Abstract

Green development serves as the foundation for high-quality development. As one of the most commonly used macroeconomic regulation policies, taxation is a crucial component of the modernization of the national governance system and governance capacity, playing an irreplaceable role in accelerating the comprehensive green transformation of economic and social development. Based on panel data from 30 provinces (municipalities, autonomous regions) from 2011 to 2021, this paper empirically analyzes the impact of green taxation on green transformation. The study finds that green taxation can significantly promote urban green transformation, and there is significant regional heterogeneity in the impact of green taxation on urban green transformation. Mechanism tests further reveal that green taxation influences the scale of urban investment platform debt, thereby driving urban green transformation.

1. Introduction

With the acceleration of urbanization and industrialization, environmental issues in China have become increasingly prominent. China’s traditional high-emission, high-energy-consumption, and high-pollution economic model has achieved rapid economic growth at the expense of the environment. For example, the energy structure dominated by coal and the sharp increase in the number of motor vehicles have led to continuous deterioration of air quality and frequent occurrence of haze weather; a large amount of industrial wastewater and domestic sewage without effective treatment are directly discharged into rivers and lakes, seriously threatening the balance of water ecosystem and the safety of residents’ drinking water; the heavy metal pollution generated by industrial activities, the unreasonable use of pesticides and fertilizers in agricultural production, and the improper disposal of solid waste have led to reduced crop yields, decreased quality, and even entering the human body through the food chain, endangering human health. This series of environmental problems directly affect the healthy life of the people.

To explore a more balanced development model, the report of the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China [1] in November 2012 proposed “focusing on promoting green development, circular development, and low-carbon development”. In October 2015, the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee [2] first introduced the “Five Development Concepts” of innovation, coordination, green development, openness, and sharing, charting the path forward for China’s economic and social development. “Green development” has since become an important national development strategy. In October 2022, the report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China [3] called for “accelerating the green transformation of development models” and emphasized that “promoting the greening and low-carbonization of economic and social development is a key link in achieving high-quality development”. In January 2024, General Secretary Xi Jinping stated in a speech during the 11th collective study session of the Political Bureau of the 20th Central Committee [4] that “green development is the defining feature of high-quality development, and new quality productive forces are inherently green productive forces. We must accelerate the green transformation of development models”, elevating “green development” to a new theoretical height. In August 2024, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the Opinions on Accelerating the Comprehensive Green Transformation of Economic and Social Development [5], proposing to “integrate the requirements of green transformation into the overall economic and social development, covering all aspects, fields, and regions” and to “accelerate the coordinated digital and green transformation, promoting the deep integration of industrial digitalization, intelligence, and greening… to achieve digital technology empowering green transformation”. In March 2025, the government work report [6] called for “coordinated efforts to reduce carbon emissions, cut pollution, expand green development, and promote growth, accelerating the comprehensive green transformation of economic and social development”.

Currently, China is transitioning from a traditional development model to a scientific and high-quality development model. On the one hand, China is comprehensively utilizing administrative, legal, and economic measures to explore and practice green transformation. Among various policy tools, taxation, as a lever for government macroeconomic regulation, plays an irreplaceable role in promoting green transformation. The implementation of the Environmental Protection Tax in 2018 marked the standardization of China’s use of taxation to promote environmental protection. Green taxation directly increases the production costs of polluters. Driven by profit maximization, enterprises will strive to reduce pollution emissions during production and circulation. Meanwhile, tax costs and preferential policies will guide some enterprises to transform, adopting energy-saving, environmentally friendly technologies and green production, thereby promoting green transformation. On the other hand, urban investment platforms, as the main force in local infrastructure construction, are seeing their reasonably expanded debt scale become an important lever for urban green transformation. In terms of fundraising, urban investment platforms gather substantial social capital through various debt-financing methods such as green bond issuance and policy bank loans, laying a solid material foundation for green transformation. In guiding industrial layout, urban investment platforms can direct funds to green industries such as energy conservation, environmental protection, and new energy in line with the strategic planning of urban green transformation during the debt-financing process. In terms of sustainable development, urban investment platforms align debt financing with the medium- and long-term planning of urban green transformation, rationally arranging the maturity structure of debt to ensure the use of debt funds matches the phased goals of urban green transformation, providing a guarantee for the sustainability of urban green transformation.

2. Literature Review

At the beginning of the 20th century, British economist Pigou pointed out in his book “Welfare Economics” [7] that if a company engages in production and business activities without bearing the negative impact of its actions on the environment and society (such as excessive consumption of resources and pollution emissions), it will lead to a decrease in market efficiency in resource allocation and cause irreversible damage to the natural environment, known as negative externalities. Due to the fact that enterprises aim to maximize economic benefits and market mechanisms themselves are difficult to effectively solve such externalities, Pigou proposed based on his analysis of market failure that the government should impose a tax on enterprises that generate negative externalities, which is exactly equal to the marginal external costs caused by their activities, that is, the additional damage they bring to society. The purpose of this taxation behavior is to internalize external costs, so that the private costs of enterprises reflect the real social costs, thereby guiding the market to achieve better resource allocation results. This tax was later known as the “Pigouvian tax”. The concept of Pigouvian taxation has laid an important theoretical foundation for modern environmental economic policies. Since the 1970s, in the face of increasingly severe environmental challenges, developed countries such as Europe and America have gradually applied the principles of “polluter pays” and “cost internalization” to environmental policies.

The core idea of Pigouvian taxation, which aims to internalize external costs through taxation, provided a crucial economic tool for addressing environmental issues in later generations. On the basis of Pigou’s theory, countries began to explore the use of tax measures to regulate environmental behavior. In terms of conceptual expression, early academic discussions and policy practices often used the relatively broad term ‘environmental taxation’. With the deepening of global understanding of sustainable development and the promotion of ecological civilization construction, the concept of “environmental taxation” has gradually been replaced by “green taxation” with richer connotations and more emphasis on environmental protection, and became a research hotspot in the 1990s.The International Tax Glossary defines “green taxation” as tax reductions or exemptions enjoyed by taxpayers who invest in pollution control and environmental protection, as well as taxes levied on taxpayers who generate or emit pollutants. At present, Chinese scholars still have different views on the definition of green taxation. For example, Rao Lixin argued that the connotation of green taxation should include taxes on products and users that cause environmental pollution, as well as preferential policies in various tax categories aimed at environmental protection [8]. Zhang Aizhu believed that narrow green taxation refers solely to the Environmental Protection Tax, while broad green taxation encompasses all tax categories and items related to environmental protection in the tax system [9]. Deng Xiaolan proposed that green taxation can be divided into small, medium, and large scopes. Small-scope green taxation refers specifically to the Environmental Protection Tax levied for environmental protection. Medium-scope green taxation includes the Environmental Protection Tax (or pollution discharge fees) and related tax categories with green attributes but not directly aimed at environmental protection. Large-scope green taxation encompasses all taxes and fees levied on enterprises causing environmental pollution [10]. Ma Caichen and Zhao Di pointed out that, in addition to pollution-related Environmental Protection Taxes, energy taxes and transportation taxes are also important components of the green taxation system [11]. Deng Liping argued that China currently adopts a “multi-tax co-governance” green taxation system, with the Environmental Protection Tax as the main body, resource tax, consumption tax, and vehicle purchase tax as the focus, and value-added tax, corporate income tax, farmland occupation tax, and vehicle and vessel tax as supplements [12]. No matter how green taxation is defined, its essence is a policy tool based on the principles of welfare economics: it generates substitution effects (increasing the cost of polluting activities to reduce their occurrence) and income effects (affecting the disposable resources of economic entities) by taxing polluting behavior, while forming incentives through tax incentives, ultimately constraining excessive resource exploitation and ecological environment destruction [13,14] aim to internalize environmental costs and enable the market to effectively allocate resources while considering social costs [15].

Green transformation refers to the process of transforming social, economic, industrial, and energy systems from traditional high pollution, high energy consumption, and high carbon emission models to a development model that has low environmental impact, efficient resource utilization, and ecological sustainability. Its core goal is to ensure economic and social development while reducing damage to natural ecosystems, addressing global challenges such as climate change, resource scarcity, and environmental pollution, and ultimately achieving harmonious coexistence between humans and nature [16]. Green transformation aims to solve the problems of harmonious coexistence between humans and nature, as well as economic, social, and ecological coordination, involving multiple fields such as economy, society, and culture. The ultimate goal is to transform the traditional development model into a scientific development model, achieve sustainable regional development, and promote green economic growth. To achieve this, it is necessary to carry out overall planning, coordinate resources, promote communication and cooperation among different departments, promote technological innovation, improve production methods, and advocate green consumption. Current scholars affirm the necessity of green transformation, believing it can bring significant positive effects to social development. However, direct evaluations of green transformation are relatively scarce. The TEI Unit established the Green City Index (GCI), which includes four dimensions: environmental health, resource conservation, low-carbon development, and livability [17]. Fu et al. combined hybrid models with window analysis to measure the dynamic efficiency of regional industrial green transformation in China from 2006 to 2015 [18]. Yin et al., when evaluating the green transformation of mineral resource-based cities, proposed the MRBC green transformation efficiency evaluation system from the perspectives of input, output, and environmental variables [19]. Cheba et al. used the TOPSIS method to study the green transformation progress of EU countries [20]. Chen Wenjun and Mei Fengqiao employed the SBM directional distance function and GML index to measure the industrial green transformation efficiency of 109 resource-based cities in China [21]. Li et al., based on panel data from 30 Chinese provinces from 2011 to 2020, used the GB-US-SBM model and the global Malmquist–Luenberger (GML) index to study regional differences, dynamic changes, and driving factors of industrial green transformation from static and dynamic perspectives [22]. Meng Xiaoqian and Wu Chuanqing constructed a trinity economic green transformation development index from three aspects: economic green development level, resource and environmental carrying capacity, and green transformation support level. They used methods such as spatiotemporal range entropy weight, Gini coefficient, Theil index, σ convergence, and Markov analysis to evaluate the green transformation development levels of regions at different spatial scales [23].

Taxation is one of the most important means for governments to regulate the macroeconomy and plays a significant role in promoting environmental protection and sustainable development [24]. The “green tax system” is becoming a key index for measuring “green development” and a primary means of restricting activities with negative environmental impacts [25]. Green development can effectively balance economic growth and environmental protection, achieving harmony between humans and nature. General Secretary Xi Jinping emphasized that “green development is the defining feature of high-quality development, and new quality productive forces are inherently green productive forces. We must accelerate the green transformation of development models.”

Currently, domestic and foreign scholars hold two different views on whether green taxation can promote green transformation. The first view is that green taxation can drive green transformation. At the micro level, green taxation increases corporate costs, curbing polluting behavior [26], encouraging green investments [27], and promoting technological innovation to improve energy efficiency [28], thereby facilitating green transformation and upgrading [29]. At the macro level, the imposition of green taxes not only benefits GDP growth but also plays a crucial role in energy conservation and emission reduction, improving environmental quality [30], effectively enhancing green development levels, and achieving sustainable development [31]. The second view is that the impact of green taxation on green transformation is not significant. At the micro level, environmental regulations have a significantly negative impact on corporate performance, hindering sustainable development [32]. At the macro level, China’s environmental taxation primarily relies on incentive-based taxes, while regulatory measures such as consumption tax and resource tax have limited control over polluting products and behaviors, failing to fully realize their environmental governance potential and achieve pollution reduction goals [33]. Some scholars also argue that environmental regulations have a significantly negative effect on regional ecological efficiency. With the increase in Environmental Protection Tax revenue, emissions of air and water pollutants not only fail to decline but may even rise [34].

Existing research has accumulated a certain amount around green taxation, urban green transformation, and their relationship. However, current studies have not addressed the mediating role of urban investment platform debt in the relationship between the two. As an important subject of urban green investment, how to connect green taxation and urban green transformation is still an unexplored field. This article innovatively introduces the intermediary variable of urban investment platform debt, attempting to provide a new analytical dimension for the study of the relationship between green taxation and urban green transformation, and deeply analyze the transmission mechanism of urban investment platform debt in it, so as to comprehensively understand the intrinsic logic of urban green development.

3. Theoretical Mechanism and Research Hypotheses

3.1. The Impact of Green Taxation on Green Transformation

The core proposition worth exploring at present is whether to impose taxes or provide subsidies. Green taxation, as a powerful government regulatory measure in environmental regulation, belongs to a type of taxation that changes behavior by influencing the cash flow of sustainable enterprises or consumers, and has a profound impact on green development.

On the one hand, green taxation can reduce negative behaviors by producers and consumers. For producers, the imposition of green taxes increases economic costs and governance burdens [35]. However, in a well-functioning market environment, competition among enterprises intensifies. Small-scale, inefficient, and highly polluting enterprises will face rising environmental costs, affecting profitability and performance, and may eventually be eliminated from the market. Meanwhile, large-scale, capable enterprises will adopt greener and more efficient production technologies in response to government environmental policies [36], optimizing internal process controls to avoid government penalties and excessive tax burdens, thereby achieving better economic performance and surviving market competition. This “survival of the fittest” scenario promotes the healthy development of the entire market, facilitating green transformation of industrial structures and improving regional ecological environment quality. For consumers, taxes such as consumption tax, vehicle and vessel tax, and vehicle purchase tax establish price- and pollution-intensity-linked adjustment mechanisms, increasing purchase costs and constraining consumer demand for high-pollution, high-emission products. Consumers may turn to less polluting and lower-priced alternatives, changing consumption patterns. Additionally, more consumers are opting for public transportation, rail transit, or even zero-emission shared bicycles. In vehicle purchases, there is a growing preference for relatively lower-priced new energy vehicles.

On the other hand, green taxation helps balance resource allocation. As a continuous policy tool, green taxation increases government fiscal revenue, regulates social income distribution, and encourages the development of specific industries and regions through a guiding role similar to “incentive rewards”, enhancing the balance and sustainability of China’s green economy development. For example, urban land use tax and farmland occupation tax are essentially economic compensation for the occupation of public resources, achieving optimal allocation of social resources by affecting the initial occupation cost. In the context of green development, such taxes can support new development directions such as urban green transformation and large-scale agricultural comprehensive development, addressing externalities in development and injecting new momentum into urban green development.

Moreover, China has a large land area and uneven regional development. There are significant differences in resource endowment, industrial structure, and economic development level among different regions. These regional characteristics will affect the effectiveness of green taxation on urban green transformation. Therefore, the impact of the same green taxation policy on green development in different regions varies greatly.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Green taxation has a significant promoting effect on urban green transformation, and the impact of green taxation on urban green transformation varies significantly in different regions.

3.2. The Mediating Role of Urban Investment Platform Debt in the Relationship Between Green Taxation and Green Transformation

As the core carrier of long-term fixed asset stock (especially green infrastructure) formed through debt financing, the debt scale expansion and structural adjustment of urban investment platforms have always been embedded in the practical logic of local governments promoting urban green transformation. In 2014, the State Council issued the Opinions on Strengthening the Management of Local Government Debt (State Council Document [2014] No.43) [37], explicitly proposing to “standardize local government debt-financing mechanisms and strip financing platform companies of their government financing functions.” This policy direction has promoted the transition of urban investment platform debt from implicit to semi-transparent and standardized management. Urban investment platform debt mainly includes debt formed by local governments through urban investment companies, a special financing entity. In terms of debt types, it can be broadly divided into three categories: bank loans, bond financing, and non-standard financing. Its root cause lies in the contradiction between local economic development needs and fiscal revenue and expenditure. To promote urban infrastructure construction, public service provision, and industrial upgrading, local governments use urban investment platforms as market-oriented vehicles to raise funds, meeting the enormous capital demands of rapid local economic development. In essence, urban investment platform debt is a special financing arrangement by local governments under economic construction and fiscal constraints, a product of the mismatch between capital demand and supply during urbanization. It provides critical funding for local infrastructure construction, playing an irreplaceable role in improving urban transportation networks, enhancing public service levels, and promoting sustainable development, thereby effectively driving local economic growth and urban transformation and upgrading.

The impact of green taxation on the debt of urban investment platforms exhibits significant intertemporal characteristics, which are closely related to the flow attributes of tax policies and the stock characteristics of urban investment products. In the short term, environmental tax burden directly squeezes operational cash flow to drive up debt demand: the tiered collection mechanism of environmental protection tax on pollutant emissions forces urban investment platforms to increase investment in pollution control equipment in projects such as waste incineration power generation and industrial wastewater treatment; After the reform of resource tax, the tax rates on sand, gravel, coal and other materials have been raised, leading to an increase in the cost of traditional infrastructure projects and forcing urban investment to expand its debt scale to alleviate the situation. In the long run, the restructuring of regional development expectations triggered by green tax policies will indirectly affect debt decisions through asset valuation. When green transformation policies improve the asset return rate of eco-friendly regions, urban investment platforms may actively expand their debt scale to accelerate the layout of projects such as photovoltaic industrial parks and circular economy demonstration zones, forming a positive cycle of “policy expectations asset appreciation debt expansion”. This bidirectional influence mechanism confirms that green taxation, as a flow based policy tool, needs to be examined in a cross period framework for its regulatory effect on the scale of urban investment debt.

The debt scale of urban investment platforms affects the process of urban green transformation through the transmission mechanism of asset stock, which is reflected in three levels. From the perspective of government governance, the increase in the stock of green infrastructure invested by debt funds directly enhances the implementation capacity of local government environmental regulations. From the perspective of corporate behavior, the green infrastructure stock led by urban investment has formed a positive externality effect: the use of facilities such as centralized heating systems and recycled water reuse pipelines in industrial parks not only reduces the environmental compliance costs of enterprises, but also forces high energy consuming enterprises to accelerate technological transformation through the “infrastructure lock-in effect”. From the perspective of public participation, the stock expansion of livelihood oriented green assets such as debt driven urban green spaces and new energy public transportation has intuitively improved the quality of residents’ living environment.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2:

The debt scale of urban investment platforms plays an intermediary role in the relationship between green taxation and urban green transformation.

4. Variable Selection and Model Construction

4.1. Variable Selection

4.1.1. Explanatory Variable

Green taxation (Tax). This paper defines green taxation broadly. Considering data availability, the following eight tax revenues are selected for measurement: Environmental Protection Tax (pollution discharge fees), consumption tax, resource tax, urban maintenance and construction tax, vehicle purchase tax, vehicle and vessel tax, farmland occupation tax, and urban land use tax. The composition of green taxation and the purpose of related taxation in this article are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of Green Taxation.

4.1.2. Explained Variable

Green transformation (Green). This paper refers to the Ecological Civilization Construction Assessment Target System and the Green Development Indicator System to construct the green transformation indicator system [38], as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Green Transformation Indicator System.

The measurement of urban green transformation level needs to meet the requirements of multi index integration, objective unbiasedness, cross city comparability, and dynamic adaptation. The entropy method perfectly adapts to these needs through characteristics such as “data-driven objective weighting”, “multi-dimensional information integration”, and “horizontal/vertical comparability”. Therefore, this paper uses the entropy method to measure the green transformation efficiency of 30 provinces (cities and autonomous regions) in China except Xizang from 2011 to 2021.

The specific calculation process is as follows:

First, to eliminate the impact of different units on the calculation results, the data is standardized using the range standardization method, denoted as . The range standardization formula is:

Next, the proportion of the i-th indicator for the j-th province is calculated (where n is the number of provinces):

Then, the information entropy of the indicator is calculated:

Subsequently, the redundancy of information entropy is calculated:

The weight of the indicator is then calculated:

Finally, the green transformation score for each province is calculated:

In the formulas, represents the original value of the i-th indicator for the -th province, represents the standardized value of the i-th indicator for the -th province, represents the proportion of the i-th indicator for the j-th province, represents the information entropy of the i-th indicator, K represents the Boltzmann constant, represents the redundancy of information entropy for the i-th indicator, represents the weight of the i-th indicator, and represents the green transformation score for each province. The specific calculation results are shown in Table A1.

4.1.3. Control Variables

Referring to Chi Qiaozhu and Chen Shaohui [39], Pei Erjie and Zhang Zhidong [40], and others, and combining with this study, the following control variables that may affect green transformation are included:

- (1)

- Urbanization level (Urb). The proportion of urban permanent residents to the total population.

- (2)

- Population quality (Hum). The proportion of regular higher education enrollment to the total population.

- (3)

- Government behavior level (Gov). The proportion of local government general budget expenditure to GDP.

- (4)

- Population density (Pop). Measured as the ratio of urban year-end population to administrative area.

- (5)

- Openness to the outside world (Ope). The proportion of total import and export volume at the location of business units to GDP.

The symbols, meanings, and explanations of each major variable are summarized in Table 3:

Table 3.

Qualitative Description of Main Variables.

4.1.4. Data Description

Based on data availability, this paper selects panel data from 30 provinces (municipalities, autonomous regions) excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan from 2011 to 2021 as the sample. All the original data are from the China Tax Yearbook, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook, statistical yearbooks of various provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities directly under the central government) over the years, and CEIC database, EPS database. For a small number of missing values in the data, interpolation is used for supplementation.

The descriptive statistics of the variables used in this paper are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics of Main Variables.

4.1.5. Correlation Test

If two or more variables exhibit universal correlation, i.e., multicollinearity, it will be difficult to analyze the individual influence of each variable on the explained variable, affecting the authenticity of the model estimation results and leading to model distortion or inaccurate regression results. Therefore, this paper uses the variance inflation factor (VIF) to test whether the selected data exhibit multicollinearity. The specific test results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Variance Inflation Factor.

Table 4 shows the variance inflation factors, indicating that the selected data do not exhibit multicollinearity.

4.2. Model Construction

This paper selects panel data from 30 provinces (municipalities, autonomous regions) excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan from 2011 to 2021 to estimate the impact of green taxation on green transformation. The basic econometric model is as follows:

Here, Greeni,t represents the dependent variable in this study, denoting the green transformation status of province i in year t; Taxi,t represents the independent variable, indicating the green tax revenue of province i in year t; the remaining variables are control variables, including urbanization level (Urb), population quality (Hum), government intervention level (Gov), population density (Pop), and openness to external trade (Ope). and denote individual fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively, while represents the error term.

5. Analysis of Empirical Results

5.1. Baseline Regression Results

All data analyses in this study were conducted using STATA 17.0 software.

This study conducted a Hausman test and chose to use a fixed-effects model. At the same time, in order to better observe the impact of green taxation on green transformation, this article conducted a stepwise regression analysis.

This article gradually added control variables to Equation (1) for regression, and the results are shown in Table 6. After adding all control variables to column (6), the green tax coefficient is positive, and the effect of green transformation increases with the increase in green tax, indicating that green tax has a significant positive effect on green transformation. Green taxation has a significantly positive effect on green transformation. The regression coefficient for green taxation is 0.730 and is significant at the 1% level, meaning that increasing green taxation levels can effectively promote green transformation to a certain extent. This result supports Hypothesis 1. On the one hand, green taxation directly increases the production costs of polluters, reducing profit margins and diminishing corporate competitiveness. Driven by profit maximization, enterprises will make changes across extraction, production, and distribution processes to lower costs—reducing the use of traditional raw materials, adopting renewable energy for low-tax green products, utilizing energy-saving and environmentally friendly machinery, minimizing pollution emissions during distribution, and innovating technologies to improve efficiency and reduce pollution. Enterprises that fail to innovate or transition to greener practices may face declining competitiveness due to higher tax burdens, potentially leading to shutdowns or market exits, which benefits the screening of efficient production capacity and environmental protection. On the other hand, imposing green taxes on highly polluting products raises their prices, guiding consumers to adjust their purchasing behavior toward environmentally friendly products and prioritize green lifestyles, indirectly promoting green transformation.

Table 6.

Impact of Green Taxation on Green Transformation.

5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

This study divides the sample into eastern and central-western regions to explore the heterogeneous impact of green taxation on green transformation across different geographical areas. The regression results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Heterogeneous Impact of Green Taxation on Green Transformation.

Table 7 shows that the impact of green taxation on green transformation varies across regions. In the eastern region, the coefficient for green taxation is 1.348 and significant at the 1% level. In the central-western region, the coefficient is 0.238 and also significant at the 1% level. This result indicates that the collection of green taxes can promote urban green transformation in both the eastern and central western regions. However, in terms of its impact, the collection of green taxes in the eastern region has a much higher impact on green transformation than in the central and western regions. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is differences in industrial structure. Most central-western cities in China are resource-based, with secondary industries dominating their economies. The development of modern services and high-tech industries is relatively slow, making it difficult for industrial structures to shift rapidly in response to green taxation. Additionally, compared to the central-western regions, eastern governments may implement green taxation policies more proactively to drive economic transformation and sustainable development, attracting more investment and corporate participation, thereby enhancing the efficiency of green transformation.

5.3. Robustness Tests

To verify the robustness of the baseline model’s estimation results regarding the impact of green taxation, this study employs two methods: shortening the sample period and adding instrumental variables.

5.3.1. Shorten the Time Sample

Considering the impact of the pandemic since 2020, this study removes data from 2020 onward and retests the regression results. The results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Robustness Test: shortened time samples.

The regression results confirm that the positive impact of green taxation on green transformation remains significant, supporting the robustness of the findings.

5.3.2. Changing the Regression Method

This study employs the generalized least squares method to retest the regression results. The results are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Robustness Test: Generalized Least Squares Regression.

The regression results confirm that the positive impact of green taxation on green transformation remains significant, further supporting the robustness of the findings.

5.4. Endogeneity Test

This study uses the system GMM model for endogeneity testing. Table 10 shows the results of the endogeneity test.

Table 10.

Endogeneity Test.

The estimation results of the GMM model show that green taxation has a significant positive impact on urban green transformation, with a coefficient that is significant at the 1% statistical level. This significance remains stable during the gradual optimization of instrumental variables, indicating that green taxation has a positive promoting effect on urban green transformation. In addition, the p-value of AR (2) in the Arellano Bond test is 0.731, which satisfies the core hypothesis of the dynamic panel model that there is no second-order autocorrelation in residuals, indicating the rationality of the model setting; The p-value of Hansen’s over identification test is 0.218, which does not reject the null hypothesis of exogenous instrumental variables, further verifying the effectiveness of instrumental variable selection. Therefore, it can be inferred that green taxation has a significant positive impact on urban green transformation.

6. The Mediating Effect of Urban Investment Platform Debt

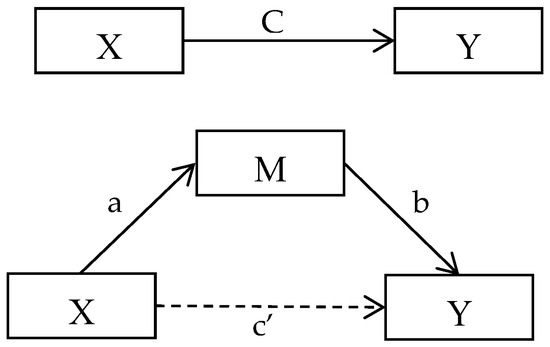

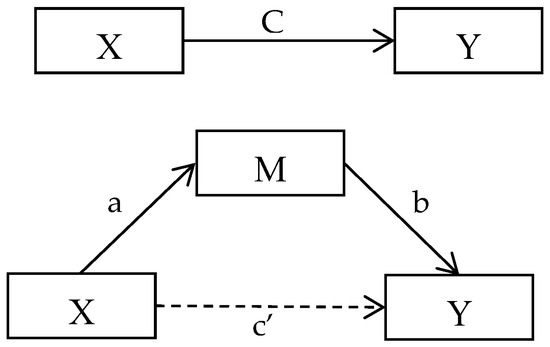

The principle of studying mediating effects lies in explaining that, in addition to directly affecting the dependent variable Y, the independent variable X can also influence Y through an intermediate variable M, where M is the mediating variable. As shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Path of Mediating Effect.

Y = cX + e1

M = aX + e2

Y = aX + bM + e3

To test Hypothesis 2 and explore the pathway through which green taxation affects green transformation, this study examines the mediating role of urban investment platform debt based on the above influence path. The specific model is constructed as follows:

Here, Debt represents the mediating variable, urban investment platform debt; Controls represents a series of control variables, including urbanization level (Urb), population quality (Hum), government behavior level (Gov), population density (Pop), and openness to the outside world (Ope); and represent individual and time effects, respectively; and represents the error term.

To measure the scale of urban investment platform debt, this study uses the ratio of interest-bearing debt of urban investment platforms to GDP.

The regression results are shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Mediating Effect of Urban Investment Platform Debt.

The regression results in Column (2) of Table 10 show that the coefficient for the impact of green taxation on urban investment platform debt is 0.739 and significant at the 5% level, indicating that green taxation may increases the scale of urban investment platform debt. Column (3) shows that after adding the mediating variable (urban investment platform debt), the coefficient for the impact of green taxation on green transformation is 0.648 and significant at the 1% level. This suggests that green taxation can enhance the pace of green transformation. However, compared to the model without the mediating variable, the coefficient for green taxation decreases significantly after including the mediating variable, indicating that urban investment platform debt plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between green taxation and green transformation. This validates Hypothesis 2.

7. Research Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

7.1. Research Conclusions

This study is based on the theoretical framework of “green taxation—urban investment platform debt—urban green transformation”, and systematically analyzes the impact mechanism and heterogeneity of green taxation on urban green transformation from both theoretical and empirical perspectives. Based on the existing research, this study constructed an indicator system of urban green transformation, measured the urban green transformation level of 30 provinces in China using the entropy method, then used provincial panel data from 2011 to 2021 to study the impact of green tax on urban green transformation through the two-way fixed-effects model, and finally used the intermediary model to explore the intermediary role of the debt scale of urban investment platform in the impact of green tax on urban green transformation. The findings are as follows: Green taxation has a positive and significant effect on promoting urban green transformation, and the impact of green taxation on green transformation has regional heterogeneity. Due to differences in regional industrial structure and local government policy implementation, the impact of green taxation on green transformation has regional heterogeneity. The impact of green taxation on urban green transformation in eastern China is significantly higher than that in central and western regions. In addition, mechanism testing shows that the debt scale of urban investment platforms plays a partial mediating role between green taxation and green transformation.

7.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the above conclusions, this study proposes the following policy recommendations:

First, the positive role of green taxation should be leveraged by rationally expanding its scope. Specifically, the coverage of the Environmental Protection Tax should be broadened to include waste classification and carbon emissions, aligning with policies such as “carbon peak” through tax incentives. Additionally, the regulatory function of consumption taxes should be fully utilized by incorporating more highly polluting and resource-intensive consumer goods, such as plastic bags, into the tax base. Furthermore, the guiding role of vehicle and vessel taxes and vehicle purchase taxes in promoting green consumption and reducing energy consumption should be emphasized. Tax standards should be refined and updated based on principles that encourage low energy consumption, such as incorporating fuel consumption metrics.

Second, regional development disparities should be addressed to promote green transformation tailored to local conditions. In eastern regions, targeted tax incentives, such as tax reductions and subsidies, can be implemented to guide enterprises in phasing out outdated production capacities, adopting advanced environmental technologies, and achieving green industrial upgrading. In central and western regions, local resource advantages should be leveraged to develop clean energy and circular economy industries. Tax exemptions or reductions for enterprises engaged in comprehensive resource utilization can enhance resource recycling and reduce environmental pollution. Moreover, cross-regional green industry collaborations between eastern and central-western regions should be encouraged through tax policies. For instance, preferential tax treatments for interregional green projects can facilitate the dissemination of green technologies and best practices, fostering resource sharing and complementary advantages.

Third, the debt scale of urban investment platforms should be appropriately adjusted to sustain their mediating role. On one hand, governments should closely monitor local fiscal conditions and the dynamics of green industry development, establishing scientifically sound debt scale control targets and phased plans. While increasing fiscal funding for green projects, efforts should be made to diversify financing channels and innovate financing models to ensure efficient and orderly investment in green initiatives. On the other hand, urban investment platforms should prioritize directing debt capital toward emerging green sectors, supporting the transition of traditional industries toward low-carbon models. Debt financing should accelerate the construction of smart city environmental monitoring systems, green transportation networks, and other digital and intelligent infrastructure, thereby enhancing the intelligence level and operational efficiency of urban green development.

7.3. Shortcomings and Next Research Plan

The shortcomings of this article lie in three aspects: firstly, due to the limitation of data availability, this article can only analyze the impact of green taxation on urban green transformation based on provincial data. Compared with prefecture level data, provincial data struggles to fully demonstrate the regional characteristics of research results, making it difficult to accurately reflect the unique situations of different regions; secondly, this article has certain limitations in the construction of urban green transformation indicators, and due to the availability of data, interpolation is used to fill in some missing data, resulting in certain deviations in the calculation results. This needs to be further improved in future research, considering the measurement of green development efficiency from multiple perspectives and improving the accuracy of the data. Thirdly, the synergy mechanism between the fiscal funds generated by green taxation and the debt of urban investment platforms in green projects needs further clarification.

Based on the shortcomings of this article, the next research plan will focus on the following aspects to deepen and improve the research: firstly, to break through the limitations of data acquisition. Actively establish cooperative relationships with local statistical departments, environmental protection agencies, and other relevant units, striving to obtain more detailed data at the prefecture level. Through field research, data sharing, and other methods, make up for the shortcomings of existing provincial-level data in displaying regional characteristics, so as to more accurately analyze the differentiated impact of green taxation on urban green transformation under different city sizes, resource endowments, and industrial structures, and reveal the underlying mechanisms behind regional heterogeneity. Secondly, optimize the indicator system and data-processing methods for urban green transformation. Construct a more scientific and systematic evaluation indicator system from multiple dimensions including environmental pollutant emissions, energy consumption, ecosystem service value, green innovation capability, and residents’ green living standards. Meanwhile, improve data-processing methods by adopting more rigorous missing-value handling techniques to reduce data deviation and enhance the reliability of calculation results. Thirdly, focus on exploring the conversion mechanism of green tax revenue into green investment on urban investment platforms. By constructing a dynamic model that includes the risk premium of urban investment debt and expected project returns, this study quantitatively analyzes the substitution effect between fiscal subsidies, special debt quotas, and market-oriented financing of urban investment formed by green taxation. It reveals the optimal path for fund conversion under different policy tool combinations, providing theoretical support for improving the efficiency of green fund allocation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X. and H.Z.; methodology, H.Z. and Y.G.; software, H.X.; formal analysis, H.X.; writing—original draft preparation, H.X.; Writing—review and editing, H.X. and Y.G. visualization, H.Z.; validation, Y.G. and S.H.; investigation, S.H. and E.Z.; resources, H.X.; data curation, H.X. and H.Z. and E.Z.; project administration, H.X. and Y.G.; supervision, Y.G.; funding acquisition, H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by General Project for Philosophy and Social Science Research in Jiangsu Universities (Project name: Research on the Impact of Discipline Construction on Industrial Structure Optimization from the Perspective of New Quality Productivity, Approval Number: 2025SJYB0204), and the Nanjing University of Finance and Economics School level Education Reform Project (Project name: Research on the Quality Evaluation Index System for Doctoral Student Training, Approval number: XYJS3202403).

Data Availability Statement

This paper selects 30 provinces in China (omitting Xizang, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan), and the time span is 2011–2021. All the original data are from the China Tax Yearbook, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook, statistical yearbooks of various provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities directly under the central government) over the years, and CEIC database, EPS database. For a small number of missing values in the data, interpolation is used for supplementation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Green Transformation Measurement Results.

Table A1.

Green Transformation Measurement Results.

| Province | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Tianjin | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| Hebei | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Shanxi | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Neimenggu | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| Liaoning | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| Jilin | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.115 | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Shanghai | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.71 |

| Jiangsu | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.43 |

| Zhejiang | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.47 |

| Anhui | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| Fujian | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Jiangxi | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.18 |

| Shandong | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| Henan | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Hubei | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| Hunan | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Guangdong | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.43 |

| Guangxi | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| Hainan | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Chongqing | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.23 |

| Sichuan | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Guizhou | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Yunnan | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Shaanxi | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| Gansu | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Qinghai | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Ningxia | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Xinjiang | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

References

- The Report to the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. Available online: https://msxy.sdut.edu.cn/2012/1119/c4495a194354/page.htm (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Communique of the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2015-10/29/c_1116983078.htm (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- The Report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-10/25/content_5721685.htm (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Xi Jinping’s Speech at the 11th Collective Study of the 20th—Central Political Bureau. Available online: http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2024-05/31/c_1130154174.htm (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council Issued the “Opinions on Accelerating the Comprehensive Green Transformation of Economic and Social Development”. Available online: https://zgjssw.jschina.com.cn/zhiduhuibian/202408/t20240815_8377753.shtml (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Government Work Report. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202503/content_7013163.htm?s_channel=5&s_trans=7824452999_ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Pigou, A.C. The Economics of Welfare; Macmillan and, Co.: London, UK, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, L.X. Research on the connotation of green taxation. Price Mon. 2003, 9, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A.Z. Construction of China’s “green” tax system. Tax. Res. 2006, 7, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.L.; Wang, Y.J. Research on the greening degree of China’s tax system: Measurement based on three statistical caliber indicators. Audit Econ. Res. 2013, 28, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.C.; Zhao, D. Construction of a green tax system based on environmental protection tax. Tax. Res. 2020, 11, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.P.; Chen, B. “Carbon peak and carbon neutrality” goals and the construction of a green tax system. Tax Econ. Res. 2022, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, S.C.; Hosan, S.; Chapman, A.J.; Saha, B.B. The role of environmental taxes on technological innovation. Energy 2021, 232, 121052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štreimikienė, D.; Samusevych, Y.; Bilan, Y.; Vysochyna, A.; Sergi, B.S. Multiplexing efficiency of environmental taxes in ensuring environmental, energy, and economic security. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 7917–7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwilinski, A.; Ruzhytskyi, I.; Patlachuk, V.; Patlachuk, O.; Kaminska, B. Environmental taxes as a condition of business responsibility in the conditions of sustainable development. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2019, 22, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.D. Handbook of Research on Sustainable Development and Economics; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- TEI Unit. Asian Green City Index: Assessing the Environmental Performance of Asia’s Major Cities; Siemens AG: Munich, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Xiao, G.; Guo, L.; Wu, C. Measuring the dynamic efficiency of regional industrial green transformation in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wan, K.; Wang, D. Evaluation of green transformation efficiency in Chinese mineral resource-based cities based on a three-stage DEA method. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheba, K.; Bąk, I.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Ioppolo, G. Directions of green transformation of the European Union countries. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.J.; Mei, F.Q. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors of industrial green transformation efficiency in resource-based cities. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 38, 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wu, L. The dynamic evolution of China’s industrial green transformation from 2011–2020: A comprehensive study based on intertemporal transition. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2023, 16, 1561–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.Q.; Wu, C.Q. Discussion and application of evaluation methods for economic green transformation development index. Reg. Econ. Rev. 2023, 1, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, M.; Bozatli, O. The effects of green innovation, environmental taxes, and financial development on renewable energy consumption in OECD countries. Energy 2023, 280, 128105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabău-Popa, C.D.; Bele, A.M.; Negrea, A.; Coita, D.C.; Giurgiu, A. Do energy consumption and CO2 emissions significantly influence green tax levels in European countries? Energies 2024, 17, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Chen, Z.; Shen, Z.; Shabbir, M.S.; Bokhari, A.; Han, N.; Klemeš, J.J. The effect of cleaner and sustainable sewage fee-to-tax on business innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Qiu, B.; Chan, K.C.; Zhang, H. Does a green tax impact a heavy-polluting firm’s green investments? Appl. Econ. 2022, 54, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Sheikh, A.A.; Hamid, Z.; Senkus, P.; Borda, R.C.; Wysokińska-Senkus, A.; Glabiszewski, W. Exploring the causal relationship among green taxes, energy intensity, and energy consumption in Nordic countries: Dumitrescu and Hurlin causality approach. Energies 2022, 15, 5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Z. Green taxation promotes the intelligent transformation of Chinese manufacturing enterprises: Tax leverage theory. Sustainability 2022, 13, 13321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenberg, A.L. Environmental taxes and the double dividend. Empirica 1998, 25, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, M.; Ramos-Meza, C.S.; Jain, V.; Salman, A.; Kamal, M.; Shabbir, M.S.; Rehman, M.U. The dynamic relationship between green tax incentives and environmental protection. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2023, 30, 32184–32192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackman, A.; Kildegard, A. Clean technological change in developing-country industrial clusters: Mexican leather tanning. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2010, 12, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Ming, H.R.; Liu, Y.L. The “inverted U” effect of environmental protection tax on pollution reduction: Based on regional collection intensity measurement. Tax Econ. Res. 2020, 25, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.J.; Liu, Y.S. Empirical study on the pollution reduction effects of environmental taxes and fees in China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2015, 25, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.J.; Zhang, X. Research on the relationship and evaluation between green taxation and economic development. Times Financ. 2020, 16, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Y.; Ma, X.J.; Yang, J. The dual impact effects of green taxation on green innovation efficiency of industrial enterprises. Financ. Dev. Res. 2020, 12, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Opinions on Strengthening the Management of Local Government Debt (Guofa [2014] No. 43). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-10/02/content_9111.htm (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- The National Development and Reform Commission Issued the Green Development Index System and the Assessment Target System for Ecological Civilization Construction. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-12/23/content_5151575.htm (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Chi, Q.Z.; Chen, S.H. Research on the impact of green taxation on total factor carbon productivity under the “dual carbon” goals. Environ. Prot. 2023, 51, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, E.J.; Zhang, Z.D. The impact of digital infrastructure construction on high-quality economic development: A quasi-natural experiment based on the “Broadband China” strategy. East China Econ. Manag. 2024, 38, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).