Compatibility Between Beauveria bassiana and Papain and Their Synergistic Potential in the Control of Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain Acquisition

2.2. Preparation of Solutions

2.3. Compatibility Assessment Between Conidia and Papain

2.4. Determination of Papain Residual Activity After Incubation with Conidia

2.5. Bioassays with Tenebrio molitor

2.6. Evaluation of Morphological Alterations in Larvae and Pupae

2.7. Reisolation and Morphological Characterization of Beauveria bassiana

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Conidial Viability

3.2. Determination of Residual Papain Activity After Incubation with Conidia

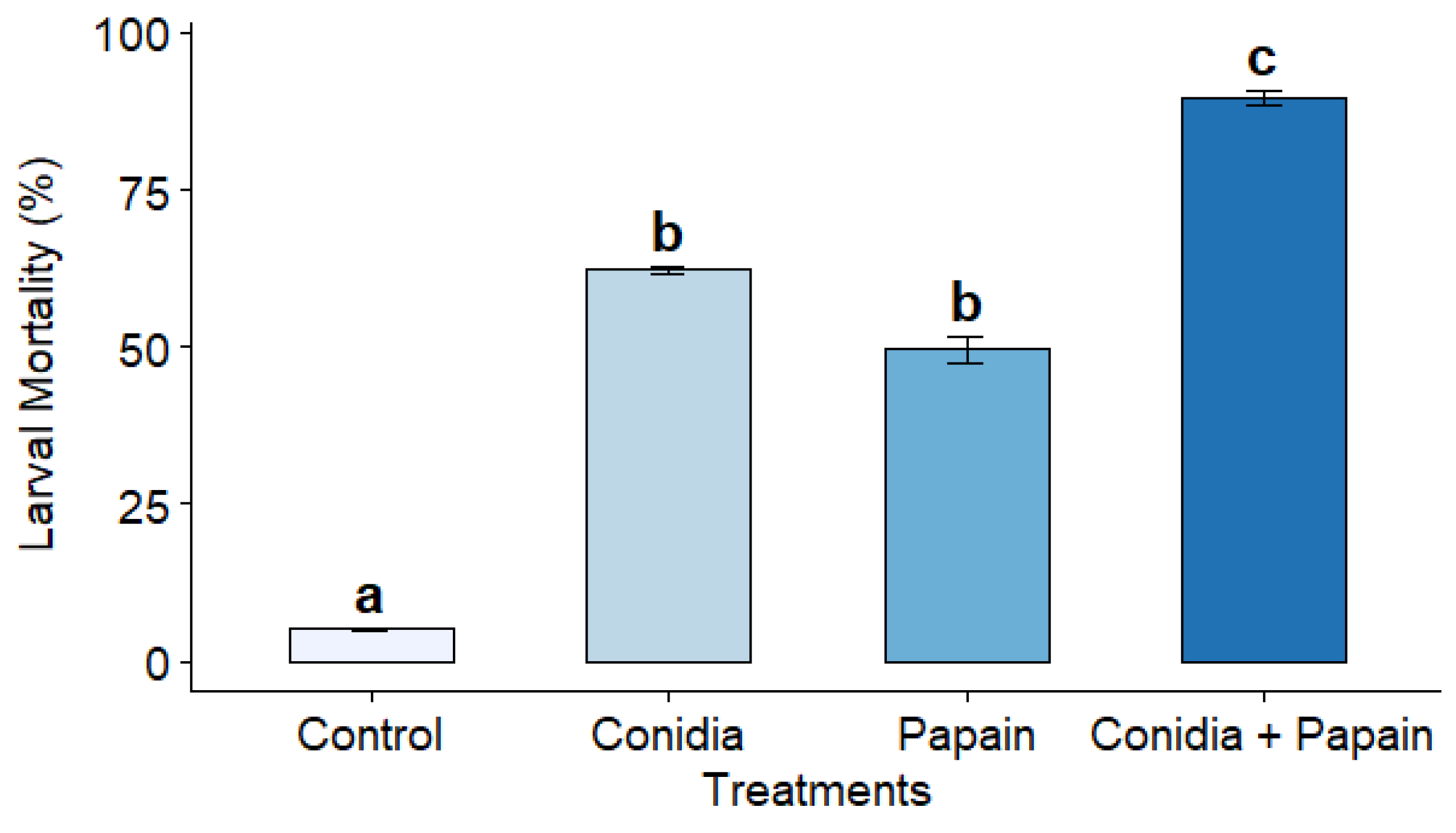

3.3. Bioassays with Pupae and Larvae of Tenebrio molitor

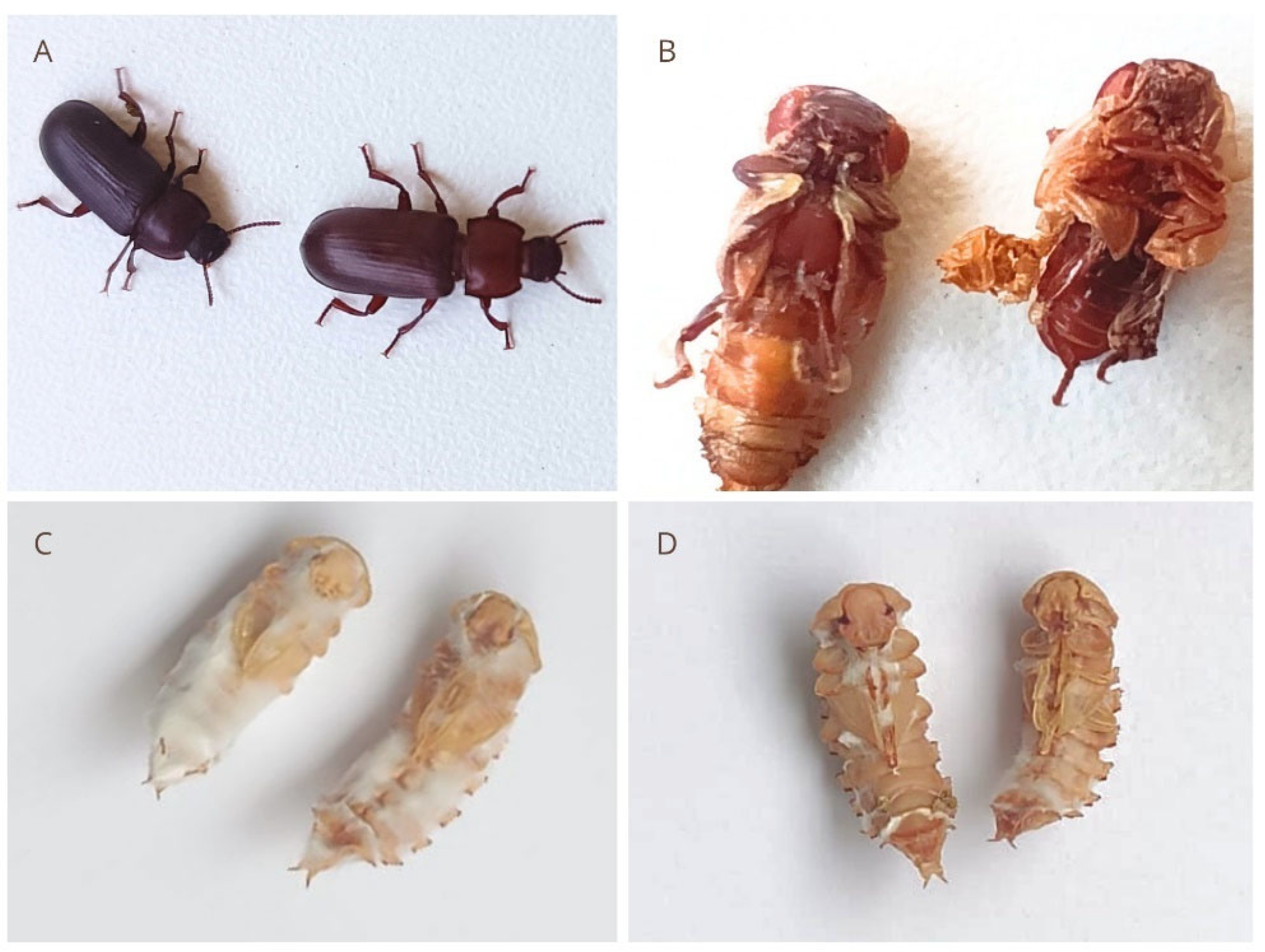

3.4. Effects on Larval and Pupal Morphology

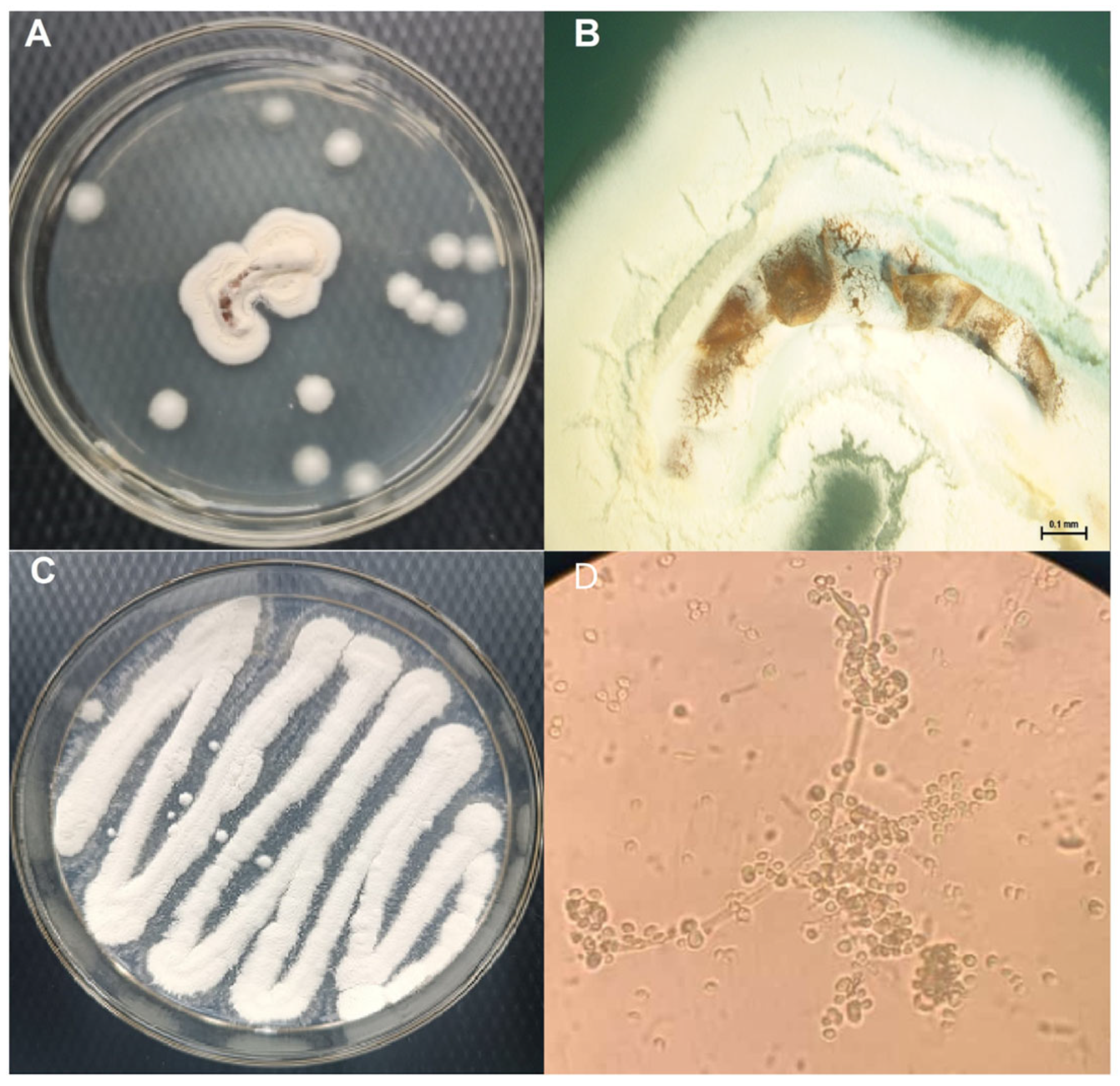

3.5. Morphological Analysis and Reisolation of Beauveria bassiana

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, J.; Xiao, F.; Ojo, J.; Chao, W.H.; Ahmad, B.; Alam, A.; Karim, S.A. Insect resistance to insecticides: Causes, mechanisms, and exploring potential solutions. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 118, e70045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrão, J.E.; Plata-Rueda, A.; Martínez, L.C.; Zanuncio, J.C. Side-effects of pesticides on non-target insects in agriculture: A mini-review. Sci. Nat. 2022, 109, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angon, P.B.; Mondal, S.; Jahan, I.; Datto, M.; Antu, U.B.; Ayshi, F.J.; Islam, M.S. Integrated pest management (IPM) in agriculture and its role in maintaining ecological balance and biodiversity. Adv. Agric. 2023, 2023, 5546373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.; Ravi, G. Role of artificial intelligence in pest management. Curr. Top. Agric. Sci. 2022, 7, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Smagghe, G.; Liu, T.-X. Interactions between entomopathogenic fungi and insects and prospects with glycans. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, Q.; Wang, D.; Zou, W.-Q.; Tang, D.-X.; Hongthong, P.; Yu, H. Species diversity and virulence potential of the Beauveria bassiana complex and Beauveria scarabaeidicola complex. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 841604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada-Moraga, E.; González-Mas, N.; Yousef-Yousef, M.; Pérez-González, S.; Castillo, J.; Landa, B.B. Key role of environmental competence in successful use of entomopathogenic fungi in microbial pest control. J. Pest Sci. 2024, 97, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, S.; Yadav, P.K. Entomopathogenic fungi and their relevance in sustainable agriculture: A review. Cogent Food Agric. 2023, 9, 2180857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, T.K.; Silva, A.T.d.; Soares, F.E.d.F. Fungi-Based Bioproducts: A Review in the Context of One Health. Pathogens 2025, 14, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivekanandhan, P.; Swathy, K.; Sarayut, P.; Patcharin, K. Classification, biology and entomopathogenic fungi-based management. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1443651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.M.; de Freitas Soares, F.E. Entomopathogenic fungi hydrolytic enzymes: A new approach to biocontrol? J. Nat. Pestic. Res. 2023, 3, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, K.; Hirayama, C.; Nakamura, M.; Tateishi, K.; Tamura, Y.; Hattori, M.; Kohno, K. Papain protects papaya trees from herbivorous insects: Role of cysteine proteases in latex. Plant J. 2004, 37, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, H.L.B.; Alves, J.C.S.; Gladenucci, J.; Marucci, R.C.; Soares, F.E. Nematocidal and insecticidal activity of proteases from Carica papaya and Ananas comosus. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Kaushik, R.; Chawla, P.; Manna, S. Exploring the extraction and functional properties of papain. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 1533–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, H.L.B.; Braga, F.R.; Soares, F.E.F. Potential of plant cysteine proteases against crop pests and animal parasites. J. Nat. Pestic. Res. 2023, 6, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamaki-Sotiraki, C.; Rumbos, C.I.; Athanassiou, C.G. From a stored-product pest to a promising protein source: A U-turn of human perspective for the yellow mealworm Tenebrio molitor. J. Pest Sci. 2025, 98, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathas, I.G.; Sakellaridis, A.C.; Papadelli, M.; Krokida, A.M.; Athanassiou, C.G. The effects of insect infestation on stored products. Foods 2023, 12, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, G.U.; Flint, S.D.; Miller, C.D.; Anderson, A.J.; Roberts, D.W. Both solar UVA and UVB radiation impair conidial culturability and delay germination in the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 74, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, F.R.; Araújo, J.V.; Soares, F.E.F. Optimizing protease production from an isolate of the nematophagous fungus Duddingtonia flagrans using response surface methodology and its larvicidal activity on horse cyathostomins. J. Helminthol. 2011, 85, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.M.; Fernandes, É.K.K.; Kim, J.S.; Soares, F.E.F. The combination of enzymes and conidia of entomopathogenic fungi against Aphis gossypii nymphs and Spodoptera frugiperda larvae. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, M.; Ayres, J.R.M.; Ayres, D.L.; Santos, A.S. Aplicações Estatísticas nas Áreas Biomédicas; Mamirauá/CNPq: Brasília, Brazil; Belém, Brazil, 2003; 290p. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Haro, L.; Prince, G.; Granja-Travez, R.S.; Chandler, D. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of fifty strains of Beauveria spp. (Ascomycota, Cordycipitaceae) fungal entomopathogens from diverse geographic origins against the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 5064–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, J.C.; Albuquerque, A.C.; Lima, E.L.A. Viability of Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill. reisolated from eggs, larvae and adults of Anthonomus grandis (Boheman) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) infected artificially. Arq. Inst. Biol. 2005, 72, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.F.; Mohamed, S.S.A.; Sweilem, M.A.; El-Sharkawy, R.M.; El-Khawaga, O.E.A.A. Effect of storage temperatures on the pathogenicity of Beauveria bassiana formulations against the cottonleaf worm, Spodoptera littoralis (Boisduval) (Lepidoptera). J. Basic Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Riaño, J.L.; Torres-Torres, L.A.; Santos-Díaz, A.M.; Grijalba-Bernal, E.P. Compatibility of B. bassiana with agrochemicals. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 39, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarin, G.M.; Golo, P.S.; Ribeiro-Silva, C.S.; Muniz, E.R.; Franco, A.O.; Kobori, N.N.; Fernandes, É.K.K. Advances in submerged fermentation of entomopathogenic fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channamade, C.; Raju, J.M.; Vijayaprakash, S.B.; Bora, R.; Shekhar, N.R. Promising approach on chemical stability enhancement of papain by encapsulation system: A review. J. Young Pharm. 2021, 13, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Lucca, R.A.; Andrade, S.S.; Ferreira, R.S.; Sampaio, M.U.; Oliva, M.L.V. Unfolding Studies of the Cysteine Protease Baupain, a Papain-Like Enzyme from Leaves of Bauhinia forficata: Effect of pH, Guanidine Hydrochloride and Temperature. Molecules 2014, 19, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llerena-Suster, C.R.; José, C.; Collins, S.E.; Briand, L.E.; Morcelle, S.R. Investigation of the structure and proteolytic activity of papain in aqueous miscible organic media. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, Z.; Homaei, A.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Enhanced stability of papain at extreme pHs and temperatures by its immobilization on cellulose nanocrystals coated with polydopamine. Process Biochem. 2024, 146, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, A.; Nowak, M.; Różalska, S. Entomopathogenic fungi: Unconventional applications. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, H.; Li, W.; Cheng, P.; Gong, M. The toxins of Beauveria bassiana and strategies to improve virulence. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 705343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.C.; Gomes, E.H.; Puentes, L.B.F.; Rodrigues, L.M. D. flagrans and proteolytic extract in sheep cultures. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 3423–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.E.; Goettel, M.S.; Blackwell, M.; Chandler, D.; Jackson, M.A.; Keller, S.; Koike, M.; Maniania, N.K.; Monzón, A.; Ownley, B.H.; et al. Fungal entomopathogens: New insights on their ecology. Fungal Ecol. 2009, 2, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.A.; Pell, J.K. Entomopathogenic fungi as biological control agents. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 61, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettel, M.S.; Eilenberg, J.; Glare, T.R. Entomopathogenic fungi and their role in biological control. In Manual of Techniques in Invertebrate Pathology; Lacey, L.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 305–353. [Google Scholar]

- Zibaee, A.; Ramzi, S. Cuticle-degrading proteases of entomopathogenic fungi: From biochemistry to biological performance. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2018, 51, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, L.A.; Grzywacz, D.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Frutos, R.; Brownbridge, M.; Goettel, M.S. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: Back to the future. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 132, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B. Botanical insecticides, deterrents, and repellents in modern agriculture and an increasingly regulated world. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Urquiza, A.; Keyhani, N.O. Immune evasion and growth within the hemocoel. In Genetics and Molecular Biology of Entomopathogenic Fungi; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, G. Review on safety of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2007, 17, 879–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, S.; Sevim, A.; Sezgin, F.M.; Sevim, E. Isolation and characterization of Beauveria and Metarhizium spp. from walnut fields and their pathogenicity against the codling moth Cydia pomonella (L.) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2018, 28, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, R.J.S.; Charnley, A.K.; Cooper, R.M. Cuticle-degrading proteases of entomopathogenic fungi. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1986, 48, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humber, R.A.; Lacey, L.A. Identification of entomopathogenic fungi. In Manual of Techniques in Invertebrate Pathology, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bich, G.A.; Castrillo, M.L.; Kramer, F.L.; Villalba, L.L.; Zapata, P.D. Morphological and molecular identification of entomopathogenic fungi from agricultural and forestry crops. Floresta Ambiente 2021, 28, e20180086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P.M.; Cannon, P.F.; Minter, D.W.; Stalpers, J.A. Dictionary of the Fungi, 10th ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, R.A.; Evans, H.C.; Latgé, J.P. Atlas of Entomopathogenic Fungi; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alves, A.d.C.; Silva, A.C.; Silva, A.T.d.; Sales, N.K.L.; Mamani, R.C.C.; Figueroa, L.B.P.; Gomes, E.H.; de Souza, D.C.T.; Marucci, R.C.; Soares, F.E.d.F. Compatibility Between Beauveria bassiana and Papain and Their Synergistic Potential in the Control of Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Agrochemicals 2026, 5, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/agrochemicals5010002

Alves AdC, Silva AC, Silva ATd, Sales NKL, Mamani RCC, Figueroa LBP, Gomes EH, de Souza DCT, Marucci RC, Soares FEdF. Compatibility Between Beauveria bassiana and Papain and Their Synergistic Potential in the Control of Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Agrochemicals. 2026; 5(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/agrochemicals5010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlves, Amanda do Carmo, Ana Carolina Silva, Adriane Toledo da Silva, Nivia Kelly Lima Sales, Ruth Celestina Condori Mamani, Lisseth Bibiana Puentes Figueroa, Elias Honorato Gomes, Debora Castro Toledo de Souza, Rosangela Cristina Marucci, and Filippe Elias de Freitas Soares. 2026. "Compatibility Between Beauveria bassiana and Papain and Their Synergistic Potential in the Control of Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae)" Agrochemicals 5, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/agrochemicals5010002

APA StyleAlves, A. d. C., Silva, A. C., Silva, A. T. d., Sales, N. K. L., Mamani, R. C. C., Figueroa, L. B. P., Gomes, E. H., de Souza, D. C. T., Marucci, R. C., & Soares, F. E. d. F. (2026). Compatibility Between Beauveria bassiana and Papain and Their Synergistic Potential in the Control of Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Agrochemicals, 5(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/agrochemicals5010002