Abstract

From 31 August 2022 to early 2024, the City of Chicago welcomed nearly 40,000 migrants. Chicago had designated itself as a sanctuary city nearly 40 years ago and has since been a popular destination for migrants, accepting large numbers in other periods throughout its history. However, the influx during the period 2022–2024 was unique because of the large amounts of resources local and federal governments dedicated to settling these individuals. Immigrant benefits varied over this period but peaked at $15,000 per family, which did not include services offered by local churches and private organizations. In this study, log-linear multiple regression was employed to determine the impact subsidies can have on the local rental real estate market. According to the study findings, rental real estate rates increased by up to 5.6% in response to subsidization of migrant housing. Additionally, neighborhoods that were adjacent to migrant shelters experienced the greatest additional increase of 29.96%. In addition to the rapidity with which rental real estate pricing can respond to subsidies and policy shifts, the study findings demonstrate the financial benefits that can accrue to real estate owners and managers who participate in the rental marketplace with subsidization.

1. Introduction

Located in Illinois, Chicago is a major global city and the third most populous city in the United States, followed only by New York City and Los Angeles. Situated in the Midwest, it was the undisputed railroad center during the first half of the 20th century. Today, it is still considered a major transportation hub due to its proximity to Lake Michigan, the size of its airports, which are the third largest in the country, and a highway structure that enables its intermodal network. Chicago has considered itself a sanctuary city since 7 March 1985, when Mayor Harold Washington issued an executive order to that effect [1,2]. Mayor Richard M. Daley reissued this order on 25 April 1989, which remained in place until 2012, when the Chicago City Council ratified it into law in what came to be known as the ‘Welcoming City’ ordinance. Today, the city interprets the Welcoming City Ordinance to mean that individuals will not be asked about their immigration status, that information about them will not be disclosed to authorities, and, most important to this study, that city services will not be denied based on immigration status. To solidify even more sanctuary city benefits, Governor Pritzker signed Senate Bill 1817, which took effect on 1 January 2024; it added protections that prevent discrimination by housing providers on the basis of immigration status and extended the ability of undocumented immigrants to receive state drivers licenses [3].

The city of Chicago welcomed nearly 40,000 migrants from 31 August 2022 to early 2024. This influx began when Texas Gov. Greg Abbott sent the first two busloads of migrants to Union Station on 31 August 2022 [4]. This 40,000 does not represent the total number of migrants that entered the city during this period and includes only those individuals’ seeking asylum, having arrived from Texas via buses and airplanes. While Chicago had welcomed many migrants during other times in its history, such as the 41,000 that had immigrated in 2000, this more recent period, beginning in 2022, was unique because of the resources that local and federal governments expended in settling immigrant families.

Initially, these immigrant families were eligible to receive six months of rental assistance (capped at $15,000) and home furnishings. However, as time progressed, rental assistance was limited to three months for migrants who had arrived at the city’s shelters prior to 17 November 2023. Those that arrived after did not qualify for rental assistance but were nonetheless eligible for local services because of the Welcoming City ordinance. By the close of 2024, Federal, state, and city expenditures had reached $53.5 million, the majority of which had been allocated for rental assistance. Rental assistance funds from the American Rescue Plan Act were set to expire on 30 September 2025. In Chicago, an additional $4 million was available from the Chicago Department of Housing, and the Cook County Board approved up to $70 million to reimburse the city for providing asylum seekers housing, food, and other services [4,5]. To be eligible for rental assistance, asylum seekers must have lived in city or state intermediate housing, such as city shelters or state-run hotels. Applicants were also subject to the income requirement of making 80% or less than the area median income, although applicants did not need any income or employment to apply [6].

While many view these actions and expenditures positively, many others believe that this assistance was not fair to those immigrants to the U.S. who had spent years working, paying taxes, and raising a family [7,8]. In fact, in addition to the financial aid provided to these new asylum seekers, they also often received temporary protection status (TPS), which allowed them to live and work in the U.S. legally, benefits that increased the favorability of this group of asylum seekers to both employers and landlords relative to the immigrants who had preceded them. Even more broadly, non-migrant residents expressed cynicism while watching local governments spend hundreds of millions of dollars on migrants while giving locals in need mere “leftovers” [8,9].

The unique nature and factors surrounding this current group of migrants, including the benefits they received, presented me with an opportunity to examine the impact well-resourced migrants can have on the rental market. The proprietary data utilized in this study includes both date and apartment-level data that allow the examination of rental prices, which enables the answering of the following key questions relevant to the relationship between migrants and the rental real estate market:

- Does the location of a rental with respect to a migrant shelter influence its pricing in the rental real estate market?

- Does the existence of rental subsidies and the levels of assistance available to migrants impact the rental real estate market?

- Does the rental real estate market respond to policy changes at the city level?

- Which apartment characteristics tend to have the greatest impact on rental prices?

The following literature review focuses primarily on the impact of migrants on housing prices using broad market indicators. This focus results from the limited research conducted to date on the rental market and on the limitations of publicly available data.

2. Literature Review

Academic research has focused on the impact of immigration on real estate housing prices but has awarded less attention to the rental real estate market. For example, Accetturo et al. [10] examined 20 Italian cities and found that immigration raises average housing prices at the city level, a pattern that they showed as not carrying through at the district level due to the natives’ flight from immigrant-dense districts. The results of Gopy and Seetanah [11], who examined housing prices for eight Australian states on a quarterly basis from 2014 to 2017, indicated that immigration had a positive impact on housing prices, but only in some states did this produce a long-term positive effect. Having examined housing prices in New Zealand, Chong [12] found not only substantial appreciation following the Global Financial Crisis but also a 0.3% increase in the housing index for every 1% increase in number of immigrants. Similarly, Adams and Blickle [13] from the Swiss Institute found that increased immigration had a positive impact on house prices. More specifically, immigrants arriving from Western Europe or OECD countries resulted in a 1.15% increase in house prices, whereas those from the rest of the world resulted in only a 0.37% impact. Finally, upon examining the impact of immigration on house prices in 14 destination countries, Larkin et al. [14] found that, in general, increased house prices were associated with increased levels of immigration but that this increase was less prominent in countries that were less “welcoming”. In the context of this study, “welcoming” was defined as displaying positive attitudes towards immigrants but not necessarily providing them with resources. More specifically, the purpose of the Larkin et al.’s [14] study was to examine the impact that local populations’ deep-seated attitudes toward immigrants have on housing prices. The Larkin et al. [14] study, which incorporated “welcoming” characteristics, is of unique interest with respect to this study because Chicago is a self-proclaimed “Welcoming City” and has lived up this appellation by expending significant resources on migrants, which could also be assumed to lead to significant increases in pricing.

While not examined in depth as compared to the home sales market, the rental real estate market has shown results similar to those noted above for housing prices. For example, using metropolitan statistical area (MSA)-level data, Ottaviano and Peri [15] as well as Saiz [16] found a migrant inflow equivalent to 1% of a city’s population to be associated with 1% increases in average rents and housing values. Saiz [16] improved on earlier research by including additional variables such as economic cycles. Examining regional housing markets and basing their analysis on monthly indexes of median house prices and median house rents, Nguyen et al. [17] found that immigration had a greater impact on house rents than on house prices. Examining rental prices in Miami after the shock of the Mariel boatlift, Saiz [18] found that it had increased Miami’s rental population by 9% in 1980 and was associated with a higher increase in rents than it had with the influxes of groups in 1979 and 1981. Mussa et al. [19], who examined the effects of immigration on both house purchase prices and rentals, found that prices increased not only in the MSA that received the influx of immigrants but also neighboring MSAs.

Prior research has also examined the impact of rental assistance on the real estate rental market, though not at the depth of research presented here. Van Der Vlist et al. [20] examined the effect of a rent assistance program on the rental real estate market in Israel, which offered a fixed monthly allowance to households regardless of how recipients chose to live. They found that the government’s rent assistance program led immigrants to offer their combined rent allowance to the market by sharing a dwelling with another household, thereby causing rents to rise sharply. This sharp rise prevented non-immigrant households from accessing the rental market, leaving some homeless and creating social disorder. Given the breadth of benefits offered to them, we expect the 2022–2024 influx of migrants entering Chicago to have a positive and significant effect on rents. Furthermore, given the availability of data to the market, we also expect this response to occur relatively soon following the migrants’ arrival.

A common shortcoming of prior research on the real estate rental space is that the rental data employed in the analysis are not adequately specific. For example, the data used in the studies previously noted covered broad time periods, often months, and encompassed entire MSAs, which can be quite large and for which only aggregate data are provided. In contrast, the author employed data at multiple listing service (MLS) levels for this study. The Chicagoland MSA is the largest MSA in the Midwest, encompassing over 10,000 square miles and includes the city of Chicago and its suburbs spanning 14 counties across Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin. With an MSA encompassing such a broad area, the study concentrated on a single city within it, Chicago, where the author had access to apartment-level data that are updated daily rather than monthly or quarterly. Additionally, previous studies used aggregated data on immigrants gathered solely from the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which can fail to include the sizeable group of individuals that enter illegally. A dataset detailing illegal immigrants cannot be directly linked with MSA-level data except at the annual level, and doing so would distort results. Finally, the fact that the INS-aggregated dataset does not necessarily link the timing of a foreign person with the actual date of entry can cloud results [16]. In contrast, the data in this study, which focused on illegal immigrants transported to Chicago, were provided by the city on a daily and weekly basis, thus more accurately reflecting the movements of immigrants over small time increments.

3. Data and Methods

In this research, the author sought to examine the effect of immigrants on rental prices at a much more granular level, both temporally and geographically, than use of the public databases maintained by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and MSA-level data enables. In contrast, the data utilized were from the detailed practitioner database of the multiple listing service (MLS) and by the city of Chicago on a daily and weekly basis regarding migrant arrivals and shelter occupancy [4].

3.1. Geographical Area

The author chose the Chicago market for this examination because it is one of the largest metropolitan areas in the United States and its receipt of a large influx of migrants made it the recipient of a substantial amount of media attention. Chicago ranked only second after New York City in number of migrants received by a city [21]. Additionally, not only was the sheer number of migrants substantial over the period of interest, but Chicago’s government was also unique for the excessive generosity of benefits it afforded this group. In fact, according to Cities Index of the New American Economy, an immigration advocacy and reform organization, Chicago was voted the most welcoming city for immigrants in the country even before providing the 2022–2024 influx of immigrants subsidies [22].

3.2. Data Selection

Chicago provided an ideal case study because it operates under an independent MLS, allowing for a concentrated focus. For example, Illinois alone has dozens of MLS, each requiring separate membership. In fact, Chicagoland itself utilizes at least six MLS. The data from the MLS chosen to be examined belong to Chicago proper and are hand-collected for all available rentals in Chicago. The data collection process began on 31 August 2020, approximately two years prior to arrival of the first immigrant bus and ended on 1 September 2024. The total number of apartment data collected across the 77 Chicago MLS tracts was 121,396. Table 1 separates these listings by time, and this total includes both units that were rented and that were still actively listed for rent as of the date the data were collected. Of those 77 tracts, only 20 housed the city’s 27 migrant shelters, with most tracts containing only one migrant shelter with the exception of one tract containing four.

Table 1.

Disbursement of rental units (Panel A) extracted from the multiple listing service and (Panel B) with respect to time period.

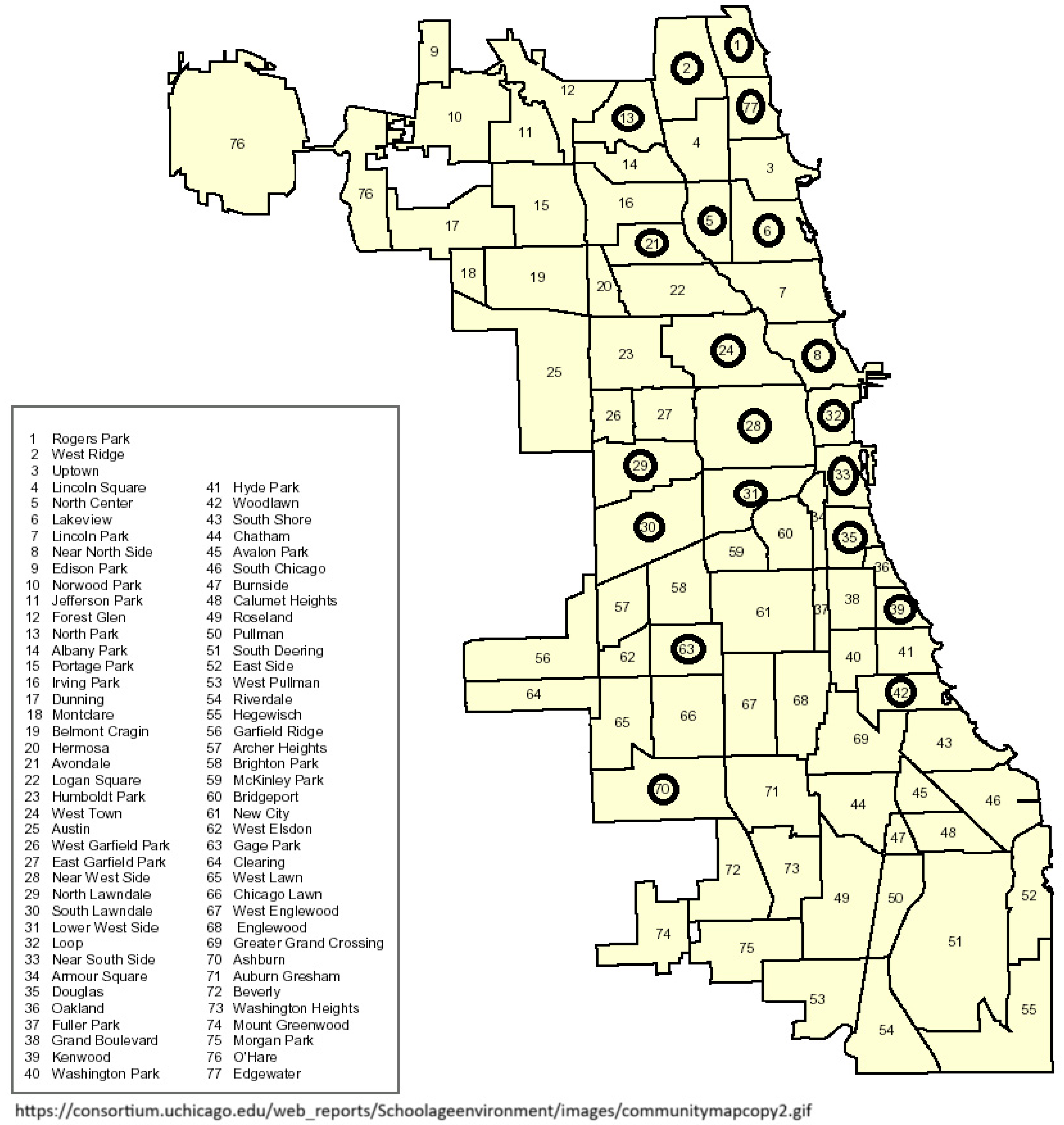

The map in Appendix B shows Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods and designates those that have housed, or are currently housing, migrant shelters. For this research, the 77 tracts were divided into three groups, and Panel A of Table 1 displays the distribution of rental listings by tract. The first grouping comprised those 20 tracts containing migrant shelters, and so, if the hypothesis that the presence of a migrant shelter in a neighborhood causes rental prices to rise is true, these areas would see the largest increase in rental prices. The second group comprised neighborhoods adjacent to the neighborhoods in the first grouping, which the author hypothesized would exhibit a slightly muted impact in response to the presence of the migrant shelter compared to the first group. Lastly, the third group consisted of neighborhoods not containing a shelter and not bordering a neighborhood with a shelter. The author hypothesized that these more distant areas would exhibit the lowest increase in rental rates because the migrants arrived with nothing more than what they could carry, and the shelters became the epicenter of not only their homes but also their ventures, such as selling water or food for income. Given their lack of resources and mobility, the author hypothesizes that migrants would be more comfortable in areas with which they were already familiar. Panel A of Table 1 shows the distribution of units based on shelter location, whereas Panel B shows the distribution of these units by date.

Panel A in Table 1 shows how the collected rental units were disbursed with respect to shelter locations. So, the number under “No Shelters” is of rental units located in tracts that had no shelters and were not adjacent to a tract containing a shelter; the number under “Shelters Adjacent” is of rental units located in tracts that did not contain one or more shelters but were situated adjacent to a tract that did contain a shelter; and the number under “Shelters Present” is of rental units located in a tract that contained a shelter. Panel B in Table 1 displays the distribution of rental units with respect to time period. The first column provides the number of rental units available before the migrant influx and is thus denoted “Pre-Migrant Mobilization”; this acted as the control period in the analysis. Second is the “No Subsidy” period, which began with the initial arrival of migrants and thus preceded the subsidies being offered. Third is the “Beginning Full Subsidy” period, during which subsidies offered to migrants peaked. The last column, titled “Beginning Reduced Subsidies”, covers the period when subsidies to immigrants were reduced.

3.3. Methodology

Model specification started with the inclusion of those variables that were theoretically expected to have the greatest impact on real estate rental prices. To confirm the validity of the selected variables, their correlations were calculated. Next, VIF and eigenvalues were calculated to check for the presence of multicollinearity. Only inflation showed minor multicollinearity, and so this variable was retained to act as a proxy for broad economic impact. Lastly, standard errors were checked for heteroscedasticity and no inconsistencies were identified. Having checked these, the researcher performed the log-linear multiple regression.

As shown in Appendix B, of the 20 tracts that contained one or more migrant shelters, 8 did not border another tract also containing a shelter. The limited mobility of migrants living in emergency shelters leads to the following question: Did the prices of rental properties within the same tract as a shelter increase more quickly than those in areas that were adjacent to it or those that were not adjacent? To examine this question, the author conducted a log-linear multiple regression analysis using several variables relating to the unit characteristics, the time period, and location in order to determine impact on rental prices.

Table 2 lists variables that could impact apartment pricing in the study’s log-linear regression analysis. This information was collected from the MLS. The location and time variables are dummy variables, i.e., they take only values of 0 or 1, whereas the others are integer or continuous. Of the roughly 50 data points that professional brokers provided for each MLS rental listing, only those shown in the table were relevant to the analysis. The variable “Built Before 1978” served as a proxy for the age of the apartment building, which would likely affect rental price and which the MLS does not provide. The 1978 cutoff was included because of the Residential Lead-Based Paint Hazard Reduction Act of 1992, which requires sellers and landlords to disclose known lead-based paint hazards in homes built prior to 1978 to protect occupants from exposure to lead [23]. Appendix A in the appendix provides descriptive statistics for these variables.

Table 2.

Variables included in the model. Data obtained from MLS.

The researcher fits the log-linear regression model both with all listings (i.e., active and rented) and without active listings because their list prices could not be assumed to adequately reflect market rents as determined by a ready, willing, and able renter. The following section presents and discusses the results obtained from fitting both regression models.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 3 displays the coefficients obtained from both regression models: Model 1 fitted to data for active rental and rented listings and Model 2 for only rented listings. Model 1’s independent variables include price per square foot, whereas listings that did not include square footage were omitted in fitting Model 2. Square footage data was the most frequently omitted by agents and was thus not available for 29,583 of the listings. Nonetheless, the coefficients of the two models did not differ substantially.

Table 3.

Log-linear multiple regression coefficients for Models 1 and 2.

Viewed broadly, the results shown in Table 3 support the researcher’s expectations. For example, Model 1’s results indicate that the impact of the migrant presence on rental prices was substantially significant for those periods during which subsidies were available. The results of the full and reduced subsidy periods were greater than for the period between the migrants’ but before they began receiving subsidies. More specifically, and with a base of $1000 selected for convenience, Model 1 predicted an increase of $9.69 (exp(0.00964) − 1)*1000) for the no subsidy period but an increase that was 4 to 6 times greater during the subsidy periods: $37.97 and $56 for the reduced and full subsidy periods, respectively. In other words, the availability of subsidy funds appeared to have a significant impact on the rental real estate market. Rental real estate prices for neighborhoods that housed a shelter or bordered a neighborhood that did so also increased at a significant rate in contrast to those areas that neither contained nor bordered an area containing a shelter. Specifically, continuing with an assumption of $1000 base, rental apartments located in a shelter neighborhood increased in price by $283.47, while in those adjacent neighborhoods increased in price by $291.20. Thus, proximity to a shelter appeared to have a significant and positive impact on the rental market. The other variables intended to act as controls produced predictable results. For example, Market Time and Built Before 1978 had negative and statistically significant effects on rent. Similarly, size as measured by Sq Ft, Bedrooms, and Inflation all positively affected rental prices, though inflation was only significant in the second model when the variables Sq Ft and Price Per Sq Ft were omitted.

Table 4 displays the results of the models based on the reduced sample where rentals considered active were omitted. While this reduced the sample by only 3370 listings, this was a worthwhile avenue for investigation since a listing provides only an “asking” rent and thus does not necessarily reflect the true market value of the rent. As in Table 3, Models 1 and 2 in Table 4 are based on the data containing square footage of the rental property and those not containing it, respectively. As can be seen, the results obtained for these datasets do not differ substantially from those shown in Table 3. For example, in Model 1, the impact on rental prices is highly significant for those periods during which the subsidy was given. Based on a rent of $1000, the results predict that apartment rents would increase by $38.21 and $56.54 during the full and reduced subsidy periods compared to the no subsidy period. Rental real estate prices also increased at a significant rate for those neighborhoods that housed a shelter or bordered a tract containing a shelter compared to those areas that did not. Given a base rent of $1000, the results show an increase of $299.66 for those areas that bordered a shelter neighborhood and $291.11 for those neighborhoods that housed a shelter. Thus, again, proximity to a shelter apparently had a significant and positive impact on the rental market. The coefficients’ signs were as expected, with only the variables Market Time and Built Before 1978 having a negative impact on the rental price. Additionally, Table 4’s Model 2, which omitted the square footage variables, yielded a similar outcome, with only inflation changing, being both larger and also more significant than in Model 1.

Table 4.

Linear-log multiple regression results using the reduced sample.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to extend the research in the rental real estate market by examining how rental rates respond to an influx of migrants. The unique contribution of this study focuses on how rental real estate pricing reflects the significant subsidies received by migrants when rental prices are examined on an apartment and neighborhood basis. The dataset utilized allowed for this granular study and provided a unique opportunity to examine migrant and subsidy impacts at the rental level rather than at the MSA or the city level, both of which have been examined frequently due to the public availability of these data.

As the study results showed, subsidies were associated with an increase in rental real estate pricing of up to 5.6%. Furthermore, neighborhoods that housed migrant shelters or were adjacent to neighborhoods that did so exhibited a significant increase of up to 29.97% in rental rates compared to those neighborhoods that did not house a shelter and were not adjacent to shelter neighborhoods. Practically, Chicago property owners of rental real estate located in certain neighborhoods were likely the recipients of increased earnings during the periods of increased migration and were even more so once subsidies were enacted. Professionally, this study exemplifies how well-informed real estate managers and owners can capitalize on policy changes at the city level to capture higher profits, which in this study climbed to a combined rate exceeding 35%. However, these increased profits were at the expense of taxpayers’ funds, the primary source of subsidies. Additionally, this would imply that non-migrants were likely competing for a fixed number of rental units and were likely forced to directly compete with subsidized migrants.

Future research could examine where displaced non-migrant residents moved to and the rental real estate market there. Given that the apartment supply is fixed over the short term, any apartments that absorbed the renters within a short 3- to 9-month period likely forced some non-migrant residents out of the market. A final avenue worth consideration is to examine court filings for non-payment. Subsidies were only permitted for 6 months, and this expiration of funds could shift the market once again. Hypothetically, upon the expiration of subsidies, the recipients would no longer be able to afford their apartments, resulting in eviction. While this may be the case, the likelihood that real estate rents would return to pre-subsidy levels at turnover would probably be minimal.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The primary data was accessed on 26 June 2024 from https://connectmls.mredllc.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three-letter acronym |

Appendix A

Select Descriptive Statistics on Properties with Price Changes. This table provides select descriptive statistics for properties included in this analysis.

| Label | N | Mean | Std Dev |

| Rental Price | 121354 | 2181.98 | 1345.2 |

| No Shelters and None Adjacent | 121354 | 0.0633683 | 0.2436253 |

| Shelters Present | 121354 | 0.6402261 | 0.479936 |

| Shelters Adjacent | 121354 | 0.2964056 | 0.4566739 |

| Pre-Migrant Mobilization Period (D) | 121354 | 0.6242975 | 0.4843058 |

| No Subsidy Period (D) | 121354 | 0.0415231 | 0.1994976 |

| Full Subsidy Period (D) | 121354 | 0.1888772 | 0.3914126 |

| Reduced Subsidy Period (D) | 121354 | 0.1453022 | 0.3524067 |

| Market Time | 121340 | 30.2858414 | 65.9846312 |

| Built Before 1978 (D) | 121354 | 0.6837187 | 0.465026 |

| Rooms | 121352 | 4.6195613 | 1.4360972 |

| Price Per Room | 121354 | 486.656899 | 238.4851 |

| Bedrooms | 121354 | 1.8103565 | 0.9845893 |

| Price per Bedroom | 121354 | 1267.7 | 613.221833 |

| Price Per Sq Ft | 29583 | 3.6703982 | 74.3181895 |

| Approximate Sq Ft | 121354 | 843.192627 | 691.253886 |

| Inflation | 121354 | 0.0040246 | 0.0052807 |

| Log Rental Price | 121354 | 7.5797425 | 0.435242 |

Appendix B

Chicago Neighborhood Map. This Chicago Neighborhood Map outlines the 77 unique neighborhoods with each bold circle representing a neighborhood that houses a migrant shelter.

References

- Rumore, K. Chicago’s More than 40-Year History as a Sanctuary City. Chicago Tribune, 6 February 2025. Available online: https://www.chicagotribune.com/2025/02/06/timeline-chicagos-more-than-40-year-history-as-a-sanctuary-city/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Cherone, H. What Does It Mean That Chicago is a Sanctuary City? Here’s What to Know. WTTW, 20 October 2023. Available online: https://news.wttw.com/2023/10/20/what-does-it-mean-chicago-sanctuary-city-here-s-what-know (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- CHI311. Immigration Frequently Asked Questions. 2024. Available online: https://311.chicago.gov/s/article/Immigration-frequently-asked-questions?language=en_US (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- City of Chicago. New Arrivals Situational Awareness Dashboard. 2024. Available online: https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/sites/texas-new-arrivals/home/Dashboard.html (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Lee, M. Illinois Will no Longer Allow Landlords to Consider Immigration Status. Fox News, 14 July 2023. Available online: https://www.foxnews.com/us/illinois-will-no-longer-allow-landlords-consider-immigration-status (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Kane, L.; Rodriguez Presa, L. Migrants Are Leaving Chicago Shelters with the Help of Rental Assistance. Some Landlords Are Skeptical, Others Step in to Help. Chicago Tribune, 21 July 2023. Available online: https://www.chicagotribune.com/2023/07/21/migrants-are-leaving-chicago-shelters-with-the-help-of-rental-assistance-some-landlords-are-skeptical-others-step-in-to-help/ (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Schorsch, K. Cook County Approves the Sending of Up to $70 Million to Chicago to Feed Migrants. Chicago Sun Times, 18 April 2024. Available online: https://chicago.suntimes.com/politics/2024/04/18/cook-county-migrant-funding-70-million-chicago (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Norman, G. Chicago Residents Rip Mayor over Spending on Migrants: ‘Worst Mayor in America’. Fox News, 3 December 2024. Available online: https://www.foxnews.com/us/chicago-residents-rip-mayor-over-spending-migrants-worst-mayor-america (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Crown, J. Chicago’s Migrant Crisis Raises Questions of Equity. Crain’s Chicago Business, 20 February 2024. Available online: https://www.chicagobusiness.com/equity/chicagos-migrant-crisis-divides-communities-over-equity (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Accetturo, A.; Manaresi, F.; Mocetti, S.; Olivieri, E. Don’t stand so close to me: The urban impact of immigration. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2014, 45, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopy-Ramdhany, N.; Seetanah, B. Does Immigration Affect Residential Real Estate Prices? Evidence From Australia. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2020, 15, 290–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, F. Housing price, mortgage interest rate and immigration. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2020, 28, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Z.; Blickle, K. Immigration and the Displacement of Incumbent Households. 2018. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3131519 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Larkin, M.P.; Askarov, Z.; Doucouliagos, H.; Dubelaar, C.; Klona, M.; Newton, J.; Stanley, T.D.; Vocino, A. Do house prices ride the wave of immigration? J. Hous. Econ. 2019, 46, 101630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano, G.; Peri, G. The Effected of Immigration on U.S. Wages and Rents: A General Equilibrium Approach; Centre for Economic Policy Research: London, UK, 2008; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1140078 (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Saiz, A. Immigration and housing rents in American cities. J. Urban Econ. 2007, 61, 345–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Balli, H.O.; Balli, F.; Syed, I.A. Immigration and regional housing markets: Prices, rents, price-to-rent ratios and disequilibrium. Reg. Stud. 2022, 56, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz, A. Room in the kitchen for the Melting Pot: Immigration and Rental Prices. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2003, 85, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, A.; Nwaogu, U.G.; Pozo, S. Immigration and housing: A spatial econometric analysis. J. Hous. Econ. 2017, 35, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vlist, A.J.; Czamanski, D.; Folmer, H. Immigration and urban housing market dynamics: The case of Haifa. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2010, 47, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishti, M.; Putzel-Kavanaugh, P. After Crisis of Unprecedented Migrant Arrivals, U.S. Cities Settle into New Normal. Migration Policy Institute, 1 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- New American Economy. Available online: https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/cities-index/profile/chicago/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- National Association of Realtors. Lead-Based Paint. Available online: https://www.nar.realtor/lead-based-paint (accessed on 15 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).