1. Introduction

Pastures are the predominant source of forage for grazing animals worldwide, and the sustainability of these agroecosystems is a global priority [

1]. A critical need in many global grazing systems is to improve resilience by increasing the diversity of forage species [

2]. However, in countries like Brazil—where pasture area expanded by 51% over a 32-year period (1985 to 2017) [

3]—approximately 85% of the cultivated pasturelands are composed solely of grasses from the

Urochloa genus [

4], with the Marandu cultivar being the most significant monoculture, covering more than 50 million hectares in 2014 [

5].

In 2022, livestock farming in Brazil relied on 161 million hectares of pasture, accounting for about 19% of the national territory [

6]. Grasses from

Urochloa spp. (syn.

Brachiaria spp.) are the most preferred in cultivated pastures in Brazil and are widely distributed throughout the tropical zone [

4]. Cultivars of

Megathyrsus maximus (syn.

Panicum maximum) are also traditionally important, as they contribute to the intensification of livestock production due to their high diversity and adaptability to various environments [

7]. In addition to their role in animal feed,

Urochloa spp. and

M. maximus grasses are key to the Brazilian tropical forage seed industry, which reached US

$67.1 million in exports in 2022, supplying all Latin American countries [

5,

8].

In the Amazon biome, pastures are commonly established in poorly drained and/or waterlogged soils, exposed to high rainfall rates that can exceed 500 mm/month during the rainy season [

9]. This condition is the primary predisposing factor for the Marandu Death Syndrome (MDS), a complex, multifactorial disease [

10,

11,

12]. MDS is characterized by the interaction between the physiological stress caused by soil waterlogging and the subsequent proliferation and action of soil-borne pathogens [

10,

11]. It is important to note that while controlled experiments often isolate the waterlogging component to study plant tolerance mechanisms, these conditions are not a perfect analogue of the full field MDS, which involves pathogen interaction. This syndrome leads to severe pasture degradation and significant losses in meat and milk production.

MDS has been reported in several tropical regions of the Americas, including Costa Rica [

13], Brazilian Amazon states [

14], and pastures in Colombia, Venezuela, and Guyana [

15]. This has led the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa) and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) to invest in research to identify causes and develop solutions to this issue [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

The study of the response mechanisms inherent to the natural variation in flooding tolerance in plants is an important step for managing waterlogged pastures. Based on this, several studies have been conducted on genotypes from the

Urochloa genus [

17,

18,

19,

20] and

M. maximus [

8,

21,

22]. These studies primarily target morphological, physiological, and anatomical changes, which are relevant because such information supports the selection of genotypes tolerant to poorly drained soils.

In the

Urochloa and

Megathyrsus genera, some cultivars are recommended for pastures under waterlogged conditions.

Urochloa humidicola (syn.

Brachiaria humidicola) is among the most tolerant forage species [

16,

19], playing an important role in systems affected by MDS. In

M. maximus, cultivars such as ‘Mombaça’ and ‘BRS Zuri’ have been recommended to increase the persistence of pastures in poorly drained soils [

9,

21,

23]. These recommendations are often based on field observations of persistence under poorly drained conditions. Although the recommendation of cultivars for use in waterlogged and/or flooded soils has increased, identifying genotypes that combine excellent flooding tolerance with high biomass production and nutritional quality is still necessary [

20]. To accelerate the breeding process, effective selection requires a controlled-environment screening method using simple methodology, based on the evaluation of easily measurable traits. While physiological traits are difficult to assess, they are important for identifying tolerance to this stress [

18,

24,

25]. Currently, employed methods generally assess a small number of genotypes and focus on selection for flooding tolerance. The use of multivariate analysis techniques and selection indices may help define easily measurable discriminant traits and identify more tolerant genotypes.

This study aimed to identify morphoagronomic traits that discriminate waterlogging tolerance in tropical forage grasses and to assess the performance of genotypes with contrasting responses under controlled conditions, providing practical criteria for early-stage selection in breeding programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

This study was conducted at Embrapa Acre, located in Rio Branco, Acre (latitude 9°58′22″ S; longitude 67°48′40″ W; altitude 159 m above sea level). The region has an average annual precipitation of 2022 mm, an average annual temperature of 25.46 °C, and an average relative humidity of 85.2% [

26].

2.2. Plant Material and Experimental Design

Between 2019 and 2021, four experiments were conducted in a controlled environment (screen house) using

M. maximus and

Urochloa spp. genotypes with contrasting tolerance levels to Marandu Death Syndrome (MDS) (

Table 1).

The plants were grown in a substrate composed of soil and sand, which were chemically analyzed separately (

Table 2). The soil was collected from the surface layer (0–20 cm) of a Latosol in an agricultural area of the experimental field at Embrapa Acre. After being sieved and dried, it was mixed with washed and dried sand in a 1:1 ratio, with no mineral fertilizer added.

All genotypes were obtained from seeds provided by Embrapa Beef Cattle, except for Ub001, which was propagated from cuttings collected from clumps in the experimental field of Embrapa Acre. The seeds were germinated in trays filled with a substrate composed of ashes and decomposed pine bark. Ten days after sowing, three uniform and similarly vigorous seedlings were transplanted into 5-L plastic pots containing 5 kg of substrate. The Ub001 seedlings (tillers with 10 cm and the same number of leaves) were collected and directly planted in triplicate in the pots on the same day as the seedling transplant. After ten days, plants were thinned to one per pot, retaining the most vigorous and uniform individual in each pot. The plants were then allowed to grow for another ten days before the imposition of water availability regimes. Prior to the initiation of the water treatments, pots were irrigated until reaching 90% of the pot capacity, monitored daily using a digital scale. This percentage was calculated based on the water mass retained at 100% of pot capacity.

Pot capacity was determined before the beginning of each experiment through gravimetric drainage. In four pots, 5 kg of dry substrate were placed over 500 g of gravel (granulometry between 19 mm and 25 mm). Pots were weighed to record the initial weight (IW). Then, water was added until complete saturation of the substrate. Pots were left on the bench for free drainage and weighed every 2 h during the first 10 h, with a final weighing after 24 h. To prevent water loss by evapotranspiration, the pots were sealed with plastic film. After full drainage, pots were weighed again to register the final weight (FW). Pot capacity (PC) was calculated using the equation PC = FW − IW.

Experiments 1 and 3 were conducted in a completely randomized design, while Experiments 2 and 4 followed a randomized block design. All experiments followed a factorial combination of five genotypes and two water availability conditions (waterlogged and well-drained), with four replications. Twenty days after transplanting, the genotypes were subjected to two water availability regimes: in Experiments 1 and 3, the well-drained treatment (control) was maintained at 90% of pot capacity, and in the flooded treatment, a 3 cm water layer was imposed above the soil surface. In Experiments 2 and 4, the control treatment was maintained at 80% of pot capacity and the flooded treatment at 120% of pot capacity (approximately 1 cm water layer above the soil surface). The 3 cm water layer used in Experiments 1 and 3 followed the methodology classically adopted in waterlogging studies with tropical forage grasses [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], ensuring comparability with previous research. In contrast, the 1 cm water layer imposed in Experiments 2 and 4 was chosen to better simulate the shallow water accumulation typically observed in poorly drained pastures affected by Marandu Death Syndrome under field conditions. This adjustment allowed us to evaluate whether a milder flooding level would improve the discrimination of genotypic responses under more realistic environmental conditions. The levels of 80%, 90%, and 120% of pot capacity were determined as fractions of 100% of PC. In the waterlogged treatment, water drainage was prevented by placing the pots into other containers with sealed drainage using plastic bags.

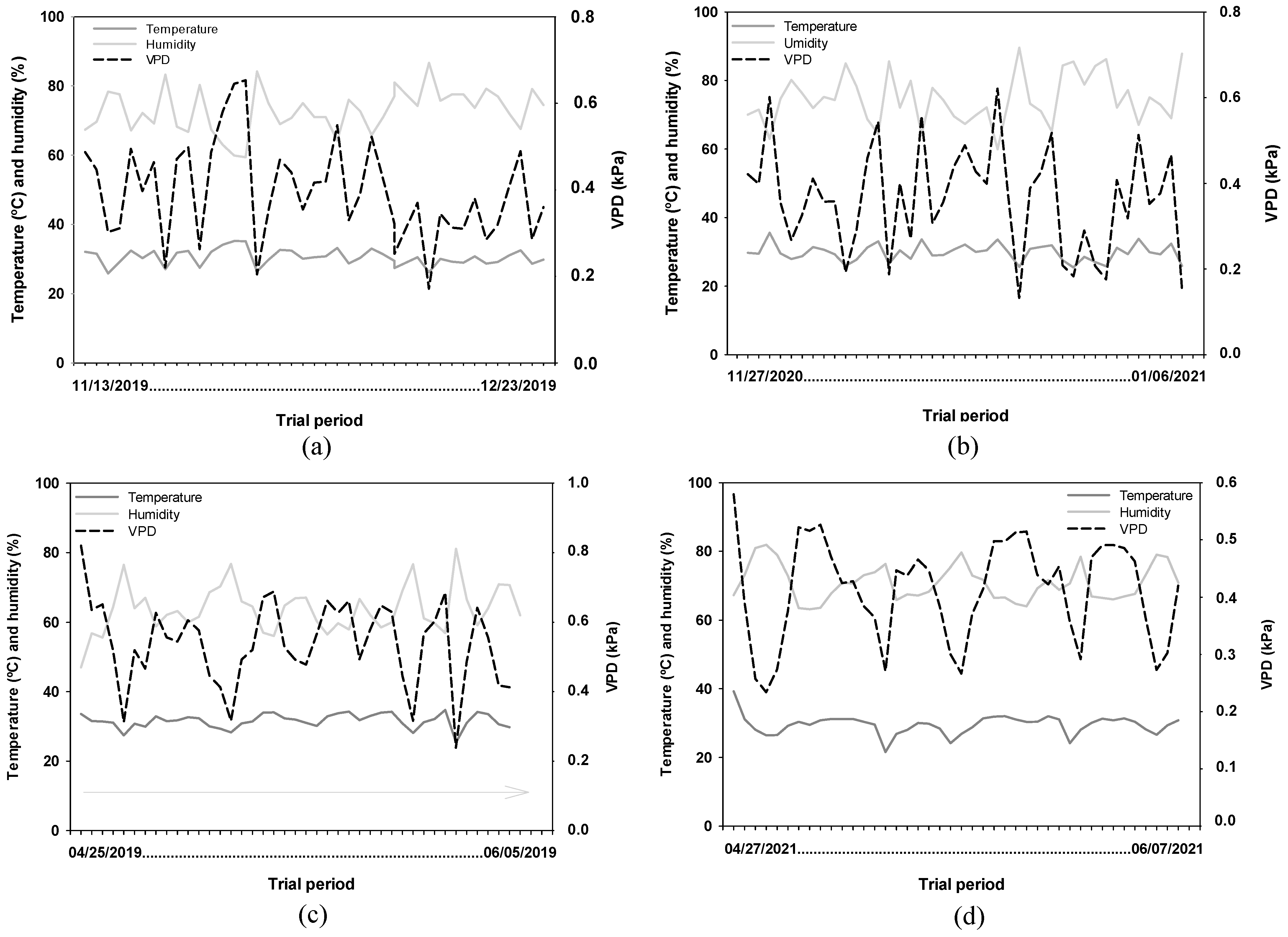

In each experiment, temperature and humidity inside the screen house were recorded, and vapor pressure deficit was calculated according to the Tetens equation [

29]. Although the experiments took place in different years and seasons, they were conducted in a greenhouse (semi-controlled environment), which minimized the influence of external factors such as precipitation. The daily environmental variation (temperature, relative humidity, and VPD) for each experiment is shown in

Figure 1. Despite being carried out in a semi-controlled environment and in different years, the statistical analyses were performed independently, and no cross-experiment comparisons were made.

2.3. Plant Measurements

Morphoagronomic traits, SPAD index, membrane damage, relative water content, and physiological traits related to gas exchange were evaluated once, after 21 days of growth under well-drained or waterlogged conditions. This treatment period followed the methodology developed by CIAT [

30], which describes a screening protocol in which

Urochloa plants are grown under controlled conditions and subsequently subjected to 21 days of continuous waterlogging, allowing the assessment of key morphophysiological traits, including green leaf biomass, SPAD index, and photosynthetic performance.

The number of green, yellowed, and senescent leaves was counted on fully expanded leaves per pot, and the totals were summed to obtain the total leaf number. The number of live and dead tillers was determined by counting green and dry tillers per pot, respectively.

Leaf elongation rate was measured according to Dias-Filho and Carvalho [

16]. The SPAD (Soil Plant Analysis Development) index was assessed with three consecutive measurements on the middle third of three fully expanded leaves using a Minolta SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter [

31].

At the end of the experiment, the dry mass of leaves, stems, and roots were determined by cutting the aerial biomass at soil level and separating leaves (leaf blades) and stems (including leaf sheaths) at the ligule junction. The substrate was removed from the roots with running water. Samples were dried in an oven at 65 °C and weighed after 72 h. Total dry mass was calculated as the sum of the dry masses of leaves, stems, and roots.

Membrane damage and relative water content analyses were performed only in Experiments 1 and 3, following the procedures described by Liu et al. [

32], with modifications.

For membrane damage (MD) evaluation, ten leaf discs were taken from a fully expanded leaf and immersed in 10 mL of deionized water for 8 h. Subsequently, the conductivity of the suspension was measured using a benchtop conductivity meter calibrated with a standard solution, obtaining the first conductivity reading (C1). Then, the discs were incubated in a water bath at 100 °C for 1 h. After cooling, electrical conductivity was measured again (C2). Membrane damage was calculated as follows: MD = (C1/C2) × 100.

For relative water content (RWC) analysis, 100 mg of leaf discs from the same leaf used for MD were weighed to obtain fresh mass (FM). Discs were immersed in 20 mL of deionized water in Petri dishes for 24 h at 4 °C in darkness. After this period, discs were weighed to obtain turgid mass (TM). Subsequently, discs were dried in an oven at 65 °C with forced air circulation until constant weight was achieved and then weighed to obtain dry mass (DM). Finally, RWC was calculated by the expression: RWC = [(FM − DM)/(TM − DM)] × 100.

Gas exchange measurements were always performed in the morning between 9:00 and 11:00 a.m. using an infrared gas analyzer (IRGA; portable LI-6400xt model, LI-COR Biosciences Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). Measurements were taken on a fully expanded young leaf blade. Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in the cuvette was maintained at 1200 μmol photons m−2 s−1, atmospheric CO2 concentration at 400 ppm, and temperature at 30 °C. The following parameters were evaluated: net photosynthesis (Pn), stomatal conductance (gs), leaf transpiration (E), and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci). Carboxylation efficiency (CE) and water use efficiency (WUE) were calculated as the ratios Pn/Ci and Pn/E, respectively.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.1.3 [

33]. Principal component analyses (PCA) were conducted using the FactoMineR package version 2.4 [

34] to select variables and evaluate the distance among genotypes. Analyses were based on the relative average percentage (RAP) between plants under control treatment (CT) and waterlogging treatment (WT) within the same genotype (RAP = WT × 100/CT) for all variables except total leaf number and total dry mass.

After performing PCA with all variables, variable selection was conducted with the main criterion being the retention of variance explained by the first two principal components above 70% [

35,

36,

37]. Additionally, biological relevance and/or ease of evaluation were considered. Thus, variables that were difficult to assess and/or had low biological importance were excluded whenever possible.

Standardized Euclidean distances from the genotype scores for the first two principal components were calculated using the R function dist. These distances were used to generate clusters via the Tocher optimization method in the MultivariateAnalysis package version 0.4.4 [

38].

The sum of ranks index [

39] was applied to classify genotypes according to their level of tolerance to soil waterlogging, using the R function rank. Classification was carried out with two sets of variables selected from PCA: morphoagronomic variables (MAV) and morphoagronomic plus physiological variables (MAV + PV). Spearman correlation coefficients between the sum of ranks of MAV, PV, and MAV + PV were obtained using the R function cor.test.

3. Results

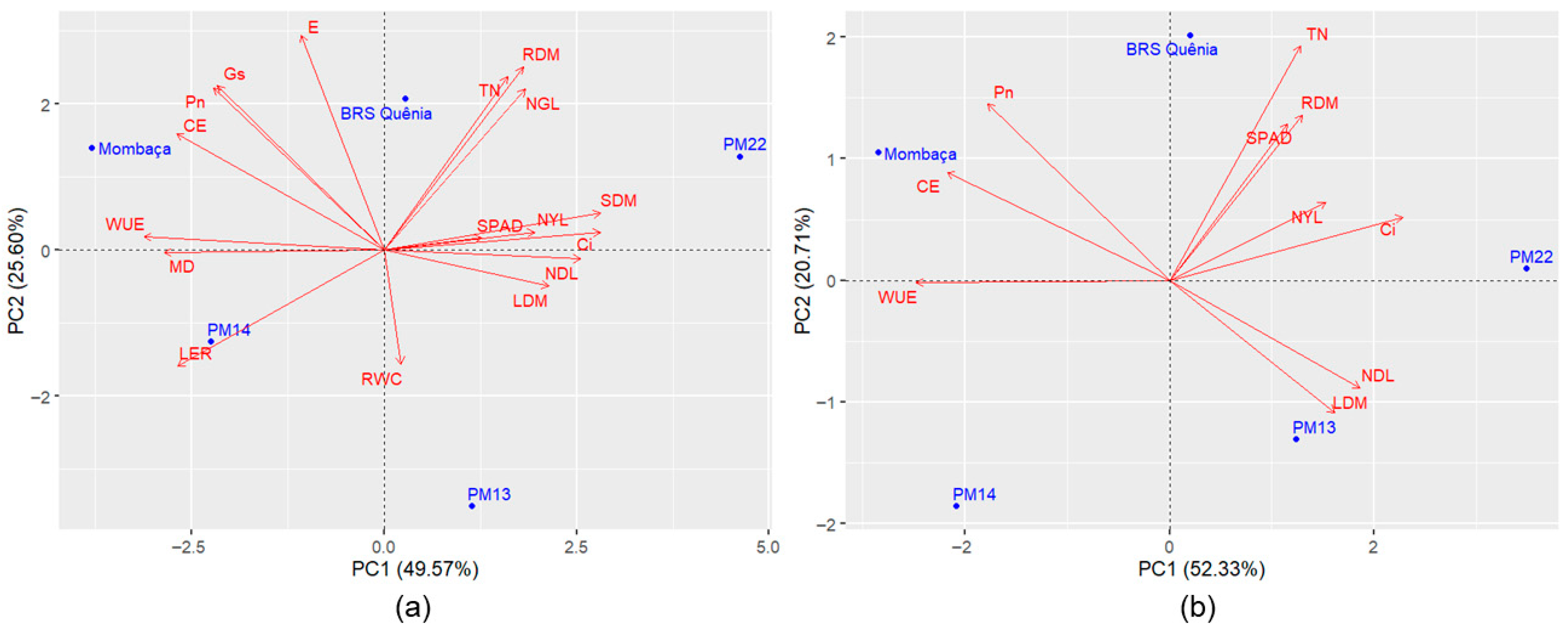

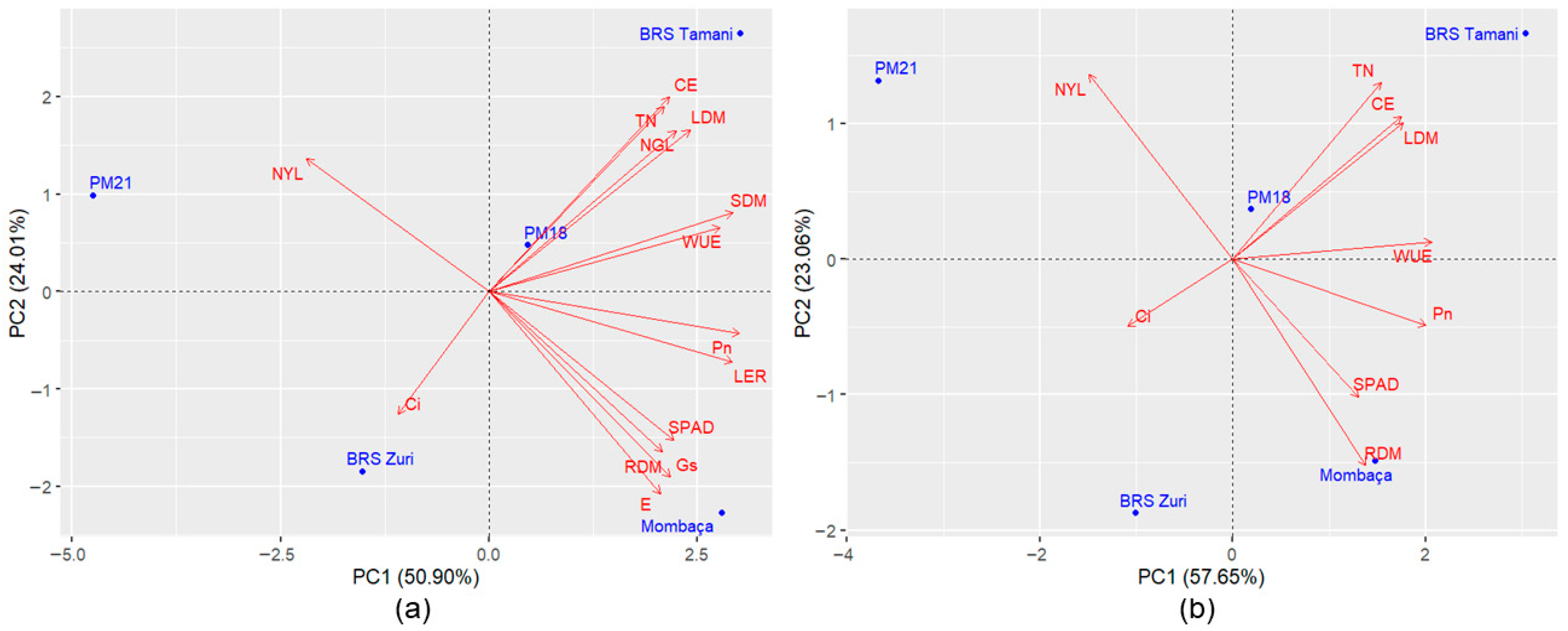

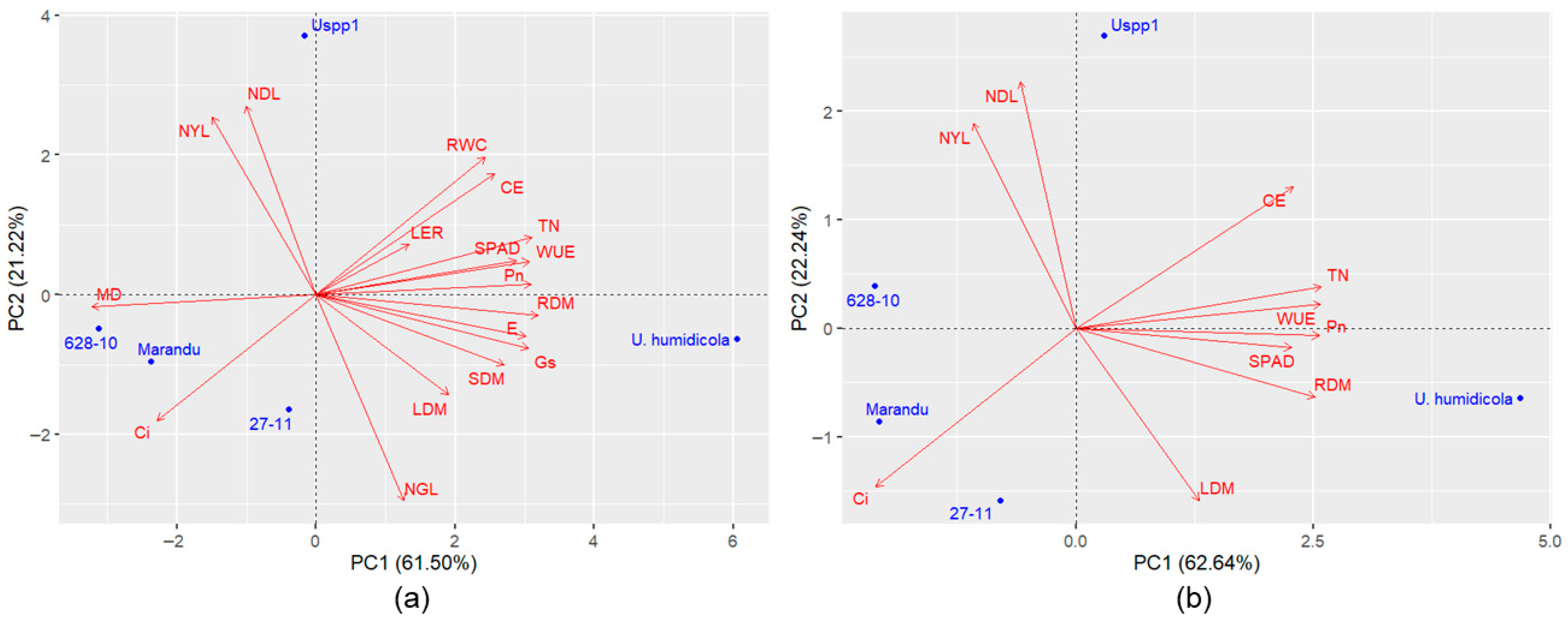

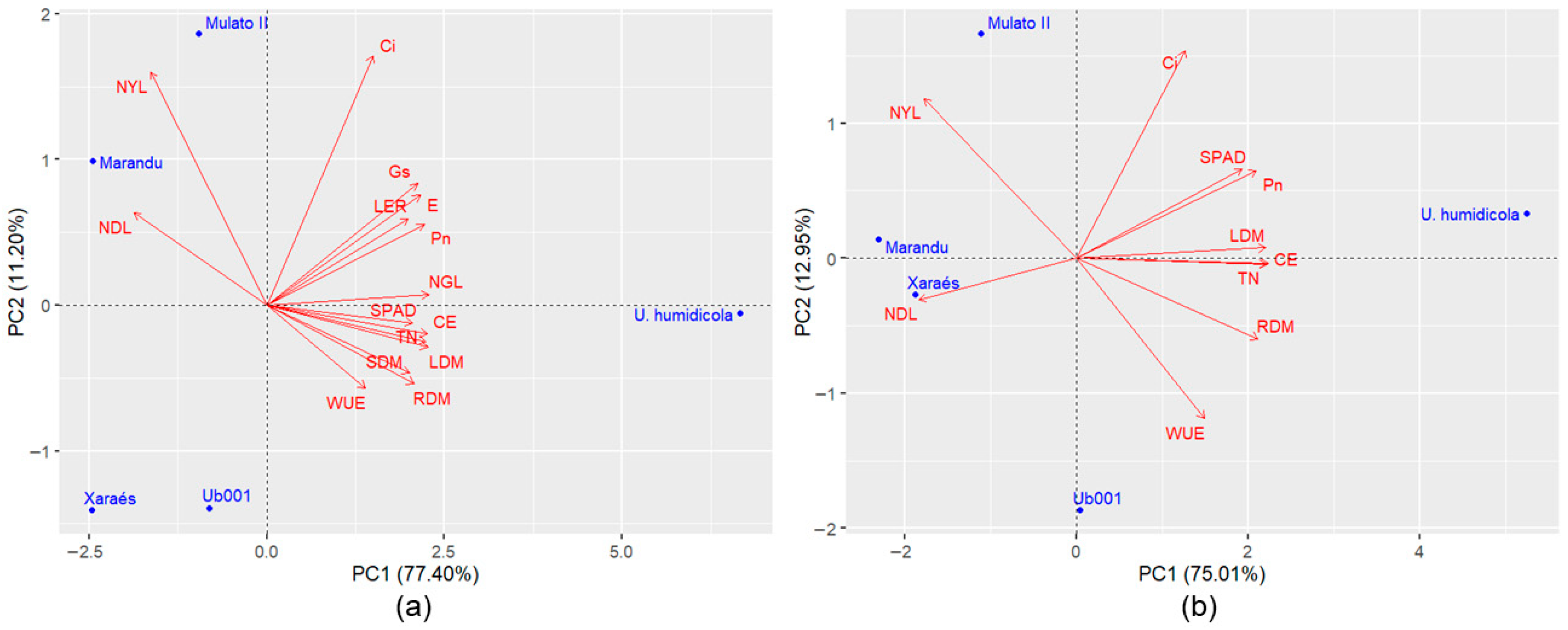

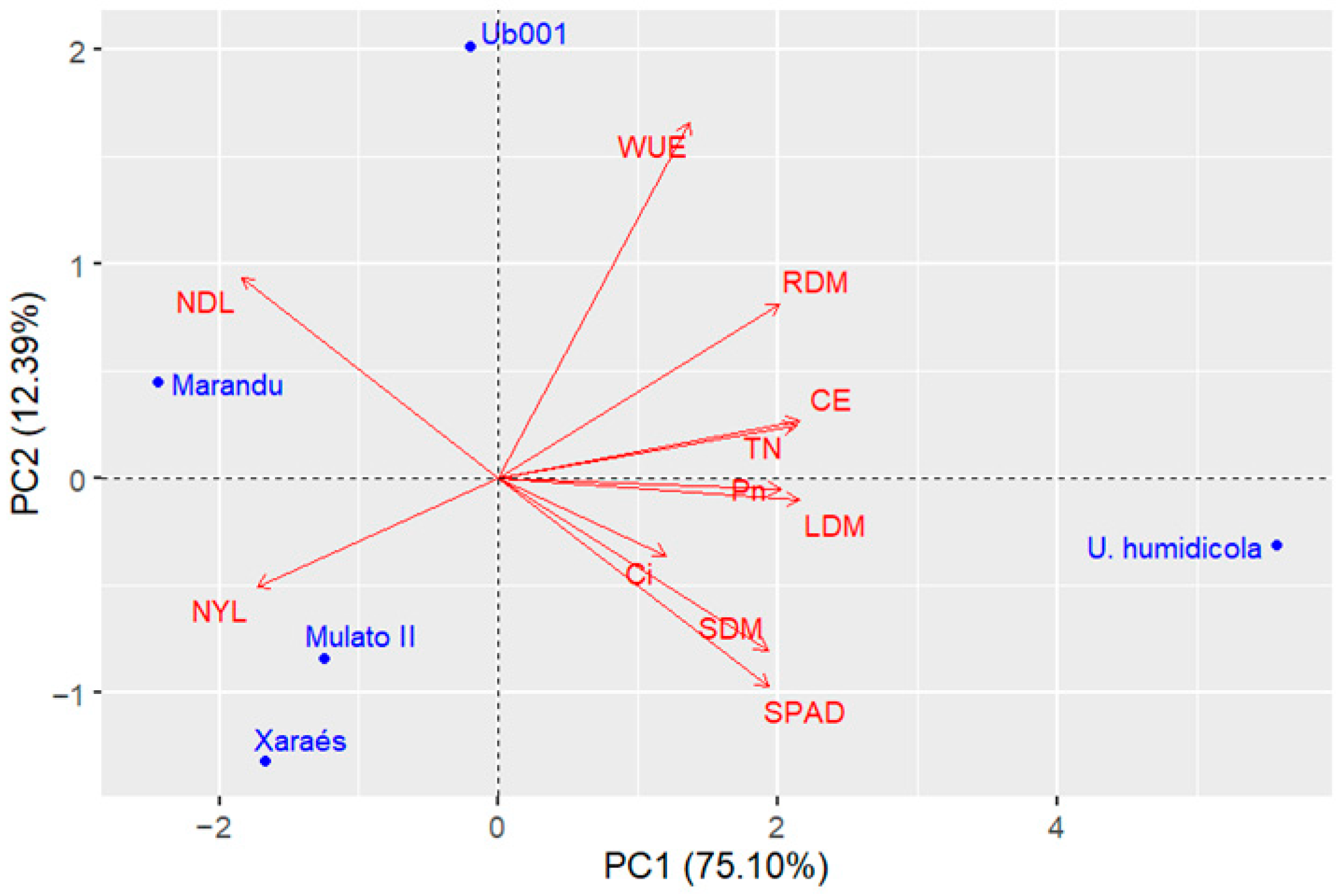

Principal component analyses revealed variation among genotypes for tolerance to waterlogging. The first two components of the dataset containing all traits accounted for 75.17% to 88.60% of the total variation (

Figure 2a,

Figure 3a,

Figure 4a and

Figure 5a), indicating that graphical interpretation could be performed based on the two-dimensional dispersion.

Based on the PCA including all variables, a variable reduction process was conducted. The main criterion adopted for this step was the preservation of the variance retained in the first two principal components, maintaining an explanatory power above 70%. Additionally, the difficulty of measurement and the biological relevance of each trait were also considered. Among the evaluated traits, the number of green leaves, stem dry mass, leaf elongation rate, relative water content, membrane damage, transpiration, and stomatal conductance were excluded.

After variable reduction, the accumulated variance in the first two principal components was slightly reduced in Experiment 1 (by 2.13%) (

Figure 2a,b) and in Experiment 4 (by 0.64%) (

Figure 5a,b); however, retained variance remained above 70%. In Experiments 2 and 3 (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), the accumulated variance in the first two principal components increased by 2.16% and 0.57%, respectively. The genotype dispersion pattern in Experiments 1, 2, 3, and 4 was minimally altered after variable reduction. In the

M. maximus experiments, the genotypes shifted slightly within the two-dimensional space, but the distances between them remained nearly unchanged (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). The most notable changes, albeit minor, were observed in the experiments with

Urochloa spp. genotypes. In Experiment 3, after variable reduction, hybrid 628-10 became more distant from cv. Marandu (

Figure 4), while in Experiment 4, cv. Xaraés moved away from accession Ub001 and became closer to cv. Marandu (

Figure 5). Due to this last change in

Urochloa spp. experiment, new analyses were conducted, and it was found that the inclusion of the variable stem dry mass maintained a dispersion pattern like that of

Figure 5a, with ‘Xaraés’ remaining more distant from ‘Marandu’ (

Figure 6). For the other experiments, the inclusion of this trait caused minimal changes in the graphical dispersions of PCA. However, in the subsequent cluster and ranking analyses using the selection index, the results were not consistent, indicating that it is more appropriate not to include stem dry mass in all experiments. It is worth noting that this variable may be important depending on the population under analysis. Therefore, validation trials with populations composed of a larger number of genotypes are recommended. Despite these differences, in general, the variable reduction process proved effective, indicating that the excluded traits were not essential for assessing genotype divergence.

Using Tocher’s optimization method based on the standardized Euclidean distance of principal component scores, the genotypes were clustered into distinct groups. The

M. maximus genotypes were separated into three groups in both experiments (

Table 3 and

Table 4). In Experiment 1, Group I included ‘Mombaça’ and ‘BRS Quênia’, Group II comprised PM13 and PM22, and Group III contained PM14. In Experiment 2, Group I was composed of three genotypes (‘Mombaça’, ‘BRS Zuri’, and PM18), while Groups II (‘BRS Tamani’) and III (PM21) each contained a single genotype. Based on the biplots, no clear clustering pattern was observed for these genotypes (

Figure 2b and

Figure 3b).

In Experiments 3 and 4, the

Urochloa spp. genotypes were separated into two groups using the Tocher optimization method (

Table 5 and

Table 6), with

U. humidicola allocated to a group distinct from the other genotypes. The high level of waterlogging tolerance exhibited by

U. humidicola compared to the others likely hindered the Tocher method from effectively discriminating among the remaining

Urochloa spp. genotypes. Consequently, the groups formed by these genotypes (Group I in Experiments 3 and 4) were subjected to additional clustering analyses to form subgroups.

When analyzing

Urochloa spp. genotypes without

U. humidicola, two groups were formed by Tocher’s method in Experiment 3. Cultivar Marandu and the hybrids 27-11 and 628-10 were clustered into one group, while Uspp1 was allocated to a separate group (

Table 7), a result consistent with the two-dimensional dispersion observed in

Figure 4b. In Experiment 4, Tocher’s method also resulted in the formation of two groups, with one being a single group composed of the Ub001 accession, and the other including the remaining genotypes (

Table 8). Graphical dispersion analysis (

Figure 5b) revealed greater proximity between cv. Marandu and cv. Xaraés. However, according to Tocher’s method, the hybrid Mulato II was clustered with these two genotypes, likely due to the large distance exhibited by accession Ub001 in relation to all other genotypes.

Tocher’s method allowed greater objectivity in genotype discrimination when compared to PCA, mainly due to its ability to group

M. maximus genotypes (

Table 3 and

Table 4), which did not show a clear clustering pattern in the PCA biplots (

Figure 2b and

Figure 3b). Moreover, Tocher’s method enabled the subdivision of

Urochloa spp. genotypes allocated to Group I in Experiments 3 and 4. Therefore, these techniques were complementary, as the standardized Euclidean mean distances used in Tocher’s method were calculated based on PC1 and PC2.

The

M. maximus and

Urochloa spp. genotypes were ranked according to their tolerance to soil waterlogging using two sets of variables selected in the principal component analysis: morphoagronomic (MAV) and morphoagronomic plus physiological (MAV + PV). The ranking results based on the Rank Sum Index are presented in

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12.

When comparing the genotype ranking based solely on morphoagronomic variables with the classification that also included physiological variables, differences were observed in the ranking of PM14 and PM22 in Experiment 1 (

Table 9), and between ‘BRS Zuri’ and PM18 in Experiment 2 (

Table 10), indicating that physiological variables influenced the ordering of these genotypes. Although these changes were attributed to the influence of physiological variables, the Spearman correlation coefficient showed that morphoagronomic variables can be used for the indirect selection of physiological traits, as the correlations between these two sets of variables were all significantly high (

p < 0.05) across the four experiments (

Table 13).

In the experiments with

M. maximus, cv. Mombaça was classified as the most tolerant to waterlogging, followed by cv. BRS Quênia and cv. BRS Tamani in Experiments 1 and 2, respectively (

Table 9 and

Table 10). On the other hand, genotypes PM13 (Experiments 1) and PM21 (Experiment 2) had the lowest tolerance to the stress, according to MAV and MAV + PV.

In Experiments 3 and 4, regardless of the set of variables, the index confirmed the high tolerance of

U. humidicola to waterlogging (

Table 11 and

Table 12). Marandu was found to have the lowest tolerance in all scenarios, tying with hybrid 628-10 in Experiment 3. Using the Tocher method, these genotypes were allocated to the same group (

Table 7), confirming that the tolerance of hybrid 628-10 was low and similar to that of cv. Marandu. Uspp1 was ranked higher than hybrid 27-11 in both sets of variables. Using Tocher’s method, these genotypes were allocated to distinct groups.

In Experiment 4, accession Ub001 demonstrated intermediate tolerance, being the second highest-ranked genotype, followed by cv. Xaraés, hybrid Mulato II, and cv. Marandu. According to Tocher’s analysis, these last three genotypes showed low distances from each other, as they comprised the same group (

Table 8) and divergence with accession Ub001, which was separated into a separate group.

5. Conclusions

The physiological traits—photosynthetic rate, internal CO2 concentration, carboxylation efficiency, and water use efficiency—are recommended as selection criteria for identifying M. maximus and Urochloa spp. genotypes tolerant to waterlogged soils.

The morphoagronomic traits—number of yellow and senescent leaves, number of tillers, SPAD index, leaf dry mass, and root dry mass—are recommended as selection criteria for identifying M. maximus and Urochloa spp. genotypes tolerant to waterlogging under controlled conditions and can also be used for the indirect assessment of physiological traits.

Among the M. maximus genotypes evaluated, cv. Mombaça is the most waterlogging tolerant, while PM13 and PM21 are the least tolerant.

Among the Urochloa spp. genotypes evaluated, U. humidicola is the most tolerant to this stress. Xaraés, Uspp1, hybrid 27-11, and Ub001 showed intermediate tolerance. The hybrids Mulato II and 628-10 were classified as having low tolerance to waterlogging, and cv. Marandu exhibited very poor tolerance.

The use of U. humidicola cv. Tully as a control in experiments with Urochloa spp. genotypes should be performed with caution, as the high tolerance level of this species may impair the identification of tolerance levels in other genotypes.

The classification of forage grass genotypes for waterlogging tolerance, based on pot experiments under controlled conditions, does not necessarily reflect their degree of tolerance to Marandu Death Syndrome when grown in poorly drained soils under grazing conditions.

Future studies may include field validation in poorly drained soils and under grazing conditions, since responses under controlled conditions may not fully capture the multifactorial nature of MDS. Furthermore, complementary analyses, such as detailed anatomical characterization of the roots (e.g., aerenchyma development in M. maximus), evaluation of oxidative enzyme activity, and analysis of gene expression patterns associated with hypoxia tolerance, may help elucidate the underlying mechanisms responsible for the contrasting responses observed among the genotypes.