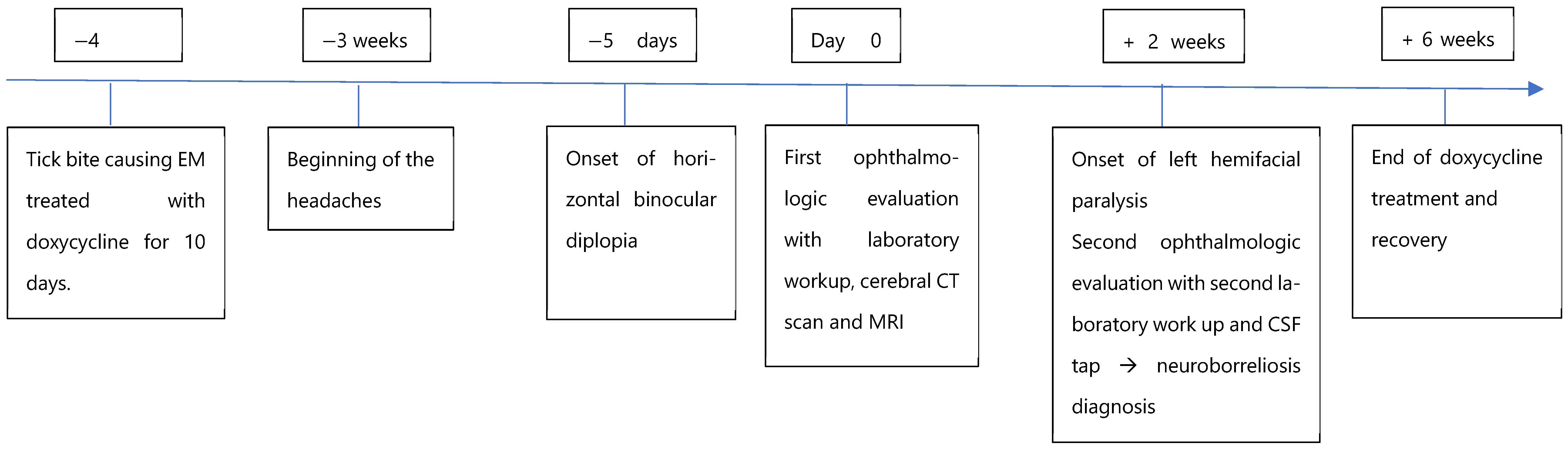

3.1. Sixth Nerve Palsy: Causes, Diagnostics, and Management

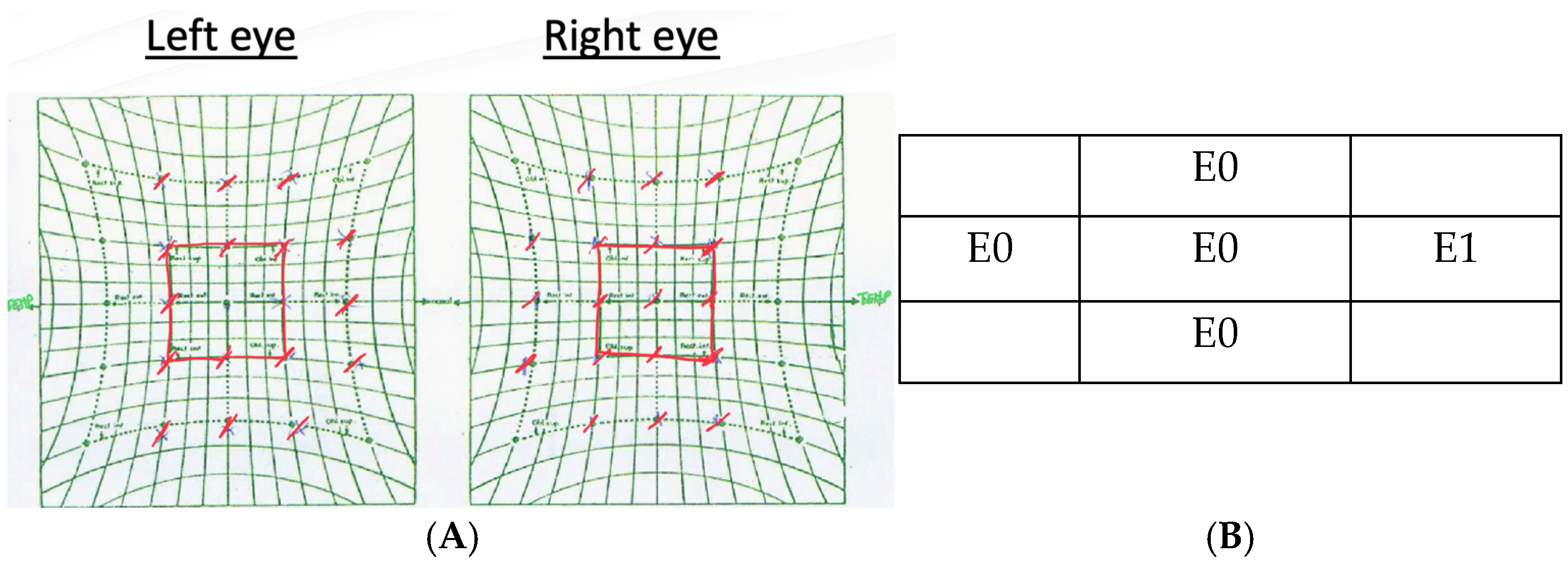

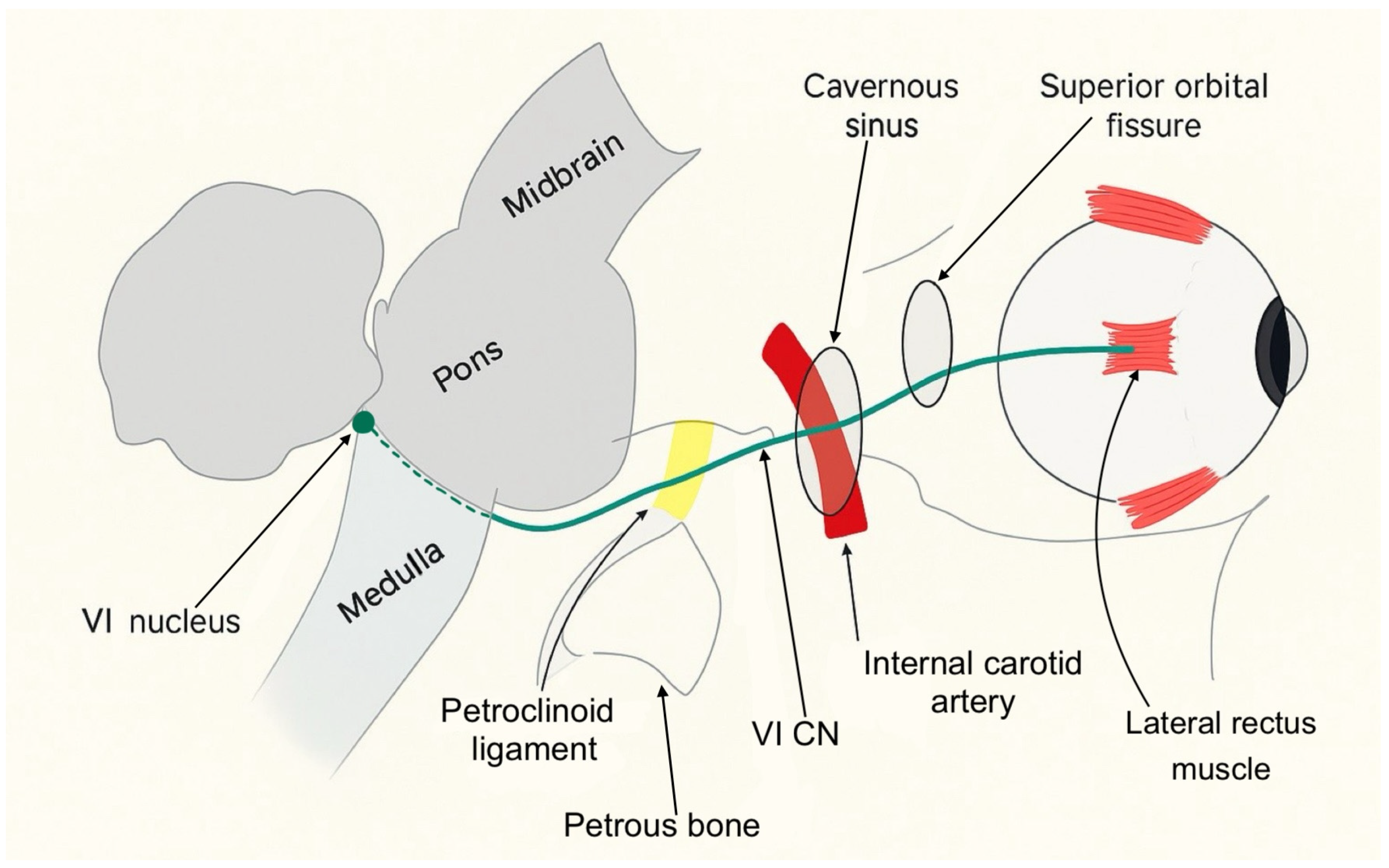

Most sixth nerve palsies are unilateral and acquired. They typically present with new-onset horizontal diplopia and impaired abduction of the affected eye. Immunologic or viral injury to the sixth cranial nerve can occur at any point along its course. As illustrated in

Figure 9, the sixth cranial nerve, also known as the abducens nerve, has a long course extending from the sixth nerve nucleus in the dorsal pons to the lateral rectus muscle within the orbit. Its anatomy makes it vulnerable to injury at numerous points. Sixth nerve palsies can be classified into distinct syndromes based on the anatomical location of the nerve involvement: brainstem syndrome, petrous apex syndrome, cavernous sinus syndrome, orbital syndrome, and isolated sixth nerve palsy. Each of these regions has characteristic associated signs that can help localize it.

The brainstem syndrome can involve the fifth, seventh, and eighth cranial nerves, as well as the pyramidal tract on the anterior aspect of the pons and the cerebellum behind it. The petrous apex syndrome concerns the course of the sixth cranial nerve under the petro-clinoid ligament. In this area, the ipsilateral fifth, seventh, and eighth cranial nerves can become involved. When the injury is located within the cavernous sinus, the sixth nerve palsy is often associated with a dysfunction of the third, fourth, and fifth (ophthalmic and maxillary divisions) cranial nerves. Involvement of the internal carotid artery and the carotid sympathetic plexus is also possible. Finally, if the sixth cranial nerve is injured within its orbital course, the optic nerve and the ophthalmic and maxillary division of the fifth cranial nerve may be affected. Proptosis is an early sign of the orbital syndrome and is frequently accompanied by conjunctival hyperemia and chemosis [

1,

2].

Isolated sixth nerve palsy in adults is most commonly caused by microvascular ischemia, often related to systemic pathologies such as diabetes mellitus, arteriosclerosis or systemic hypertension. However, it may also occur secondary to elevated intracranial pressure. In fact, approximately 19% of patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension have been diagnosed with sixth cranial nerve palsy [

5]. Infectious causes such as Lyme disease or syphilis are uncommon and account for only a small proportion of cases [

6]. A retrospective study found that trauma is responsible for about 3% of isolated sixth nerve palsy [

7]. Demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis have been reported in 8% of nontraumatic, isolated sixth cranial nerve palsies in a retrospective population-based case series [

8]. In this context, our patient’s treatment with infliximab raised concern. In fact, TNF-α blockers have been associated with central and peripheral nervous system (CNS) demyelination. [

9]. In addition, in this young patient with an isolated sixth nerve palsy, infectious etiologies were also a primary consideration due to immunosuppression.

It is important to consider other conditions that can mimic sixth nerve palsy, including thyroid eye disease and myasthenia gravis [

1,

2]. Prompt differentiation of these entities is essential to avoid unnecessary imaging and to detect potentially more serious underlying diseases.

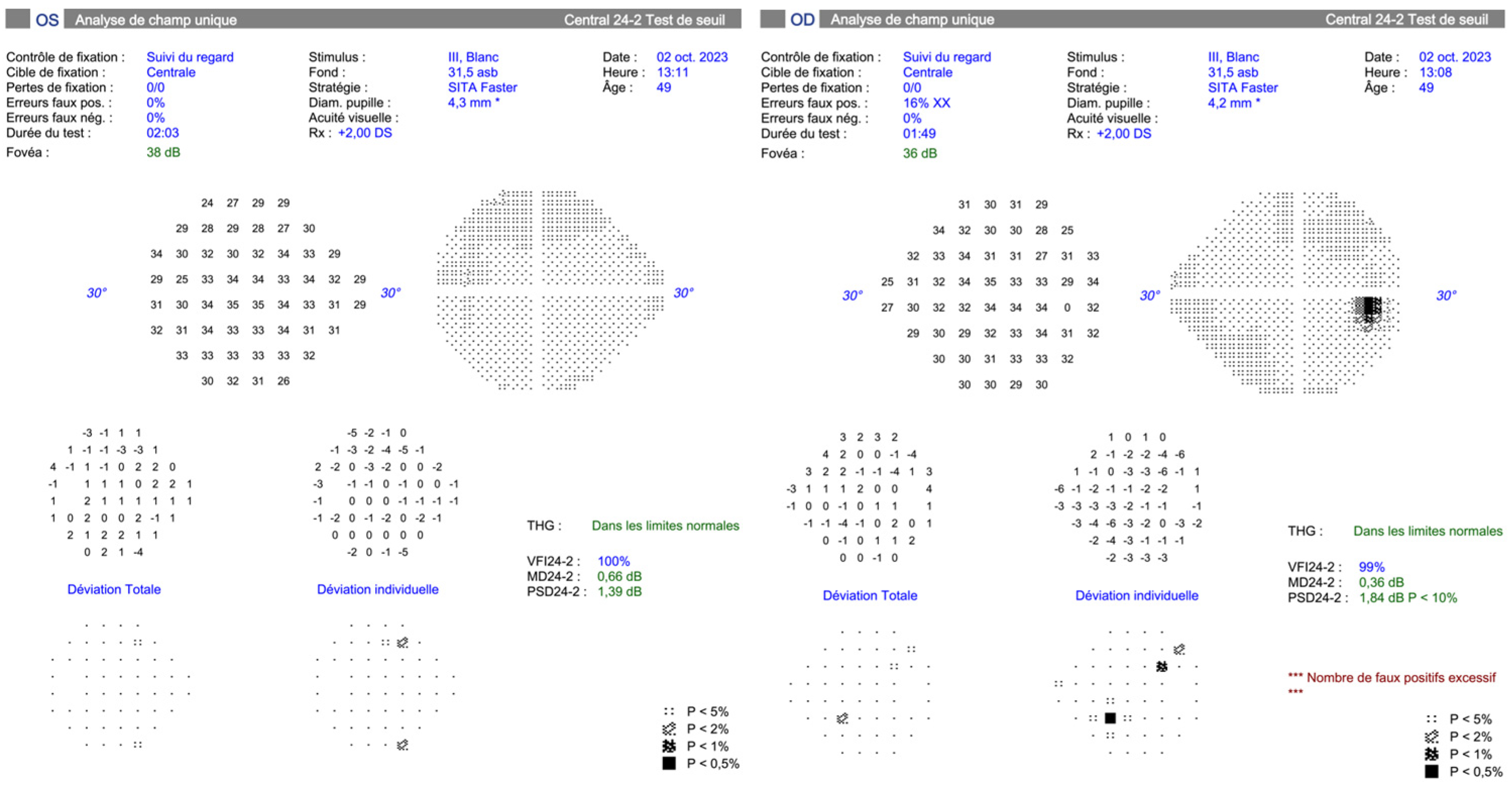

A thorough ophthalmologic examination is mandatory in any patient presenting with acute diplopia or suspected sixth nerve dysfunction. This examination should include the assessment of visual acuity, intraocular pressure, pupillary light reflexes, and motility deficits to document the degree of lateral rectus weakness. Examination of the anterior and posterior segments of the eye, including a dilated fundus evaluation, is important to detect papilledema or other retinal and choroidal findings that might signal raised intracranial pressure or a systemic inflammatory disease. A complete cranial nerve and neurologic examination should also be conducted since additional nerve involvement can redirect the diagnostic workup toward brainstem, petrous apex, cavernous sinus, or orbital apex pathology [

2].

The workup should include laboratory tests such as complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), CRP, syphilis testing, Lyme antibody testing, glucose levels or hemoglobin A1c, thyroid function tests, and myasthenia gravis antibodies [

2].

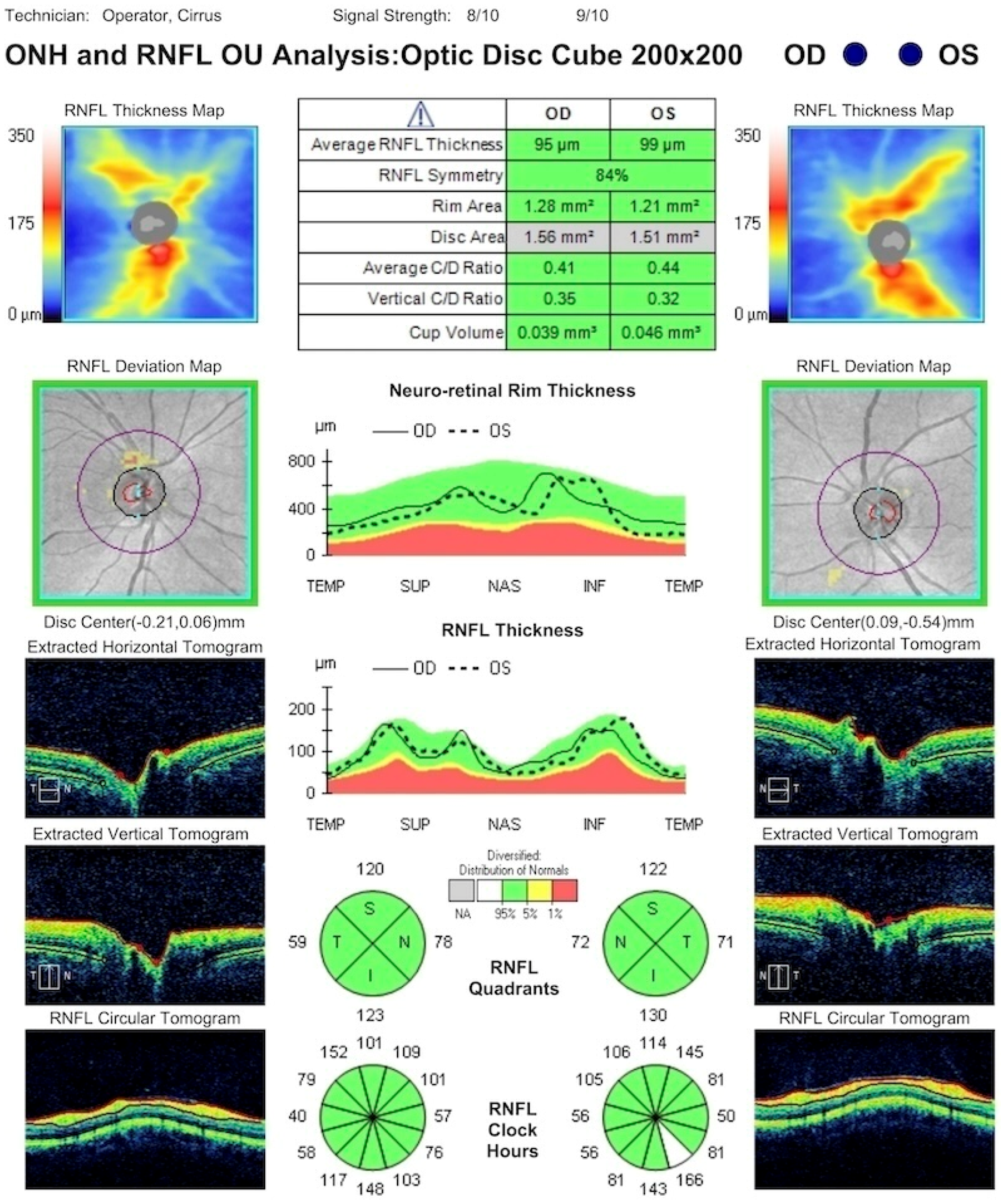

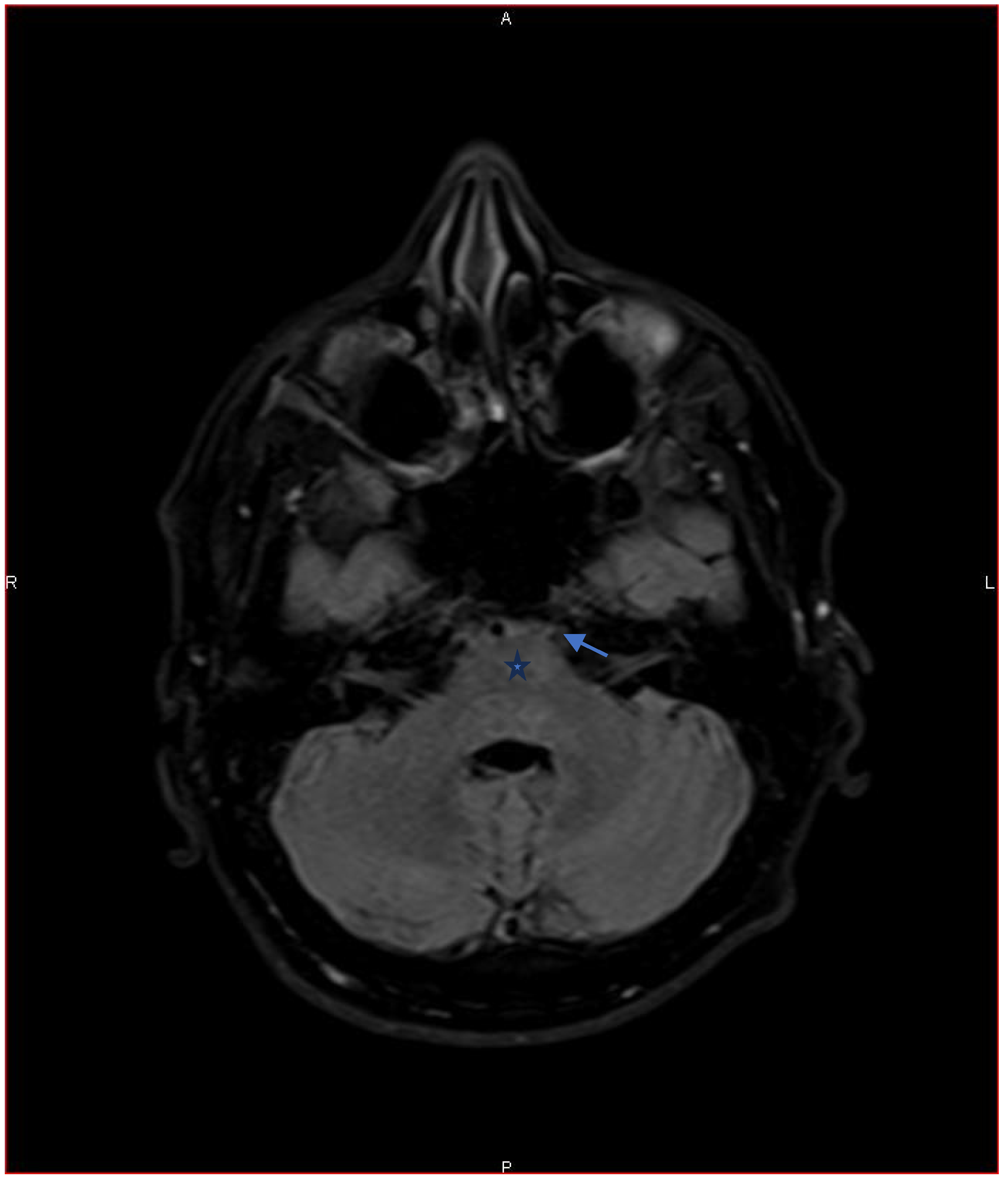

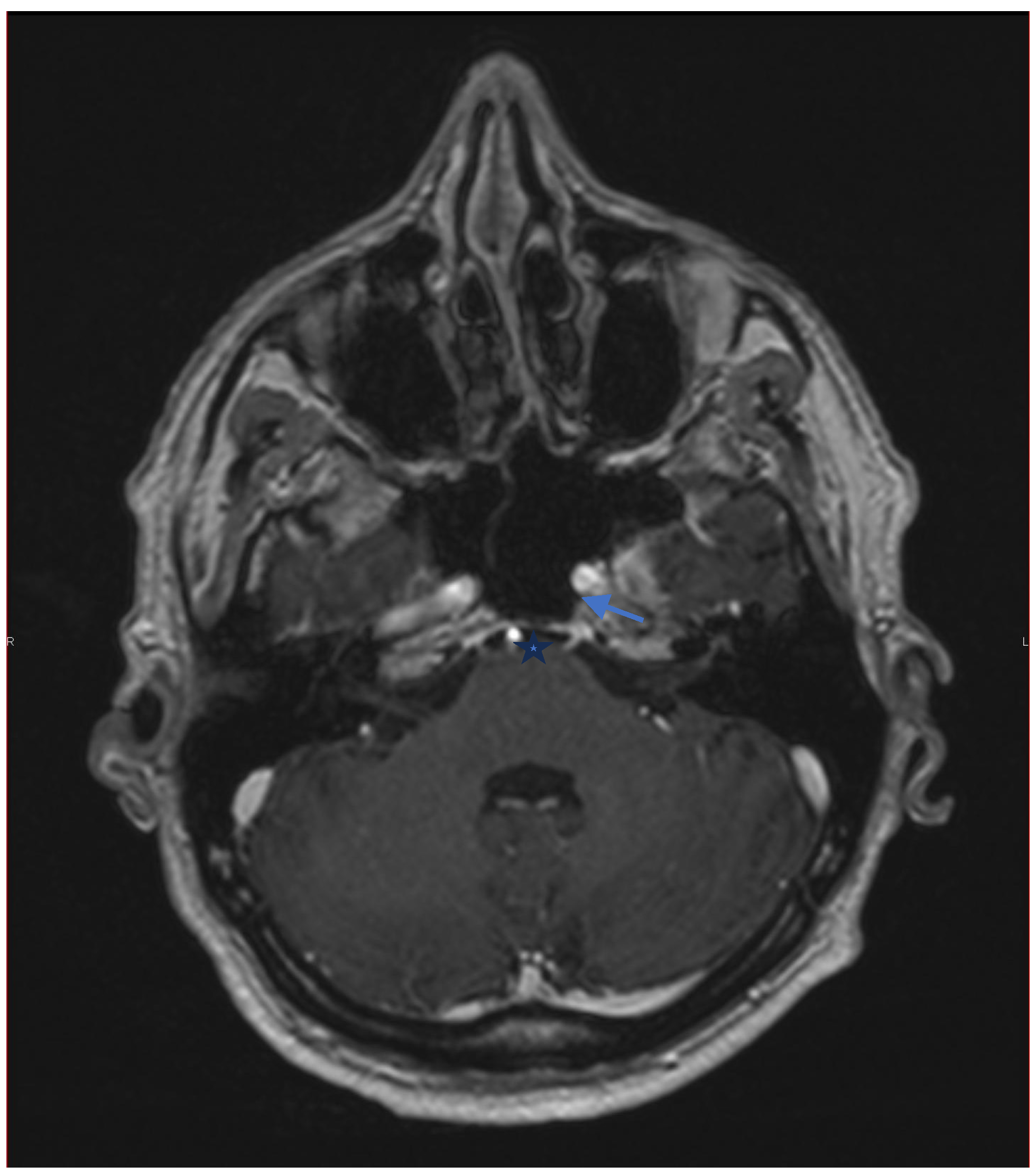

Neuroimaging is recommended in patients with an atypical clinical presentation, age under 50 years, or persistent symptoms beyond three months to rule out compressive, inflammatory, or demyelinating lesions. Brain MRI with gadolinium is preferred, as it can detect small enhancing lesions of individual cranial nerves [

10]. Computed tomography of the orbits and skull base may also be considered if bone or sinus pathology is suspected. In our case, MRI ruled out a demyelinating disorder related to TNF-α inhibitor therapy. Careful review of the gadolinium-enhanced images showed neuritis affecting the sixth cranial nerve.

As previously discussed, sixth cranial nerve palsy can have multiple etiologies and the underlying cause largely determines the extent of recovery which may be complete or, in some cases, absent. Persistent paresis can result in chronic esotropia and diplopia, causing significant functional impairment and reduced quality of life in affected patients.

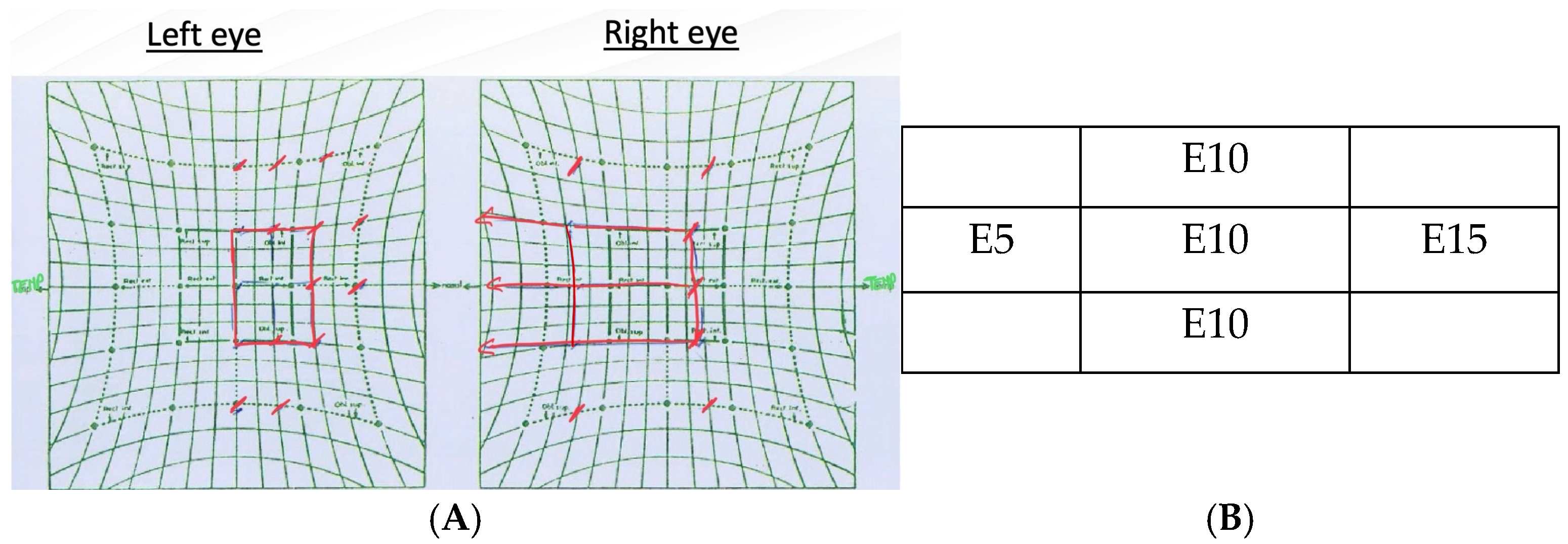

To alleviate the patient’s discomfort during the diagnostic workup, interim measures such as Fresnel prisms may be proposed. Fresnel prisms, thin and flexible plastic lenses affixed to the patient’s glasses, can provide temporary optical compensation for a defined angle of ocular misalignment [

2]. The use of prism correction was highly effective in managing the binocular diplopia in our patient.

In the early stages, the use of botulinum toxin can also be useful. Injection of botulinum toxin into the ipsilateral medial rectus (MR) weakens its contractile force, preventing secondary contracture and improving the effectiveness of prismatic correction in cases of marked deviation [

2].

For long-term management, ground-in prisms—prisms permanently incorporated into the spectacle lenses—offer a cosmetically superior alternative to Fresnel prisms, albeit at a greater expense. If the palsy does not resolve after 6 to 10 months, a surgical intervention is indicated. The primary objectives are to expand the binocular diplopia-free field, improve abduction, and restore primary-position alignment. Patients with partial left rectus function typically undergo horizontal muscle surgery, whereas complete left rectus palsy requires a distinct strategy such as vertical rectus muscle transposition [

11,

12].

3.2. Lyme Disease: An Overview

There are three stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated. Early localized infection typically occurs days to weeks after the tick bite. It manifests with an expanding erythematous rash called EM that appears at the site of the tick bite and is often accompanied by flu-like symptoms. If left untreated, weeks to months later, the infection can spread hematogenously, leading to early disseminated Lyme disease, which can manifest as multiple EM lesions, facial palsy, meningitis, or carditis. Cranial nerve seven is the most common cranial nerve affected by Lyme disease [

13]. Some authors suggest that inflammatory edema may easily damage the facial nerve due to its long intraosseous course [

14]. Late disseminated disease occurs months to years after an untreated infection and can lead to encephalomyelitis, encephalopathy, chronic arthritis, or chronic atrophying acrodermatitis [

13].

Lyme disease can also produce a wide array of ocular findings. The literature describes follicular conjunctivitis, which may be unilateral or bilateral and occasionally severe enough to cause marked eyelid edema. Other reported presentations include interstitial or ulcerative keratitis, episcleritis, scleritis, orbital myositis, uveitis (anterior, intermediate, or posterior), optic neuritis, and oculomotor palsies affecting the third, fourth, or sixth cranial nerves [

15]. These diverse signs underscore the need for ophthalmologists to maintain a high index of suspicion in endemic areas, especially when conventional causes of cranial nerve palsy are not apparent.

Lyme neuroborreliosis encompasses all the neurologic manifestations caused by Borrelia burgdorferi. Early neuroborreliosis manifests during the first two stages of Lyme disease, with Bannwarth syndrome being the most frequent presentation. This syndrome is characterized by the triad of lymphocytic meningitis, cranial nerve damage, and radiculoneuritis. Late neuroborreliosis develops in 5% of untreated patients and can lead to irreversible nerve damage, headache, fatigue, paresthesia, chronic neuropathic pain, and cognitive impairment [

4].

Diagnostic criteria for early neuroborreliosis comprise a typical clinical presentation (cranial nerve involvement, meningitis), positive serological testing (ELISA with confirmatory Western blot showing abnormal IgM and/or IgG antibodies), and an inflammatory CSF profile with lymphocytic pleocytosis, evidence of blood–CSF barrier dysfunction, and intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis. The antibody index, which is the ratio of specific antibodies in CSF compared with serum, has a high specificity (97%) but only moderate sensitivity (40–89%) [

16,

17].

Borrelia-specific IgM and IgG antibodies typically become detectable approximately 3 weeks and 6 weeks, respectively, after symptoms onset [

16]. IgM antibody levels usually decline after one month and may be absent in reinfections. IgG antibodies may remain positive for years and may increase with longer disease duration. Seropositivity can also persist after subclinical Borrelia infection. This persistence likely contributes to the high rate of false positive serologies in endemic areas [

16,

18]. Furthermore, serum antibody specificity is low [

4]. This explains why the patient’s initial positive IgG was initially overlooked.

In neuroborreliosis, intrathecal production of Borrelia-specific antibodies begin around 2 weeks after symptom onset. It is detectable in more than 99% of patients after 6 to 8 weeks [

16]. In our case, all diagnostic criteria were met. He presented with early onset neuroborreliosis.

The patient’s headaches warrant careful consideration. Headache is very common, especially in young adults. In the absence of focal neurological signs or systemic symptoms, it usually does not prompt further investigation. However, in this case, the headaches could indicate early central nervous system involvement and may represent the first symptom of neuroborreliosis. They were likely caused by early neuroborreliosis-related meningitis. They may also have been partially related to gradual onset of diplopia, which can induce patient’s discomfort.

Neurologic symptoms worsened over time. Serum IgM antibodies were absent from the beginning, while IgG levels rose between the first and second workups. Lymphocytic pleocytosis with intrathecal antibody synthesis was present. Together, these findings indicate an early onset neuroborrelioses following the initial erythema migrans episode. In this immunocompromised patient, the first doxycycline course was likely insufficient, allowing disease progression. Considering the timeline, patient history and immunologic findings, reinfection seems unlikely.

The treatment for patients with acute neurological disease due to Borrelia infection is based on one of the following regimens for 14 to 21 days: oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for adults), ceftriaxone (2 g IV once a day), cefotaxime (2 g IV every eight hours) [

16]. According to the EFNS (European Federation of Neurological Societies), the outcomes with the use of oral doxycycline (200 mg daily) and IV ceftriaxone (2 g daily) for 14 days were the same [

4].

Treatment depends on disease severity, patient tolerance, comorbidities, and local resistance patterns. In our case, the patient was receiving infliximab for Crohn’s disease and was therefore immunocompromised. Several case reports have described early Lyme borreliosis in immunocompromised patients [

19]. His immunocompromised state may have contributed to the atypical presentation and to disease progression despite appropriately treated erythema migrans.

Given the risks of discontinuing infliximab and the severity of the condition, we continued the immunosuppressive therapy and extended the antibiotic therapy to 28 days. Similarly, a case report of erythema migrans in a patient treated with infliximab and methotrexate suggested that TNF-α blockers do not need to be discontinued if antibiotic therapy is prolonged and close follow-up is ensured [

20].

In contrast to the more typical involvement of the facial nerve in Lyme disease, our patient presented initially with a sixth nerve palsy. Such an initial presentation is uncommon and highlights both the broad spectrum of manifestations of neuroborreliosis and the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnostic when evaluating cranial nerve palsies especially in immunocompromised patients. For ophthalmologists and neurologists practicing in endemic regions, maintaining awareness of Lyme disease as a potential cause is critical. Early recognition and appropriate antibiotic therapy not only resolve acute symptoms but also prevent chronic complications.