Baseline Knowledge of Peripheral Arterial Disease and Factors Influencing Learning Material Preferences in the San Francisco Chinese-Speaking Community: A Survey Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Surveyed Population Demographics

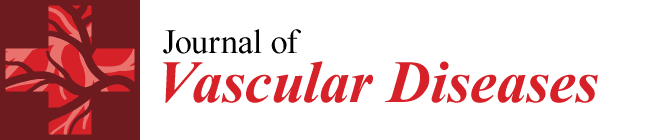

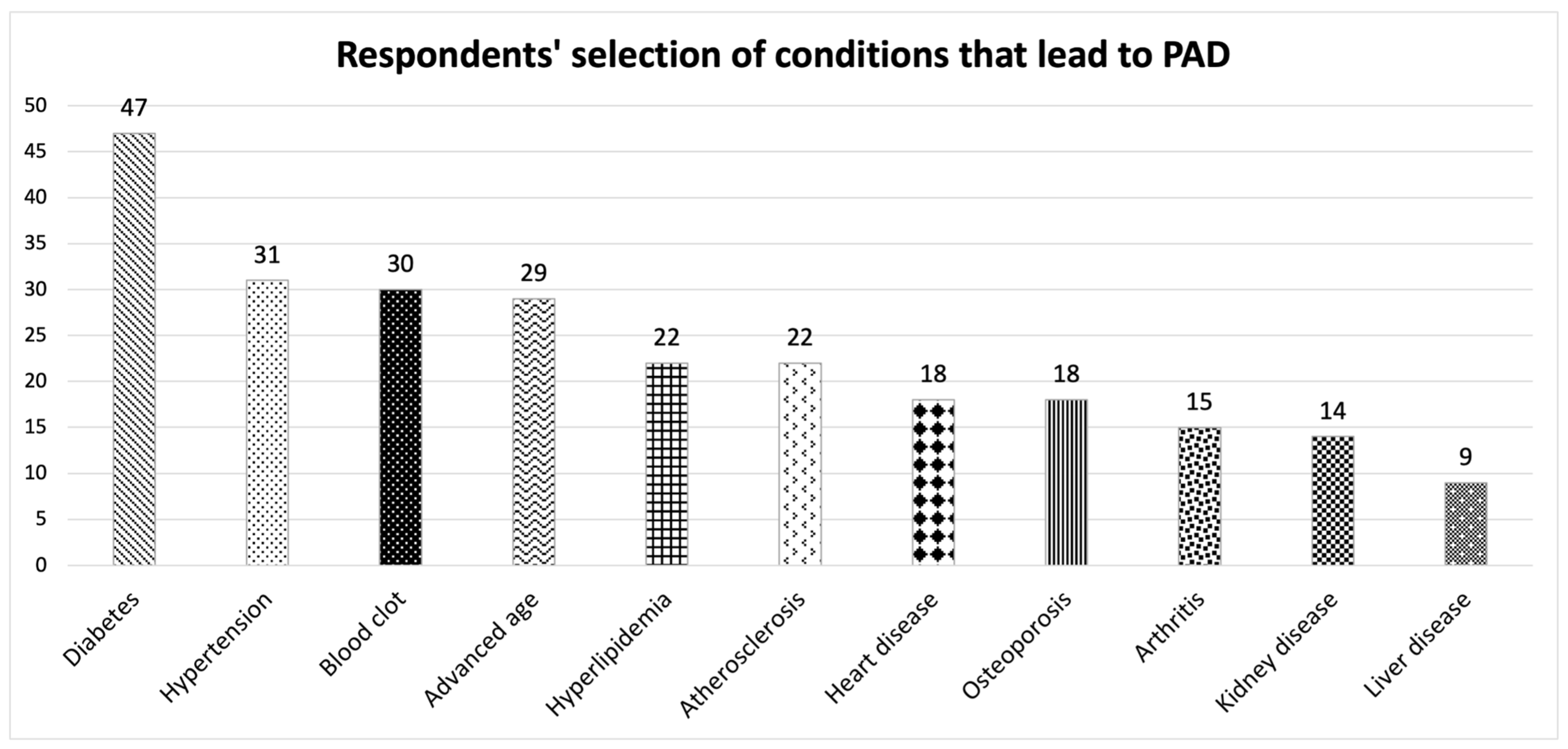

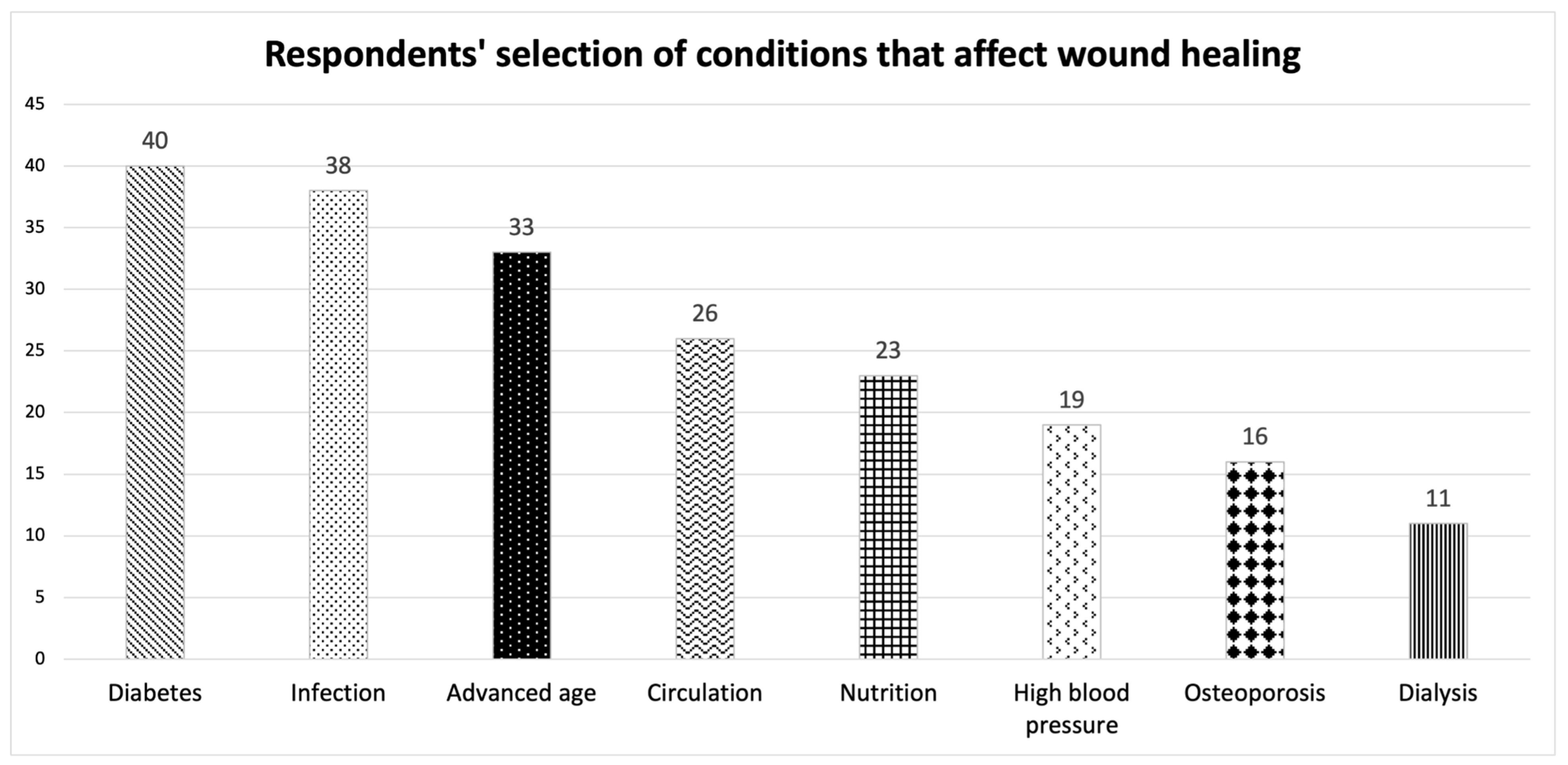

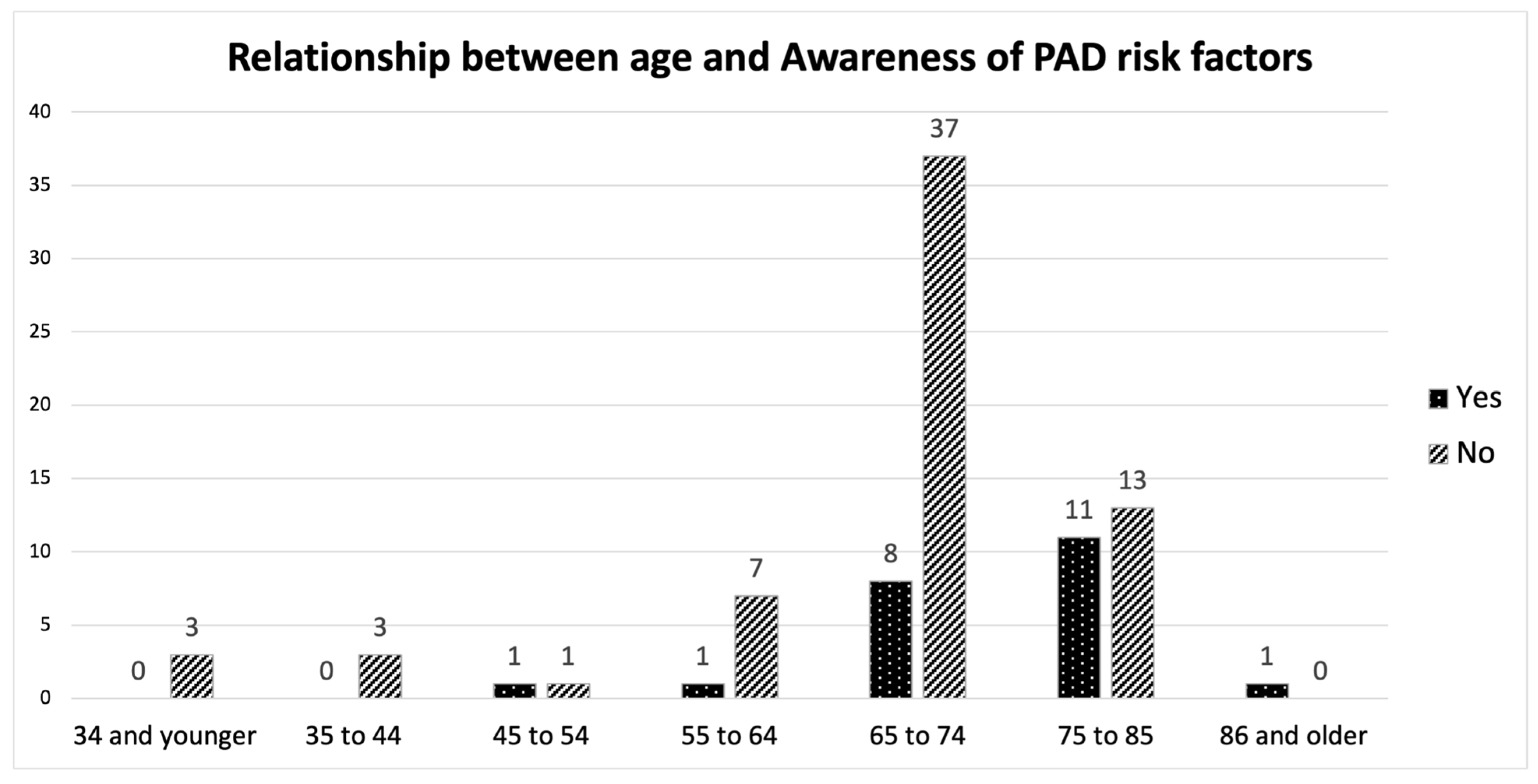

3.2. PAD Baseline Knowledge

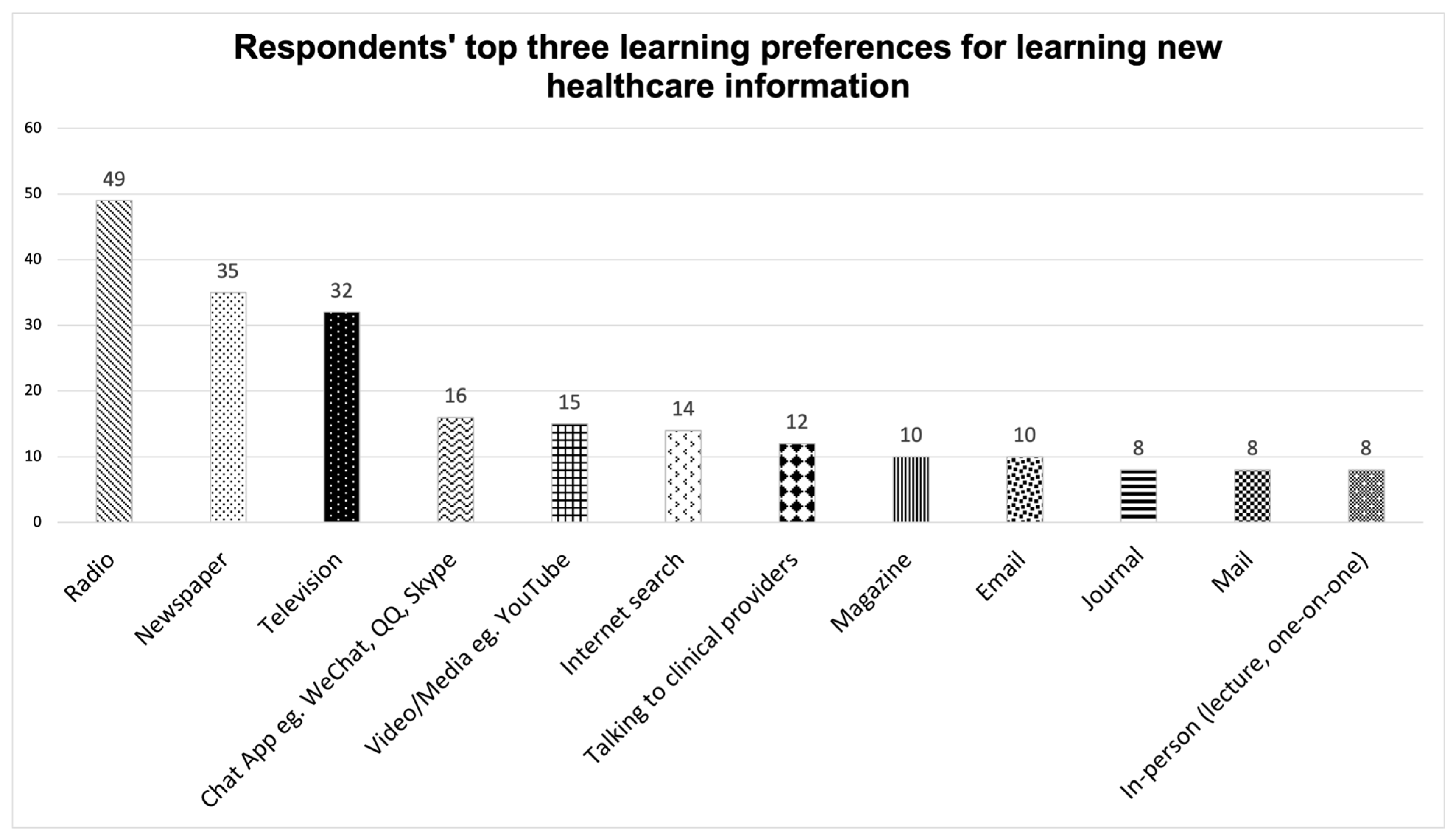

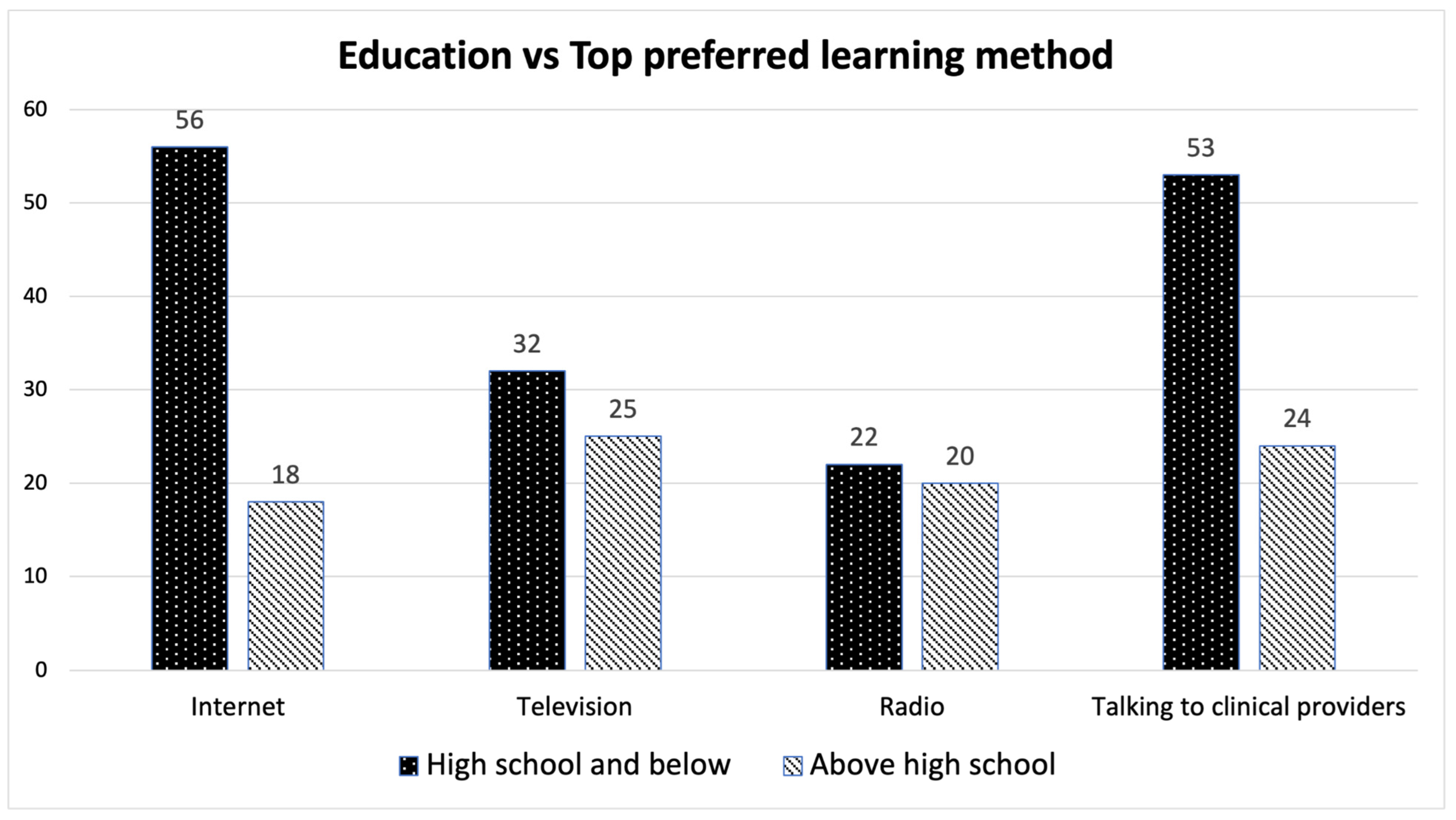

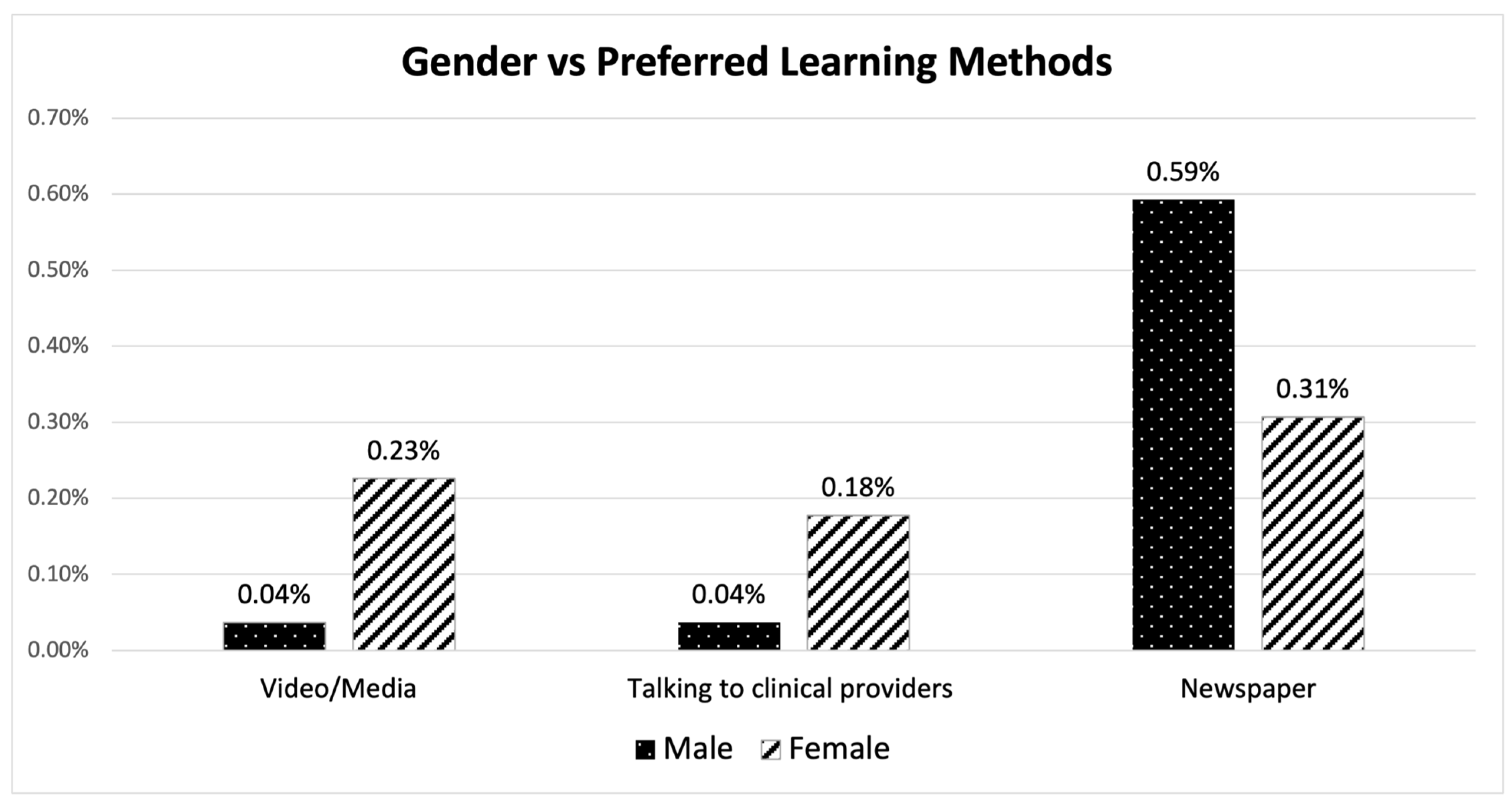

3.3. Inferential Analysis on Age, Gender and Educational Level vs. Preferred Learning Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Age vs. Preferred Learning Methods

4.2. Education Level vs. Preferred Learning Methods

4.3. Gender vs. Preferred Learning Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aday, A.W.; Matsushita, K. Epidemiology of Peripheral Artery Disease and Polyvascular Disease. Circ Res. 2021, 128, 1818–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creager, M.A.; Matsushita, K.; Arya, S.; Beckman, J.A.; Duval, S.; Goodney, P.P.; Gutierrez, J.A.T.; Kaufman, J.A.; Joynt Maddox, K.E.; Pollak, A.W.; et al. Reducing Nontraumatic Lower–Extremity Amputations by 20% by 2030: Time to Get to Our Feet: A Policy Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e875–e891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Members, W.C.; Gornik, H.L.; Aronow, H.D.; Goodney, P.P.; Arya, S.; Brewster, L.P.; Byrd, L.; Chandra, V.; Drachman, D.E.; Eaves, J.M.; et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS guideline for the Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2024, 149, e1313–e1410. [Google Scholar]

- Martelli, E.; Enea, I.; Zamboni, M.; Federici, M.; Bracale, U.M.; Sangiorgi, G.; Martelli, A.R.; Messina, T.; Settembrini, A.M. Focus on the most common paucisymptomatic vasculopathic population, from diagnosis to secondary prevention of complications. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, T.W.; Shih, C.D.; Concha-Moore, K.C.; Diri, M.M.; Hu, B.; Marrero, D.; Zhou, W.; Armstrong, D.G. Disparities in outcomes of patients admitted with diabetic foot infections. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Tan, T.W.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansell, D.A. The Death Gap: How Inequality Kills; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Fair Lending Regulations and Statues Fair Housing Act. 1968. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/supmanual/cch/fair_lend_fhact.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Redlining, H. Social Determinants of Health, and Stroke Prevalence in Communities in New York City. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e235875. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach, S.J.; Thornburg, L.L.; Glantz, J.C.; Hill, E. Associations between historically redlined districts and racial disparities in current obstetric outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2126707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linde, S.; Walker, R.J.; Campbell, J.A.; Egede, L.E. Historic residential redlining and present-day diabetes mortality and years of life lost: The persistence of structural racism. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1772–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Vernon, M.; Hatzigeorgiou, C.; George, V. Health literacy, social determinants of health, and disease prevention and control. J. Environ. Health Sci. 2020, 6, 3061. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33604453 (accessed on 1 October 2024). [PubMed]

- Walters, R.; Leslie, S.J.; Polson, R.; Cusack, T.; Gorely, T. Establishing the efficacy of interventions to improve health literacy and health behaviours: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criqui, M.H.; Matsushita, K.; Aboyans, V.; Hess, C.N.; Hicks, C.W.; Kwan, T.W.; McDermott, M.M.; Misra, S.; Ujueta, F. Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Contemporary Epidemiology, Management Gaps, and Future Directions: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, e171–e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljassim, N.; Ostini, R. Health literacy in rural and urban populations: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2142–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, S.; Heckman, J. Education and Preferences: Experimental Evidences from Chinese Adult Twins. 2010. Available online: http://jenni.uchicago.edu/Spencer_Conference/Papers%202010/Chew_Heckman_Yi_etal_2010_Education%20and%20Preferences.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Snibbe, A.C.; Markus, H.R. You can’t always get what you want: Educational attainment, agency, and choice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 703–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, E.M.; Longo, D.R.; Bardsley, J.K.; Bridges, J.F. Education and patient preferences for treating type 2 diabetes: A stratified discrete-choice experiment. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 1729–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, T.; Tennant, M. Understanding adult learners. In Dimensions of Adult Learning; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Gazal, S.; Kanai, M.; Koch, E.M.; Schoech, A.P.; Siewert, K.M.; Kim, S.S.; Luo, Y.; Amariuta, T.; Huang, H.; et al. Population-specific causal disease effect sizes in functionally important regions impacted by selection. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marantika, J.E.R. Metacognitive ability and autonomous learning strategy in improving learning outcomes. J. Educ. Learn. 2021, 15, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, E.; Zamboni, M.; Sotgiu, G.; Saderi, L.; Federici, M.; Sangiorgi, G.M.; Puci, M.V.; Martelli, A.R.; Messina, T.; Frigatti, P.; et al. Sex-related differences and factors associated with Peri-procedural and 1 year mortality in chronic limb-threatening ischemia patients from the CLIMATE Italian registry. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health 1998, 13, 623–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| May | October | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.759 | ||

| Female | 30 | 34 | |

| Male | 11 | 16 | |

| N/A 1 | |||

| Age (years) | 0 | 3 | |

| under 35 | 0 | 3 | |

| 35 to 44 | 0 | 2 | |

| 45 to 54 | 0 | 5 | |

| 55 to 64 | 24 | 22 | |

| 65 to 74 | 15 | 14 | |

| 86 or above | 1 | 0 | |

| Education 2 | 0.155 | ||

| High school and below | 31 | 29 | |

| Above high school | 10 | 20 | |

| Primary language | N/A 1 | ||

| Cantonese | 38 | 35 | |

| English | 3 | 15 | |

| Mandarin | 5 | 11 | |

| Toishanese | 7 | 7 | |

| Vietnamese | 0 | 3 | |

| Shanghainese | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 0 | 1 | |

| English fluency | N/A 1 | ||

| Extremely well | 0 | 9 | |

| Very well | 2 | 5 | |

| Well | 3 | 6 | |

| Not well | 8 | 7 | |

| Not at all | 29 | 21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shih, C.-D.; Lee, T.; Hassan, S.; Chau, H.; Brooks, B.M.; Zhang, B.; Rosario, E.R. Baseline Knowledge of Peripheral Arterial Disease and Factors Influencing Learning Material Preferences in the San Francisco Chinese-Speaking Community: A Survey Analysis. J. Vasc. Dis. 2025, 4, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jvd4010001

Shih C-D, Lee T, Hassan S, Chau H, Brooks BM, Zhang B, Rosario ER. Baseline Knowledge of Peripheral Arterial Disease and Factors Influencing Learning Material Preferences in the San Francisco Chinese-Speaking Community: A Survey Analysis. Journal of Vascular Diseases. 2025; 4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jvd4010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleShih, Chia-Ding, Tiffany Lee, Sarah Hassan, Hoanganh Chau, Brandon M. Brooks, Benjamin Zhang, and Emily R. Rosario. 2025. "Baseline Knowledge of Peripheral Arterial Disease and Factors Influencing Learning Material Preferences in the San Francisco Chinese-Speaking Community: A Survey Analysis" Journal of Vascular Diseases 4, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jvd4010001

APA StyleShih, C.-D., Lee, T., Hassan, S., Chau, H., Brooks, B. M., Zhang, B., & Rosario, E. R. (2025). Baseline Knowledge of Peripheral Arterial Disease and Factors Influencing Learning Material Preferences in the San Francisco Chinese-Speaking Community: A Survey Analysis. Journal of Vascular Diseases, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jvd4010001