1. Introduction

The advent of microtumor and organoid technology in the field of cancer research has enabled the creation of three-dimensional cell cultures that closely mimic the architecture and functionality of human tissues. Microtumors derived from patient tumor cells offer a promising platform for the development of personalized therapies, as they retain the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of the original tumors [

1,

2]. This approach is particularly relevant for epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), a heterogeneous disease comprising various histological subtypes, each with distinct genetic and genomic profiles that can influence treatment response [

3,

4].

The development of preclinical models to investigate the tumor microenvironment (TME) and its response to targeted chemotherapy has garnered significant attention in cancer research. These models encompass a variety of systems, including traditional cell lines, mouse models, tissue cultures, and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs). While cell lines are widely utilized due to their convenience and reproducibility, they inadequately capture the intricate complexity of tumors, particularly the extracellular matrix (ECM) components and critical cell–cell interactions [

5]. PDX models, while advantageous in preserving the tumor microenvironment, present substantial challenges related to cost and the time required for establishment and experimentation [

6]. Despite these models being instrumental in assessing tumor responses, they often lack the personalized dimension necessary for effective patient-specific treatment strategies.

In this context, PDMs emerge as an alternative preclinical model. These three-dimensional (3D) cultures are capable of simulating the heterogeneity and diversity inherent in tumors, exhibiting a high degree of genotypic and phenotypic fidelity to the original clinical specimens [

2]. Additionally, the relatively rapid generation of microtumors allows for timely therapeutic evaluations, offering significant advantages over traditional models in the pursuit of effective and individualized cancer therapies [

7].

EOC is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide, characterized by a challenging prognosis due to late-stage diagnosis. In the United States, approximately 19,880 new cases of ovarian cancer were projected for 2025, with an estimated 12,810 deaths resulting from the disease [

8] and the overall five-year survival rate for women diagnosed with EOC being around 47%. Although survival varies significantly depending on the stage at diagnosis, early-stage patients have a survival rate exceeding 90%, while those diagnosed at an advanced stage face a much lower rate, often below 30% [

9,

10]. This stark disparity in survival rates underscores the critical need for novel therapeutic strategies to enhance treatment outcomes [

10].

The utilization of PDMs presents an opportunity to accurately predict individual responses to standard or experimental chemotherapeutic regimens. While microtumor testing has typically been applied in the evaluation of primary tumors, our model extends this application to samples that have undergone neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This advanced microtumor model harbors considerable potential for revealing new mechanisms of resistance while providing a valuable framework for designing novel clinical trials. Its implications are significant for both neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings, with the prospect of transforming treatment strategies and improving patient outcomes. Through this study, we aim to add to the growing body of literature advocating for the integration of microtumor and organoid technologies into clinical oncology. By leveraging this model, researchers can one day not only tailor therapeutic approaches but also evaluate the changes in the TME, explore resistance mechanisms, and discover potentially novel biomarkers in response to chemotherapy, both in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings. This can ultimately lead to more individualized cancer care that reflects the unique characteristics of each patient’s disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Tissue Collection

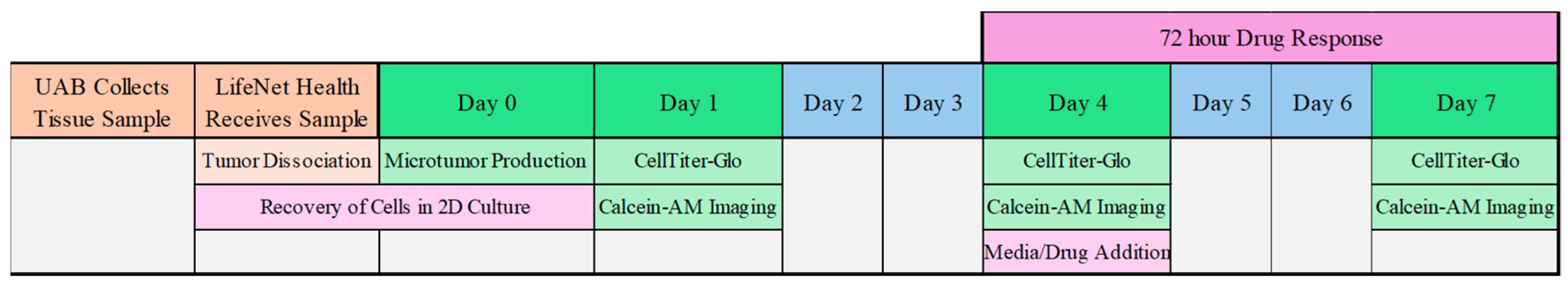

Fresh tissue specimens were obtained from patients undergoing primary or interval debulking surgery (IDS) for epithelial ovarian cancer EOC under IRB approval between October 2023 and May 2024 at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. All procedures were conducted with informed consent and in accordance with institutional guidelines. Tumor samples were collected, processed, and transported to the Patient Therapy Evaluation Service (PTES) Team at LifeNet Health (Virginia Beach, VA, USA) within 24 h of surgery (

Figure 1).

2.2. Tumor Dissociation

Ovarian tumors were measured, weighed, and minced prior to being placed in a C-tube (Miltenyi Biotec #130-093-237, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Dissociation was performed chemically using enzymes from a human tumor dissociation kit (Miltenyi Biotec #130-095-929) reconstituted in RPMI 1640 (Gibco #21870076, Grand Island, NY, USA) and physically using the gentleMACs Octo Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec #130-096-427). RHO/ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (StemCell Technologies #72304, St. Vancouver, BC, Canada) at a concentration of 10µM was added during dissociation. After chemical and physical dissociation, the tumor sample was filtered through 100 µm and 40 µm sterile cell strainers to remove undigested tissue. The filters were rinsed with sterile RPMI 1640 to ensure maximum cell yield. Red blood cells were lysed using ACK Lysis Buffer (Gibco #A1049201). The resulting cells were rinsed in 1× DPBS (Gibco #14190235) prior to counting. A small sample of cell suspension was collected and stained with AOPI (Revvity #CS2-0106-5ML, Waltham, MA, USA) prior to counting with a Nexcelom Cellometer. The final cell count was adjusted to remove dual-staining.

Positive Control Cell Line: SKOV-3 (ATCC #HTB-77, Manassass, VA, USA) was grown in DMEM/F-12 complete medium with 10% FBS, Penicillin-Streptomycin, L-Glutamine, and Amphotericin B (Corning #30003CF, Corning, NY, USA) before being collected with TrypLE. SKOV-3 was used in all experiments at passage 9.

2.3. Microtumor Production

Human placenta-derived ECM, HuBiogel (a natural growth factor–free, non-denatured extracellular matrix derived from human amnions that can be used to generate microtumors), was neutralized to a pH of 7.0 and mixed with FBS prior to the addition of cells at a concentration of 5000 cells per 10 µL HuBiogel/FBS. The final solution was pipetted as beads onto a custom proprietary tool using an automated multichannel pipette for uniformity, with

n = 4 replicates per condition. The beads were incubated for 20–22 min to ensure gelation before being transferred to 96-well plates containing PTES medium. Microtumors were transferred to opaque flat-bottom plates (Cat #) for CellTiter-Glo assays and clear round-bottom, black-walled plates (Cat #) for imaging by calcein-AM. Once established, the organoids were characterized for viability, morphology, and expression of epithelial markers (e.g., E-cadherin and CK7) using immunofluorescence staining. The schedule is seen in

Figure 2.

2.4. Drug Treatment

Drug concentrations for microtumor treatment were calculated based on clinical doses reported using the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) guidelines for in vitro dosing. Each treatment was reconstituted in either 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma #D2650-5X5ML, Cream Ridge, NJ, USA) or molecular biology grade water (Corning #46-000-CI) and frozen at −80 °C as aliquots at 10 mM (carboplatin) or 20 mM (paclitaxel and docetaxel). On day 4 of the assay, aliquots were thawed at room temperature for an hour prior to dilution to Dose 1 in the appropriate solvent (

Table 1). Two additional doses were added, resulting in Dose 1 as 1:10, Dose 2 as 1:100, and Dose 3 as 1:1000 of the clinical in vitro dose. Treatments were applied to microtumors as 3 combinations—carboplatin and paclitaxel, carboplatin and docetaxel, and carboplatin and PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin. Solvent controls were included in this study to confirm that the effects on microtumor viability were due to treatment and to observe total microtumor growth over the 7 days. SKOV-3 was treated with carboplatin only as a positive control.

2.5. CellTiter-Glo 3D

The CellTiter-Glo 3D Cell Viability Assay (Promega #G9683, Madison, WI, USA) was used on days 1, 4, and 7 for each tumor to assess treatment effects. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and luminescence was measured on a BioTek Cytation 5 (

Figure 3). Drug responses were assessed by measuring maximum growth inhibition (%GImax) after treatment, and Microtumors were classified based on their response to the treatments. The functional efficacy of each treatment regimen was quantified through the measurement of maximum growth inhibition percentage (%GImax) in the PDMs. Based on these %GImax values, the samples were classified into three distinct response categories: full response (>70% GImax), moderate response (30–70% GImax), and no response (<30% GImax). The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1) was also used for clinical imaging assessment, which establishes that a tumor shrinkage of 30% is indicative of a partial response to chemotherapy. However, it was not applied to the PDM growth inhibition readout [

11].

4. Discussion

This feasibility study highlights the potential of PDMs as a valuable tool for advancing research and personalized treatment strategies in EOC. Our cohort of 10 patients demonstrated successful PDM development and effective testing against three specific carboplatin-containing chemotherapy regimens in a timely manner following surgery.

While this was a small sample size, there were 3 PDMs collected from PDS that showed initial organoid responses pan-sensitivity to all administered treatments, highlighting a significant clinical challenge to understand the biological underpinnings of chemo-naïve tumors and predicting their potential resistance and recurrence to future therapies. The field of oncology is moving towards more personalized and tumor-specific treatment, and this pan-responsiveness to multiple therapies does not answer the question of how this tumor will ultimately act at recurrence and what therapy it will respond to.

To tackle this issue, a hypothesis emerges suggesting that applying chemotherapy pressure to these organoids may further elucidate the subsequent treatment response of the tumors in future recurrences. The initial absence of chemotherapy exposure in these organoids leaves a gap in predictability regarding future resistance development, posing the question of how their responses are influenced under chemotherapy conditions. This theory postulates that by administering chemotherapy and subsequently testing the organoids derived from IDS, clinicians may achieve a more accurate reflection of the cancer’s future trajectory and responsiveness to treatment. Moreover, applying chemotherapy pressure could potentially unveil distinct resistance mechanisms that are not observable in chemo-naïve conditions. This dynamic approach—assessing organoid responses to chemotherapy—could yield insights not only into drug efficacy but also into the adaptive changes within tumor biology that occur as a direct consequence of treatment pressure.

PDMs are ex vivo 3D cultures generated directly from freshly resected patient tumor tissue that preserve native architecture, cellular heterogeneity, and key TME components—making them fundamentally different from traditional 2D cell lines, cell-line–derived xenografts (CDX), and even patient-derived xenografts (PDX). Conventional cell lines are typically long-passaged and clonally selected; they lose intratumoral heterogeneity and most stromal/immune context, so treatment responses frequently reflect “cell-autonomous” sensitivity rather than clinically relevant, TME-modulated chemoresistance. CDX models add in vivo growth but start from the same “flattened” cell line biology and are dominated by murine stroma, limiting fidelity to patient tumors. PDX models better conserve many tumor genomic features and heterogeneity than CDX, but over serial passaging, the human stroma and immune elements are largely replaced by mouse counterparts, and experiments are slower/costlier and often require immunodeficient hosts—constraints that blunt the ability to interrogate human immune–tumor interactions and microenvironment-driven resistance mechanisms [

12,

13,

14]. In contrast, PDMs can retain patient-matched extracellular matrix, fibroblasts, myeloid/immune populations, and secreted cytokine/growth-factor programs for a window of time, enabling functional drug testing in a setting where classic chemoresistance drivers—cell–cell contact, hypoxia/nutrient gradients, ECM stiffness, paracrine signaling, and immune-stromal cross-talk—remain operative, which helps explain why PDM platforms can be used to identify patient-specific vulnerabilities and treatment response patterns that are harder to capture with cell lines, CDX, or passaged PDX alone as demonstrated in this feasibility study [

15].

As we can identify tumors that are responders to different therapies by in silico high-throughput testing of microtumors, we may be able to focus on understanding the factors contributing to variability in drug response. By utilizing these PDMs not only for drug testing, but also for observation of biomarker changes pre- and post-IDS, patients may eventually be able to be further stratified into groups that would benefit from specific combination treatments, both established and novel.

At the time of data cutoff, one patient’s recurrences were documented. Patient 7 recurred after carbo/taxol and showed generally low PDM responses across all regimens, consistent with poor clinical outcomes, and no further treatment was planned. This case highlights the potential of PDMs as a tool for real-time therapeutic evaluation and clinical decision-making.

Several limitations should be acknowledged and emphasized. First, this is a small feasibility cohort (n = 10) with an imbalance between PDS (n = 3) and IDS (n = 7); as such, all the findings are descriptive and cannot explicitly predict conclusions. Clinical implications and outcomes are also immature, and no statistically meaningful clinical correlation can be inferred from only one recurrence event. Accordingly, we have not performed any formal statistical comparisons. However, this will be prioritized in future larger cohorts with longer follow-up. Additionally, %GImax was set at a predefined concentration, and we did not present dose–response curves or replicate variability, considering the pilot nature of the study. Histological validation (H&E and immunohistochemistry) was not available for this cohort and will also be incorporated in future studies. Finally, we also acknowledge that the commercial/proprietary limitations (full disclosure of the material composition of HuBiogel) limit the reproducibility of this study.

Future research should focus on increasing the cohort size, exploring a wider range of therapeutic combinations, and delving into the molecular mechanisms that underlie the drug responses observed in patient-derived microtumors. As this technology becomes more integrated into cancer-targeted therapy, there is potential for clinical trial development utilizing microtumor models to assess interval debulking tumor samples, with the potential to change adjuvant treatment regimens and to ultimately enhance patient outcomes and survival rates. Traditionally, the field of gynecologic oncology has been cautious about moving away from platinum-based treatments as first-line chemotherapy in HGSOC patients. However, if microtumor models accurately reflect platinum resistance, there exists a compelling opportunity to intervene earlier and to further develop targeted and personalized treatment strategies tailored to individual patient needs. This shift could significantly improve therapeutic efficacy and foster more effective cancer management.