Trends and Inequities in the Burden of Depressive Disorders Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the Western Pacific, 1990–2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Data and Definitions

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Burden of Depressive Disorders Among Adolescents and Young Adults Aged 10–24 Years in the Western Pacific Region in 1990–2021

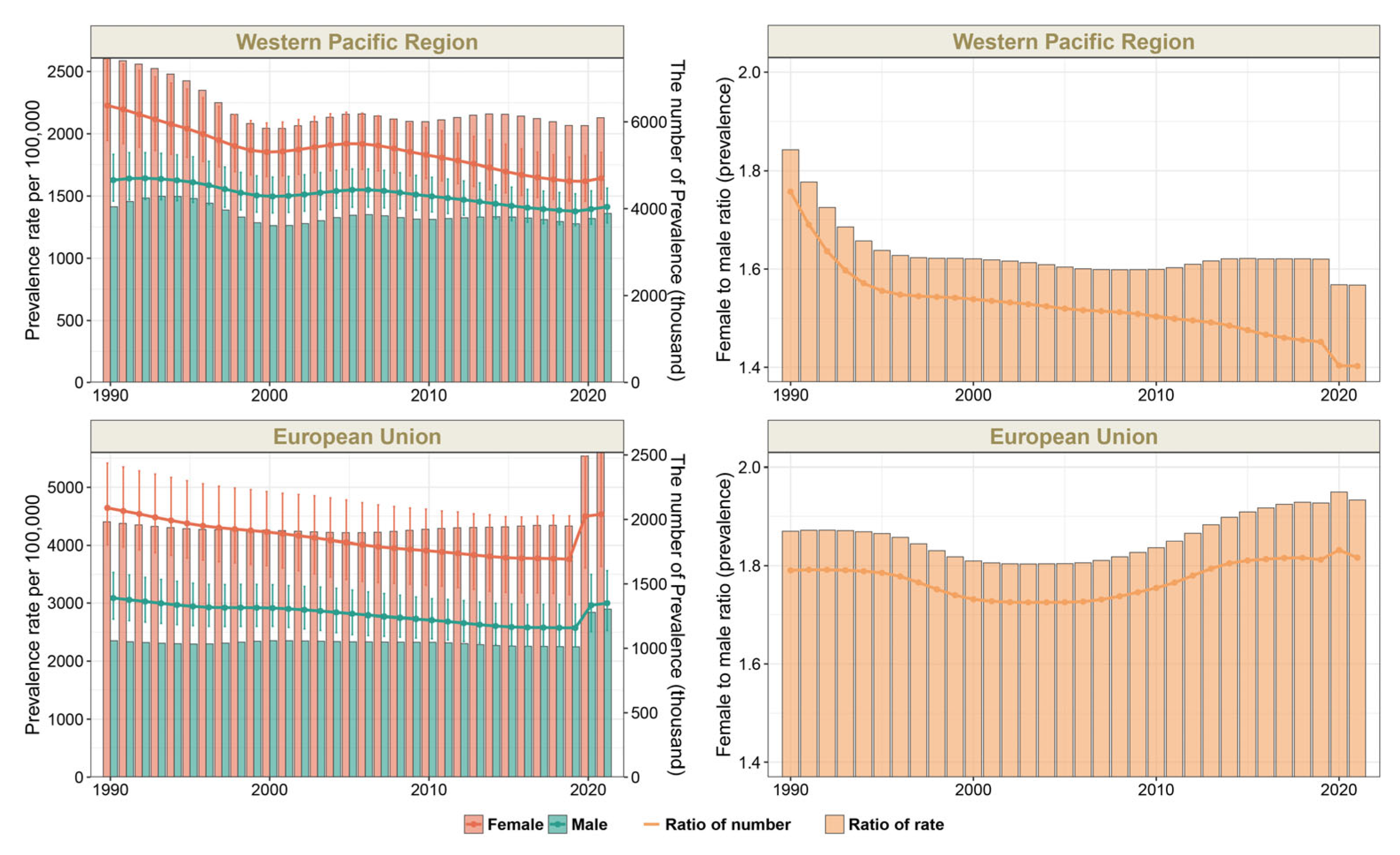

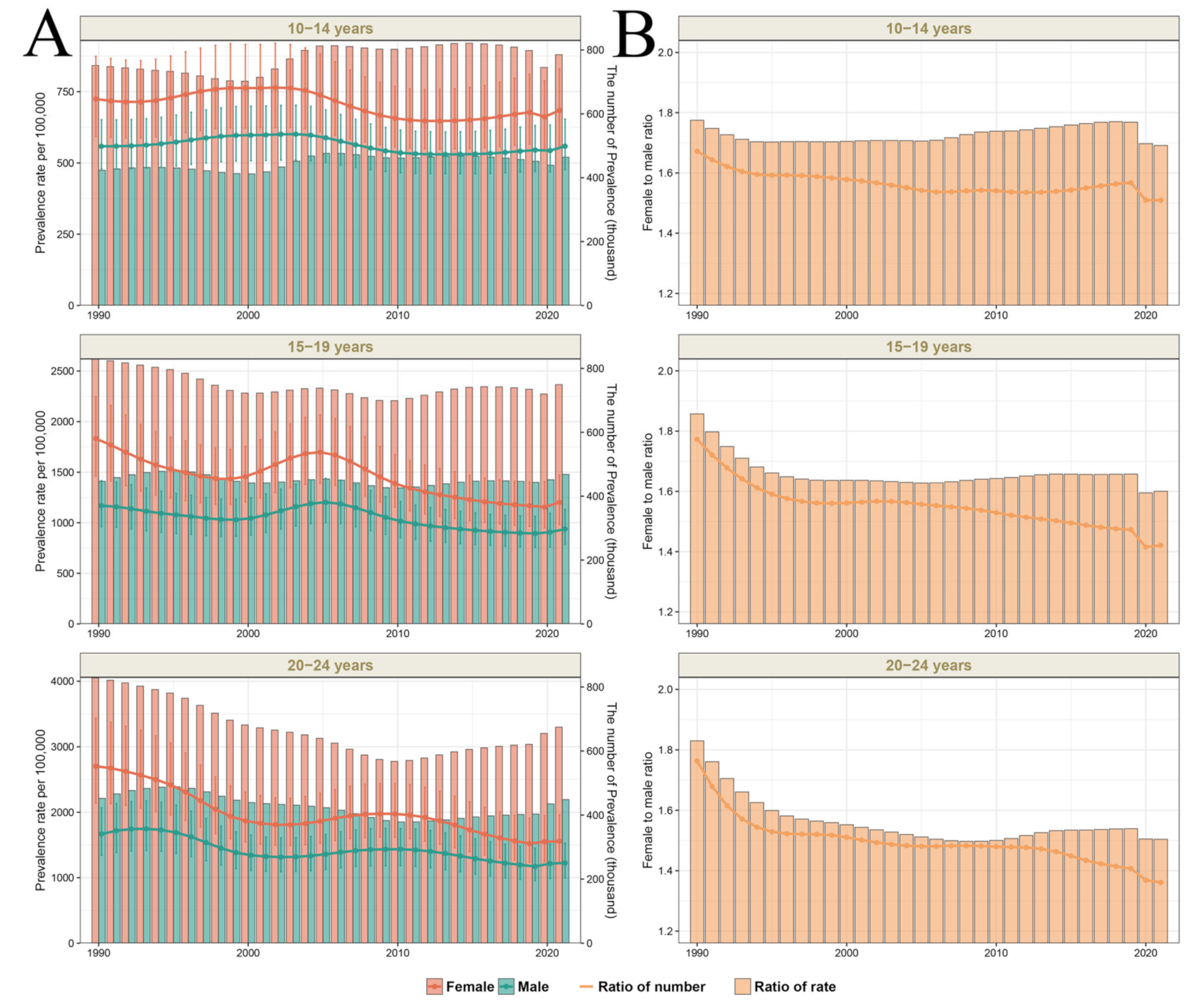

3.2. Sex Differences Among Adolescents and Young Adults Aged 10–24 Years in the Western Pacific Region in 1990–2021

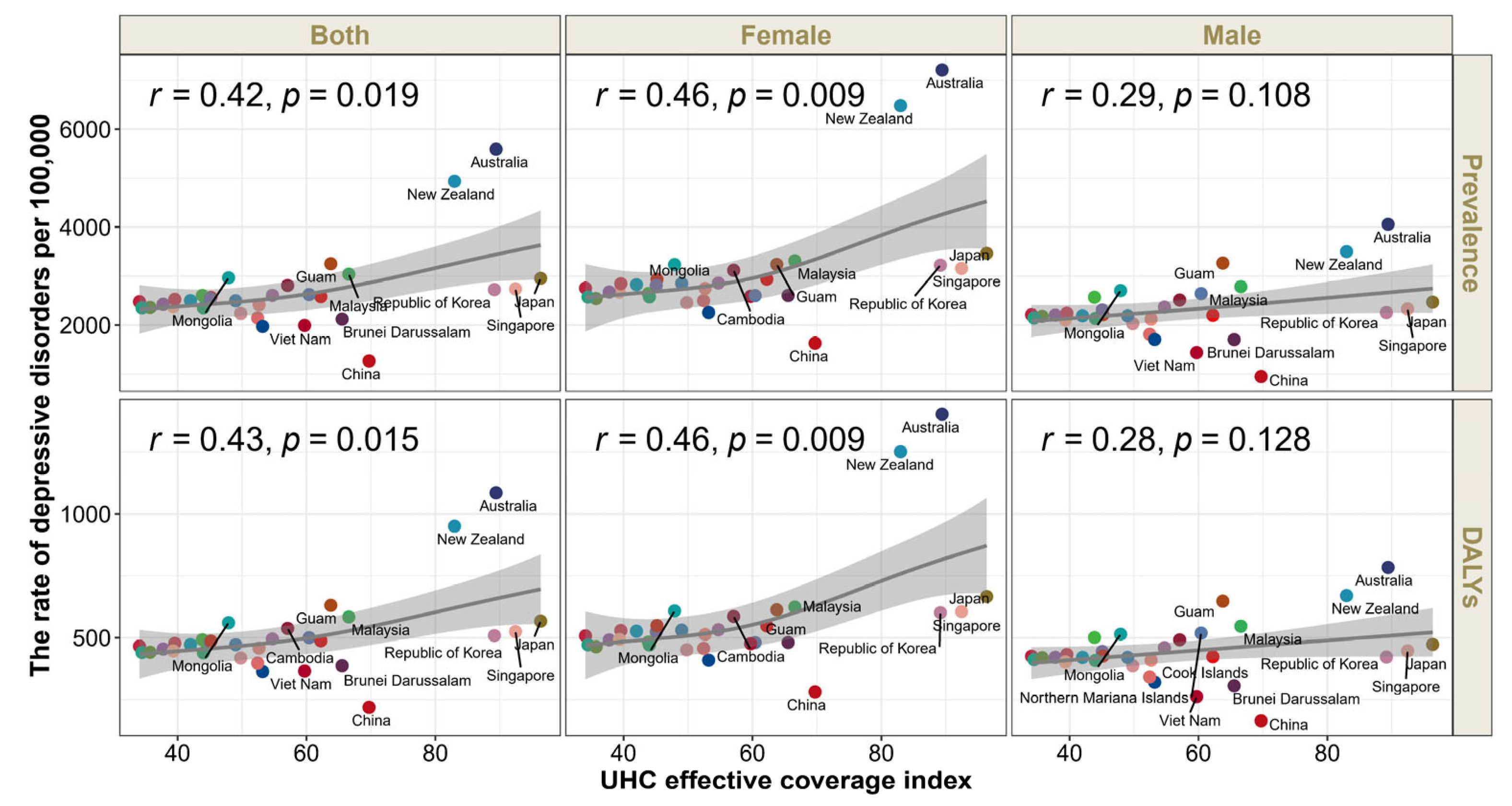

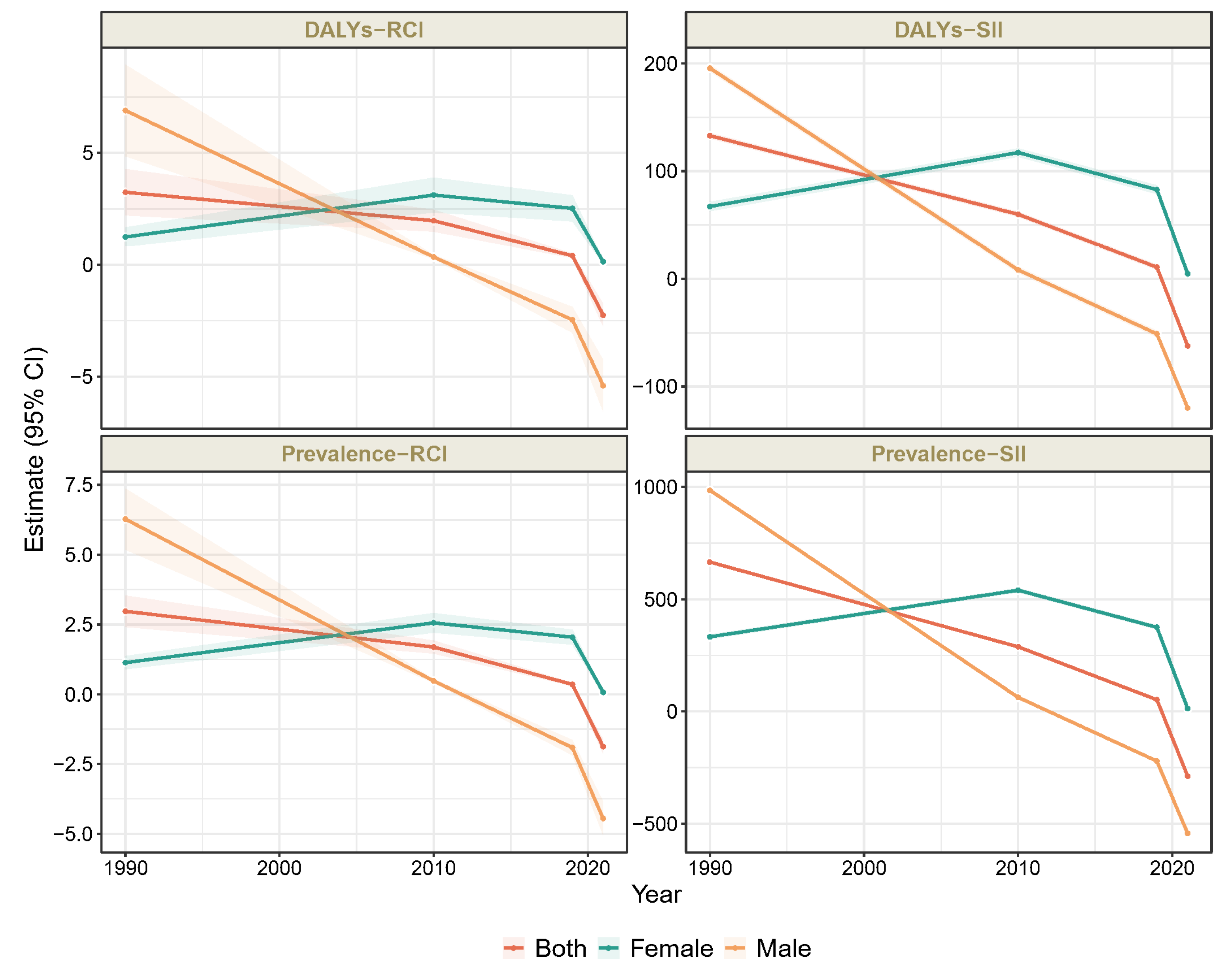

3.3. UHC Effective Coverage-Related Health Inequality in Depressive Disorders Among Adolescents and Young Adults Aged 10–24 Years in the Western Pacific Region

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GBD | Global Burden of Diseases Study |

| UHC | Universal Health Coverage |

| DALYs | Disability-adjusted life years |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| UI | Uncertainty intervals |

| RCI | Relative concentration index |

| SII | Slope of inequality index |

References

- McGrath, J.J.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Altwaijri, Y.; Andrade, L.H.; Bromet, E.J.; Bruffaerts, R.; de Almeida, J.M.C.; Chardoul, S.; Chiu, W.T.; et al. Age of onset and cumulative risk of mental disorders: A cross-national analysis of population surveys from 29 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringaris, A. Editorial: What is depression? J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 1287–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Patel, V.; Saxena, S.; Lund, C.; Thornicroft, G.; Baingana, F.; Bolton, P.; Chisholm, D.; Collins, P.Y.; Cooper, J.L.; Eaton, J.; et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 2018, 392, 1553–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Population Estimates 1950–2019; IHME: Seattle, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelpietra, G.; Knudsen, A.K.S.; Agardh, E.E.; Armocida, B.; Beghi, M.; Iburg, K.M.; Logroscino, G.; Ma, R.; Starace, F.; Steel, N.; et al. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in Europe, 1990-2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 16, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, J.; Huang, Y.; Han, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, X. Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1827–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieling, C.; Buchweitz, C.; Caye, A.; Silvani, J.; Ameis, S.H.; Brunoni, A.R.; Cost, K.T.; Courtney, D.B.; Georgiades, K.; Merikangas, K.R.; et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Disability from Mental Disorders Across Childhood and Adolescence: Evidence from the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.B.; Lv, J.J.; Lu, W.; Yin, M.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Yang, C.H. Burden of depression in adolescents in the Western Pacific Region from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 336, 115889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Universal Health Coverage Collaborators. Measuring universal health coverage based on an index of effective coverage of health services in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1250–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdollahi, M.; Abedi, P.; Abedi, A.; Abolhassani, H.; et al. Five insights from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1135–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishtar, S.; Niinistö, S.; Sirisena, M.; Vázquez, T.; Skvortsova, V.; Rubinstein, A.; Mogae, F.G.; Mattila, P.; Ghazizadeh Hashemi, S.H.; Kariuki, S.; et al. Time to deliver: Report of the WHO Independent High-Level Commission on NCDs. Lancet 2018, 392, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Child Adolescent, H. Universal health coverage and the forgotten generation. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2019, 3, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Handbook on Health Inequality Monitoring with a Special Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, D.A.P.; de Silva, N.; Horton, S.; Patton, G.C.; Schultz, L.; Jamison, D.T. Investment in child and adolescent health and development: Key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd Edition. Lancet 2018, 391, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaxman, A.D.; Vos, D.T.; Murray, C.J. An Integrative Metaregression Framework for Descriptive Epidemiology; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinpoor, A.R.; Nambiar, D.; Schlotheuber, A.; Reidpath, D.; Ross, Z. Health Equity Assessment Toolkit (HEAT): Software for exploring and comparing health inequalities in countries. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guessoum, S.B.; Lachal, J.; Radjack, R.; Carretier, E.; Minassian, S.; Benoit, L.; Moro, M.R. Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Regional Health-Western, P. The widened gap in mental health services during the pandemic. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 15, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M.M.; Klerman, G.L. Sex differences and the epidemiology of depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1977, 34, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faravelli, C.; Alessandra Scarpato, M.; Castellini, G.; Lo Sauro, C. Gender differences in depression and anxiety: The role of age. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 1301–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, C.; Liu, Z.; Gao, L.; Jin, Y.; Shi, J.; Liang, R.; Maimaitiming, M.; Ning, X.; Luo, Y. Global trends and regional differences in the burden of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder attributed to bullying victimisation in 204 countries and territories, 1999-2019: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2022, 31, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salk, R.H.; Hyde, J.S.; Abramson, L.Y. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 783–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Conger, R.D.; Elder, G.H., Jr. Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Dev. Psychol. 2001, 37, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, S.M.; Grabe, S.; Hyde, J.S. Gender, pubertal development, and peer sexual harassment predict objectified body consciousness in early adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 2007, 17, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W.; Shanahan, L.; Miller, S.; Costello, E.J.; Angold, A.; Maughan, B. Outcomes of early pubertal timing in young women: A prospective population-based study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H.; Patel, V.; Kieling, C.; Berk, M.; Buchweitz, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Furukawa, T.A.; Kessler, R.C.; Kohrt, B.A.; Maj, M.; et al. Time for united action on depression: A Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet 2022, 399, 957–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Thornicroft, G.; Knapp, M.; Whiteford, H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007, 370, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Zaki, R.A.; Farid, N.D.N. A systematic review of depression literacy: Knowledge, help-seeking and stigmatising attitudes among adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2019, 74, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermeyer, M.C.; Matschinger, H.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Whom to ask for help in case of a mental disorder? Preferences of the lay public. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1999, 34, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi-Jie, F.; Hong-Mei, G.; Li, W.; Bin-Hong, W.; Yi-Ru, F.; Gang, W.; Tian-Mei, S. Perceptions of stigma and its correlates among patients with major depressive disorder: A multicenter survey from China. Asia Pac. Psychiatry 2017, 9, e12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasahara-Kiritani, M.; Matoba, T.; Kikuzawa, S.; Sakano, J.; Sugiyama, K.; Yamaki, C.; Mochizuki, M.; Yamazaki, Y. Public perceptions toward mental illness in Japan. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2018, 35, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, L.; Li, N.; Srisurapanont, M.; Hong, J.P.; Hatim, A.; Chen, C.H.; Udomratn, P.; Bae, J.N.; et al. Perception of Stigma and Its Associated Factors Among Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A Multicenter Survey from an Asian Population. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, F.Y.; Wilson, L.A.; Veitch, C. Climate adversity and resilience: The voice of rural Australia. Rural. Remote Health 2015, 15, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, C.C.; Li, J.; Mitrou, F.; Zubrick, S.R. Socioeconomic disparities in the mental health of Indigenous children in Western Australia. BMC Public. Health 2012, 12, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1160–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.J.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Patten, S.B.; Freedman, G.; Murray, C.J.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | 1990 | 2019 | 2021 | Percentage Change in Rate * | Percentage Change in Rate # | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number, Thousand | Rate, per 100,000 | Number, Thousand | Rate, per 100,000 | Number, Thousand | Rate, per 100,000 | |||

| Western Pacific region | 9221.77 (7313.66, 11,647.72) | 1994.38 (1581.72, 2519.04) | 5588.20 (4442.00, 6999.32) | 1649.68 (1311.31, 2066.25) | 5841.00 (4607.37, 7338.50) | 1723.14 (1359.21, 2164.91) | −0.14 (−0.18, −0.09) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.08) |

| By sex | ||||||||

| Male | 3344.41 (2630.02, 4209.93) | 1413.27 (1111.39, 1779.02) | 2279.02 (1793.05, 2878.64) | 1275.71 (1003.68, 1611.36) | 2431.20 (1884.65, 3070.31) | 1359.07 (1053.55, 1716.35) | −0.04 (−0.08, 0.01) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.10) |

| Female | 5877.36 (4680.21, 7461.48) | 2603.54 (2073.23, 3305.27) | 3309.18 (2637.56, 4120.41) | 2066.97 (1647.47, 2573.68) | 3409.80 (2704.09, 4274.31) | 2129.95 (1689.13, 2669.97) | −0.18 (−0.23, −0.12) | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.07) |

| Age | ||||||||

| 10–14 years | 896.57 (610.44, 1224.63) | 652.81 (444.48, 891.68) | 815.64 (560.54, 1111.92) | 688.44 (473.13, 938.52) | 843.29 (564.33, 1172.91) | 689.86 (461.65, 959.51) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.05) |

| 15–19 years | 3232.18 (2442.67, 4116.56) | 2000.65 (1511.96, 2548.06) | 1956.81 (1491.28, 2508.93) | 1832.40 (1396.46, 2349.41) | 2062.30 (1557.88, 2698.77) | 1895.75 (1432.07, 2480.82) | −0.05 (−0.11, 0.00) | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.07) |

| 20–24 years | 5093.02 (3901.24, 6604.97) | 3115.17 (2386.21, 4039.96) | 2815.75 (2138.75, 3730.15) | 2481.29 (1884.70, 3287.07) | 2935.40 (2203.58, 3897.72) | 2719.26 (2041.33, 3610.72) | −0.13 (−0.18, −0.08) | 0.10 (0.06, 0.13) |

| By countries and territories | ||||||||

| American Samoa | 0.29 (0.22, 0.38) | 1908.84 (1432.38, 2528.99) | 0.24 (0.18, 0.32) | 1706.87 (1261.42, 2253.41) | 0.27 (0.20, 0.38) | 1971.18 (1407.57, 2729.65) | 0.03 (−0.13, 0.23) | 0.15 (−0.02, 0.37) |

| Australia | 206.67 (159.56, 256.31) | 5205.63 (4019.03, 6456.01) | 236.86 (175.54, 312.74) | 5129.72 (3801.71, 6773.18) | 264.21 (188.71, 357.55) | 5592.03 (3994.14, 7567.77) | 0.07 (−0.14, 0.33) | 0.09 (−0.10, 0.33) |

| Brunei Darussalam | 1.35 (1.01, 1.79) | 1767.78 (1320.09, 2355.71) | 1.97 (1.49, 2.60) | 1822.14 (1375.94, 2408.65) | 2.25 (1.62, 3.15) | 2121.00 (1526.54, 2965.93) | 0.20 (0.01, 0.42) | 0.16 (−0.02, 0.37) |

| Cambodia | 76.26 (56.06, 100.62) | 2378.11 (1747.97, 3137.46) | 100.01 (73.73, 132.15) | 2167.42 (1597.97, 2864.12) | 129.99 (90.19, 181.67) | 2807.48 (1947.84, 3923.47) | 0.18 (−0.02, 0.43) | 0.30 (0.06, 0.55) |

| China | 6967.37 (5532.09, 8874.80) | 1930.24 (1532.61, 2458.68) | 3152.87 (2517.98, 3944.82) | 1347.73 (1076.34, 1686.26) | 2961.49 (2373.05, 3701.06) | 1265.38 (1013.95, 1581.38) | −0.34 (−0.40, −0.29) | −0.06 (−0.10, −0.02) |

| Cook Islands | 0.13 (0.09, 0.18) | 2161.70 (1553.39, 3004.97) | 0.09 (0.07, 0.13) | 2224.75 (1594.59, 3128.94) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.15) | 2579.06 (1734.95, 3775.97) | 0.19 (0.00, 0.44) | 0.16 (−0.03, 0.39) |

| Guam | 1.02 (0.76, 1.35) | 2603.16 (1946.15, 3447.53) | 0.95 (0.71, 1.24) | 2538.01 (1902.02, 3314.02) | 1.17 (0.83, 1.62) | 3251.84 (2296.25, 4497.79) | 0.25 (0.02, 0.49) | 0.28 (0.06, 0.54) |

| Fiji | 4.79 (3.61, 6.31) | 2012.63 (1519.36, 2651.58) | 4.88 (3.59, 6.37) | 2068.47 (1524.67, 2702.83) | 6.14 (4.38, 8.37) | 2563.64 (1831.52, 3498.01) | 0.27 (0.06, 0.54) | 0.24 (0.04, 0.51) |

| Japan | 604.28 (481.35, 755.83) | 2151.67 (1713.94, 2691.26) | 418.32 (333.41, 523.50) | 2348.05 (1871.44, 2938.46) | 518.79 (408.08, 658.20) | 2953.21 (2322.98, 3746.81) | 0.37 (0.29, 0.45) | 0.26 (0.20, 0.33) |

| Kiribati | 0.54 (0.39, 0.71) | 2395.50 (1766.38, 3158.00) | 0.72 (0.53, 0.94) | 2072.14 (1525.84, 2734.78) | 0.83 (0.59, 1.16) | 2359.05 (1661.96, 3293.63) | −0.02 (−0.19, 0.20) | 0.14 (−0.06, 0.39) |

| Laos | 27.54 (20.39, 36.39) | 2134.63 (1580.99, 2821.39) | 46.30 (34.38, 59.96) | 2201.14 (1634.60, 2850.86) | 54.34 (37.55, 76.00) | 2604.00 (1799.43, 3642.39) | 0.22 (−0.01, 0.47) | 0.18 (−0.02, 0.41) |

| Malaysia | 123.26 (89.64, 163.66) | 2294.62 (1668.83, 3046.77) | 299.72 (225.60, 385.64) | 3658.74 (2754.00, 4707.66) | 245.91 (170.51, 344.12) | 3038.94 (2107.14, 4252.58) | 0.32 (0.09, 0.59) | −0.17 (−0.38, 0.06) |

| Marshall Islands | 0.30 (0.22, 0.40) | 1980.59 (1451.19, 2609.81) | 0.34 (0.25, 0.45) | 2024.01 (1488.24, 2702.58) | 0.39 (0.28, 0.54) | 2351.20 (1668.67, 3257.06) | 0.19 (−0.01, 0.44) | 0.16 (−0.04, 0.42) |

| Micronesia | 0.70 (0.51, 0.93) | 2039.32 (1496.30, 2708.73) | 0.65 (0.48, 0.88) | 2040.94 (1493.14, 2730.46) | 0.74 (0.54, 1.02) | 2351.46 (1714.85, 3268.88) | 0.15 (−0.04, 0.40) | 0.15 (−0.04, 0.38) |

| Mongolia | 20.89 (15.38, 27.90) | 2948.45 (2171.30, 3938.48) | 20.95 (15.44, 28.33) | 2892.64 (2132.62, 3913.12) | 22.51 (16.09, 31.36) | 2964.75 (2119.37, 4130.06) | 0.01 (−0.15, 0.19) | 0.02 (−0.14, 0.22) |

| Nauru | 0.06 (0.05, 0.09) | 2125.58 (1537.25, 2936.99) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.10) | 2151.54 (1534.34, 2974.94) | 0.09 (0.06, 0.12) | 2497.47 (1708.65, 3603.45) | 0.17 (−0.03, 0.42) | 0.16 (−0.04, 0.40) |

| New Zealand | 34.76 (26.01, 46.00) | 4132.72 (3092.99, 5469.47) | 48.81 (37.98, 62.77) | 4959.33 (3858.50, 6377.53) | 49.99 (36.63, 67.87) | 4937.38 (3618.19, 6703.87) | 0.19 (0.02, 0.41) | −0.00 (−0.14, 0.16) |

| Niue | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) | 2062.32 (1479.27, 2871.68) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | 2134.41 (1519.22, 2962.34) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | 2495.37 (1690.31, 3581.26) | 0.21 (0.00, 0.46) | 0.17 (−0.03, 0.41) |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 0.27 (0.21, 0.37) | 2150.17 (1629.16, 2899.83) | 0.22 (0.17, 0.29) | 1967.84 (1461.94, 2529.36) | 0.30 (0.21, 0.43) | 2621.54 (1860.90, 3715.52) | 0.22 (−0.01, 0.49) | 0.33 (0.11, 0.62) |

| Palau | 0.10 (0.07, 0.15) | 2226.20 (1591.55, 3128.64) | 0.08 (0.06, 0.11) | 2194.57 (1583.51, 3049.84) | 0.09 (0.06, 0.13) | 2541.35 (1722.38, 3737.45) | 0.14 (−0.06, 0.38) | 0.16 (−0.04, 0.40) |

| Papua New Guinea | 30.99 (22.73, 43.00) | 2366.76 (1735.59, 3283.51) | 66.56 (48.84, 89.71) | 2273.85 (1668.39, 3064.82) | 74.07 (53.06, 104.63) | 2425.48 (1737.53, 3425.98) | 0.02 (−0.15, 0.23) | 0.07 (−0.11, 0.27) |

| Philippines | 438.23 (339.32, 572.56) | 2139.98 (1656.98, 2795.95) | 626.40 (490.20, 816.58) | 1958.46 (1532.61, 2553.05) | 846.82 (653.54, 1119.54) | 2605.90 (2011.11, 3445.14) | 0.22 (0.17, 0.27) | 0.33 (0.27, 0.39) |

| Republic of Korea | 278.32 (224.47, 347.70) | 2117.64 (1707.93, 2645.53) | 195.87 (155.91, 245.53) | 2384.64 (1898.17, 2989.27) | 209.84 (153.97, 281.77) | 2722.35 (1997.51, 3655.53) | 0.29 (0.05, 0.54) | 0.14 (−0.05, 0.36) |

| Samoa | 1.23 (0.90, 1.62) | 2078.05 (1523.70, 2743.78) | 1.19 (0.87, 1.57) | 1938.70 (1426.73, 2565.27) | 1.40 (0.98, 1.95) | 2235.39 (1571.07, 3120.00) | 0.08 (−0.12, 0.28) | 0.15 (−0.05, 0.38) |

| Singapore | 27.64 (22.77, 34.67) | 3351.21 (2761.29, 4204.06) | 18.85 (14.55, 24.17) | 2518.75 (1944.28, 3230.61) | 19.81 (14.72, 26.71) | 2736.48 (2033.14, 3688.46) | −0.18 (−0.34, −0.01) | 0.09 (−0.11, 0.32) |

| Solomon Islands | 2.48 (1.83, 3.29) | 2146.52 (1583.35, 2849.59) | 4.17 (3.07, 5.61) | 2059.14 (1517.55, 2771.81) | 5.01 (3.55, 7.05) | 2376.86 (1684.00, 3347.67) | 0.11 (−0.07, 0.31) | 0.15 (−0.04, 0.38) |

| Tokelau | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | 2106.32 (1517.70, 2922.27) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | 2082.10 (1494.68, 2903.69) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | 2414.63 (1588.30, 3427.80) | 0.15 (−0.05, 0.40) | 0.16 (−0.02, 0.42) |

| Tonga | 0.62 (0.46, 0.81) | 1863.93 (1381.13, 2414.36) | 0.58 (0.43, 0.76) | 1856.25 (1389.61, 2443.55) | 0.67 (0.47, 0.94) | 2144.45 (1521.18, 3019.68) | 0.15 (−0.04, 0.37) | 0.16 (−0.04, 0.38) |

| Tuvalu | 0.05 (0.04, 0.08) | 2196.23 (1582.83, 3070.81) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.10) | 2171.96 (1553.66, 3021.56) | 0.09 (0.06, 0.13) | 2524.22 (1703.77, 3699.38) | 0.15 (−0.03, 0.36) | 0.16 (−0.02, 0.38) |

| Vanuatu | 1.04 (0.76, 1.38) | 2194.70 (1610.88, 2923.64) | 1.93 (1.41, 2.56) | 2141.31 (1563.59, 2836.87) | 2.32 (1.63, 3.25) | 2476.52 (1735.64, 3462.34) | 0.13 (−0.06, 0.36) | 0.16 (−0.04, 0.38) |

| Viet Nam | 372.17 (274.63, 485.56) | 1727.54 (1274.79, 2253.87) | 339.96 (255.73, 436.99) | 1614.67 (1214.61, 2075.51) | 423.10 (294.67, 579.09) | 1992.08 (1387.38, 2726.51) | 0.15 (−0.05, 0.38) | 0.23 (0.03, 0.45) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, J.; Si, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Lian, X.; Xie, S.; Zou, Z.; Li, J. Trends and Inequities in the Burden of Depressive Disorders Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the Western Pacific, 1990–2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 2021. Future 2025, 3, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3020010

Guo J, Si F, Wang H, Wang Y, Lian X, Xie S, Zou Z, Li J. Trends and Inequities in the Burden of Depressive Disorders Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the Western Pacific, 1990–2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 2021. Future. 2025; 3(2):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3020010

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Jianhui, Feifei Si, Huan Wang, Yaqi Wang, Xinyao Lian, Shaodong Xie, Zhiyong Zou, and Jing Li. 2025. "Trends and Inequities in the Burden of Depressive Disorders Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the Western Pacific, 1990–2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 2021" Future 3, no. 2: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3020010

APA StyleGuo, J., Si, F., Wang, H., Wang, Y., Lian, X., Xie, S., Zou, Z., & Li, J. (2025). Trends and Inequities in the Burden of Depressive Disorders Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the Western Pacific, 1990–2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 2021. Future, 3(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3020010