Platformization in Tourism: Typology of Business Models, Evolution of Market Concentration and European Regulation Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How has market concentration evolved in the tourism industry under the influence of platformization?

- What are the key indicators of platformization in tourism, and how do they reflect the sector’s transformation?

- What are the major regulatory responses, particularly in the EU, to address challenges posed by platformization?

2. Methods

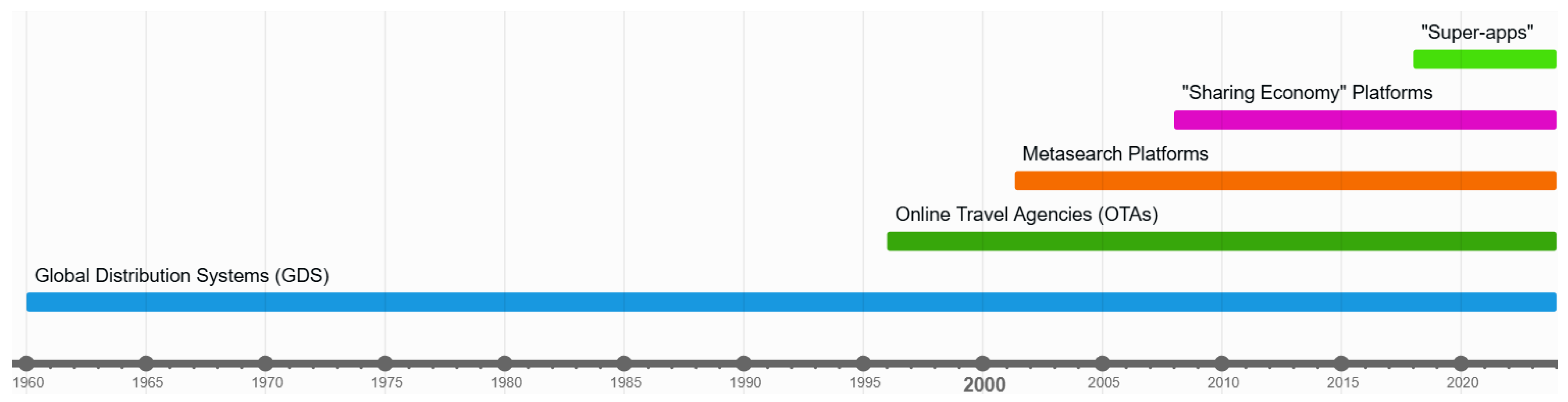

3. Historical Evolution of Tourism Distribution Platforms

3.1. Since 1960s: Global Distribution Systems (GDS) as the First Travel Platforms

3.2. Since the 1990s, Online Travel Agencies and the Rise of the Travel Duopoly: Booking vs. Expedia

3.3. Since the 2000s, Using the Free User Labor and Selling Online Analytics: Tripadvisor

3.4. Since the 2010s, Challenging the Travel Duopoly from Bellow: Airbnb and the “Sharing Economy”

3.5. Since the 2020s, Challenging the Travel Duopoly from Above: The “Scary 5” and the “Super-Apps”

4. Indicators of Platformization in Tourism

- Increase efforts to regulate the economic activities of the platform economy through legislation to limit the negative impacts on businesses and employment in the hospitality and tourism sector;

- Collect coherent data;

- Create measured deterrents for operators not respecting requirements by legislation through appropriate sanctions;

- Guarantee that legislation is fully respected by all providers of hospitality and tourism services, through effective enforcement, supported by resources and legal powers for public authorities to do their jobs correctly, so that customers are protected, employees are treated fairly and entitled to their rights, and responsible businesses enjoy a fair competitive environment/level playing field [26] (p. 2).

4.1. Platformization of Tourism Distribution

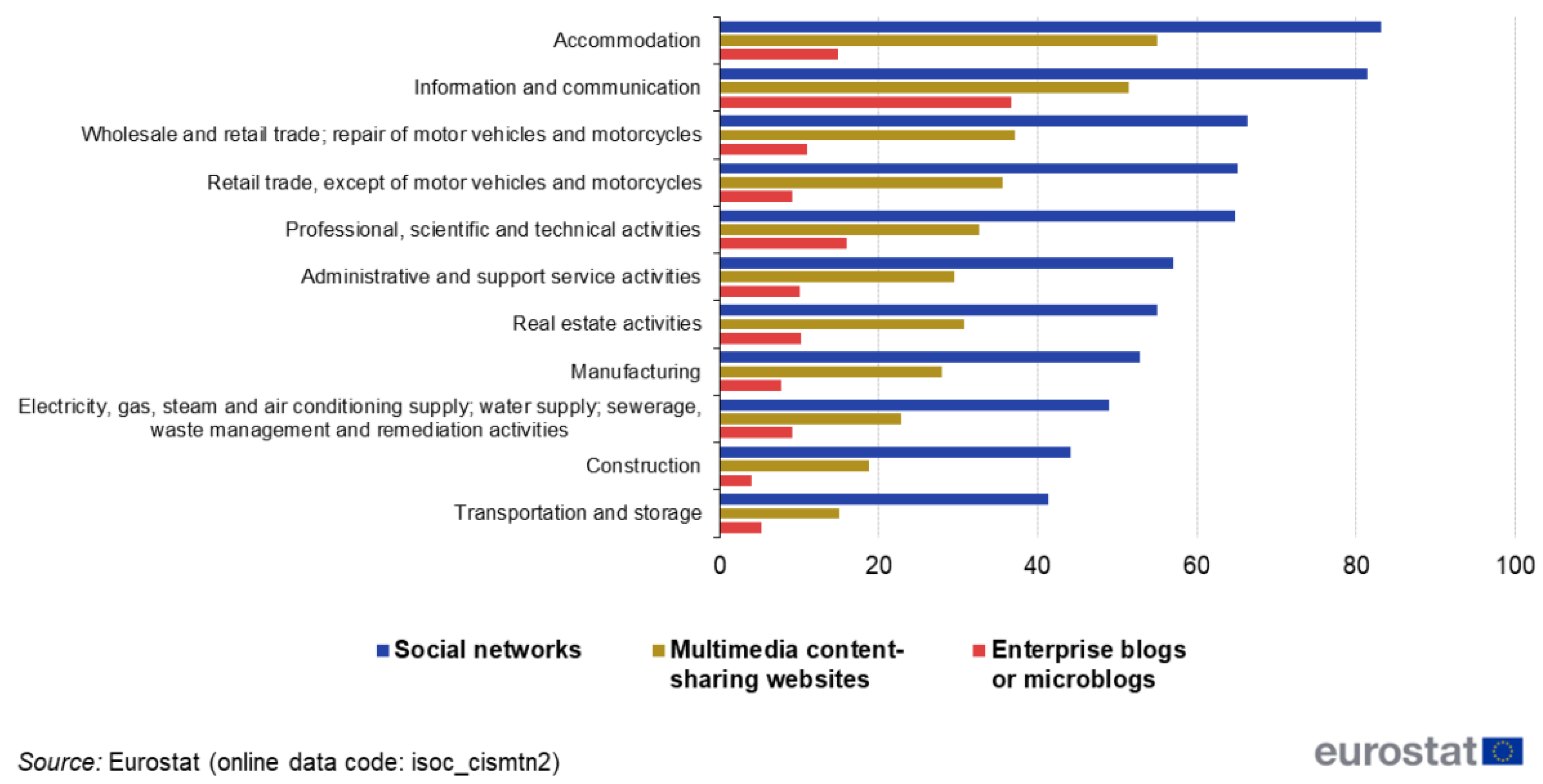

4.2. Platformization of Tourism Promotion

4.3. Platformization of Human Resources Management (HRM) in Tourism

5. Addressing Market Concentration: The Need for a Robust Competition Policy in the Tourism Industry

5.1. Price Parity Clauses: A Mechanism for Market Control in the European Tourism Industry

5.2. Ensuring Fair Competition in the Digital Economy and OTA Markets: The Role of the Digital Markets Act

5.3. Booking.com’s Market Power Under Scrutiny: Recent Regulatory Actions in Spain and Italy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reinhold, S.; Zach, F.J.; Laesser, C. E-business models in tourism. In Handbook of e-Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vinod, B. Mastering the Travel Intermediaries: Origins and Future of Global Distribution Systems, Travel Management Companies, and Online Travel Agencies; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, D.G.; McKenney, J.L. Airline reservations systems: Lessons from history. MIS Q. 1988, 12, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.R.; Lee, Y.-H.A. The economics of regulatory reform: Termination of airline computer reservation system rules. Yale J. Reg. 2004, 21, 369. [Google Scholar]

- Ravich, T.M. Deregulation of the Airline Computer Reservation Systems (CRS) Industry. J. Air L. Com. 2004, 69, 387. [Google Scholar]

- Cure, M.; Hunold, M.; Kesler, R.; Laitenberger, U.; Larrieu, T. Vertical integration of platforms and product prominence. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2022, 20, 353–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Experimental Statistics, Collaborative Economy Platforms. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/experimental-statistics/collaborative-economy-platforms (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Dredge, D.; Gyimóthy, S. Collaborative economy and tourism. In Collaborative Economy and Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Oskam, J.; Boswijk, A. Airbnb: The future of networked hospitality businesses. J. Tour. Futures 2016, 2, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahokoupil, J.; Fabo, B. The platform economy and the disruption of the employment relationship. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cansoy, M.; Schor, J. Who Gets to Share in the “Sharing Economy”? Racial Discrimination in Participation, Pricing and Ratings on Airbnb; Boston College: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sans, A.A.; Quaglieri, A. Unravelling Airbnb: Urban perspectives from Barcelona. In Reinventing the Local in Tourism: Producing, Consuming and Negotiating Place; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2016; Volume 73, p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Aurioles, B.; Tussyadiah, I. What Airbnb does to the housing market. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 90, 103108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbler, B.; Obrč, P. The impact of Airbnb on long-term rental housing: The case of Ljubljana. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2021, 8, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Turnšek, M.; Ladkin, A. The Algorithmic Management: Reflecting on the Practices of Airbnb. In Human Relations Management in Tourism; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Turnšek, M.; Ladkin, A. Algorithmic Management. In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing; Buhalis, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- Turnšek, M.; Ladkin, A. Nova pravila igre za delavce? Airbnb in platformna ekonomija. Javnost-The Public 2017, 24, S82–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegro, T.; Turnšek, M.; Špindler, T.; Petek, V. Introducing Amazon Explore: A digital giant’s exploration of the virtual tourism experiences. J. Tour. Futures, 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Chen, C.-C.; Schwartz, Z. Do I book at exactly the right time? Airfare forecast accuracy across three price-prediction platforms. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2019, 18, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Hopper: Success of a Travel App Startup; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oskam, J.; Zandberg, T. Who will sell your rooms? Hotel distribution scenarios. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airbnb. Airbnb Group, Inc. Annual Report 2023. Available online: https://www.annualreports.com/HostedData/AnnualReports/PDF/NASDAQ_ABNB_2023.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Monica, B.; Giulia, M. “Tourist platformisation”: New Urban Tourism in Milan. In The Power of New Urban Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, D.; Carmo, R.M.; Vale, M. Is the COVID-19 pandemic accelerating the platformisation of the urban economy? Area 2022, 54, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoia, P.; Jokela, S. Platform-mediated tourism: Social justice and urban governance before and during COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFFAT. For a Level Playing Field and Fair Competition in Hospitality and Tourism: Joint EFFAT-HOTREC Statement on the Platform Economy, November 2019. European Federation of Food, Agriculture and Tourism Trade Unions (EFFAT) and Hotels, Restaurants & Cafés in Europe (HOTREC). 2019. Available online: https://effat.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/5A-Joint-HOTREC-EFFAT-Statement-on-Platform-Economy-2019-11-29.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Schegg, R. European Hotel Distribution Study 2024. Results for the Reference Year 2023; Institute of Tourism, University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Western Switzerland & HOTREC: Sierre, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.hotrec.eu/media/static/files/import/all_news_2024_2024_21/hotrec-distribution-study-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Eurostat. Nights Spent at Tourist Accommodation Establishments by Country of Origin of the Tourist. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tour_occ_ninraw/default/table?lang=en&category=tour.tour_inda.tour_occ.tour_occ_n (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Eurostat. Social Media—Statistics on the Use by Enterprises. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Social_media_-_statistics_on_the_use_by_enterprises&oldid=637276 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Eurostat. Employment Statistics—Digital Platform Workers. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Employment_statistics_-_digital_platform_workers (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Ritter, C.S. Travelling with Platform Metrics. In Locating the Influencer: Place and Platform in Global Tourism; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cherif, R.; Hasanov, F. Competition, innovation, and inclusive growth. IMF Work. Pap. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Fact Sheets on the European Union: Competition Policy—European Commission [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/erpl-app-public/factsheets/pdf/en/FTU_2.6.12.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Brühl, V. Big Tech, the Platform Economy and the European Digital Markets. Intereconomics 2023, 58, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Relative Market Share of Major Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) in the Hotel Industry in Europe in 2023—STATISTA [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/870046/online-travel-agency-ota-market-share-in-europe/ (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Krstić, B.; Radivojević, V.; Stanišić, T. Measuring and analysis of competition intensity in the sugar market in Serbia. Econ. Agricul. 2016, 63, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstić, B.; Radivojević, V.; Stanišić, T. Measuring market concentration in mobile telecommunications market in Serbia. Facta Univ. Ser. Econ. Organ. 2016, 13, 247–260. Available online: https://casopisi.junis.ni.ac.rs/index.php/FUEconOrg/article/view/1916/1372 (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Kokkoris, I. Expedia and Booking.com: Agent or Distributor? Competition Policy International 2012. Available online: https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/assets/Uploads/Europe1-24-2013-final.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- UK Competition and Markets Authority. Hotel Online Booking Investigation: Case Closure Summary [Internet]. 2015. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/55f8404aed915d14f1000014/Hotel_online_booking_-_case_closure_summary.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Bundeskartellamt. Case Summary: ‘Best Price’ Clause of Online Hotel Portal Booking Also Violates Competition Law. 2015. Available online: https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Entscheidung/EN/Fallberichte/Kartellverbot/2016/B9-121-13.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Autorité de la Concurrence. Press Release: 21 April 2015: Online Hotel Booking Sector. 2015. Available online: https://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr/en/communiques-de-presse/21-april-2015-online-hotel-booking-sector (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Autorità Garante Della Concorrenza e Del Mercato. Press Release: I779—Commitments Offered by Booking.com: Closed the Investigation in Italy, France and Sweden. 2015. Available online: https://en.agcm.it/en/media/detail?id=42f88c3c-d668-409f-b604-40581a05c97b (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Konkurrensverket. Decision 15/04/2015 Ref. no. 596/2013. 2015. Available online: https://www.konkurrensverket.se/globalassets/dokument/engelska-dokument/beslut/13_0596e.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- European Competition Network. Report on the Monitoring Exercise Carried Out in the Online Hotel Booking Sector by EU Competition Authorities in 2016—European Competition Network [Internet]. 2016. Available online: https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-07/hotel_monitoring_report_en.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- European Commission. Market Study on the Distribution of Hotel Accommodation in the EU—European Commission [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/document/download/1551a94d-e3c0-4175-bdff-d54aef2f6606_en (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- European Commission. About the Digital Markets Act—European Commission [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/about-dma_en (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Bostoen, F. Understanding the Digital Markets Act. Antit. Bull. 2023, 68, 263–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Belloso, N.; Petit, N. The EU Digital Markets Act (DMA): A Competition Hand in a Regulatory Glove. Eur. Law Rev. 2023, 48, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, V.H.S.E. The complementary nature of the Digital Markets Act and the EU antitrust rules. J. Antit. Enfor. 2024, 12, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrescu, D. Designing (restorative) remedies for abuses of dominance by online platforms. J. Antit. Enfor. 2024, jnae040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia. Press Release: The CNMC Fines Booking.com €413.24 Million for Abusing Its Dominant Position During the Last 5 Years [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.cnmc.es/sites/default/files/editor_contenidos/Notas%20de%20prensa/2024/20240730_NP_%20Sancionador_Booking.com_eng.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Autorità Garante Della Concorrenza E Del Mercato. Press Release: A558—Italian Competition Authority: Investigation Opened for Alleged Abuse of Dominant Position by Booking. 2024. Available online: https://en.agcm.it/en/media/press-releases/2024/3/A558 (accessed on 6 October 2024).

| Market Share 2023 | Market Share 2021 | Market Share 2019 | Market Share 2018 | Market Share 2017 | Market Share 2015 | Market Share 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online Distribution Channels = Platforms | (n = 2394) | (n = 3124) | (n = 3044) | (n = 2166) | (n = 2593) | (n = 2188) | (n = 2221) |

| Online Booking Agency (OTA) | 29.1 | 27.1 | 27.1 | 27.3 | 26.9 | 22.3 | 19.3 |

| Global Distribution Systems (GDSs) | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 2.0 |

| Social Media Channels | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turnšek, M.; Radivojević, V. Platformization in Tourism: Typology of Business Models, Evolution of Market Concentration and European Regulation Responses. Platforms 2025, 3, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/platforms3010001

Turnšek M, Radivojević V. Platformization in Tourism: Typology of Business Models, Evolution of Market Concentration and European Regulation Responses. Platforms. 2025; 3(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/platforms3010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurnšek, Maja, and Vladimir Radivojević. 2025. "Platformization in Tourism: Typology of Business Models, Evolution of Market Concentration and European Regulation Responses" Platforms 3, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/platforms3010001

APA StyleTurnšek, M., & Radivojević, V. (2025). Platformization in Tourism: Typology of Business Models, Evolution of Market Concentration and European Regulation Responses. Platforms, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/platforms3010001