Changes in Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco Use Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adolescents in Catalonia: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

Highlights

- Binge drinking increased among younger adolescents after COVID-19 restrictions.

- Cannabis and tobacco use declined and remained lower post-pandemic.

- Social environments influenced substance use patterns during and after COVID-19.

- The findings highlight the need for preventive strategies and awareness campaigns.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Variables

2.2.1. Dependent Variables

2.2.2. Independent Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSE | Compulsory Secondary Education |

| PCSE | Post-Compulsory Secondary Education |

| ILTC | Intermediate-Level Training Cycles |

| aPR | Adjusted Prevalence Ratios |

References

- Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas. Encuesta Sobre Uso De Drogas En Enseñanzas Secundarias En España (ESTUDES), 1994–2023; Ministerio de Sanidad. Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health and Treatment of Substance Use Disorders; World Health Organization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Teixidó-Compañó, E.; Sureda, X.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Villalbí, J.R.; Puigcorbé, S.; Colillas-Malet, E.; Franco, M.; Espelt, A. Understanding How Alcohol Environment Influences Youth Drinking: A Concept Mapping Study among University Students. Adicciones 2023, 35, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, M.; Legrand, L.N.; Iacono, W.G.; McGue, M. Parental Smoking and Adolescent Problem Behavior: An Adoption Study of General and Specific Effects. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 1338–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto-Ley 30/2021, de 23 de Diciembre, por el que se Adoptan Medidas Urgentes de Prevención y Contención Para Hacer Frente a la Crisis Sanitaria Ocasionada por la COVID-19; Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2021.

- Bacigalupe, A.; Martín, U.; Franco, M.; Borrell, C. Desigualdades Socioeconómicas y COVID-19 En España. Informe SESPAS 2022. Gac. Sanit. 2022, 36, S13–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogés, J.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Colom, J.; Folch, C.; Barón-Garcia, T.; González-Casals, H.; Fernández, E.; Espelt, A. Consumption of Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco in a Cohort of Adolescents before and during COVID-19 Confinement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, J.R.; Baumler, E.; Wood, L.; Guillot-Wright, S.; Torres, E.; Thiel, M. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Adolescent Mental Health and Substance Use. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 71, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorisdottir, I.E.; Asgeirsdottir, B.B.; Kristjansson, A.L.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Jonsdottir Tolgyes, E.M.; Sigfusson, J.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Halldorsdottir, T. Depressive Symptoms, Mental Wellbeing, and Substance Use among Adolescents before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Iceland: A Longitudinal, Population-Based Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, K.; Merrill, J.; Stevens, A.; Hayes, K.; White, H. Changes in Alcohol Use and Drinking Context Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multimethod Study of College Student Drinkers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 45, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Límites de Consumo de Bajo Riesgo de Alcohol. Actualización del riesgo relacionado con los niveles de consumo de alcohol, el patrón de consumo y el tipo de bebida. Parte 1. In Actualización De Los Límites De Consumo De Bajo Riesgo De Alcohol; Ministerio de Sanidad Centro de Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rogés, J.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Folch, C.; Teixidó-Compañó, E.; González-Casals, H.; Colom, J.; Lafon-Guasch, A.; Fortes-Muñoz, P.; Espelt, A. Effects of Social and Environmental Restrictions, and Changes in Alcohol Availability in Adolescents’ Binge Drinking during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knell, G.; Robertson, M.C.; Dooley, E.E.; Burford, K.; Mendez, K.S. Health Behavior Changes During COVID-19 Pandemic and Subsequent “Stay-at-Home” Orders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepis, T.S.; De Nadai, A.S.; Bravo, A.J.; Looby, A.; Villarosa-Hurlocker, M.C.; Earleywine, M. Alcohol Use, Cannabis Use, and Psychopathology Symptoms among College Students before and after COVID-19. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 142, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.; Carmona, A.; Carbonell, X. Motivos para el consumo de tabaco, alcohol y cannabis en el contexto del confinamiento por COVID-19. Alerta 2023, 6, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brime, B.; García, N.; León, L.; Llorens, M.; López, M.; Molina, M.; Tristán, C.; Sánchez, E. Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones. In Alcohol, Tabaco y Drogas Ilegales en España.; Ministerio de Sanidad; Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, H.B.; Chen, C.M.; Yi, H. Early Adolescent Patterns of Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana Polysubstance Use and Young Adult Substance Use Outcomes in a Nationally Representative Sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 136, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, T.M.; Ellis, W.; Litt, D.M. What Does Adolescent Substance Use Look Like During the COVID-19 Pandemic? Examining Changes in Frequency, Social Contexts, and Pandemic-Related Predictors. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogés, J.; González-Casals, H.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Folch, C.; Colom, J.; Casabona, J.; Drou-Roget, G.; Teixidó-Compañó, E.; Fernández, E.; Vives-Cases, C.; et al. Monitoring Health and Health Behaviors among Adolescents in Central Catalonia: DESKcohort Protocol. Gac. Sanit. 2023, 37, 102316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteagudo, M.; Rodriguez-Blanco, T.; Pueyo, M.J.; Zabaleta-del-Olmo, E.; Mercader, M.; García, J.; Pujol, E.; Bolíbar, B. Gender Differences in Negative Mood States in Secondary School Students: Health Survey in Catalonia (Spain). Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vázquez Fernández, M.E.; Muñoz Moreno, M.F.; Fierro Urturi, A.; Alfaro González, M.; Rodríguez Molinero, L.; Bustamante Marcos, P. Estado de ánimo de los adolescentes y su relación con conductas de riesgo y otras variables. Rev. Pediatr. Aten. Primaria. 2013, 15, e75–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.J.D.; Hirakata, V.N. Alternatives for Logistic Regression in Cross-Sectional Studies: An Empirical Comparison of Models That Directly Estimate the Prevalence Ratio. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2003, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.L.; Myers, J.E.; Kriebel, D. Prevalence Odds Ratio or Prevalence Ratio in the Analysis of Cross Sectional Data: What Is to Be Done? Occup. Environ. Med. 1998, 55, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelt, A.; Mari-Dell’Olmo, M.; Penelo, E.; Bosque-Prous, M. Applied Prevalence Ratio Estimation with Different Regression Models: An Example from a Cross-National Study on Substance Use Research. Adicciones 2017, 29, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H.; Valentin, D.; Franco-Luesma, E.; Ramaroson Rakotosamimanana, V.; Gomez-Corona, C.; Saldaña, E.; Sáenz-Navajas, M.-P. How Has COVID-19, Lockdown and Social Distancing Changed Alcohol Drinking Patterns? A Cross-Cultural Perspective between Britons and Spaniards. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 95, 104344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miech, R.; Patrick, M.E.; Keyes, K.; O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L. Adolescent Drug Use before and during U.S. National COVID-19 Social Distancing Policies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 226, 108822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorens, N.; Brime, B.; Molina, M. Impacto COVID-19 En El Consumo de Sustancias y Comportamientos Con Potencial Adictivo: Encuesta Del Observatorio Español de Las Drogas y Adicciones. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2021, 95, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche, E.; Gabhainn, S.N.; Roberts, C.; Windlin, B.; Vieno, A.; Bendtsen, P.; Hublet, A.; Tynjälä, J.; Välimaa, R.; Dankulincová, Z.; et al. Drinking Motives and Links to Alcohol Use in 13 European Countries. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2014, 75, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussong, A.M.; Jones, D.J.; Stein, G.L.; Baucom, D.H.; Boeding, S. An Internalizing Pathway to Alcohol Use and Disorder. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2011, 25, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, M.; Raninen, J.; Pennay, A.; Callinan, S. The Relationship between Age at First Drink and Later Risk Behaviours during a Period of Youth Drinking Decline. Addiction 2023, 118, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, M.; Fisher, J.C.; Moody, J.; Feinberg, M.E. Different Kinds of Lonely: Dimensions of Isolation and Substance Use in Adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1755–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clendennen, S.L.; Case, K.R.; Sumbe, A.; Mantey, D.S.; Mason, E.J.; Harrell, M.B. Stress, Dependence, and COVID-19–Related Changes in Past 30-Day Marijuana, Electronic Cigarette, and Cigarette Use among Youth and Young Adults. Tob. Use Insights 2021, 14, 1179173X211067439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, J.E.; Stevens, A.K.; Jackson, K.M.; White, H.R. Changes in Cannabis Consumption Among College Students During COVID-19. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2022, 83, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella Juan, L.; Marcos-Delgado, A.; Fernández-Suárez, N.; Molina-de la Torre, A.J.; Fernández-Villa, T. Impacto de La Pandemia Por La COVID-19 En El Consumo de Cannabis En Jóvenes y Población General: Una Revisión Sistemática. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2021, 97, e202312106. [Google Scholar]

- UNODC. COVID-19 y la Cadena de Suministro de Drogas: De la Producción y el Tráfico al Consumo; Oficina de las Naciones Unidas Contra la Droga y el Delito: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hviid, S.; Pisinger, V.; Hoffman, S.H.; Rosing, J.; Tolstrup, J. Alcohol Use among Adolescents during the First Pandemic Lockdown in Denmark, May 2020. Scand. J. Public Health 2023, 51, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Impact of COVID-19 on Patterns of Drug Use and Drug-Related Harms in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs, J.L. Adolescent Life in the Early Days of the Pandemic: Less and More Substance Use. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelham, W.E.; Tapert, S.F.; Gonzalez, M.R.; McCabe, C.J.; Lisdahl, K.M.; Alzueta, E.; Baker, F.C.; Breslin, F.J.; Dick, A.S.; Dowling, G.J.; et al. Early Adolescent Substance Use Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Survey in the ABCD Study Cohort. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, H.E.R.; Song, A.V.; Halpern-Felsher, B.L. Earlier Age of Smoking Initiation May Not Predict Heavier Cigarette Consumption in Later Adolescence. Prev. Sci. 2011, 12, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoletto, V.; Cognigni, M.; Occhipinti, A.A.; Abbracciavento, G.; Carrozzi, M.; Barbi, E.; Cozzi, G. Rebound of Severe Alcoholic Intoxications in Adolescents and Young Adults After COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engs, R.; Hanson, D. Gender Differences in Drinking Patterns and Problems among College Students: A Review of the Literature. J. Alcohol Drug Educ. 1990, 35, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Legleye, S.; Piontek, D.; Kraus, L. Psychometric Properties of the Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST) in a French Sample of Adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 113, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumback, T.; Thompson, W.; Cummins, K.; Brown, S.; Tapert, S. Psychosocial Predictors of Substance Use in Adolescents and Young Adults: Longitudinal Risk and Protective Factors. Addict. Behav. 2021, 121, 106985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Period of Time * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID-19 (2019/20) | Post-COVID-19, With Restrictions (2021) | Post-COVID-19, Without Restrictions (2022) | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p-value | |

| Total | 4.641 (42.1) | 3.478 (31.6) | 2.900 (26.3) | |

| Sex | 0.002 | |||

| Boys | 2.209 (47.6) | 1.624 (46.7) | 1.475 (50.9) | |

| Girls | 2.432 (52.4) | 1.854 (53.3) | 1.425 (49.1) | |

| Academic year | <0.001 | |||

| 4th CSE | 2.690 (58.0) | 2.061 (59.3) | 1.463 (50.4) | |

| 2nd PCSE/ILTC | 1.951 (42.0) | 1.417 (40.7) | 1.437 (49.6) | |

| Municipality size ** | <0.001 | |||

| Rural | 2.459 (54.7) | 1902 (56.3) | 1.325 (47.0) | |

| Urban | 2.038 (45.3) | 1476 (43.7) | 1.493 (53.0) | |

| Socioeconomic Position *** | 0.534 | |||

| Disadvantaged | 1.705 (36.8) | 1.238 (35.6) | 1.090 (37.6) | |

| Medium | 1.561 (33.6) | 1.178 (33.9) | 969 (33.4) | |

| Advantaged | 1.375 (29.6) | 1.062 (30.5) | 841 (29.0) | |

| Weekly money | <0.001 | |||

| 0 EUR | 680 (14.7) | 677 (19.5) | 508 (17.5) | |

| 0 EUR–10 EUR | 1.968 (42.4) | 1.345 (38.7) | 1.023 (35.3) | |

| 10.01 EUR–30 EUR | 1.417 (30.5) | 1.045 (30.0) | 919 (31.7) | |

| More than 30 EUR | 576 (12.4) | 411 (11.8) | 450 (15.5) | |

| Mood | <0.001 | |||

| Good mood | 3.571 (76.9) | 2.305 (66.3) | 1.910 (65.9) | |

| Low mood | 1.070 (23.1) | 1.173 (33.7) | 990 (34.1) | |

| Monthly binge drinking | <0.001 | |||

| No | 4.155 (89.5) | 3.068 (88.2) | 2.493 (86.0) | |

| Yes | 486 (10.5) | 410 (11.8) | 407 (14.0) | |

| Cannabis use in the last 30 days | <0.001 | |||

| No | 4.067 (87.6) | 3.202 (92.1) | 2.642 (91.1) | |

| Yes | 574 (12.4) | 276 (7.9) | 258 (8.9) | |

| Daily smoking tobacco | 0.001 | |||

| No | 4.136 (89.1) | 3.180 (91.4) | 2.585 (89.1) | |

| Yes | 505 (10.9) | 298 (8.6) | 315 (10.9) | |

| 4th Year of CSE | 2nd Year of PCSE/ILTC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID-19 (2019/2020) | Post-COVID-19, with Restrictions (2021) | Post-COVID-19, Without Restrictions (2022) | Pre-COVID-19 2019/2020 | Post-COVID-19, with Restrictions (2021) | Post-COVID-19, Without Restrictions (2022) | |

| Boys | PR | aPR * | aPR | PR | aPR | aPR |

| Binge drinking | ||||||

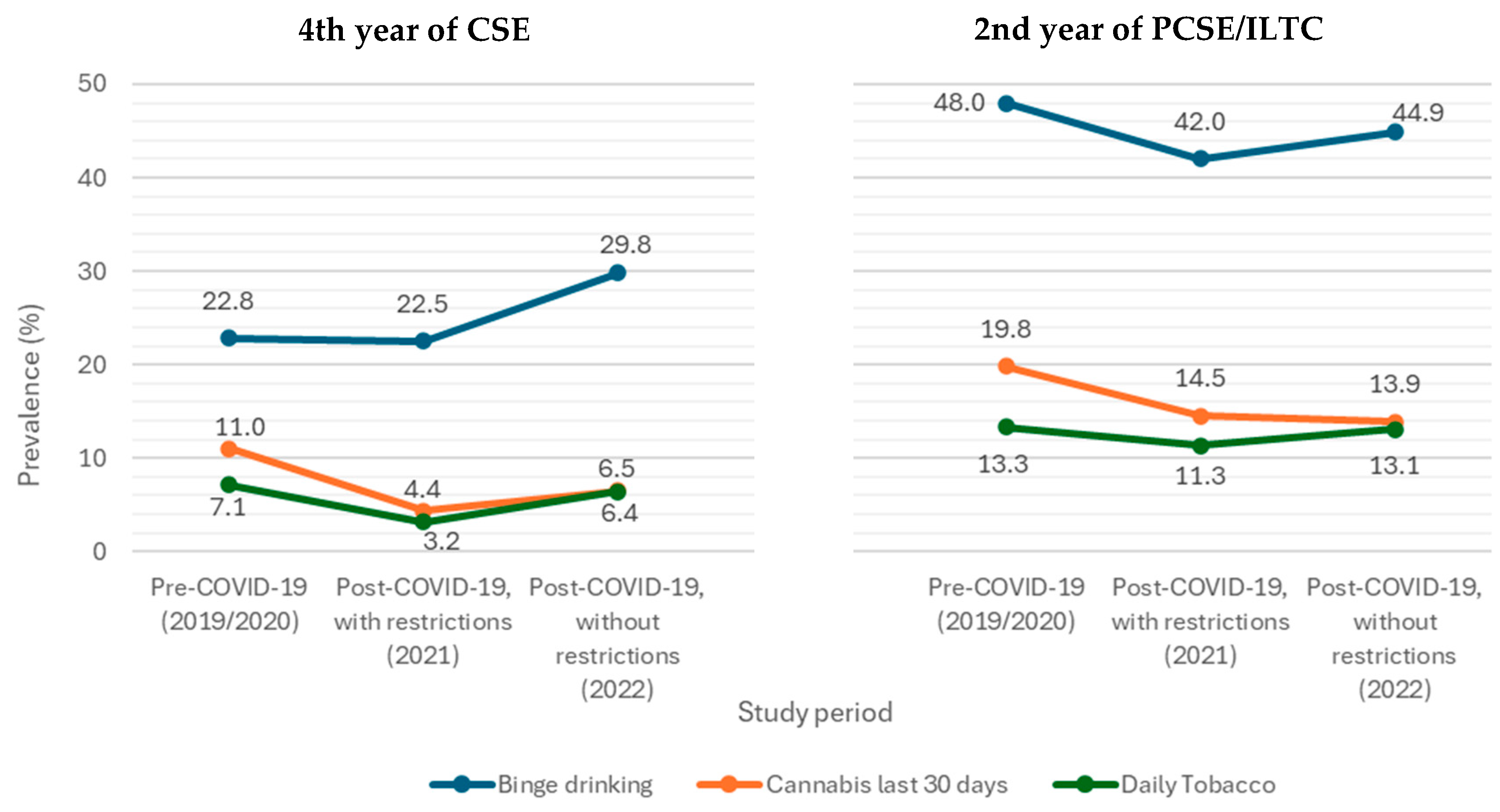

| Prevalence (%) | 22.8 [20.6–25.1] | 22.5 [20.0–25.2] | 29.8 [26.6–33.2] | 48.0 [44.8–51.3] | 42.0 [38.2–45.9] | 44.9 [41.3–48.5] |

| Prevalence Ratio | 1 | 1.0 [0.8–1.4] | 1.7 [1.3–2.3] | 1 | 1.0 [0.8–1.3] | 1.0 [0.8–1.2] |

| Cannabis last 30 days | ||||||

| Prevalence (%) | 11.0 [9.4–12.8] | 4.4 [3.3–5.9] | 6.5 [4.9–8.5] | 19.8 [17.3–22.6] | 14.5 [11.9–17.5] | 13.9 [11.5–16.6] |

| Prevalence Ratio | 1 | 0.4 [0.3–0.6] | 0.6 [0.4–0.8] | 1 | 0.8 [0.6–1.0] | 0.6 [0.5–0.8] |

| Daily Tobacco | ||||||

| Prevalence (%) | 7.1 [5.8–8.6] | 3.2 [2.3–4.5] | 6.4 [4.8–8.3] | 13.3 [11.2–15.7] | 11.3 [9.1–14.0] | 13.1 [10.8–15.7] |

| Prevalence Ratio | 1 | 0.5 [0.3–0.7] | 1.0 [0.7–1.5] | 1 | 0.8 [0.6–1.1] | 0.8 [0.6–1.1] |

| Girls | PR | aPR | aPR | PR | aPR | aPR |

| Binge drinking | ||||||

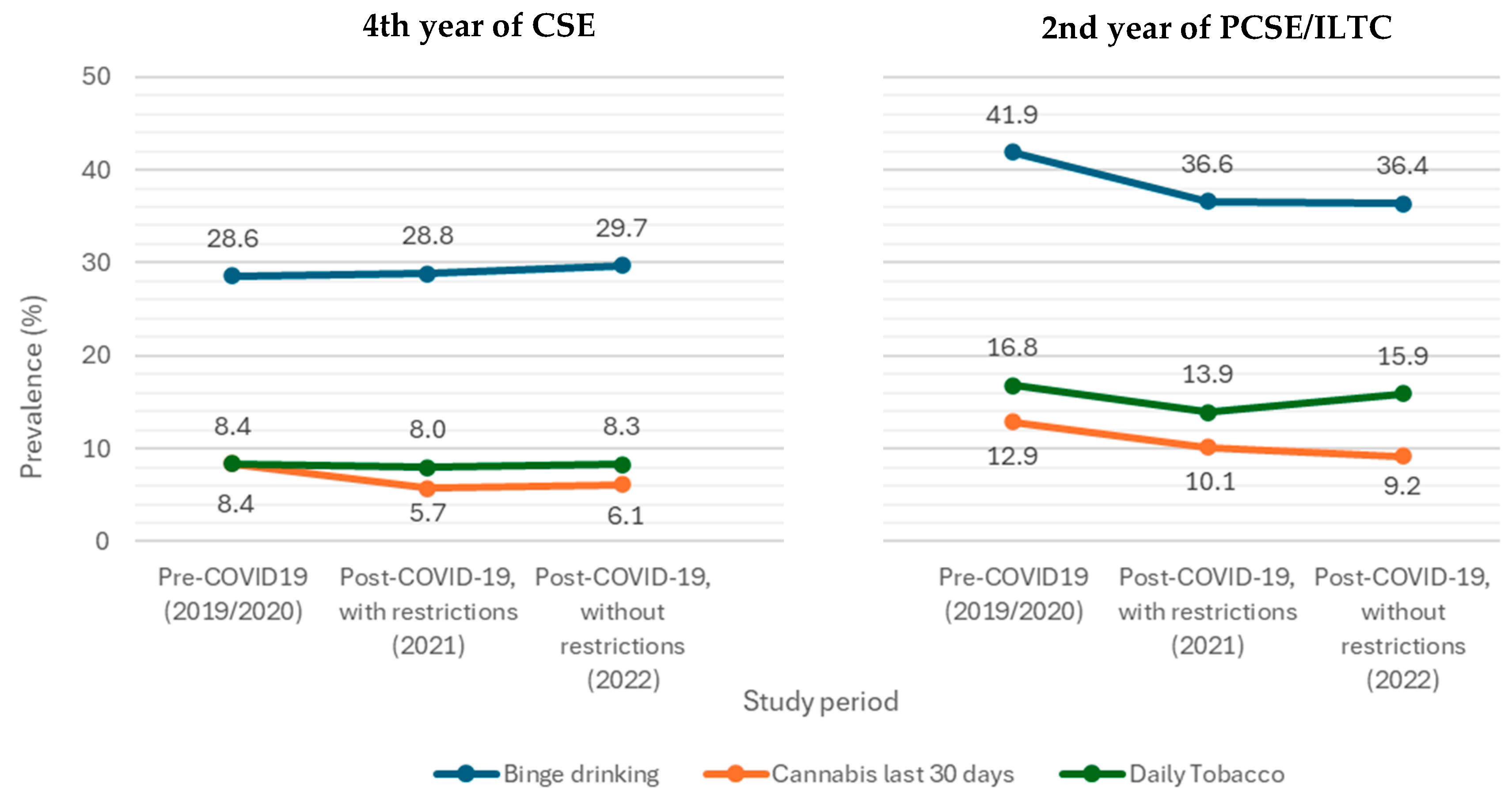

| Prevalence (%) | 28.6 [26.3–31.1] | 28.8 [26.2–31.6] | 29.7 [26.4–33.1] | 41.9 [39.0–45.0] | 36.6 [33.3–40.1] | 36.4 [33.0–40.0] |

| Prevalence Ratio | 1 | 1.5 [1.2–2.0] | 1.5 [1.1–2.1] | 1 | 0.8 [0.6–1.0] | 1.0 [0.7–1.2] |

| Cannabis last 30 days | ||||||

| Prevalence (%) | 8.4 [7.1–10.0] | 5.7 [4.5–7.3] | 6.1 [4.5–8.1] | 12.9 [11.0–15.0] | 10.1 [8.2–12.4] | 9.2 [7.3–11.5] |

| Prevalence Ratio | 1 | 0.6 [0.5–0.8] | 0.6 [0.4–0.8] | 1 | 0.7 [0.6–0.9] | 0.6 [0.4–0.8] |

| Daily Tobacco | ||||||

| Prevalence (%) | 8.4 [7.0–10.0] | 8.0 [6.5–9.8] | 8.3 [6.5–10.6] | 16.8 [14.7–19.2] | 13.9 [11.7–16.5] | 15.9 [13.4–18.8] |

| Prevalence Ratio | 1 | 0.8 [0.6–1.1] | 0.9 [0.6–1.2] | 1 | 0.7 [0.6–0.9] | 0.8 [0.6–1.0] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogés, J.; Pérez, K.; Continente, X.; Guerras, J.M.; Robles, B.; Mateo, I.; Vives-Cases, C.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Gonzalez-Casals, H.; Folch, C.; et al. Changes in Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco Use Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adolescents in Catalonia: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Future 2025, 3, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3030015

Rogés J, Pérez K, Continente X, Guerras JM, Robles B, Mateo I, Vives-Cases C, Bosque-Prous M, Gonzalez-Casals H, Folch C, et al. Changes in Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco Use Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adolescents in Catalonia: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Future. 2025; 3(3):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3030015

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogés, Judit, Katherine Pérez, Xavier Continente, Juan Miguel Guerras, Brenda Robles, Inmaculada Mateo, Carmen Vives-Cases, Marina Bosque-Prous, Helena Gonzalez-Casals, Cinta Folch, and et al. 2025. "Changes in Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco Use Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adolescents in Catalonia: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study" Future 3, no. 3: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3030015

APA StyleRogés, J., Pérez, K., Continente, X., Guerras, J. M., Robles, B., Mateo, I., Vives-Cases, C., Bosque-Prous, M., Gonzalez-Casals, H., Folch, C., Bartroli, M., López, M. J., Fernández, E., & Espelt, A. (2025). Changes in Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco Use Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adolescents in Catalonia: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Future, 3(3), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3030015