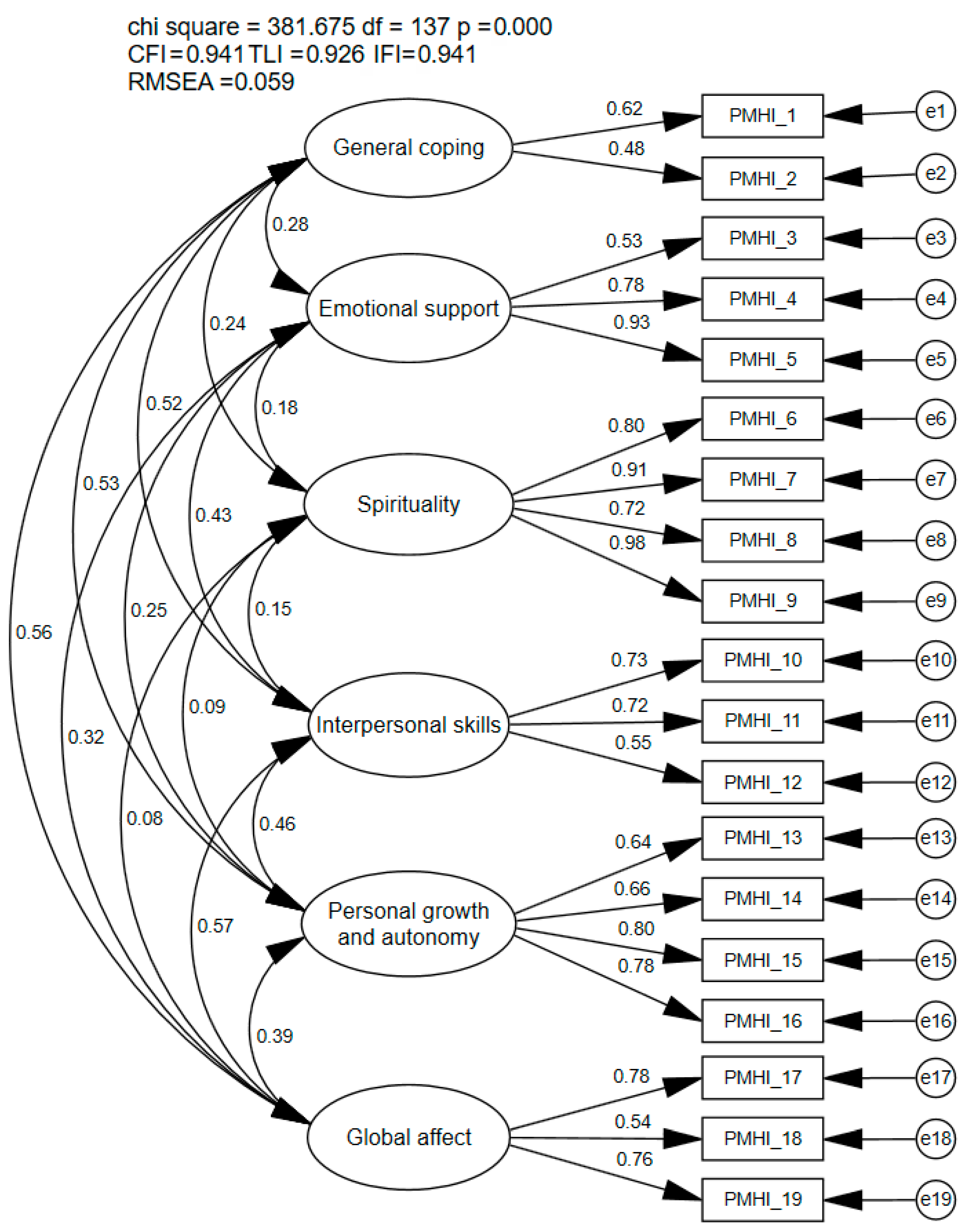

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.3. Covariance Models

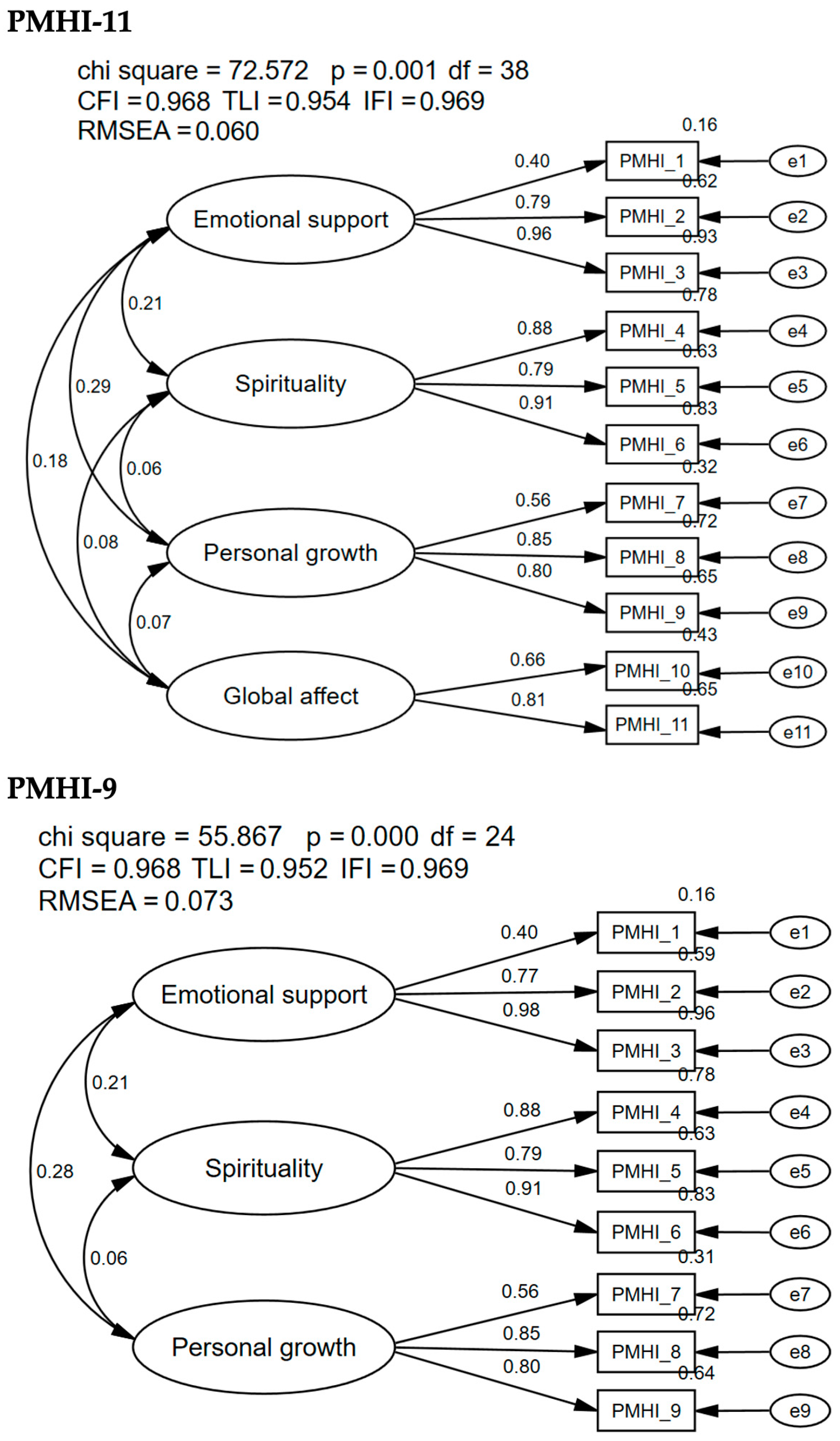

3.3.1. PMHI-11

3.3.2. PMHI-9

4. Discussion

Future Research and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMH | Positive mental health |

| PMHI | Positive Mental Health Instrument |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| IFI | Bollen’s incremental fit index |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

References

- Bailen, N. H., Green, L. M., & Thompson, R. J. (2019). Understanding emotion in adolescents: A review of emotional frequency, intensity, instability, and clarity. Emotion Review, 11(1), 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, B. W., & Redmond, C. J. (2017). Psychology of sport injury. Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, M. P., Nelson, M. C., Pickering, M. A., Appleby, K. M., Grindley, E. J., Larkins, L. W., & Baker, R. T. (2021). Measuring psychological pain: Psychometric analysis of the Orbach and Mikulincer Mental Pain Scale. Measurement Instruments for the Social Sciences, 3(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, B., Gavrilova, Y., Galante, M., Gavrilova, E., Loughran, T., Scott, J., Chow, G., Plant, C. P., & Allen, D. N. (2018). Controlled evaluation of an optimization approach to mental health and sport performance. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 12(2), 234–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohls, J. K., König, H.-H., Quirke, E., & Hajek, A. (2021). Anxiety, depression and quality of life—A systematic review of evidence from longitudinal observational studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iasiello, M., Van Agteren, J., Keyes, C. L. M., & Cochrane, E. M. (2019). Positive mental health as a predictor of recovery from mental illness. Journal of Affective Disorders, 251, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L., & Zenko, Z. (2021). Strategies to facilitate more pleasant exercise experiences. In Z. Zenko, & L. Jones (Eds.), Essentials of exercise and sport psychology: An open access textbook (pp. 242–270). Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M., Meijen, C., McCarthy, P. J., & Sheffield, D. (2009). A theory of challenge and Threat States in Athletes. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2(2), 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S., & Kahn, R. A. (2017). Chronic stress leads to anxiety and depression. Annals of Psychiatry and Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. L. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Methodology in the social sciences. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Knettel, B. A., Cherenack, E. M., Rougier-Chapman, C., & Bianchi-Rossi, C. (2023). Examining associations of coping strategies with stress, alcohol, and substance use among college athletes: Implications for improving athlete coping. Journal of Intercollegiate Sport, 16(2), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, S. M. A., Westerhof, G. J., Bohlmeijer, E. T., Ten Klooster, P. M., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2011). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, C. E., Butts, M. M., & Michels, L. C. (2006). The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria: What did they really say? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluch-Canut, T., Puig-Llobet, M., Sánchez-Ortega, A., Roldán-Merino, J., & Ferré-Grau, C. (2013). Assessing positive mental health in people with chronic physical health problems: Correlations with socio-demographic variables and physical health status. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukat, J., Margraf, J., Lutz, R., Van Der Veld, W. M., & Becker, E. S. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Positive Mental Health Scale (PMH-scale). BMC Psychology, 4(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCAA. (2023). Current findings on student-athlete mental health (NCAA student-athlete health and wellness study). Available online: https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/wellness/Dec2023RES_HW-MentalHealthRelease.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Pesudovs, K., Burr, J. M., Harley, C., & Elliott, D. B. (2007). The development, assessment, and selection of questionnaires. Optometry and Vision Science, 84(8), 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, C., Carvalho, J. C., Gonçalves, A., Nogueira, M. J., Lluch-Canut, T., & Roldán-Merino, J. (2020). Levels of positive mental health in Portuguese and Spanish nursing students. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 26(5), 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Vaingankar, J. A., Abdin, E., Chong, S. A., Sambasivam, R., Jeyagurunathan, A., Seow, E., Picco, L., Pang, S., Lim, S., & Subramaniam, M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the positive mental health instrument among people with mental disorders: A cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaingankar, J. A., Abdin, E., Van Dam, R. M., Chong, S. A., Tan, L. W. L., Sambasivam, R., Seow, E., Chua, B. Y., Wee, H. L., Lim, W. Y., & Subramaniam, M. (2020). Development and validation of the Rapid Positive Mental Health Instrument (R-PMHI) for measuring mental health outcomes in the population. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaingankar, J. A., Subramaniam, M., Abdin, E., Picco, L., Chua, B. Y., Eng, G. K., Sambasivam, R., Shafie, S., Zhang, Y., & Chong, S. A. (2014). Development, validity and reliability of the short multidimensional positive mental health instrument. Quality of Life Research, 23(5), 1459–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaingankar, J., Subramaniam, M., Chong, S. A., Abdin, E., Orlando Edelen, M., Picco, L., Lim, Y. W., Phua, M. Y., Chua, B. Y., Tee, J. Y., & Sherbourne, C. (2011). The positive mental health instrument: Development and validation of a culturally relevant scale in a multi-ethnic asian population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(1), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vani, M., Murray, R., & Sabiston, C. (2021). Body image and physical activity. Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (1998). Wellbeing measures in primary health care/the DepCare Project (No. WHO/EURO: 1998-4234-43993-62027). Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2022, June 17). Mental health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Yusko, D. A., Buckman, J. F., White, H. R., & Pandina, R. J. (2008). Alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, and performance enhancers: A comparison of use by college student athletes and nonathletes. Journal of American College Health, 57(3), 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 99 | 19.7 |

| Female | 404 | 80.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 391 | 77.7 |

| African | 61 | 12.1 |

| American | 46 | 9.1 |

| Hispanic | 17 | 3.4 |

| Asian | 7 | 1.4 |

| Athlete status | ||

| Student-athlete | 219 | 43.5 |

| Dancer | 284 | 56.5 |

| Injury status | ||

| Healthy | 372 | 74.0 |

| Acute injury | 19 | 3.8 |

| Sub-acute injury | 24 | 4.8 |

| Persistent injury | 82 | 16.3 |

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMHI_24R | 0.989 | |||

| PMHI_22R | 0.517 | |||

| PMHI_4 | 0.908 | |||

| PMHI_16 | 0.894 | |||

| PMHI_5 | 0.760 | |||

| PMHI_10 | 0.993 | |||

| PMHI_9 | 0.751 | |||

| PMHI_7 | 0.453 | |||

| PMHI_20 | 0.932 | |||

| PMHI_21 | 0.711 | |||

| PMHI_19 | 0.515 | |||

| Eigenvalue | 3.20 | 2.24 | 1.54 | 1.13 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.665 | 0.890 | 0.766 | 0.744 |

| Omega | - | 0.894 | 0.821 | 0.771 |

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMHI_4 | 0.909 | ||

| PMHI_16 | 0.895 | ||

| PMHI_15 | 0.760 | ||

| PMHI_10 | 0.939 | ||

| PMHI_9 | 0.804 | ||

| PMHI_7 | 0.469 | ||

| PMHI_20 | 0.933 | ||

| PMHI_21 | 0.707 | ||

| PMHI_19 | 0.522 | ||

| Eigenvalue | 2.90 | 2.21 | 1.50 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.890 | 0.766 | 0.744 |

| Omega | 0.894 | 0.821 | 0.771 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hansen-Oja, M.; Dluzniewski, A.; Baker, R.T.; Casanova, M.P. Positive Mental Health: Psychometric Evaluation of the PMHI-19 in a Sample of University Student-Athletes and Dancers. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7010015

Hansen-Oja M, Dluzniewski A, Baker RT, Casanova MP. Positive Mental Health: Psychometric Evaluation of the PMHI-19 in a Sample of University Student-Athletes and Dancers. Psychology International. 2025; 7(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleHansen-Oja, Morgan, Alexandra Dluzniewski, Russell T. Baker, and Madeline P. Casanova. 2025. "Positive Mental Health: Psychometric Evaluation of the PMHI-19 in a Sample of University Student-Athletes and Dancers" Psychology International 7, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7010015

APA StyleHansen-Oja, M., Dluzniewski, A., Baker, R. T., & Casanova, M. P. (2025). Positive Mental Health: Psychometric Evaluation of the PMHI-19 in a Sample of University Student-Athletes and Dancers. Psychology International, 7(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7010015