Abstract

In the age of global challenges, digitalisation in any social system must be shaped for the common good and not for particular economic interests. In order to do so, it is incumbent upon studies of information to explicate the possibility of such a design. How can the interplay of social and technological factors be modelled to allow for digital humanism? The author proposes the model of so-called “techno-social systems”. By terming them so, they shall be differentiated from usually being called—in reverse order—“socio-technical systems”. This study shall make clear that a techno-social system is a specification of a social system and not the other way around. The shaping of such a system can then be understood by a cycle of ideal values, value dispositions and value qualities. It is this cycle that can be influenced by social actors. It can materialise digital humanism through compliance with imperatives concerning the technological support for worldwide governance, worldwide dialogue and worldwide netizenship.

1. Introduction

Global challenges have been besetting (human) social evolution in the so-called Anthropocene. These are existential threats that are, of course, mediated by technology, but technology is not the root cause—rather, the cause is social. The Atomic Age ushered in by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the degradation of the global environment since the 1960s by herbicides, pesticides and other substances nature cannot bear, and the unjust worldwide distribution of wealth are conveyed by technologies, but it is social factors that account for the mounting global challenges. In other words, the poly-crisis of today is manmade, anthropogenic, and it is up to humanity to put an end to it. Technology must not be part of the problem. Moreover, it can become part of the solution, especially if the Great Bifurcation between an integration of the diversity of interdependent social systems into a single meta-/supra-system unity that allows humans to cope with the increased complexity of the challenges and a disintegration of social systems falling back to barbarism, collapse or extinction is well understood, if the reorganisation of world society is made task number one on the agenda of humanity and if technological development is employed in this task [1].

Technology can support the objective requirements of the great transformation towards a global sustainable information society by providing tools that conform with the logic of pan-humanism, of anthropo-relational humanism and of digital humanism in all societal relations [2]. Furthermore, it can support the subjective requirements of the great transformation by helping to extend the cognitive, communicative and co-operative capabilities beyond the parochial limits to the planetary level at which humanity turns out to have become a community of destiny but is still lacking a common awareness of this situation.

However, misconceptions about the relationship between society and technology prevent practice from exploiting the technological potential for the social task set. A technodeterministic push approach or a social-constructivist pull approach hypostatise each one side of the two, while a techno/social duality is indifferent, lumping the social and the technical together [1]. How can a relationship be conceptualised that not only allows but can even boost the needful adjustments of technology development for a common future of humanity? Such a concept is possible. It can be built as an integrative approach based upon systemism.

2. The Foundation of the Model

The theoretical model of a techno-social system advocated for here is able to show the objective dynamics that allow interventions via subjective controls.

The underlying emergentist systemist comprehension rules out a mechanistic understanding as well as sociologism [3], as well as a flat ontology.

A techno-social system is not a mechanism in which causes and effects proceed in a strictly deterministic manner. Although most technologies function as such mechanisms and are not themselves systems in the sense of emergent, i.e., self-organising systems, when they are integrated into a social and thus emergent system, the integrated techno-social system exhibits a circular causality that produces emergent effects because it remains a social system even after the integration of the mechanisms. Since it is to be assumed that society shapes technology and that technology has an effect on society, according to this model, both the social shaping of technology and the social effects of the application of technology entail emergent properties that are due to the social nature of the techno-social system.

3. The Architecture of the Model

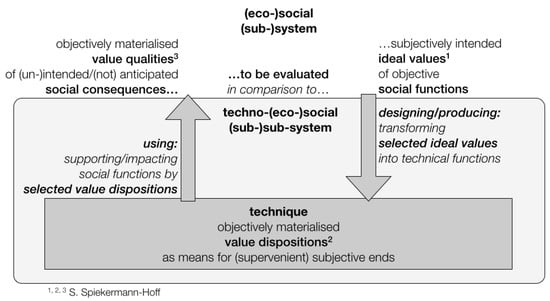

We employ a holarchy [4], a nested encapsulation of social systems (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Techno-social system. Architecture and dynamics.

There is an overall system comprising other systems as subsystems and sub-subsystems. It can be called the generic social system, which is, as a rule, society.

The next embedded system is the ecological subsystem of society, known under the title of the natural environment. It is that part of nature that has become part of society. Thus, it is justified to name it the eco-social system. This term can be referred to in the plural, i.e., eco-social systems, since these systems describe different parts of nature that play a role as part of society.

Techno-social systems are embedded in the eco-social systems. They cannot be considered without ecology. They produce and use artefacts made from nature and functionalise natural cause–effect relationships for social functions. Technology consists of artificially manufactured machines, methods and plans, the functioning of which is designed to determine further interventions in the ecology, making them more efficacious and efficient in order to yield very specific results. Technology does not constitute a self-organising system; it is a mechanistic part of a self-organised system.

As subsystems of the eco-social systems, techno-social systems are, literally, techno-eco-social systems (and sub-subsystems of the generic social system). They form the technological infrastructure of any society. For the sake of simplicity, we can abstract the techno-social relationship from its mediation via the ecology.

4. The Dynamics of the Model

Social systems, like natural systems, are characterised by self-organisation, which makes both emergent systems. Social systems are distinguished from natural systems by their property of normativity—by the indispensable role of values, norms and interests. Values are collective attributions that represent the meaningfulness of objects to subjects. Norms are collective expectations that represent demands for action while resorting to values. Interests are individual propensities to act, representing a collective attribution of rights and duties while respecting norms [1]. Actors then assume responsibility for actions through justifications in relation to values, norms and interests.

Besides the responsibility for the technical functioning that is presumed to be a matter of fact, there is clearly a social responsibility because the designed mechanism serves, willingly or not, a social function. Anybody producing or using technology needs to answer the following question: is the social function that the mechanism was designed to support exactly the social function that is really supported, or are other social functions (also or only) supported by it, and which of the intended or materialised functions are also worthy of technical support—i.e., does the mechanism promote the right values, does it conform to the right norms, and does it benefit the right interests? Does the technology work in a defensible social sense? This is then a question of morals and ethics. Values, norms and interests are moral if they refer to the good and can be described as more or less good or evil. Ethics is the reflection of morality.

With recourse to Sarah Spiekermann-Hoff’s value-based engineering—inspired by German phenomenology [5]—we distinguish three manifestations of values: ideal values, value dispositions and value qualities.

We start from ideal values that are implied by objective social functions and intended subjectively. This starting point is on the side of the social system at the border with the techno-social system. The border is crossed when ideal values have been selected to be transformed into technical functions. This transformation is the process of design/production of technology. It takes place within the techno-social system. It reaches its end point when selected ideal values have been materialised in value dispositions of technical functions. This materialisation is objective. It is located in the technology, the technical part of the techno-social system. As technology is a means for subjective ends, it is the starting point of another process back to the social system. The process starts when value dispositions have been selected to support/impact on social functions. This process is also a transformation process. It is the process of usage. It also performs within the techno-social system. It ends when selected value dispositions have been materialised in value qualities of social consequences beyond the border to the social system. These social consequences are objective consequences in the social system. They might be intended or unintended, and might have been anticipated or not.

Now, these processes in techno-social systems are processes of self-organisation carried out by actors, for which the occurrence of emergence is typical. Thus, in each of the two processes, at the end there is a transformative leap compared to the respective initial quality, which means the emergence of new properties. At the end of the first process, a supervenience of value dispositions accrues. Therefore, to start the second process, a selection is necessary to restrict possible ambiguity. At the end of the second process, value qualities emerge that have side effects, distant effects, and late effects. And here the circle closes: the objective social consequences have to be evaluated in comparison to the subjective initial ideal values and their corresponding norms and interests in order to be able to adapt the processes and start them anew.

5. Conclusions

The model of techno-social systems presented here opens up the space for responsible design and responsible use of technology in the Anthropocene. The cycle of an integrated technology assessment and technology design can implement social responsibility and the appropriate technical responsibility and engage with the change in society in the desired direction. Ethical design and value-based engineering can delegitimise the current prevailing logic of technology development. Since information technology has the potential to penetrate all other technologies, digitalisation is key to resetting technology at large as human-centred technology, following explicated imperatives of digital humanism [6]. These digital imperatives need to be respected when it comes to the ideal values of social functions, objectively facilitating the ecologisation of the relationship with the natural environment in the sense of anthropo-relationality and the humanisation of societal relationships for the entirety of humankind, as well as supporting the universalisation of the subjective human information capabilities to cognise, to communicate and to co-operate, such that survival and a good life are assured for everybody.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Hofkirchner, W. The Logic of the Third; World Scientific: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofkirchner, W. The Future of Anthroposociogenesis: Panhumanism, Anthroporelational Humanism and Digital Humanism. Proceedings 2022, 81, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, M. Evaluating Philosophies; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koestler, A. The Ghost in the Machine; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Spiekermann, S. Value-Based Engineering: A Guide to Building Ethical Technology for Humanity; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hofkirchner, W.; Kreowski, H.-J. Why Artificial Intelligence Alone Will Not Save Mankind: Digital Imperatives for Conviviality; Schroeder, M., Hofkirchner, W., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).