Abstract

Through the pivot to emergency remote teaching during the pandemic, most universities have managed to become ‘digital’, at least in the delivery of educational programmes and business operations. And yet, the purposeful design and use of technology for education is far from the reality of such a pivot and remains difficult to achieve. While most universities outline some level of digital transformation as part of their innovation narrative and strategies, there is only a limited number of universities that adopt the culture of co-creation. This paper illustrates a bottom-up approach to the co-creation of a new digital and medical education strategy in a London-based Russell Group university to bring on change that is fit for purpose. The findings include the key insights, specifically, the five key values of what the community believed to be crucial—(i) broadening access to education, (ii) flexibility, efficiency and convenience, (iii) authentic learning, (iv) business proposition, and (v) pastoral care; and the eight areas of opportunities and challenges—(i) human relationships, (ii) co-creation, (iii) digital engagement, (iv) digital pedagogy, (v) digital literacy, (vi) edtech and IT infrastructure, (vii) support, and (viii) digital assessment and feedback. This paper also outlines the strategic project plans that were generated and since implemented as a result of the co-creation process. The limitations and future directions of this study are also noted.

1. Introduction

The pivot to emergency remote teaching [1] has enabled most universities to become ‘digital universities’ at least from the perspective of the delivery of their educational programmes and business operations. In other words, the business continuity of teaching and learning, through whatever digital technologies needed, was the focus and necessity. However, as the term ‘panic-gogy’ implies [2,3], such a quick transition with very limited time and inadequate educational frameworks only meant that most teachers scrambled to merely translate what they used to do in-person to online ‘delivery’—with long hours of live lectures and uploading PowerPoint slides and PDF files onto Learning Management Systems (LMSs). Those teaching strategies and quick ‘adjustments’ are vastly different from the carefully and purposefully designed learning activities, sequences, and assessments that are conducive for online students and their unique learning experiences. As society gradually settles back into post-pandemic normality, many universities grapple with the questions of ‘What does it mean to be a digital university?’, ‘What lessons have we learned from this unprecedented experience that we want to keep, let go and change for the future?’, and ‘How might we ensure high-quality learning experiences for our students in a post-digital world?’

While there is a plethora of literature on digital learning and learning design, as for what works for effective and engaging online experiences for learners [4,5], the breadth and depth of the literature on how digital learning innovation is conceptualised, strategized, and enacted across the higher education sector is still scarce and requires further studies [6,7]. Further, as the narrative of digital transformation for all aspects of universities becomes even more crucial in the post-pandemic era, there is an exponential pressure to work with and fight against emerging and sophisticated technologies such as Generative AI.

This paper therefore illustrates a case study of a co-creation project in cultivating a culture of innovation and digital education strategy that are fit for purpose and deeply embedded within the institutional and historical contexts, so as to bring on meaningful change for medical and digital education into the future.

2. Methods

Bayne and Gallagher (2021) [8] argue that even within the instrumental narratives of corporate edtech and inevitable digital futures of higher education, “university communities can work to define their own digital futures through an emphasis on collectivity, participation and hope” (p. 607). The body of existing literature also points to the importance of the ‘innovation’ narrative that often resonates with the work of digital transformation within the university sector [6,9].

The intervention described in this paper is inspired by and draws on their theoretical and pragmatic underpinning of the successful project conducted at the University of Edinburgh—to implement the co-design and explorative methods for bringing about carefully crafted change and a digital future for the medical curriculum. The important impact of such participatory processes is that the university community, namely, in this case, medical students, educators, and clinicians, who will go through the change are involved in the process of change from the start.

In 2022, upon reflection on the post-pandemic, post-digital world of medicine, the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, in a London-based Russell Group university appointed a new educational leader, the Dean for Digital Education, to bring about the transformation of medical education and expansion of online programmes within the faculty. This then led to launching the project entitled ‘Discovery towards Strategy: co-creating the digital education strategy’, which ran between September 2022 and April 2023. The project aimed to: (i) make the listening exercise visible by the new leadership to engage and prepare the community that would experience the change; (ii) better understand the current and historical practice, opportunities, and challenges related to digital learning and teaching within the faculty; and (iii) co-create the future strategy in transforming the digital education practice through bottom-up, co-design processes. Figure 1 below describes the timeline and activities that followed as part of this large-scale consultation and co-creation process.

Figure 1.

The project outline (used in the communication as a call to participation).

Building on the appreciative inquiry [10,11] and mixed methods [12], a range of formats for consultation and/or data collection were offered to attract as diverse and large a number of participants and perspectives as possible across the community—namely, medical and dental students (both undergraduates and postgraduates), and academic and professional service staff within the faculty. Over the four months between September and December 2022, the data collection included the formats of: an online survey, interactive drop-in sessions, one-on-one semi-structured interviews, and hybrid workshops (for simultaneous discussion with online and on-campus participants). They were co-facilitated by the faculty’s staff and student partners, along with the author. The key questions that guided the generative discussion and interactive workshops include:

- What values and beliefs do we have about digital education?

- What is working well with digital education within the faculty?

- What is not working so well?

- What could be improved?

With the promotion of the study through various communication channels over the four months, a total of 370 students and staff participated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number and formats of consultations and data collection (The numbers within the grey column ‘Co-lab hybrid workshop’ is inclusive of the third column ‘One-on-one/group/drop-in meetings’ numbers).

2.1. Co-Lab Workshops

The two co-lab workshops (of two hours each) were held for staff and students, respectively, in October 2022. An open invitation to the workshops was sent to the entire staff and student mailing list. A total of eleven university staff and ten students attended the sessions, which were offered via a hybrid mode (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Co-lab sessions with students and staff (October 2022).

2.2. The Digital Education Experience Online Survey

Online surveys on the digital education experience were circulated through multiple communication channels to all faculty staff and students. The survey instruments were co-designed by a student partner who was employed to work on this project with the author. The questionnaire instrument included both open-ended questions for free text responses and likert-scale questions on aspects of the online teaching and learning experience (see Appendix A and Appendix B). The staff survey had 20 questions in total while the student survey included 13 questions. The surveys opened on 18 October and closed on 30 November 2022, using Microsoft Forms. A total of 119 responses (43 staff and 76 students) were returned for analysis. Only the relevant, above-mentioned key questions that generated text responses have been included in the thematic analysis for this study, while other questions on the online survey were used for internal purposes of building connection and future work.

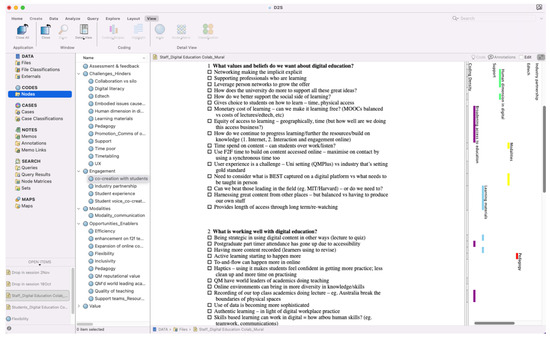

Consequently, the vast range of data, including the text responses of the online surveys and meeting notes, were analysed for content and thematic analysis [13], using nVivo (Figure 3) by the author during September 2022 and January 2023. Open, deductive coding was applied for this analysis to reveal the emerging themes—specifically, a reflexive approach to analysing and synthesising the various data sets was deployed in the study to allow for the interpretive analysis across multiple times of coding [14].

Figure 3.

An example of nVivo coding for thematic analysis.

3. Results

In the following section, the key themes that emerged in relation to staff and students’ values and beliefs about digital education and the opportunities and challenges they faced, are described and discussed. In other words, the results of the data analysis are set out below so as to argue for what should become a core part of the digital education strategy.

3.1. Values and Beliefs

What values and beliefs drive digital education at the faculty and university? Why do we need and care about digital education in the first place? The university’s strategy clearly articulates equity, diversity, and inclusion as core values within the organisation. Digital education, as a way of widening participation and democratising education, resonates strongly with this mission [15]. In exploring why digital education is indeed needed or desired with the faculty, the following five key themes were identified as vital to this mission.

3.1.1. Broadening Access to Education—Inclusion and Accessibility

There was a strong sense of belief that digital education has the power to broaden access to education through technology [16,17,18]. Some staff discussed how lecture attendance increased online in some areas through the pandemic, as students could participate online from anywhere, including from the comfort of their own homes. Asynchronous learning with recorded materials online allowed students to learn anytime and anywhere. These online learning opportunities (both synchronous and asynchronous) were deemed to be inclusive and accessible to many, catering for the diverse needs of learners, although it was noted that they needed to be designed well in order to achieve this [19]. Mixed Mode Education (MME) was often noted as one example of the university’s effort to provide such inclusive education, though in practice, this was felt to be difficult to implement well.

“We are an inclusive university and faculty, with the right infrastructure digital education can only help with this. Increasing the quality and quantity of our digital educational offering for on-site as well as distance learners.”(Staff)

“I have ADHD and as someone with a neurodiversity digital education is more suited to my style of learning. I would have severely struggled with in-person teaching.”(Student)

3.1.2. Flexibility, Efficiency, and Convenience

Building on the diverse needs of the university’s students and staff, digital education was deemed to provide flexibility, efficiency, and convenience. This was considered critical in medical education, which includes students studying a packed curriculum and with clinical placements; and clinicians who work in high-pressure health organisations such as the NHS; and university academics who have competing life priorities across their research, education, and clinical work. Students, in particular, discussed how important it is to have the flexibility of attending lectures online and accessing recorded lectures when/if they are missed. Commuting to university campuses is an expensive activity for most students, particularly during a time of rising living costs in an urban city such as London; and less time spent traveling means more time for study at home and clinical placements.

“It (digital education) saves a lot of money and time wasted on commuting, we are already in so much (demand) because we are on clinics. I would be finished/tired if we had in-person lectures.”(Student)

3.1.3. Authentic Learning for a Post-Digital World

The world is heavily digital, to the extent that our boundaries of online and face-to-face are increasingly blurry. The world of medicine and dentistry, especially, demands, and assumes, a certain level of digital literacy [20,21]. The university needs to therefore design teaching contexts to be authentic for our students getting ready for the future work force.

“Post-digital world—authentic learning—society is becoming more digital and the university should help equip students for the skills they need.”(Staff)

Generative Artificial Intelligence, GenAI for short, has, in recent times, activated considerable disruption and concern for academic integrity and the ways in which assessment in particular, is designed and conducted within the higher education sector. While the detection of academic misconduct is a real challenge with such generative AI technology, the current discourse is that education providers must now educate our students to appropriately use AI, so that they are ready for the post-digital world, where AI will co-exist with our lives and work [22,23].

3.1.4. Business Proposition

Alongside the university’s strategy, the faculty’s enabling plan clearly outlines its ambitious targets, in particular for postgraduate programme expansion and growth in student numbers, and improvements in national rankings on student experience and outcomes (e.g., the National Student Survey). The community is aware that digital education will play an important role in achieving these targets. The majority of undergraduate programmes, namely the MBBS and BDS, are capped for clinical places already in high demand; therefore, the proposed expansion areas are primarily postgraduate and non-clinical, distance and digital learning programmes. These courses can expand within the Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs), without having to rely on the highly limited physical and clinical learning spaces. It was also highlighted that non-credit-bearing courses, in the form of short online CPD courses, are a potential area for expansion and generation of income. In essence, digital education is often framed as a ‘business proposition’ and source of income for the university’s growth, aside from an educational and pedagogical proposition.

3.1.5. Pastoral Care—The Community as a Family

Finally, the notion of pastoral care is something that is believed to be unique among the community. In 2023, the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry is celebrating hundreds of years of history, stemming from its esteemed establishment and association with the original hospital, and this illustrious history is held close to the hearts of students and staff. This brand and reputation have attracted generations of successful and aspiring doctors, dentists, and health professionals to the faculty. Staff and students proudly discussed the enriched culture and sense of belonging, underpinned by the pastoral care and ‘family’-like connection within and outside of their learning, in showing care for one another as a community. Staff and students framed digital technologies and education as enabling and fostering this culture and helping to build relationships.

3.2. Opportunities and Challenges

Building on the above-mentioned beliefs the community held on digital education for medical curriculum, in what follows, the eight key opportunities and challenges highlighted by staff and students are discussed, in relation to current and past practices of teaching and learning online. They are in most cases two sides of the same coin in that, where challenges or inhibitors were noted, they were deemed to be opportunities or potential enablers for improvements and change. Where relevant, student- and staff-specific views are highlighted with illustrative quotes.

3.2.1. Human Relationships

Closely related to the value of (pastoral) care mentioned above, the staff and students pay close attention to the importance of relational aspects for online learning and teaching. The pandemic escalated the sense of isolation and disconnection among teachers and students that was known to exist within online learning [24,25]; and they argued that the sense of belonging and the human relationships that connect online and on-location learning were critical to their success and well-being at the university.

“Mental health and lack of human contact are related.”(Student)

3.2.2. Co-Creation with Students and Clinicians

It is believed that learning and teaching are better when co-created in partnership among students and staff. They also highlighted that the nature of the medical curriculum lends itself to involving diverse partners in clinical and science education, such as NHS clinicians, clinical researchers, and industry partners. This co-creation also offers an authentic learning opportunity to equip students for a world of work that requires teamwork, collaboration, and empathy in health professionals for patient care. Students in the co-lab session talked about the novel idea of a ‘Digital Learning Student Ambassador’ who could contribute to harnessing the student voice to involve students with decision-making processes around digital education initiatives at the faculty.

“It would be good to have a co-creation process to incorporate student voice in decision making.”(Student)

3.2.3. Digital Engagement

It was noted that the university could improve ‘digital engagement, presence or outreach’, noting numerous world-renowned academics and researchers. This highlights that although the university maintains such a “reputational value that [it has] some established courses with a good reputation and brand” (Staff), it does not communicate to the public adequately enough about those impactful researchers and their work. While aspects of the above mostly relate to the marketing and reputational impact, this translates into teaching contexts as well, with limited teacher–student interaction or engagement at play in digital learning environments. Teacher presence, along with cognitive and social presence, is critical to productive and safe learning online [26], and the university needs to do much to build its digital engagement both within online teaching and outreach into the public sphere with its current, past, and future community.

“Staff need to be more out there online. The university needs to help staff connect more with students.”(Staff)

3.2.4. Digital Pedagogy

Digital education demands its own pedagogy [16]. In other words, the simple translation and replication of moving teaching practices from face-to-face to online does not work [27]. Yet the pandemic forced all teachers and universities to at least implement ‘digital delivery’ in an emergency manner—‘panic-gogy’ and ‘emergency remote teaching’ became prevalent terms to describe much of the online teaching practice during this period [1,2]. A few years on, educators expressed strong enthusiasm for learning more about digital pedagogy and applying evidence-based approaches to practice with a critical lens. In particular, staff were interested in how best to: scaffold learning and flip classrooms for active learning within digital learning environments; teach students online for pre-clinical preparatory work through simulation; and design for and facilitate small group discussion better online, in effective ways. Students highlighted that small group discussion worked particularly well for their deeper and social learning online.

“The small group teaching sessions can be good. Anatomy in 2nd year during COVID was better than practical as we got more teaching.”(Student)

3.2.5. Digital Literacy

Teaching and learning well online not only requires appropriate pedagogies, but also digital literacy—the ability to use technologies to read, write, create, and carry on our lives as our authentic selves [20,21,28]. Digital literacy goes beyond traditional Information and Communication Technology (ICT) skills and includes the broader meaning of ‘literacy’—that one can essentially ‘navigate the world’ with various competencies to perform as one’s authentic self online. Some educators feel less confident about this and require support in quickly learning to adapt and apply new technologies to teaching online. Equally, for students, learning online requires a particular type of self-regulated learning that requires high levels of digital literacy. Students not only need to know how to use technologies, but also how to incorporate them to: express themselves and be humans in digital learning; engage with others to produce work; and demonstrate skills that are of certain standards and quality. In short, there was a sense that support is needed to develop digital literacy skill sets not only as essential skills in teaching and learning online, but also as 21st-century skills to live and thrive in a post-digital world.

“Staff have less knowledge on how to use these online resources, students end up teaching staff members.”(Staff)

3.2.6. Edtech—IT Infrastructure

In digital education contexts, we want educational technologies to be almost invisible and not the foci of discussion or practice, so that teaching can be carried out fruitfully. This is of course the case when edtech is working in the ways that we expect. However, when edtech is not working accordingly, we notice it a lot more as an inhibitor and detractor to teaching practice. It is important to also note that in the online surveys, there were some students who included a ‘stable and fast internet connection’ as one of the supports they required ‘to be able to study well online’, indicating that there are still some digital divide and access issues amongst the students.

Overall, staff and students exhibited a palpable sense of dissatisfaction related to technology failure, lack of support, and poor user experiences. In particular, hybrid teaching has been a heightened issue with edtech often failing in teaching spaces. The (mis)use of edtech of course contributes to the digital and physical fatigue many people reported during the pandemic.

3.2.7. Support–Digital Literacy, Digital Pedagogy, and Time/Workload Allocation

Most of the students and staff are incredibly busy and time-poor. Staff expressed the need for support, including adequate time allocation and a reward system for professional development to help build their digital education capabilities. It is widely acknowledged that the design, development, and delivery of premium digital learning courses are labour-intensive and highly specialised, with lots of upfront investment of time and expertise required [4,19].

“There is an urgent need for training. Many academics have taught in the same way for their whole careers and within the last few years education has changed beyond recognition. They need support to get on board with that change.”(Staff)

3.2.8. Assessment and Feedback

Assessment and Feedback continues to be a central point for discussion and improvement in higher education, as the National Student Survey continues to highlight the need for improvement in this particular area. There was a sense that assessment and feedback should be performed better online, particularly in the post-pandemic era, against the threat of emerging technologies such as GenAI. Staff saw opportunities for a more holistic and authentic design across formative and summative tasks. With the rising number of academic misconduct cases and the threat of AI-generated text being used in written assessment and exams, future work must include strategic projects to improve our assessment and feedback practices.

“We need support with better explanation, what we need to know for assessments”(Student)

Table 2 below summarises the above findings—namely, values and beliefs; what people perceived to be the driving force behind the practice of digital education within the context of this faculty, and also the eight key themes of challenges and opportunities found to be evident in digital teaching and learning among the community of staff and students in the medical curriculum.

Table 2.

Summary of key findings in the report.

4. Discussion

The key findings set out above highlight some synergy with the literature surrounding what drives universities to pursue digital education within the higher education sector that goes beyond ‘panic-gogy’ [2,29,30]. This argument broadly centres on the two key aspects—(i) developing one of the key graduate attributes of digital, AI and data literacy for a post-digital world and world of work [31,32], and (ii) university expansion of student recruitment given the limited physical learning and teaching spaces on university campuses [33].

With the limited literature exploring the importance of a ‘contextualised’ understanding of the opportunities and challenges that universities face in their digital education endeavours, this study bears implications for the practice of transforming digital education to be situated within a specific organisation, as outlined above through the collective discovery and sharing of the key insights to craft and implement innovation.

Within the context of this university, upon the completion and dissemination of the review report, outlining the results above, the digital education strategy, which consists of the two innovation project briefs, was drafted at the beginning of 2023. First, the CARE digital project was developed, where six selected online programmes are being developed to address the above concerns, while creating showcase programmes of best practice in digital education, with a multidisciplinary digital education team of learning designers, creatives, and project managers. And secondly, the digital assessment and feedback tool pilot with Cadmus, the ‘Assessment for learning’ platform, was deployed as a catalyst to transform digital assessment and feedback practices for authentic assessment. These two strategic innovation projects have been implemented and progressing since 2023, with an ongoing evaluation of their effectiveness to improve digital teaching and learning practices.

The limitation of this paper stems from the incompleteness of the evaluation of those strategic projects still in progress, though this also presents an opportunity for further research. This therefore highlights the future direction of this study: building the scholarship around the effectiveness of implementing contextualised digital education innovation work.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study builds on the essence of Bayne and Gallagher’s work [8], namely, the importance of co-design and bottom-up approaches to bring about meaningful change for a post-digital world of medical education. With the backdrop of increasing narrative on AI-enabled, digital futures within higher education, it is vital that humans re-imagine and drive their own future, along with robots, through collective and creative leadership.

Importantly, this paper not only makes a contribution to the gap in the existing literature, but also encourages other universities and medical educational leaders to reflect on their future digital strategies and foster the culture of collective imagining, bottom-up change process for educational innovation in a post-digital world. In such a collective endeavour, the leadership team needs to be mindful of the dynamic nature of such a co-design project, which involves large number of stakeholders; this process therefore needs to include some level of ‘buffer’ in shifting timelines and deliverables, working with ever-busy students and academics.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical review and approval were exempt from the research ethics committee of Queen Mary University of London as the paper is considered as a ‘service evaluation’ and a means of setting internal policy in improving learning and teaching practices (the formal letter was received on 28 June 2023). The final institutional report, containing the key findings of this paper, was circulated within the university.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge and thank those who have participated and helped facilitate this large-scale consultation and explorative study within the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry. In particular, my sincere thanks goes to the student partner, Sabir Anwar Saleh, who was a third-year dental school student at the time, for providing considerable support and acute insight into shaping this study to infuse it with the student voice, and also to the Communication and Event Manager, Michal Bilewicz who created the infographic (Figure 1).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Digital Education Experience Survey—Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry (FMD) Students, 2022

Thank you for participating in this survey. This is an online survey to help all students within the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry to better understand their experiences with digital learning. It is part of the Discovery towards Strategy project led by the Dean for Digital Education, along with the student representative (a 3rd-year dentistry student), so that we can co-create the future strategy to transform our online learning and teaching practices.

If you would like to be entered into the prize draw to win one of ten £10 vouchers, please enter your email at the end of the form; this will be used purely for the prize draw and your submission will not be associated with your email.

Your information will be kept confidential and privately unless you let us know that you are happy to provide your personal details. The survey will take approximately 5 min to complete.

If you have any questions or concerns, please feel free to contact: [email address]

Required

| 1. | What course are you part of, within the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry? |

| 2. | Are you an undergraduate or a postgraduate student? * |

| ○ Undergraduate | |

| ○ Postgraduate | |

| 3. | What year are you in? * |

| ○ Year 1 | |

| ○ Year 2 | |

| ○ Year 3 | |

| ○ Year 4 | |

| ○ Year 5 | |

| ○ Intercalating | |

| ○ Other | |

| 4. | Why is digital education important to you? |

| 5. | What support do you need to be able to study well online? |

| 6. | What technologies do you use for learning online? List the top 5 tools you use most. |

| 7. | Please select the options which match your opinions about the following statements. * |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I find [LMS] easy to use | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| [LMS] courses give me a great experience | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The new update has improved [LMS] | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy pre-recorded lectures | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy live online lectures | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy in-person lectures | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy small group online teaching | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I am happy with my current exam conditions | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I learn better with a mix of online and in-person teaching | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I find it easy to use my timetable | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| It is easy to socialise with my peers online | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Online learning is better for my university/life balance | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I learn better with online teaching than in-person teaching | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I learn better with only in- person teaching | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy Mixed Mode Education (MME) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| 8. | What is working well for digital education within the FMD? |

| 9. | What is not working well for digital education within the FMD? |

| 10. | What can be improved for digital education within the FMD? |

| 11. | Do you have any other comments or feedback you would like to add? |

| 12. | If you are happy to be contacted for further conversation around your digital learning experience, please leave your email address below: |

| 13. | If you would like to be entered to the prize draw, please enter your name and email here; this will not be used for any purposes other than to contact you if you have won the prize draw. |

Appendix B. Digital Education Experience Survey—Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry (FMD) Staff 2022

Thank you for participating in this survey. This is an online survey to help all staff within the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry to better understand their experiences with digital education (i.e., teaching and learning online). It is part of the Discovery towards Strategy project led by the Dean for Digital Education, so that we can co-create the future strategy to transform our online learning and teaching practices.

Your information will be kept confidential and privately unless you let us know that you are happy to provide your personal details. The survey will take approximately 10 min to complete.

If you have any questions or concerns, please feel free to contact: [email address]

Required

| 1. | What course are you part of, within the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry? |

| 2. | Which course do you teach? * |

| ○ Undergraduate | |

| ○ Postgraduate | |

| ○ Other | |

| 3. | Which year do you teach? |

| □ Year 1 | |

| □ Year 2 | |

| □ Year 3 | |

| □ Year 4 | |

| □ Year 5 | |

| □ Other | |

| 4. | Tell us what you see “digital education” as. |

| 5. | Why is digital education important for the FMD and Queen Mary? |

| 6. | What values do you want to see driving our digital education within the FMD? |

| 7. | What do you think teachers need to be able to teach online well? |

| 8. | What support is currently available to teach online well? |

| 9. | What technologies do you use for teaching online? List the top 5 tools you use most. |

| 10. | Please select the options that match your views about the following statement. * |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I find [LMS] easy to use | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The new update has improved [LMS] | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy recording lectures in advance | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy teaching live online lectures | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy teaching in-person lectures | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy teaching Mixed Mode Education (MME) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I enjoy small group online teaching | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| It is easy to facilitate peer- learning onling | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I find it easy to use timetabling | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I would like to go back to the way I was teaching pre-pandemic | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Support resource/training is available to teach online well | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| 11. | What is working well for digital education within the FMD? |

| 12. | What is not working well for digital education within the FMD? |

| 13. | What can be improved for digital education within the FMD? |

| 14. | Who is doing interesting work regarding digital education? Tell us about their practice. |

| 15. | Are you aware of any open/short courses? (e.g., continuous professional develop-ment/CPD, MOOCs, executive education, summer school) - If yes, please list them. |

| 16. | Do you conduct research for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL)? If so, what area? And why is this important/beneficial to you? |

| 17. | What is different/the same (compared to pre-pandemic), in your digital teaching? |

| 18 | What would you like to start/stop/continue doing in your digital teaching (compared to pre- pandemic)? |

| 19. | Do you have any other comments or feedback you would like to add? |

| 20. | If you are happy to be contacted for further conversation around your digital teaching experience, please leave your email address below: |

References

- Hodges, C.B.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.B.; Trust, T.; Bond, M.A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning; Educause: Denver, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, K.J. Panic-Gogy: A Conversation with Sean Michael Morris. In The National Teaching & Learning Forum; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spinks, M.L.; Metzler, M.; Kluge, S.; Langdon, J.; Gurvitch, R.; Smitherman, M.; Esmat, T.; Bhattacharya, S.; Carruth, L.; Crowther, K. “This Wasn’t Pedagogy, It Was Panicgogy”: Perspectives of the Challenges Faced by Students and Instructors during the Emergency Transition to Remote Learning Due to COVID-19. Coll. Teach. 2021, 71, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S. What might learning design become in the post-COVID university? Learn. Des. Voices 2022, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurillard, D. Teaching as a Design Science: Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi, C.; O’Donnell, M.; Elliott, J. Co-creating a digital learning innovation framework through design thinking approaches. In Reconnecting Relationships through Technology. Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Innovation, Practice and Research in the Use of Educational Technologies in Tertiary Education, ASCILITE; Sydney, NSW, Australia, 4–7 December 2022, Wilson, S., Arthars, N., Wardak, D., Yeoman, P., Kalman, E., Liu, D.Y.T., Eds.; Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education: Tugan, QLD, Australia, 2022; p. e22140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, A.P.; Leffel, K.G.; Lott, M. Plotting Academic Innovation: A Content Analysis of Twenty Institutional Websites. Innov. High. Educ. 2021, 47, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, S.; Gallagher, M. Near Future Teaching: Practice, policy and digital education futures. Policy Futures Educ. 2021, 19, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joughin, G.; Bearman, M.; Boud, D.; Lockyer, J.; Adachi, C. Creating and sustaining collaborative connections: Tensions and enabling factors in joint international programme development. High. Educ. 2022, 84, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.T.; Preskill, H.; Tzavaras Catsambas, T. An overview of appreciative inquiry in evaluation. New Dir. Eval. 2003, 2003, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, D.; Cooperrider, D. Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change; Berret-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C. Opportunity through Online Learning: Improving Student Access, Participation and Success in Higher Education; The National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education (NCSEHE), Curtin University: Perth, WA, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, S.M.; Stommel, J. An Urgency of Teachers: The Work of Critical Digital Pedagogy; Hybrid Pedagogy: Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, C. Online learning in Australian higher education: Opportunities, challenges and transformations. Stud. Success 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.; O’Shea, S. Older, online and first: Recommendations for retention and success. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, P. Teaching as Design. HERDSA Rev. High. Educ. 2015, 2, 27–50. Available online: https://petergoodyear.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/goodyear-2015-teaching-as-design.pdf (accessed on 27th September 2024).

- Adachi, C.; Blake, D.; Riisla, K. Exploring digital literacy as a graduate learning outcome in higher education—An analysis of online survey. Open Oceans: Learning without borders. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference of Innovation, Practice and Research in the use of Educational Technologies in Tertiary Education, Geelong, VIC, Australia, 25–28 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell-Neilson, J. Digital Literacy–a driver for curriculum transformation. In Proceedings of the HERDA 2017: Research and Development in Higher Education: Curriculum Transformation: Proceedings of the 40th HERDSA Annual International Conference, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 27–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lodge, J.M.; Howard, S.; Bearman, M.; Dawson, P.; Agostinho, S.; Buckingham Shum, S.; Deneen, C.; Ellis, C.; Fawns, T.; Gniel, H. Assessment Reform for the Age of Artificial Intelligence; Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lodge, J.M.; Thompson, K.; Corrin, L. Mapping out a research agenda for generative artificial intelligence in tertiary education. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Händel, M.; Stephan, M.; Gläser-Zikuda, M.; Kopp, B.; Bedenlier, S.; Ziegler, A. Digital readiness and its effects on higher education students’ socio-emotional perceptions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2020, 54, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; McIntyre, S.; McArthur, I. Trust and relationship building: Critical skills for the future of design education in online contexts. Iridescent 2011, 1, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R. Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2007, 11, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, S.; Evans, P.; Ewins, R.; Knox, J.; Lamb, J. The Manifesto for Teaching Online; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pangrazio, L. Reconceptualising critical digital literacy. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2016, 37, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Selwyn, N.; Aston, R. What works and why? Student perceptions of ‘useful’ digital technology in university teaching and learning. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenovic, J. The future of value in digitalised higher education: Why data privacy should not be our biggest concern. High. Educ. 2022, 83, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupichler, M.C.; Aster, A.; Schirch, J.; Raupach, T. Artificial intelligence literacy in higher and adult education: A scoping literature review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, M.R.; Jones, S. Digital literacies in higher education: Exploring textual and technological practice. Stud. High. Educ. 2011, 36, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, J. Building Better Universities: Strategies, Spaces, Technologies; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).