Translating Strategies into Tactical Actions: The Role of Sourcing Levers in Healthcare Procurement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purchasing Strategies and Sourcing Levers

1.2. Health Sector Exceptionalism and PPI Purchasing

2. Methods

2.1. Interview Guide

2.2. Respondent Selection

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sourcing Levers

3.2. Patterns of Sourcing Levers Adopted by Healthcare Organizations

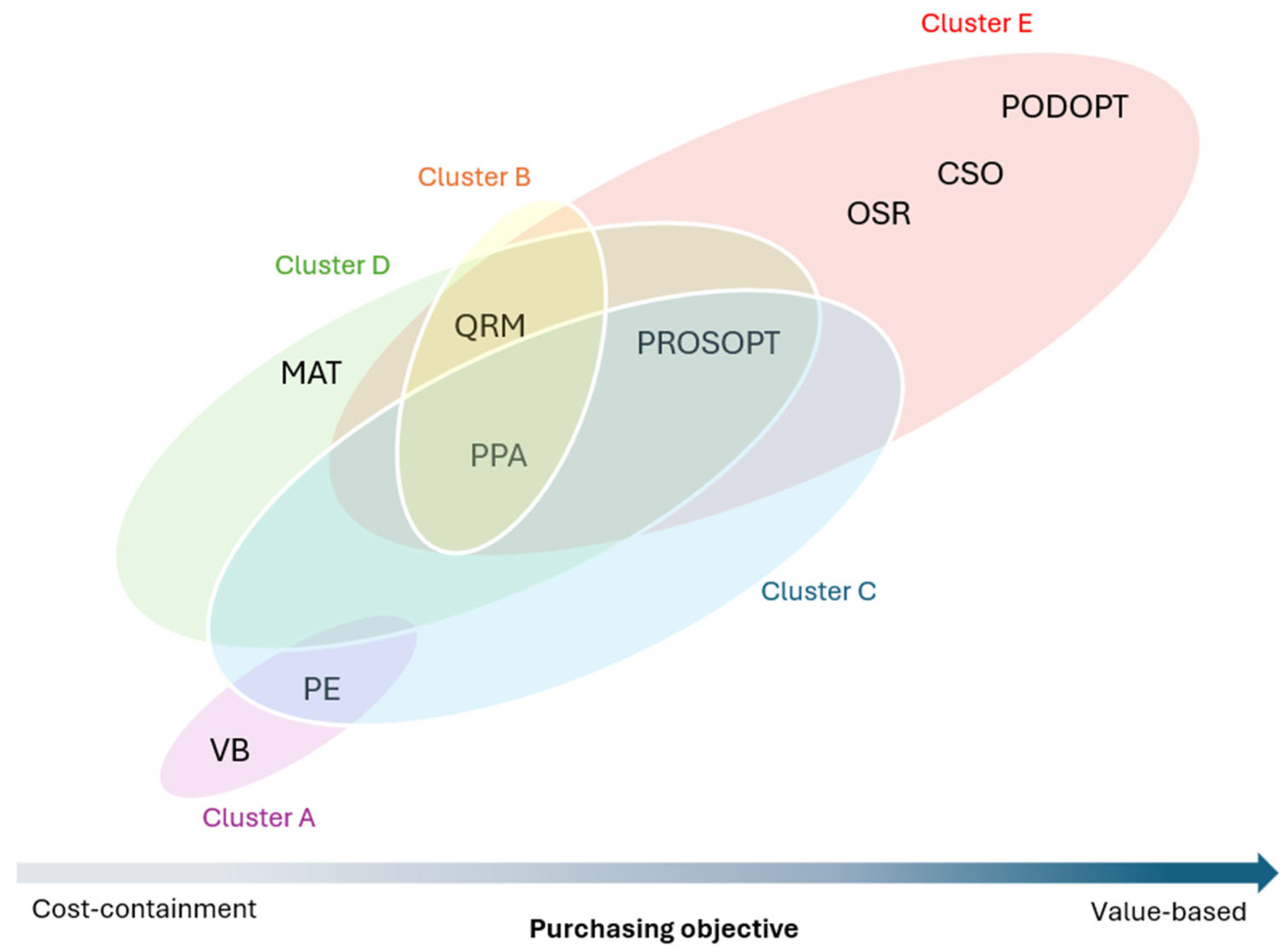

- Cluster A—total cost of ownership. The adoption of PE and VB jointly was identified in organizations that prioritize a cost structure. This is the case of BRA and CAN2, which are searching to obtain economies of scale and cost-containment. It is worth mentioning that this sourcing level is achieved through different manners in these organizations. While BRA has a public tender system, in which the supplier awarding and supplier selection phases are designed to match these requirements, CAN2 uses a GPO (group purchasing organization) to leverage volumes purchased to reach such an end.

- Cluster B—managing the internal process. This set of sourcing levers (QMR and PPA) is associated with activities conducted before the procurement process actually takes place. This association of sourcing levers can provide a solid basis for preparing the procurement process. Organizations in this cluster are engaged in managing the internal stakeholders’ dynamic that brings complexity to PPI purchasing (ENG, CAN3, FRA1). Therefore, the focus lies on the internal processes conducted to acquire these medical items. This cluster of sourcing levers can support aligning different stakeholders’ perspectives and prevent maverick buying, for example.

- Cluster C—supply chain optimization. It brings sourcing levers together that are inserted at the intersection of other clusters “PPA, PE, PROSOPT”. It is possible to observe that organizations adopting this set of sourcing levers are concentrated on making their supply chain processes associated with these suppliers more efficient (USA1, USA2, USA3, FRA2). These organizations shift from the procurement process’s internal focus to an external perspective. The main goal is to support the procurement process by optimizing it. These organizations use a set of techniques, such as consigned inventories, for example.

- Cluster D—ensuring suppliers’ services. This cluster consists of the following set of sourcing levers “PPA, QMR, PROSOPT, MAT”. The organizations that showed this pattern of sourcing levers adopted are NEW, BEL1, and BEL2. This set of sourcing levers seems to be essential for ensuring the suppliers’ services associated with PPI purchasing. The main purchasing objective of these organizations is to ensure supply availability and the associated services that the suppliers can provide them. For example, NEW depends on a small supply market to provide services, such as training for new products acquired. Therefore, these sourcing levers appear to support leveraging supply availability in scarce supply markets.

- Cluster E—value-based procurement. Organizations belonging to this cluster presented the following sourcing levers in common: “PROSOPT, PODOPT, OSR, PPA, QRM, and CSO”. Organizations that showed this sourcing lever pattern include CAN1, DEN, and NOR. When used jointly, these sourcing levers appear to support the search for better outcomes and improved value to the patients, as the main feature of the procurement process is to promote better solutions to patients.

4. Discussion

4.1. Bridging Strategy and Tactical Activities

4.2. Towards Value-Based Procurement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Interview Guide |

- Part I—Organization description

- Could you describe/verify your organization, please?

- Number of hospitals:

- Number of employees:

- Part II—Supply management

- From a recent typical purchasing project PPI (within the last 2 years), could you describe the following:

- ☐

- The nature of the product or equipment that was acquired? (for example, for cardiology, orthopedic, etc.)?

- ☐

- How many hospitals were involved in this project?

- ☐

- How many surgeons use this product?

- Could you please describe the contracting process?

- ☐

- What were the main steps?

- ☐

- Who was the leader of the project?

- ☐

- How long did the whole process take?

- Could you please describe the purchasing strategy adopted?

- ☐

- How was it formulated?

- ☐

- What is the orientation of the strategy?

- ☐

- What are the main purchasing objectives?

- Could you please explain how the purchasing strategy is deployed in tactical activities?

- Describe the stakeholders involved in this project, please. Are these stakeholders implying to implement the contract or to influence other physicians to use the product on the contract?

- ☐

- What positions do they occupy?

- ☐

- How many physicians were there?

- ☐

- What criteria were used to recruit these stakeholders?

- ☐

- What was the role of these stakeholders in the process?

- Describe the criteria surgeons use to justify their choice of products/equipment, please.

- ☐

- Is the price of these products/equipment part of the criteria considered?

- ☐

- Do surgeons know the prices of the items they use?

- What are the main characteristics of the contract for this project?

- ☐

- Duration of the contract?

- ☐

- Single or multiple supplier? What are the main explanations justified in one strategy or another?

- ☐

- How do you split your supply needs among existing suppliers?

- ☐

- What were the guidelines/constraints of the legal framework imposed in order to reach an agreement?

- How does this agreement take into consideration future technological developments?

- What are the indicators used to judge the success of PPI projects?

- ☐

- How often are they measured?

- ☐

- Are these indicators shared with stakeholders?

- How do you control these measures to ensure the achievement of initial objectives?

- Part III—Physicians’ and patients’ interests

- 11.

- Are training and implementation costs taken into consideration when purchasing new products and equipment?

- ☐

- In the process of choosing a PPI, could you buy a product that is more expensive, but which could, for example, reduce the average length of stay for surgery from five to two days?

- 12.

- How are patients’ particular needs addressed by surgeons based on products and equipment on contract?

- 13.

- Are surgeons considered self-employed or employees from the hospital perspective?

- ☐

- Do you have a gainsharing program with surgeons?

- ☐

- Could you please describe this program?

- 14.

- Is the information supporting the decision process to acquire equipment/products easily accessible?

- ☐

- Do stakeholders dispute the impartiality of this information?

- 15.

- What mechanisms are in place to integrate funding provided by suppliers for research?

- Part IV—Supplier relationship

- 16.

- The following questions deal with supplier relationships.

- ☐

- Which percentage of PPIs are on consignment?

- ☐

- Do suppliers manage their consigned inventory? (i.e., periodic inventory management, cycle counting)

- ☐

- Have you concluded partnership between your institution and suppliers?

- ☐

- If you have such partnerships, what are the main characteristics of these partnerships? (i.e., exclusivity, duration of the agreement, sharing of earnings, etc.)

- ☐

- What are the main success factors that are the basis for the partnership conclusion?

- ☐

- What are the main enabling elements that supported the development of the partnership?

- ☐

- Are such partnerships possible though a group purchasing organization?

- ☐

- Are there legal constraints that limit the implementation of such partnerships?

- ☐

- How many of these partnerships were successful?

- ☐

- How could you improve these partnerships?

- 17.

- How do you address the evolution of the supplier’s market (suppliers decline, new entrants)?

- Part V—Conclusions and key lessons

- 18.

- Are there any other initiatives to lower operating costs, such as inventory management standardization of medical supplies?

- ☐

- Are surgeons committed to lower operating costs? If so, could you explain, please?

- 19.

- To conclude, in your opinion, what are the main strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities to improve PPI management?

- ☐

- What are the success factors for PPI management?

- ☐

- What are the main barriers to PPI management?

References

- Hesping, F.H.; Schiele, H. Matching tactical sourcing levers with the Kraljič matrix: Empirical evidence on purchasing portfolios. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 177, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, K.; Schneller, E.S. Hospitals’ strategies for orchestrating selection of physician preference items. Milbank Q. 2007, 85, 307–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, J.; Menzies, L.; Michaelides, R. The long shadow of public policy; Barriers to a value-based approach in healthcare procurement. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2017, 23, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, G. Value-based procurement: Canada’s healthcare imperative. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2016, 29, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, L.R.; Housman, M.G.; Booth, R.E.; Koenig, A.M. Physician preference items: What factors matter to surgeons? Does the vendor matter? Med. Devices 2018, 11, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atilla, E.A.; Steward, M.; Wu, Z.; Hartley, J.L. Triadic relationships in healthcare. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesping, F.H.; Schiele, H. Purchasing strategy development: A multi-level review. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2015, 21, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiele, H.; Horn, P.; Vos, G.C.J.M. Estimating cost-saving potential from international sourcing and other sourcing levers. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2011, 41, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, K.; Kässer, M.; Blome, C.; Foerstl, K. How to achieve cost savings and strategic performance in purchasing simultaneously: A knowledge-based view. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2020, 26, 100534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Finkelstein, A.; Sacarny, A.; Syverson, C. Health Care Exceptionalism? Performance and Allocation in the US Health Care Sector. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 2110–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, D.A.; Laric, M.V. Value chains in health care. J. Consum. Mark. 2004, 21, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger-Trayner, E.; Fenton-O’Creevy, M.; Hutchinson, S.; Kubiak, C.; Wenger-Trayner, B. Learning in Landscapes of Practice: Boundaries, Identity, and Knowledgeability in Practice-Based Learning; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rink, D.R. The product life cycle in formulating purchasing strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1976, 5, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, D.; Zundel, M. Recovering the Divide: A Review of Strategy and Tactics in Business and Management. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sull, D. Closing the Gap Between Strategy and Execution. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2007, 48. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/closing-the-gap-between-strategy-and-execution/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Sull, D.; Homkes, R.; Sull, C. Why strategy execution unravels—And what to do about it. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 93, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schneller, E.S.; Abdulsalam, Y.; Conway, K.; Eckler, J. Strategic Management of the Health Care Supply Chain; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ateş, M.A.; van Raaij, E.M.; Wynstra, F. The impact of purchasing strategy-structure (mis)fit on purchasing cost and innovation performance. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2018, 24, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.R.; Narasimhan, R. Purchasing and Supply Management: Future Directions and Trends. Int. J. Purch. Mater. Manag. 1996, 32, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benito, J. Supply strategy and business performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2010, 30, 774–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiele, H. Supply-management maturity, cost savings and purchasing absorptive capacity: Testing the procurement–performance link. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2007, 13, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsalam, Y.; Gopalakrishnan, M.; Maltz, A.; Schneller, E. The impact of physician-hospital integration on hospital supply management. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 57, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.R. The Healthcare Value Chain; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sisk, S.; Schmidt, R.N.; House, M.E.; Dayama, N.; Posey, M. Reducing supply costs in healthcare through the utilization of group purchasing organizations (GPOs). J. Bus. Behav. Sci. 2021, 33, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell-Inderst, P.; Mayer, J.; Lauterberg, J.; Hunger, T.; Arvandi, M.; Conrads-Frank, A.; Nachtnebel, A.; Wild, C.; Siebert, U. Health technology assessment of medical devices: What is different? An overview of three European projects. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, D.T.; Boyle, E.M., Jr.; Benjamin, E.M. Addressing the imperative to evolve the hospital new product value analysis process. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunger, T.; Schnell-Inderst, P.; Sahakyan, N.; Siebert, U. Using Expert Opinion in Health Technology Assessment: A guideline review. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2016, 32, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellram, L.M. A Framework for Total Cost of Ownership. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 1993, 4, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennestrì, F.; Lippi, G.; Banfi, G. Pay less and spend more—The real value in healthcare procurement. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handfield, R.B.; Venkitaraman, J.; Murthy, S. Do prices vary with purchase volumes in healthcare contracts? J. Strateg. Contract. Negot. 2017, 3, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.C. Value-Based Purchasing For Medical Devices. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsalam, Y.J.; Schneller, E.S. Of barriers and bridges: Buyer–supplier relationships in health care. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsalam, Y.; Schneller, E. Hospital Supply Expenses: An Important Ingredient in Health Services Research. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2017, 76, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.R.; Lee, A. Hospital purchasing alliances: Utilization, services, and performance. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, M.; Choi, T.Y.; Li, M. Qualitative case studies in operations management: Trends, research outcomes, and future research implications. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.B.; Sakakibara, S.; Schroeder, R.G.; Bates, K.A.; Flynn, E.J. Empirical research methods in operations management. J. Oper. Manag. 1990, 9, 250–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Hubermann, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Linneberg, M.S.; Korsgaard, S. Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qual. Res. J. 2019, 19, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Riege, A.M. Validity and Reliability Tests in Case Study Research: A Literature Review with “Hands-On” Applications for Each Research Phase. Qual. Mark. Res. 2003, 6, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, S. An Evaluation of Hospital-Based Health Technology Assessment Processes in the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, B.S.; Kuhn, L.P. Sustaining savings. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2009, 63, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, L.R.; Muller, R.W. Hospital-Physician Collaboration: Landscape of Economic Integration and Impact on Clinical Integration. Milbank Q. 2008, 86, 375–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsali, S.; Pezzoni, M.; Krafft, J. Healthcare Procurement and Firm Innovation: Evidence from AI-powered Equipment; GREDEG Working Papers 2023-05; Groupe de REcherche en Droit, Economie, Gestion (GREDEG CNRS) Université Côte d’Azur: Nice, France, 2023; Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/gre/wpaper/2023-05.html (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Khan, F.S.; Masum, A.A.; Adam, J.; Karim, M.R.; Afrin, S. AI in Healthcare Supply Chain Management: Enhancing Efficiency and Reducing Costs with Predictive Analytics. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2024, 6, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamato, V.; Tricase, C.; Faccilongo, N.; Iacoviello, M.; Pange, J.; Marengo, A. Machine Learning for Evaluating Hospital Mobility: An Italian Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sourcing Levers | Description |

|---|---|

| Volume bundling (VB) | Consolidation and volume leverage |

| Price evaluation (PE) | Focused on price goals, and cost structure |

| Extension of supply base (EXT) | Increase the number of suppliers |

| Product optimization (PODOPT) | Modifying/improving products and materials |

| Process optimization (PROSOPT) | More efficient and effective processes with suppliers |

| Optimization of supply relationships (OSR) | Developing and maintaining effective buyer–supplier relationships |

| Category-spanned optimization (CSO) | Orchestrating trade-offs among sourcing categories |

| Respondents | Country | % GPD Healthcare | Number of Hospitals | Nature of the Products | Nature of the Healthcare Sector | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAN1 | Canada | 11.7% | 1 | Cardiac stents | Public | Innovation director |

| CAN2 | 22 | Cardiology implants | Public | Procurement manager | ||

| CAN3 | 11 | Angio radiology | Public | Procurement manager | ||

| USA1 | United States | 17.8% | 28 | Vascular grafts | Private | Materials manager |

| USA2 | 6 | Spine metal fix | Private | Category manager | ||

| USA3 | 3 | Cardiovascular Implants | Private | Category manager | ||

| BEL1 | Belgium | 11.1% | 1 | Orthopedic surgery | Mostly Public | Procurement manager |

| BEL2 | 7 | Pacemakers | Mostly Public | Procurement manager | ||

| FRA1 | France | 12.4% | 150 | Orthopedic prosthesis | Mostly Public | Procurement manager |

| FRA2 | 5 | Rhythmology devices | Mostly Public | Procurement manager | ||

| ENG | England | 11.9% | 342 | Orthopedics, Hip joints and Knee joints | Public | Procurement manager |

| DEN | Denmark | 10.8% | 10 | Orthopedics, Knee implants | Public | Procurement manager |

| NOR | Norway | 10.1% | 20 | Pacemakers | Public | Project manager |

| NEW | New Zealand | 9.7% | 14 | Pacemakers | Mostly Public | Procurement manager |

| BRA | Brazil | 9.6% | 1 | Orthopedics, and cardiology | Public | Procurement manager |

| Sourcing Levers | Description | Enhancement Thesis Related |

|---|---|---|

| Volume bundling (VB) * | Consolidation and volume leverage | Specified in procuring through GPOs (group purchasing organizations) |

| Price evaluation (PE) * | Focus on price goals and cost structure | Specified in limiting physicians’ choices to achieve cost-containment |

| Product optimization (PODOPT) * | Modify/improve products and materials | Specified in patient-centric and value |

| Process optimization (PROSOPT)* | More efficient and effective processes with suppliers | Specified in collaborating with suppliers and services provided |

| Optimization of supply relationships (OSR) * | Develop and maintain effective buyer–supplier relationships | Specified in effectively engaging the supplier in the procurement process |

| Category-spanned optimization (CSO) * | Orchestrate trade-offs | Specified in orchestrating costs and value |

| Pre-purchasing activity (PPA) ** | Prepare the procurement process | Conduct a detailed analysis of the procurement needs and requirements and the supply market |

| Quality meeting requirements (QMR) ** | Engage internal stakeholders and meet requirements | Standardization procedures to manage the physicians’ preferences |

| Maintaining the supply market (MAT) ** | Ensure the availability of supplies | Consider the continuity of the medical supplies and the services provided |

| Sourcing Levers | CAN1 | DEN | NOR | NEW | BEL1 | BEL2 | USA1 | USA2 | USA3 | FRA2 | CAN2 | ENG | BRA | FRA1 | CAN3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product optimization (PODOPT) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Category-spanned optimization (CSO) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Optimization of supply relationships (OSR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Process optimization (PROSOPT) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Maintaining the supply market (MAT) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Pre-purchasing activity (PPA) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Quality meeting requirements (QMR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Volume bundling (VB) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Price evaluation (PE) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belotti Pedroso, C.; Schneller, E.; Rebolledo, C.; Beaulieu, M. Translating Strategies into Tactical Actions: The Role of Sourcing Levers in Healthcare Procurement. Hospitals 2025, 2, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals2020012

Belotti Pedroso C, Schneller E, Rebolledo C, Beaulieu M. Translating Strategies into Tactical Actions: The Role of Sourcing Levers in Healthcare Procurement. Hospitals. 2025; 2(2):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals2020012

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelotti Pedroso, Carolina, Eugene Schneller, Claudia Rebolledo, and Martin Beaulieu. 2025. "Translating Strategies into Tactical Actions: The Role of Sourcing Levers in Healthcare Procurement" Hospitals 2, no. 2: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals2020012

APA StyleBelotti Pedroso, C., Schneller, E., Rebolledo, C., & Beaulieu, M. (2025). Translating Strategies into Tactical Actions: The Role of Sourcing Levers in Healthcare Procurement. Hospitals, 2(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals2020012