Abstract

Healthcare is a dynamic and ever-changing phenomenon and is subject to multiple challenges, particularly concerning sustainability and cost issues. The literature identifies bed space and problems related to the lack of hospital beds as being directly or indirectly related to both admission and discharge processes, with delays in in-patient discharges being identified as a variable of significance when it comes to a health system’s overall performance. In this respect, the aim of this research was to explore factors related to delayed discharges in an acute hospital setting in Malta, a small European member state, through the perspectives of health professionals. This study followed a qualitative approach. Semi-structured interviews (n = 8) and focus groups (n = 2) were conducted with a diverse group of experienced health professionals. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all data were treated with strict confidentiality throughout the study. The sample was limited to professionals working in adult, non-specialized healthcare settings. Manual thematic analysis was carried out. Codes were grouped to derive seven main themes, which were identified after carrying out the thematic analysis process on the transcripts of the interviews/focus groups. The derived themes are the following: (a) a faulty system, which is open to abuse and inefficiency, (b) procedural delays directly impacting delayed discharges, (c) long-term care/social cases as a major cause of delayed discharges, (d) the impact of external factors on delayed discharges, (e) stakeholder suggestions to management to counteract delayed discharges, (f) the impact of COVID-19 on delayed discharges, and (g) inter-professional relationships. Factors related to delayed discharges and the effects of delayed discharges on the hospital emerged from the main findings, together with specific potential interventions to minimise delays in discharge. Health professional interactions and the effects of inter-professional relationship setbacks on delayed discharges were explored, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital dynamics and additional delays were also addressed. This information is intended to provide hospital administrators with data-driven internal organisational evidence to guide them through changes and to inform future decisions regarding hospital performance and efficiency from a discharge delay perspective.

1. Background

Healthcare is a dynamic phenomenon, and the challenges facing healthcare are ever changing, with increased technological advances [1] and issues of sustainability [2] and waste reduction leading such changes [3]. In recent years, these challenges have become more pronounced in both developed and developing countries [4], mainly due to scarcity of resources and rising costs, a reality that has been more noticeable in the light of the recent COVID-19 pandemic [5]. One of the most crucial healthcare resources is bed space, which is intricately linked to admission and discharge processes [6]. Delayed discharges have emerged as salient in the health literature arena, in their impact on health systems’ efficiency and effectiveness in delivering optimal performance levels [7].

A scoping review [8] (p. 3) revealed hospital management [9,10,11], procedural delays [12], and faulty discharge planning [13,14] as the most salient antecedents. This scoping review also provided a comprehensive definition of a delayed discharge, namely “an instance where a medically fit patient is kept needlessly in hospital due to organisational/operational factors when a patient is flagged as in need of alternate level of care and is delayed because of deferred transition of care and/or lack of external transfer-of-care arrangements”. Other research investigations uncovered a tendency for delays in patient discharges to be due to inappropriate community service support [6], a lack of adequate social services [15], and a lack of nursing home beds and/or rehabilitation beds [16,17]. The degree of social isolation [3] and the patient’s age [18] were also identified as contributory factors to delayed discharges. A number of strategies employed by specific healthcare organisations to counteract the negative impact of delayed discharges were also uncovered [19,20,21].

The extensive literature base pointed towards the relevance of delayed discharges in improving healthcare efficiency and effectiveness, especially in a secondary/tertiary care setting. Addressing the issue of delayed discharges in small European member states may, in fact, prove to be particularly important because of their limited numbers of acute hospital facilities and bed space. In addition, spillover to other acute hospital settings is limited at best, and not possible at all in certain situations. Eurostat (2021), in fact, revealed a great discrepancy between acute bed numbers in small European states and larger ones (with Luxembourg and Liechtenstein having 319 and 89 acute care beds per 100,000 population, respectively, in contrast to Germany and Romania possessing 581 and 555 acute care beds per 100,000 population, respectively) [22]. This makes hospital beds an extremely limited resource in small member states, perhaps more so than in larger countries. The need to address delays in the hospital discharge process, thereby, becomes a more pressing and urgent need in smaller member states.

Using the case study approach, the aim of this research investigation was to explore factors related to delayed discharges in an acute hospital setting in Malta through the perspectives of health professionals. To the authors’ knowledge, this research investigation was the first of its kind in Malta and will add significant perspectives on delayed discharges from a context-specific point of view.

The Maltese healthcare system comprises both a public and a smaller private sector [23]. Malta has a very high population density when compared to the rest of Europe, with its population having grown significantly (>7%) over the past few years [23]. Due to the fact that the absolute majority of secondary and tertiary care in Malta is provided by publicly owned hospitals, the hospital under study is an acute general hospital that caters for the bulk of emergency care [23]. The Maltese health system has been directly affected by the ever-increasing challenges brought about by increased frailty due to population ageing, together with an overall exponential growth in immigration and a high seasonal incoming tourism industry [23]. This often results in frequent Accident and Emergency (A&E) overcrowding, as well as high rates of bed-blocking at ward level due to long-term care patients waiting for further care in other institutions or in the community. This turn of events is directly responsible for a bed occupancy of between 80 and 85% over the past decade, a rate which stands above the EU average [23]. Furthermore, comparative insights from other small EU member states such as Cyprus, Luxembourg, and Estonia further highlight the structural centralization characteristic of Malta’s health system. While all these nations face capacity limitations due to scale, Malta distinguishes itself through its pronounced dependency on a single acute public hospital for nearly all secondary and tertiary care. This centralization contributes to greater systemic vulnerability, particularly regarding discharge pathways, as there is limited flexibility for patient spillover or redistribution. In contrast, although small, countries like Luxembourg and Estonia have adopted more distributed or mixed-care models that incorporate regional facilities and private partnerships, providing additional buffers during peak discharge pressures. As a result, delayed discharges in Malta are not just the outcome of procedural inefficiencies but are deeply embedded in the structural design of its centralized health system.

Against this background, this study aims to explore the perspectives of healthcare professionals regarding systemic and procedural factors contributing to delayed discharges from a Maltese acute hospital. Specifically, the objectives were to (i) identify contributing factors to delayed discharges; (ii) understand health professionals’ perspectives; and (iii) propose context-specific recommendations.

2. Theoretical Framework

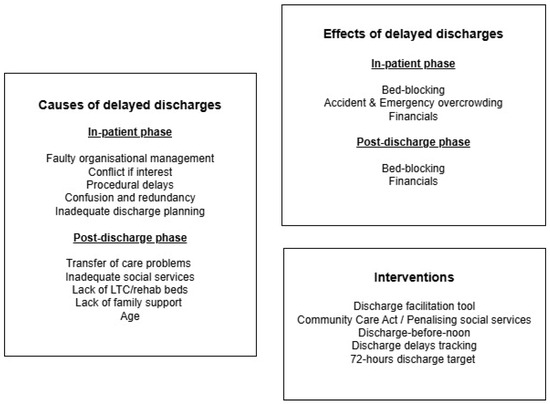

The study was based on a theoretical framework [8] following a scoping review on delayed discharges [8]. The model emerged with a cause-and-effect representation of delayed discharges, together with specific recommendations for avoiding this phenomenon.

This framework proposes that delayed discharges are mainly the result of faulty organisational planning [13,24], inadequate discharge planning [25], and transfer of care problems [7,15]. Delayed discharges, in turn, are partly responsible for bed-blocking [26] and A&E overcrowding [27], with the negative financial impact such occurrences bring with them [28,29]. The model also outlines specific actions to counteract the aforementioned effects of delayed discharges, such as utilizing a discharge delay tracking [20] list, a discharge facilitation tool [21], and others. This literature-based framework formed the basis of this research investigation. The next section provides a detailed description of the study methodology, outlining the methods used for data collection and analysis.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

This study was conducted in Malta’s primary acute care hospital between January 2022 and August 2022. This is the only government-run general hospital on the island and receives patients from across all medical fields. A qualitative descriptive design was adopted, using a constructivist lens to explore participants’ lived experiences and operational insights. In this respect, a case study approach was chosen for the purpose of this research investigation, with interviews being utilized as the data collection tool of choice. A case study approach was selected to gain in-depth, contextualized insights into health professionals’ experiences—an approach particularly suited for exploring complex, perception-based phenomena. This study followed Merriam’s qualitative tradition, which emphasizes the use of prior literature to develop a guiding theoretical framework. Unlike Yin’s mixed-method triangulation model or Stake’s emergent design, Merriam’s approach supports a more structured, literature-informed qualitative inquiry [30,31].

Target Population and Sampling Technique

An extensive collection of data is warranted in an effort to gather as much information as possible [32]. A rich description of the case should emerge, and this is bound to provide a holistic picture of the phenomenon under study, because the data gathered would have been acquired from participants, who are themselves involved in real-life situations [30]. For this reason, the sample was chosen from three main levels of the organisation under study:

- The strategic level (top management);

- The tactical level (middle management);

- The operational level (lower-level employees).

The sample was chosen using a theoretical sampling technique, as participants were chosen based on the theoretical framework acquired from the evidence-based model already described [8]. This strategy is also in line with Merriam’s case study approach [30]. This sampling technique was deemed to be ideal and appropriate to promote both insight and understanding of the research phenomenon under investigation. Table 1 (below) shows the stakeholders selected for this study based on the model developed from the scoping review [8].

Table 1.

Points derived from theoretical model as related to chosen sample.

The stakeholders were divided based on the different levels of hospital management, namely strategic, tactical, and operational (Table 1 above). The number of participants in each stakeholder group was proportionally distributed among the managerial levels. This was done so as to keep the sample as representative as possible in relation to the three strata (strategic, tactical, operational).

Both doctors and nurses were chosen from across the board, namely nurses from medical, surgical, and admission unit settings and doctors from different specialties and seniority levels. This was done in an attempt to get as representative a sample as possible, which would be prone to yield an all-round holistic view. Specialty units were excluded from the study because the modus operandi of such units is independent from the rest of the hospital, with each unit requiring a study of its own. Most of the participants chosen for this study had two to five years’ experience working in their own profession, so as to increase the probability of extracting valuable, experience-based information (except for junior doctors, who had less than two years’ experience but whose input was deemed important to represent the views of the lower-level members of the medical field). Nurses were reached through their ward managers, who distributed the invitations via email along with information letters, consent forms, and inclusion/exclusion criteria. Interested nurses contacted the researcher directly by email. Doctors were contacted via email using the intra-hospital medical specialty list to select participants from various specialties, ensuring diversity. Due to their smaller numbers, other health professionals were approached personally within their departments. The researcher did not personally know any of the nurse or doctor participants; however, it was more challenging to maintain anonymity with professionals from smaller groups, such as geriatricians and discharge facilitation team/discharge liaison nurse staff.

3.2. Data Collection

The lead researcher assumed the role of an inside learner, in that he was familiar with the dynamics of hospital processes. Although this fact contributed some potential for bias, it nonetheless allowed for a more thorough understanding of the results obtained, thereby preventing interpretation bias. To this end, the researchers made use of third parties, who do not make up part of the hospital workforce, to countercheck the result interpretation during various stages of the research investigation.

Two data collection techniques were employed: semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Interviews provided individual perspectives, while focus groups enabled an interactive exploration of shared challenges. This method is effective in qualitative studies as the ‘face-to-face’ interaction involved is more naturalistic and therefore more likely to yield consistent answers [33]. The interview questions were also based on the pre-described research model (see Figure 1) [8]. The chronological order of the questions allowed for a more flowing, ‘conversation-like’ approach, while their open-ended structure ensured that participants felt free to veer off the main questions at will. The interviews were kept to around 30 min long so as not to tire participants out, which would result in a decline in the quality of the data collected. For both interviews and focus groups, a quiet room was selected to minimise the chance of interruptions. During individual interviews, only the researcher was present. However, a second colleague assisted during the focus groups to help capture nonverbal cues that might have been missed in the audio recordings.

Figure 1.

Evidence-based theoretical framework for delayed discharges (adapted from scoping review [8] (p. 3)).

Pilot interviews were carried out before the start of the main study to root out inconsistencies and misconceptions in the questions posed [34]. Two such interviews were, in fact, utilized for this purpose. This was found to be very effective in clearing misconceptions and making the interview sessions flow better in a structured manner.

English was the language of choice as all the participants taking part in the study were deemed to be proficient in the language. This measure was found to be very effective in avoiding translation bias, leading to a smoother transcription process later on.

Consent/permission letters were provided to participants pre-interview, explaining the nature of the research. In turn, interviews were audiotaped, with consent being obtained from all participants. Audiotaping the interviews allowed the researcher to focus on what respondents were saying (without pausing to take notes), while also allowing for a more accurate transcription of participants’ answers (with significantly fewer errors of omission).

Two focus groups were also utilized as a data collection method in this research study. These were audiotaped as well. Focus groups are in-depth interviews where participants are selected because they are purposive (even though they are not always representative) [35]. Participants were selected on the basis of their having significant contributions to offer on the topic under investigation, and they felt at ease conversing with the interviewer and each other [36]. This concept is related to participants’ applicability, where subjects are selected because of their knowledge of the area of study, with the synergy of the group interaction also being of extreme importance [37].

Focus groups were conducted solely when investigating doctors’ views and bed management personnel’s views. The doctor’s focus group consisted of 5 participants, while the bed management’s focus group was made up of 4 participants. The fact that these individuals were allowed to share views and opinions yielded valuable insights that would have been otherwise missed. Group homogeneity in the focus group sample is also beneficial as it increases the chances of participants feeling comfortable in sharing thoughts and ideas, thereby creating an environment of trust [38]. The homogeneity of the focus groups was reinforced by including only participants from the same profession who currently or previously worked together. This approach fostered greater cohesiveness during the sessions and encouraged participants to express themselves more openly. In turn, although focus group participant numbers may vary, smaller groups show greater potential as they stand less chance of becoming fragmented and disorderly [39].

3.3. Data Analysis

Interview audiotapes were manually transcribed by the researchers. The fact that all interviews were conducted in the English language eliminated the need for translation, thereby preventing translation bias. The doctor’s focus group was also transcribed in the same way. The bed management unit focus group data (which was not audiotaped but rather consisted of many pieces of scribbled notes made by the researcher and his associate) was organised in the form of questions and answers. This was done by close collaboration between the researcher and his associate in an effort to comprehensively capture all the information gathered as precisely as possible.

Thematic analysis was the method chosen by the researchers to analyse this qualitative data set. This entails searching across the transcribed data set to identify, analyse, and report repeated patterns [40]. The researcher who conducted the interview and focus group sessions carried out this process, occasionally referring to the colleague involved in the focus groups to confirm specific details or fill in any missing information in the transcripts. All researchers involved in the data analysis have a background in health systems leadership and training (as well as experience) in qualitative research. None of the research team were line managers of the participants.

Thematic analysis is not bound to any particular single research paradigm; it is very flexible and can be used within a wide range of frameworks involving study questions, designs, and sample sizes [40]. This method of data analysis goes well with a constructivist approach because it allows for the analysis of a wide range of data, highlighting the development of particular social constructs and allowing a set of commonly shared meanings to emerge [41]. The thematic analysis method adapted by Braun and Clerk (2006) was used, as this method is very widely utilized in qualitative research, thereby allowing for easier comparison with other research investigations. It was also deemed highly pertinent for this research investigation [40].

The method employed by Braun and Clerk (2006) [40] involves a number of steps, and these steps were used as a template for the data analysis of the interviews/focus group transcripts:

- Familiarization with the data: The interview/focus group transcripts were read multiple times by the researchers, with the prior process of manually transcribing data also helping to increase familiarization. This step was also found to be helpful in later stages of data analysis because it facilitated the derivation of inductive aspects from the collected data.

- Code generation: At this point, the researcher started looking for possible codes. A code is a piece of raw data [42], in this case, the transcripts, that can be assessed meaningfully as regards a particular phenomenon [42]. Codes must be very well defined and, as much as possible, should not overlap with each other [43]. The researcher decided to differentiate the codes identified into those that were inductive or deductive in origin, with inductive codes denoting ones guided by specific theoretical frameworks (most typically the interview questions, based on the scoping review findings) [44] and deductive codes, which consist of issues originating purely from the raw transcript data. Data extracts were labelled with pertinent codes, with some data extracts being labelled with more than a single code at times. Code identification was performed manually without the use of software. This approach was chosen to ensure the reliability of results through the application of human judgment. Although this method can be criticized for potential researcher bias, the coding of interview and focus group transcripts was conducted independently by two researchers. This helped to reduce bias. The two sets of codes were then compared and contrasted, resulting in a common set of codes. This process was particularly valuable in distinguishing between emergent and intentional codes, where some discrepancies between the researchers’ findings were expected. Codes that were not common to both researchers were either re-evaluated or excluded. The emergence of seven themes from the 41 derived codes occurred through collaborative discussions among all researchers, following a careful definition of each code (see Appendix A). It is important to note that determining data saturation was challenging due to the heterogeneity of the sample, which included a wide variety of health professionals. However, the researchers considered the high frequency of recurring issues across different respondents as a strong indication that data saturation had been reached.

- Searching/defining and naming themes: The researchers set out to identify themes from a deductive (specifically from the coded data) as well as from an inductive (based on pre-defined theories and theoretical frameworks) perspective. Codes were carefully grouped according to emerging headings in an effort to find commonalities, and these commonalities formed themes. This process was kept up until all available codes were placed under a specific theme. This information was organised in tabular form so as to facilitate analysis and presentation.Qualitative research is sometimes criticized for lacking scientific rigor and for being highly subject to researcher bias [45]. Validity denotes the accuracy with which findings reflect collected data, while reliability refers to the consistency of the research methods utilized [9]. Table 2 (below) explains how validity and reliability issues were addressed in this research investigation.

Table 2. Validity/reliability measures for rigor.

Table 2. Validity/reliability measures for rigor.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim by the interviewer. Data from different focus groups were analysed separately to preserve contextual integrity. Saturation was reached when no new themes emerged from subsequent data. This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the COREQ guidelines for qualitative research [46].

3.4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from both the hospital administration (Chief Executive Office, Director of Nursing, and Data Protection Officer) as well as from the University of Malta board of ethics (Form ID: 7248_19121983_). Participation was always kept voluntary, with all subjects giving their informed consent. In turn, the right to anonymity and privacy was safeguarded at every stage of the data collection process. Only the researchers handled the collected data, and this data was secured under password control and erased after the study ended. A second colleague assisted the researcher during the focus groups, serving as a passive observer to notice behavioural cues and help verify findings that might have been missed in the audio recordings.

4. Findings

Findings emerged using thematic analysis, with some factors being derived from pre-determined agendas the researchers put forward, while others actually surfaced from the respondents’ views and experiences.

The findings derived from this research investigation differed in some aspects from the general literature, although a number of similarities were also identified. In this section, the findings of the study will be presented in detail. Participant demographics are listed in Table 3 (below). This process was carried out on all the transcript data available, with the researcher creating a table to represent and define codes and assigning codes to study participants, while also outlining which participants referred to such codes (see Appendix A).

Table 3.

Participant demographics.

Table 4 represents the derived themes, quotes from all three levels of management, and the codes that allowed the themes to be identified.

Table 4.

Derived themes based on codes.

5. Discussion

In this section, the above-described themes will be addressed one by one, discussed, and compared to the general literature.

Faulty system which is open to abuse and inefficiency

Research participants identified the existence of a faulty hospital system dynamic as being primarily responsible for delays in discharge, particularly in relation to the system’s vulnerability to abuse and the resultant inefficiency. The literature revealed that faulty discharge planning stood at the core of faulty hospital systems abroad [47,48,49,50]. Other studies also identified a lack of proper co-ordination [49], service fragmentation, and a lack of co-ordinated service provision [51] as directly contributing to inefficiency.

The results obtained from this research investigation in relation to this theme vary greatly from the general literature. This theme was, in fact, embraced by most respondents across the board. Although discharge planning was identified as a hindrance, it was far from the only factor participants were concerned about. System abuse by patients, relatives, and health professionals themselves seemed to be a major issue brought forward by interviewees, particularly in relation to long-term cases. A lack of proper admission and managerial protocols was also mentioned by several respondents, while insufficient discharge planning inevitably surfaced as a contributor to a faulty system that results in delayed discharges.

“Rarely is there a discharge plan. Although they say that discharge planning should start from admission, I believe that in our hospital there is no appropriate plan”(Nurse 1).

There can be various reasons for such a discrepancy. System abuse by patients and relatives in relation to getting patients flagged for long-term care, particularly by resorting to third parties to bypass the system, can be partially attributed to the fact that Malta is a densely populated small nation where the population is closely knit, and where politics is very closely intertwined with everyday life. This drawback can be closely linked to respondents’ issues related to management not adhering to protocols, especially when it comes to A&E gatekeeping and admission criteria. According to the participants, these issues also seemed to stem from system abuse by patients and their families, with health professionals finding it difficult to adequately carry out their duties without proper managerial backup and protocols.

Nurses and lower-level doctors voiced the most concern about faulty discharge plans, but system abuse was apparent across the board, with almost all respondents referring to this phenomenon in some form or another. This was also particularly evident from the input of discharge facilitation team (DFT) members and charge nurses and their subordinates, as these health professionals were most prone to come across such instances during the course of their workday.

Procedural delays directly impacting delayed discharges

Procedural delays emerged as the basis for the second theme, supported by respondents through various identified codes. This finding is very much in line with the general literature, where a number of studies also came up with procedural delays as a major hindrance to an efficient patient hospital stay. These delays varied in nature across the literature, ranging from delayed diagnostic services [52] to medical imaging procedures that took too long to complete. Excess bureaucracy and redundancy were also identified as directly or indirectly contributing to delays in relation to specific procedures [13]. Some research investigations also identified conflicts of interest on the part of health professionals as being responsible for discharge delays [24,53].

Respondents in our study identified procedural delays as being the second most common cause of delayed discharge. This ranged from high bureaucratic demands and excess clerical work to medical imaging and theatre delays (especially for orthopaedic surgery). It also became apparent to the researcher that while daily paperwork seemed to be on the increase for nurses, it was decreasing for the medical profession. From an operational standpoint, respondents also listed cleaning and transport arrangement delays, together with delays related to waiting for discharge letters (as quick discharge letters were not often utilized). Bed management unit respondents identified delays involving logistics in relation to patient transfers between wards or from the emergency department to wards as also being of particular concern.

These findings are in contrast to the general literature because the latter concentrated mainly on procedural delays related to medical imaging and other diagnostic processes. In our study, while respondents also identified the above as contributing to overall procedural delays, they also shed light on other problems, namely theatre procedures (which were delayed due to a lack of available theatres or theatre staff) and general hospital logistics related to patient movements between departments. This finding was widely acknowledged by the respondents, most particularly charge nurses and members of the bed management unit (i.e., from a tactical managerial perspective). The cheating issue also emerged as an issue of concern (especially for higher management), with the bed management unit identifying the practice of having ward departments deliberately delay the discharge process or outright mislead their superiors as regards bed statuses to avoid admitting new cases. Such a finding is altogether absent from the literature. Departmental managers also identified the cheating issue as a phenomenon that occurred relatively frequently and about which there is very little control.

Long-term care/social cases as a major cause of delayed discharges in MDH

Discharge delays being at the mercy of the number of long-term care cases is a well-established fact in the literature. Some authors point towards long-term care cases reducing the availability of hospital beds in acute care settings [54]. This finding was echoed by other authors who identified a bed-blocking problem and resultant A&E overcrowding as a result of having patients waiting for long-term care [26,27]. The need to increase the number of long-term care beds in an effort to decrease delays in discharge was pointed out as a needed strategy to avoid an added burden [49], while also highlighting the importance of more co-ordination between healthcare facilities in an effort to make the transfer of care process smoother [49].

The long-term care/social case problem emerged as a common concern for the interviewed stakeholders in this research investigation. The problem was twofold: a complex flagging process of getting patients flagged for long-term care as well as the actual time it takes for flagged long-term care patients to be physically transferred to a long-term care facility.

“For example, when we know a patient is unable to go home, we need to flag him for LTC. Doctor has to do referrals for geriatric and social worker and this involves paperwork and telephones. It then takes days/weeks for those people to come over and they then refer to the OT. To get a patient flagged for LTC, then you also have to inform the DFT after all this. It takes weeks”(Nurse 2).

Although respondents also voiced concern for rehab patients, this category was generally not considered to be as significant of an issue. The multi-layered process of having a patient flagged for long-term care was identified as being riddled with problems that translate to delays, namely the number and sequence of health professionals involved and the bureaucratic nature of the process. The complicated sequence in which certain health professionals (i.e., geriatricians, social workers, occupational therapists, and DFTs) are expected to review the patients and the time it took for these health professionals to actually do their reviews often needlessly extended the patient’s length of stay and led to nosocomial infections due to prolonged hospital stays caused by bureaucratic delays. In turn, sometimes patients did not meet the requirements to be flagged for long-term care (such as being a constant watch case).

Such views were particularly prevalent among nurses, doctors, DFTs, and charge nurses, who seemed to struggle to get through the flagging process on a daily basis. Members of the bed management unit (BMU) and the director (tactical–strategic levels) were, in turn, mostly concerned about the actual time it took for the flagged patient to be moved to an LTC facility. The discrepancy between views seems to highlight the fact that stakeholders mainly concern themselves with issues directly related to their job description and may be blind to other issues which do not directly fall under their professional jurisdiction.

A patient’s age was, in turn, identified by several respondents as being directly related to discharge delays due to increased patient needs related to increased dependency levels and lack of social support. These findings seem to point towards a long-term care flagging system that unnecessarily delays the flagging process, and thereby adds to the overall delay involved in having a patient transferred from a hospital to a long-term care facility. Such issues were also identified by the bed management unit as being especially responsible for the bed-blocking calamity and the resultant emergency department overcrowding situation. This finding is in contrast to the general literature, where the primary cause of delays is related to long-term care issues revolving solely around the actual waiting process to be admitted to a nursing home facility.

The impact of external factors on delayed discharges

This theme points towards the impact of factors outside the study setting on delays in patient discharge. The general literature revealed a number of external factors that negatively affect the discharge process. A number of authors shed light on a combination of inadequate nursing home/rehab spaces in terms of the bed shortage [7,17,55]. Another common factor authors in the literature uncovered revolves around social isolation and lack of family support/caregiver support in the community [6,55,56].

Respondents in our research investigation placed significant importance on the impact of external factors (i.e., factors originating outside the hospital) on delays in patient discharge. These issues were multi-faceted and varied according to the health professional’s perspective of the patients’ journey through the hospital system. Doctors and nurses seemed to be particularly concerned with lack of rehab/nursing home beds, which impeded long-term care cases from being transferred to another facility, thereby blocking whole ward areas for weeks/months on end.

“There are no empty beds in those places (LTC/rehab facilities) and many times patients have to wait for weeks or months to get there. This is an acute hospital and we are getting a lot of patients with LTC occupying beds here…lots of them”(Medical Officer 1).

Social workers and DFTs/DLNs’ concern seemed, in turn, to revolve around the lack of resources (both human resources as well as physical equipment) in nursing homes and in the community at large (i.e., people’s homes). This lack of resources, which ranged from caregiver support in people’s homes and nursing staff/physician support in nursing homes to hospital-related equipment in both long-term care facilities as well as the general community (such as motorized beds, nasogastric tube infusion pumps, amongst others), often resulted in patients getting stuck in hospital for extended periods of time.

DFT and DLN staff as well as charge nurses also cited the lack of proper family support as a major contributor to delayed discharges, which external factor resulted from a genuine inability to construct one’s social/professional lifestyle around the needs of an elderly loved one or from a lack of general interest based on a desire to abuse a hospital system which makes it fairly easy to do so. Participants across the board, in turn, seemed satisfied with the quality of community-based care (usually provided by the CommCare services) offered and provided to discharged patients in their own homes. They often cited that sometimes shortcomings in this department stemmed more from patients or relatives refusing the service or expecting too much out of it than the actual services not meeting the needs of their customers. From a strategic standpoint, the director, however, sustained that although community services themselves were satisfactory, for them to be effective, they had to be complemented with an actual human presence, as patients (particularly the elderly) needed to know that there was a person who they could easily reach at any moment. If people felt safe in the community, they were more prone to want to stay out of the hospital. DFT respondents also stressed the importance of an early discharge plan because some community services cannot be organised overnight and take some time (typically days) to kick in (such as the meals on wheels service). This often resulted in a patient’s discharge being unnecessarily delayed until the service was actually available.

“Even from the admission process itself…there is no real plan for a quick and efficient journey through the hospital system. It’s just get the patient admitted and then the firm will decide later on…even as regards whether the patient merits admission or not. A good chunk of patients should never be admitted“(Charge Nurse 1).

The respondents’ relative general satisfaction with the local community services provided varies from the general literature, a finding which may be attributed to Malta’s small geographical size, which tends to make community services easier to organise, so they will be relatively easily accessible to all. Malta’s situation seems, in turn, to be in line with findings abroad, where the demand for long-term care beds far exceeded the supply, which issue was particularly pronounced in the light of an increased lack of family support, social isolation, and ageing populations in the EU.

There was found to be no evident link between gender and respondents’ answers. Participants’ age and professional experience were, in turn, directly proportional, in that the older the participant, the more professional experience he/she had acquired. The younger medical professionals were more prone to find difficulty in logistical shortcomings, mainly because they completed the everyday ‘mundane’ tasks. The higher managerial strata were more concerned about the big picture. This also showed that health professionals across the board were very much mainly focused on their job description, and there was not much evidence for attempts to cultivate empathy by trying to understand how a problem or setback affects other professions. This is prone to shed a negative light on the concept of teamwork, which concept cannot be achieved if each profession is focused on ‘surviving’ in a work environment plagued by work overload and human resource limitations.

Interventions to counteract delayed discharges

One theme was identified to fall under this section, namely, stakeholder suggestions to management to counteract delayed discharges. This theme can be directly linked to the general literature in terms of the literature being rich in strategies employed by various acute health settings to decrease delays in patient discharge. This theme, in turn, outlined the suggested strategies stakeholders put forward to achieve this aim in their work settings. These strategies will now be compared and contrasted, with particular attention being given to the differences in the perceptions of stakeholders in this research investigation as opposed to the other settings in other countries.

A thing which immediately became evident was that, unlike other situations in the literature, where initiatives mainly consisted of small ward-based changes, respondents in this study setting concentrated more on system changes and changes in logistical dynamics throughout the whole hospital. Once again, suggestions varied according to the work-view of the specific respondent and the subjective perspective of the health profession in question.

Respondents placed particular stress on moving care from an acute health setting to people’s homes and the community in general for long-term cases, with the human resources (mainly care worker staff) who are currently used in the hospital being relocated to inside people’s homes. Although creating more rehab/nursing home beds was mentioned as a partial solution by some respondents, this measure was only considered as a short-term measure and by no means was it perceived as better than moving patients in the community to their own homes. Particular importance was also placed on the need for clearer protocols and guidelines for admission at the emergency department, a tool doctors can adhere to while feeling safer to do their job.

The intention here was to monitor which patients were admitted so as to prevent abuse and the creation of social cases, with doctors feeling free not to admit patients if they do not meet the necessary criteria. The director, the bed management unit, and the doctors themselves were particularly adamant about the importance of this issue.

The discharge delay problem on the day of discharge was also addressed, with solutions proposed by respondents, ranging from the use of quick discharge letters to creating a rotating roster basis for a number of doctors whose daily job would solely consist of writing discharge letters all day, thereby allowing firm medical officers more time to carry out their daily tasks. This would also provide discharged patients the opportunity to leave the hospital in a timelier fashion, thereby vacating beds earlier in the day.

From a logistical standpoint, response seemed to vary, and included suggestions such as faster online consultations (rather than paper-based manual ones), better and more timely discharge planning methods (formal or informal), having cleaners in wards for longer hours for more efficient discharge bed-cleaning, and less use of diapers in order to decrease patient dependency and avoid the discharge delays associated with increased patient dependency levels. Such initiatives proposed by stakeholders provide thought-provoking findings. These initiatives are relatively cheap to implement, and although they may result in some degree of resistance from both inside and outside the hospital setting, such measures would be prone to yield the desired positive results.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delayed discharges

One identified theme addressed issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on discharge delays: the impact of COVID-19 on delayed discharges and hospital dynamics. This theme emerged as a direct result of the COVID-19 phenomenon.

The COVID-19 pandemic was, by and large, considered by all respondents to have been detrimental and disruptive to overall hospital dynamics, in that all stakeholders agreed that the impact was felt in practically all areas. This also included the negative impact of delays in in-patient discharge, a finding that resonated the strongest when it came to operational and tactical stakeholders. Problems seemed to mainly revolve around the need for a negative swab test for any patient-related activity. This resulted in severe procedural delays, theatre delays, and transfer delays between hospital departments as well as other external entities (such as long-term/rehab facilities, which facilities were altogether closed off at times and were not receiving patients at all).

This extended the length of stay of practically every patient in the hospital and resulted in severe cases of bed-blocking, particularly when considering those patients kept in quarantine for days on end. The BMU and charge nurses were particularly impacted by the COVID-19 phenomenon as these health professionals had to face difficult hospital bed logistical situations, while the departmental manager respondents had extensive problems with staffing extra ward areas in the light of severe staff shortages made worse by staff being in quarantine.

Although the arrival of the vaccine alleviated some of this burden, stakeholders across the board still felt that the measures kept in place still hindered the patients’ stays and their daily work life. This included the ‘on and off’ swab testing and the constant transfer of COVID-positive patients across ward departments, with the resultant wasted bed space that such a divided hospital environment entailed. Some health professionals also stressed the increase in nosocomial infections when keeping patients for extended periods in the hospital due to delays punctuated by COVID-19 measures. There seemed to be a general consensus among respondents that it was high time that COVID-19 restrictions be lifted, and the hospital return to its normal modus operandi.

Inter-professional relations

The relationships between health professionals in relation to delays also emerged in the form of a theme, namely, inter-stakeholder interactions. This theme outlined respondents’ perspectives on interactions between them and other health professionals and how these interactions had the potential to induce delays in discharge. Role confusion was found to be a very common occurrence both in our study and in the literature, with the job descriptions of certain health professionals being unclear to others. In our research investigation, this was especially true regarding the medical profession confusing the roles of the DFTs, DLNs, and the social workers, and thereby asking for reviews from the wrong health professionals.

Another exceptionally evident finding was based on a combination of political problems between stakeholders responsible for the long-term care process (i.e., geriatricians, social workers, occupational therapists, and the patients’ families), where a lack of overall collaboration was reported by multiple respondents. This is somewhat in line with the literature, where authors identified some degree of role confusion [13] and poor inter-professional communication [51].

“So, we need to inform health professionals who to refer to and when not to refer to everybody. DFT, geriatrician, OT, social worker…this is what I think mainly leads to unnecessary delays. You have a lot of unneeded referrals and role confusion on the part of doctors”

The fact that only medical professionals are allowed to order laboratory tests online (or otherwise) was also found by both nurses and doctors to be greatly contributing to delays in the patient’s hospital stay. Such an issue can be relatively easily mitigated by hospital management at no monetary cost, although the better co-ordination of health professional interactions with regard to the long-term care problem might also involve a longer, more comprehensive effort. At a tactical level, the bed management unit confirmed that a lack of proper communication exists between ward departments and between the A&E department and the bed management unit itself. This chain of misinformation often involves mistakes related to misdiagnosis and wrong patient information, ultimately resulting in having to reallocate patients or, in some cases, prolonging the discharge process needlessly. Such communication breakdowns can also be addressed at a relatively low cost by hospital management.

6. Limitations

The researchers found there was a general lack of knowledge of the phenomenon under study (i.e., delayed discharges) on the part of some health professionals taking part in the study. Respondents’ answers were also found to be biased according to the particular health professionals being interviewed. There was, in fact, a tendency for participants to express opinions purely from the point of view of their own personal experiences (and that of their profession) on the work setting. There was also found to be some degree of reluctance on the part of certain health professionals as regards the discussion of certain issues. This is because, at times, issues became too personal, particularly when they concerned factors related to day-to-day job experiences. A case study approach may also be subject to the researcher’s personal bias, and the generalisability of the results is very limited. There may also be some degree of difficulty in clearly relaying the findings of the study because, unlike quantitative method findings, these cannot be provided in a clear-cut statistical manner. The case study approach, being qualitative in nature, also prevents result generalisability.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

The study aimed to explore the impact of delayed discharges on an acute hospital setting in a small European member state (Malta) through the perspectives of health professionals. Specifically, the objectives were to (i) identify contributing factors to delayed discharges; (ii) understand health professionals’ perspectives; and (iii) propose context-specific recommendations. Findings emerged, with a number of themes related to the cause and effect of delayed discharges, together with suggestions put forward by health professional stakeholders to decrease the occurrence of this phenomenon, both on a micro-setting level and on a national level. At the operational level, clearer job descriptions for health professionals are needed to streamline the consultation process and reduce inefficiencies. Implementing more robust, IT-enabled consultation systems could further support timely decision-making. At the tactical and strategic levels, the findings point to a need for expanded long-term care capacity, improved A&E admission protocols, and more structured discharge planning guidelines. Transitioning elements of care from acute hospitals to community settings—alongside appropriate staff reallocation—may help alleviate discharge delays and mitigate bed-blocking. Overall, these insights suggest a shift from a system-centred model to a more patient-centred approach as a sustainable direction forward. Furthermore, results suggest a need for structured discharge planning, improved interdisciplinary communication, and increased community care resources. These measures are essential to reduce discharge delays in Malta’s centralized acute care setting.

Findings also uncovered the relevance of inter-professional relationships and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delays in patient discharge to general hospital dynamics. While some of these outcomes were found to be in line with the general literature (being inductive in nature), others were deductive in nature and purely resulted from the efforts employed in this research investigation. Although this study was conducted in the framework of a small European member state health system, findings may also be applied to larger contexts.

Various recommendations can be put forward based on the study findings. Long-term solutions ranged from a need for urgent admission and discharge protocols and guidelines to a faster long-term care flagging process, coupled with more nursing home bed availability, together with the need for an increased human presence in community care and services rendered post-discharge. Furthermore, there is a need for clearer job descriptions and more robust IT systems to facilitate faster and more efficient consultation processes among health professionals. However, the researchers also managed to come up with a number of practical short-term low-cost recommendations that can be easily implemented with relatively minimal effort: (a) a discharge letter rotation system where house officers are assigned to discharge letter duty on a daily basis, (b) more access for nursing staff (and other health professionals) to authorise certain tests and procedures so as to take some load off medical officer duties, (c) more oversight on the part of hospital management to prevent cheating by wards in terms of false bed-state scenarios, and (d) providing a clearer guideline regarding the proper job descriptions of certain health professionals so as to prevent communication problems and untimely consultation processes. Although similar recommendations are noted in the broader literature and may be applicable to various healthcare settings, the measures proposed in this study were developed based on findings specific to the institution under investigation and the perspectives of its health professionals. As such, it would be inappropriate to generalise these results to other settings, given their strong context-specific nature.

This study draws particular attention to the long-term care problem that was very much present in the study outcomes, especially in the medicine wards. The flagging process was marked as a cause of delay affecting the actual waiting time for a long-term care bed. The implication for practice is in line with another implication revolving around the need for community-based care and the investment of additional human resources in this area. The study also signalled the need for admission protocols at the A&E department, together with earlier and more effective discharge planning procedures.

More research is also recommended in this area, particularly from a quantitative perspective, in order to create a framework that can be utilized for the development of an extension of the current patient dashboard system, and which can be used for tracking delayed discharges through the system (perhaps even predicting such delays before they actually occur). This will form the basis for a significantly more efficient patient-pathway dynamic. Such a quantitative approach would also pave the way for result generalisation and would help to move health systems to tackle problems from a system thinking viewpoint rather than a crises approach.

For further research, the findings of this study may also be contextualized within the broader European landscape, particularly when compared to other small EU member states such as Cyprus, Luxembourg, and Estonia. Comparative insights underscore the need to explore system-level reforms that enhance discharge agility—either through decentralization of services or stronger integration with community-based care pathways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.C.B., A.M., G.T. and L.G.; methodology S.C.B., L.G. and A.M.; software, A.M. and G.T.; validation G.T. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M. and S.C.B.; investigation, A.M.; resources, S.C.B. and G.T.; data curation, A.M., L.G., S.C.B. and G.T.; writing-original draft preparation A.M. and G.T.; project administration S.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Decleration of Helsinki, and approved by the Board of Ethics of the University of Malta (Form ID: 7248_19121983_) on 16 March 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was also obtained from participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy and ethical restrictions the research data cannot be made available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Code names, code definitions, and participants make use of them.

Table A1.

Code names, code definitions, and participants make use of them.

| Code ID | Code Name | Code Definition | Participant IDs Using Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Delayed discharges as part of daily work life | The prevalence of delays in discharge in the workplace in everyday life | MO1, NURSE3, NURSE5, CN1, NURSE7, DLN, DNM1 |

| B | Procedural delays as part of daily work life | The prevalence of delays as related to specific hospital procedures in everyday work life | MO1, BST1, NURSE1, NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE5, CN1, CN2, NURSE6, NURSE7, MO3, BST3, HST2, GER1, SW2, DNM2 |

| C | Complicated patients’ stay | Situations that give rise to complications in the patient’s stay which, in turn, extend the patient’s stay | HST1, BST2, NURSE4 |

| D | Most common form of procedural delay | Most common form of procedural delay in MDH identified by stakeholders | HST1, MO2, NURSE3 |

| E | Patients kept in hospital for convenience | Situations where the patients’ length of stay is extended for the professional convenience of health professionals or the patient | HST1, BST2, MO2, NURSE1, NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE4, NURSE5, CN2, NURSE7, MO3, HST2, GER1, DNM2, Director1 |

| F | Work redundancy as part of daily work life | Repetitive tasks done by health professionals on a daily basis that extend the patient’s length of stay | MO1, MO2, HST1, NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE4, CN1, NURSE6, NURSE7, MO3, BST3, HST2, DFT2, Director1 |

| G | The LTC flagging delay problem | Unnecessary delays related to getting a patient flagged for LTC | BST2, HST1, BST1, MO2, NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE4, DFT1, NURSE5, CN2, NURSE6, SW1, MO3, DFT2, GER1, HST2, DNM1, DNM2, BMU, Director1 |

| H | Discharge planning as a source of delay | Problems related to discharge planning (or lack thereof) and how this is linked with delays in patient discharge | HST1, BST2, MO1, NURSE1, NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE4, DFT1, NURSE5, CN1, CN2, NURSE6, SW1, MO3, BST3, HST2, DFT2, GER1, DNM1, DNM2, Director1 |

| I | Down-staffing of DLN team | Issues related to or originating from down-staffing of the DLN team | HST1, BST1, MO2 |

| J | Availability of community services and the impact on delays | Views of health professionals on community services provided and the impact of delays in patient discharge | BST2, NURSE1, NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE4, DFT1, NURSE5, CN2, NURSE6, NURSE7, SW1, MO3, BST3, HST2, GER1, SW2, GER2, DLN, DNM1, DNM2, BMU, Director1 |

| K | The impact of COVID-19 on discharge delays | The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital dynamics and delays in patient discharge | HST1, BST1, NURSE1, NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE5, CN2, NURSE6, MO3, BST3, DLN, BMU |

| L | The role of family support in discharge delays | The role of the patient’s family in relation to the discharge process | SW2, BST1, BST2, NURSE1, NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE5, CN1, NURSE6, SW1, MO3, HST2, DFT2, GER1, GER2, DLN, Director1 |

| M | Faulty system which is open to abuse | Pitfalls in the current system at MDH that render the system vulnerable and open to abuse | HST1, NURSE1, NURSE4, DFT1, NURSE5, CN2, NURSE6, SW1, BST3, HST2, DFT2, GER1, GER2, DLN, Director1 |

| N | LTC cases concentrated in medical arena | The prevalence of long-term patients present in the medical arena as opposed to other specialties | MO2, MO1, BST2, HST1, BST3, HST2, DNM1 |

| O | A&E gatekeeping failure | Pitfalls in A&E triage and admitting system | HST1, NURSE4, NURSE6, BST3, HST2, DLN, DNM1, Director1, BMU |

| P | Delayed discharges and bed-blocking | The impact of delays in patient discharge on the prevalence of bed-blocking in MDH, and the relationship between the two | BST1, NURSE4, CN1, NURSE6, BST3 |

| Q | Link between COVID-19 and nosocomial infections | The relationship between delays resulting from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and nosocomial infections | MO2, MO1, HST2 |

| R | Link between re-admissions and LTC cases | The link between patient re-admission and system abuse and the creation of LTC cases | BST2, NURSE2, NURSE5, DLN |

| S | A lack of proper admission protocol | BST1 | |

| T | Management shortcomings linked to political interference | Hospital management shortcomings related to the discharge process | BST1, DFT1, NURSE5, HST2, DFT2 |

| U | Initiatives proposed to decrease delayed discharges | Initiatives put forward by stakeholders to decrease the impact and/or incidence of delays in patient discharge | MO2, BST2, HST1, NURSE1, NURSE2, NIRSE3, NURSE4, DFT1, NURSE5, CN1, CN2, NURSE6, NURSE7, SW1, MO3, BST3, HST2, DFT2, GER1, GER2, DLN, BMU, DNM2, DNM1, Director1 |

| V | Management adhering to its own protocols | Lack of managerial support as related to health professionals strictly adhering to hospital protocols | BST1, CN1, NURSE7, SW1, DFT2 |

| W | Age as a factor impacting delayed discharges | Patient’s age as a factor impacting delayed discharges | NURSE1, NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE4, CN1, NURSE5, CN2, NURSE6, SW1, MO3, HST2, DLN |

| X | Bed-blocking as related to nursing home unavailability | The impact of delays/shortages of nursing home bed space on delays in patient discharge in MDH | NURSE1, NURSE3, CN1, CN2, BMU |

| Y | Profession-specific tasks linked to delays | The impact of profession-specific tasks on delays in the patient’s journey through the hospital system | NURSE2, DFT1, NURSE5, HST2, GER2 |

| Z | Procedural delays as being specialty-specific | Procedural delays as being more prevalent in certain specialties compared with others | NURSE2, NURSE4 |

| AA | Procedural delays as linked to nosocomial infections | Link between procedural delays and the incidence of nosocomial infections | NURSE2, NURSE3, NURSE4, DLN |

| BB | LTC beds/rehab bed availability as related to delayed discharges | The link between bed availability in rehab/LTC facilities as related to delays in discharge | NURSE2, NURSE4, NURSE5, MO3, BST3, DFT2, GER1, GER2, BMU, DNM2, DNM1 |

| CC | A&E overcrowding as related to delayed discharges | The impact of delays in discharge on A&E overcrowding | NURSE3, MO3, DNM2, BMU |

| DD | Shortcomings of hospitality lounge to counteract delayed discharges | Problems that prevent the discharge lounge from being more effective as an agent of delay prevention | NURSE3, CN1 |

| EE | Delay problems on day of discharge | Problems on the ward that prevent timely discharge on the day of discharge | NURSE4, CN1, CN2, NURSE7, HST2, DLN, BMU, DNM2 |

| FF | System flaws that extend patients’ length of stay | System pitfalls and imperfections that unnecessarily extend patients’ length of stay and results in delays in discharge | DFT1, CN1, NURSE6, NURSE7, SW1, BST3, GER1, SW2, DLN |

| GG | MMSE imperfect as a tool | MMSE tool as being prone to misleading results | DFT1, SW1, SW2, DLN |

| HH | Role confusion | Confusion and inconsistencies regarding health professionals’ knowledge about each other’s roles and job descriptions | SW1, DFT2 |

| II | Delayed discharges as related to medical professionals working solo | Lack of teamwork between health professionals | NURSE5, DFT2 |

| JJ | LTC problems leading to staff alienation/demotivation | Staff alienation/demotivation as related to work life becoming unchallenging and boring/repetitive | CN2, NURSE6, DLN |

| KK | Inter-professional collaboration | Teamwork and collaboration between different health professionals | SW1, DFT2, SW2, GER1, GER2, DNM1, DNM2 |

| LL | Relocation problems | Shortcomings related to the relocation of patients from one LTC facility to another in relation to the impact on MDH | NURSE6, SW1, BST3, GER2 |

| MM | Lack of proper resources | Shortage of resources that increases delays in discharge | MO3, SW2, GER2, DLN, DFT2 |

| NN | System abuse by staff | Staff abusing the system so as to avoid work tasks | DNM2 |

| OO | Treatment in the community | Treatment administration (intravenous) in the community by the HAT team | Director1 |

References

- Buchanin, D. Pure plays and hybrids: Acute trust management profile and capacity. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2013, 18, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ltchenberg, F.R.; Pettersson, B. The impact of pharmaceutical innovation on longetivity and medical expenditure in Sweden (1997–2010): Evdience from longitudinal, disease level data. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2014, 23, 239–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, R.; Scanelli, G.; Tragnone, A.; Lolli, A.; Kalfus, P.; Baldini, A.; Ghedini, T.; Bombarda, S.; Fiadino, L.; Di Ciommo, S. Difficult hospital discharges in internal medicine wards. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2007, 2, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugaland, K.; Aase, K.; Waring, J. Hospital discharge of the elderly--an observational case study of functions, variability and performance-shaping factors. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Henderson, D.; Lemmon, E.; Partignani, P. COVID-19 Mortality and Long-Term Care: A UK Comparison; Econ Res Reports 2020; Internatio: Lisle, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza Giraldo, D.; Navarro, A.; Sanchez-Quijano, A.; Villegas, A.; Asencio, R.; Lissen, E. Impact of delayed discharge for nonmedical reasons in a tertiary hospital internal medicine department. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2012, 212, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinarachchi, K.H.; Ibrahim, I.R.; Keegan, B.C.; Mathialagan, R.; McGourty, J.C.; Phillips, J.R.N.; Myint, P.K. Delayed transfer of care from NHS secondary care to primary care in England: Its determinants, effect on hospital bed days, prevalence of acute medical conditions and deaths during delay, in older adults aged 65 years and over. BMC Geriatr. 2009, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micallef, A.; Buttigieg, S.C.; Tommasselli, G.; Garg, L. Defining delayed discharges of inpatients and their impact on acute hospital care: A scoping review. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, C.R.; Healy, J.; Thomas, A.; Seargeant, J. Older patients and delayed discharge from hospital. Health Soc. Care Community 2000, 8, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Wong, B.; Wijeysundera, H.C. Root causes for delayed hospital discharge in patients with ST-segment Myocardial Infarction (STEMI): A qualitative analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2015, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edirimanne, S.; Roake, J.A.; Lewis, D.R. Delays in discharge of vascular surgical patients: A prospective audit. ANZ J. Surg. 2010, 80, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant, J.; Abela, G.P.; Farrugia, D. Delayed discharges and unplanned admissions from the day care unit at Mater Dei hospital, Malta. Malta Med. J. 2015, 27, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, D.E.; Pacyna, J.E.; Gillard, K.L.; Carter, L.C. Tracking Discharge Delays: Critical First Step Toward Mitigating Process Breakdowns and Inefficiencies. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2016, 31, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryson, D. Care homes shouldn’t profit from delays in assessing their residents for discharge from hospital. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2011, 343, d6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, R.T.; Drew, J.C.; Galland, R.B. A waiting list to go home: An analysis of delayed discharges from surgical beds. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2006, 88, 650–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeiro, F.; Roberts, K.; Gray, A.M.; Leal, J. Delayed hospital discharges of older patients: A systematic review on prevalence and costs. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigal, J.; Park, B.; Bramante, C.; Nordgaard, C.; Menk, J.; Song, J. Homelessness and discharge delays from an urban safety net hospital. Public Health 2014, 128, 1033–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philp, I.; Mills, K.A.; Thanvi, B.; Ghosh, K.; Long, J.F. Reducing hospital bed use by frail older people: Results from a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Integr. Care 2013, 13, e048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, A.D.; Oldham, J.B. Delayed discharge from rehabilitation after brain injury. Clin. Rehabil. 2006, 20, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, L. How one neurology department improved on early hospital discharges. Neurol. Today 2013, 13, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, K.S.; Corso, P.; Bacon, S.; Jenq, G.Y. Using the red/yellow/green discharge tool to improve the timeliness of hospital discharges. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. patient Saf. 2014, 40, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Healthcare Reource Statistics—Beds. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Healthcare_resource_statistics_-_beds (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Azzopardi, N.; Calleja, N.; Buttigieg, S.C.; Merkur, S. Malta Health Systems Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2017, 19, 1–137. [Google Scholar]

- El-Eid, G.R.; Kaddoum, R.; Tamim, H.; Hitti, E.A. Improving hospital discharge time: A successful implementation of six sigma methodology. Medicine 2015, 94, e633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinkels, A.; Mitchell, T. Delayed transfer from hospital to community settings: The older person’s perspective. Health Soc. Care Community 2009, 17, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.; Gilligan, P.; Obu, D.; O’Kelly, P.; O’Hea, E.; Lloyd, C.; Kelada, S.; Heffernan, A.; Houlihan, P. “Delayed discharges and boarders”: A 2-year study of the relationship between patients experiencing delayed discharges from an acute hospital and boarding of admitted patients in a crowded ED. Emerg. Med. J. 2016, 33, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, P.; Patel, J.H.; Kordbacheh, T.; Laskar, N.; Harbord, M. In-depth analysis of delays to patient discharge: A metropolitan teaching hospital experience. Clin. Med. 2012, 12, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, I.M.; Williams, D.T.; Pollock, R.; Amir, F.; Liam, M.; Foong, K.S.; Whitaker, C.J. Delay in discharge and its impact on unnecessary hospital bed occupancy. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devapriam, J.; Gangadharan, S.; Pither, J.; Critchfield, M. Delayed discharge from intellectual disability in-patient units. Psychiatr. Bull. 2014, 38, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S. Qualitative Research and Case Study Application in Education; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yazan, B. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam and Stoke. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Heppner, P.P.; Kivilghan, D.M.; Wampold, B.E. Research Design in Counseilling, 2nd ed.; Brooks Cole: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.E.; Knox, S.; Thompson, B.J.; Williams, E.N.; Hess, S.A.; Ladany, N. Consensual qualitative research: An update. J. Counseilling Psychol. 2005, 52, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, E.; Hudson, E.; Royas-Garcia, A.; Turner, S.; Thomas, J.R.R. Impact and experiences of delayed discharge: A mixed-studies systematic review. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, C.A.; Raibee, F. “A question of access”—An explanation of the factors influencing the health of young men aged 15-19 living in Corby and their use of health care services. Health Educ. J. 2001, 60, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.M.; Draper, A.K.; Dowler, E. Short cuts to safety: Risk and “rules of thum” in accounts of food choice. Health Risk Soc. 2003, 5, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, R. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, R.A.; Cosey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H. Thematic Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.R. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trusthworthyness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attride-Sterling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, G. Validity, trusthworthyness and rigor: Quality and the idea of qualitative research. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2006, 53, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for in-terviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambani, R.; Okafor, B. Evaluation of Factors Delaying Discharge in Acute Orthopedic Wards: A Prospective Study. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2008, 34, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henwood, M. Effective partnership working: A case study of hospital discharge. Helath Soc. Care Community 2006, 14, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.; Epstein, D.; Rozen, M.; Miskin, A.; Halberthal, M.; Mekel, M. Delayed discharges from a tertiary teaching hospital in Israel–incidence, implications, and solutions. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2020, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everall, A.C.; Guilcher, S.J.T.; Cadel, L.; Asif, M.; Li, J.; Kuluski, K. Patient and craegiver experience with delayed discharge from a hospital setting: A scoping review. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redwood, S.; Simmonds, B.; Fox, F.; Shaw, A.; Neubauer, K.; Purdy, S.B.H. Consequences of “conversations not had”: Insights into failures in communication affecting delays in hospital discharge for older people living with frailty. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2020, 25, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Young, L.; Ou, L.; Santiano, N. Discharge delay in acute care: Reasons and determinants of delay in general ward patients. Aust. Health Rev. 2009, 33, 513–521. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, H.; Wu, R.C.; Tomlinson, G.; Caesar, M.; Abrams, H.; Carter, M.W.; Morra, D. How much do operational processes affect hospital inpatient discharge rates? J. Public Health 2009, 31, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, M.; Townsend, J. Delayed hospital discharge in England and Scotland: A comparative study of policy implementation. J. Integr. Care 2009, 17, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towle, R.M.; Hussain, Z.B.M.; Chew, S.M. A descriptive study on reasons for prolonged hospital stay in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 2307–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeiro, F.; Leal, J.; Gray, A.M. The impact of social isolation on delayed hospital discharges of older hip fracture patients and associated costs. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).