1. Introduction

Close to 125 million people worldwide suffer from psoriasis, a chronic, immune-mediated skin disorder. It normally uncovers erythematous, scaly plaques that differ extensively in size, shape, and structural location. Clinical measurements of disease severity have historically depended on scoring techniques such as the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). These physical scoring methods are inherently subjective, vulnerable to variation amongst and within observers, and incapable of acquiring the geographic coarseness of lesion form and distribution, regardless of their extensive use. Enhancements in medical imaging and artificial intelligence (AI), notably deep learning, have made it realistic to perform automated, objective, and repeatable lesion estimations. In dermatology, deep neural networks have shown remarkable outcomes on tasks that include classification of disease and detection and segmentation of lesions. Nevertheless, psoriasis shows exceptional challenges for automatic analysis due to its significant intra-class variability, intersecting skin states, and ambiguous lesion boundaries. These factors frequently limit the generalizability of traditional CNN-based segmentation models. To incorporate these challenges, we have proposed a Multiscale Convolutional Neural Network (MSCNN) architecture that integrates attention-driven context learning, multiresolution feature fusion, and morphological pattern extraction. The proposed system is exclusively designed to capture fine-scale lesion characteristics while sustaining universal contextual information, which authorizes high-precision segmentation and interpretable mapping of patterns that are clinically meaningful. This method may bridge the gap between reliable clinical decision support and automated image analysis in the treatment of psoriasis.

2. Background

Psoriasis is an auto immune inflammatory skin disorder with systematic implications, a detailed review is discussed by authors of [

1]. Evaluation of non invasive methods of imaging like infrared and ultrasound are used for diagno-sis and treatment of superficial skin disorder bridges the gap between the clinical examination and histopathology [

2]. Advancement in the treatment and analysis of skin disorder introduces use of machine learning and deep learning frameworks for the detection, prediction and classification of the skin diseases. Melanoma and other skin cancers have been the focus of skin lesion segmentation, which has used architectures like U-Net, Mask R-CNN, and encoder–decoder models [

3,

4]. On the other hand, there are still a few deep learning applications for psoria-sis segmentation. Earlier techniques used K-means clustering in conjunction with multiscale superpixel segmenta-tion to define lesions [

5]. Nevertheless, these methods frequently had trouble with generalization under various imaging conditions and boundary precision. To improve segmentation accuracy, recent developments have added multiscale frameworks and attention-based mechanisms. Notably, PSO-Net demonstrates enhanced lesion delinea-tion by integrating attention-guided interpretable deep neural networks for automated psoriasis assessment [

6]. Furthermore, a brand-new multiscale convolutional feature learning technique has been put forth to reliably iden-tify lesion boundaries in a range of sizes and imaging variations [

7]. To identify the specific image boundaries U-Net model is discussed which uses encoder-decoder segmentation for image segmentation [

8]. In order to distin-guish between similarity in the image features like texture, colour, a novel technique optimised global refinement demonstrated better results [

9]. The effective use of artificial intelligence in decision making clinical dermatology improves the diagnosis accuracy specifically in human and AI collaboration [

10]. Whereas the use of various trans-fer learning methods and federated learning showcases the improved results for the classification of the skin dis-ease. The methods includes the use of deep learning, machine learning frameworks for the classification of different types of skin diseases such as melanoma, psoriasis, etc. [

11,

12,

13,

14].

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset Description

The dataset used in this study is the ISIC-2017 Skin Lesion Segmentation dataset. The ISIC-2017 Skin Lesion Segmentation Dataset, initially released as part of the International Skin Imaging Collaboration’s 2017 Challenge on Skin Lesion Analysis, is a widely used reference for lesion segmentation tasks in medical image analysis. The dataset consists of a collection of diverse images that includes a variety of skin tones. A total of 2750 dermoscopic images from multiple international clinical centres are included in the collection, each with pixel-by-pixel ground truth mask annotations. The dataset is divided into three subsets: 2000 images for training, 150 images for validation, and 600 images for testing. The images depict the variety of clinical imaging in the real world, with pixel sizes ranging from 540 × 722 to almost 6700 × 4400. The dataset includes a representative range of lesion forms, such as benign nevi, seborrheic keratoses, and malignant lesions, providing a comprehensive foundation for evaluating algorithms across multiple diagnostic categories. The ISIC-2017 dataset is considered the gold standard benchmark for skin lesion segmentation due to its size, diversity, and high-quality annotations. In addition to making it challenging for algorithms to accurately define lesions with asymmetrical shapes and hazy borders, it enables a trustworthy comparison of different deep learning frameworks in controlled environments.

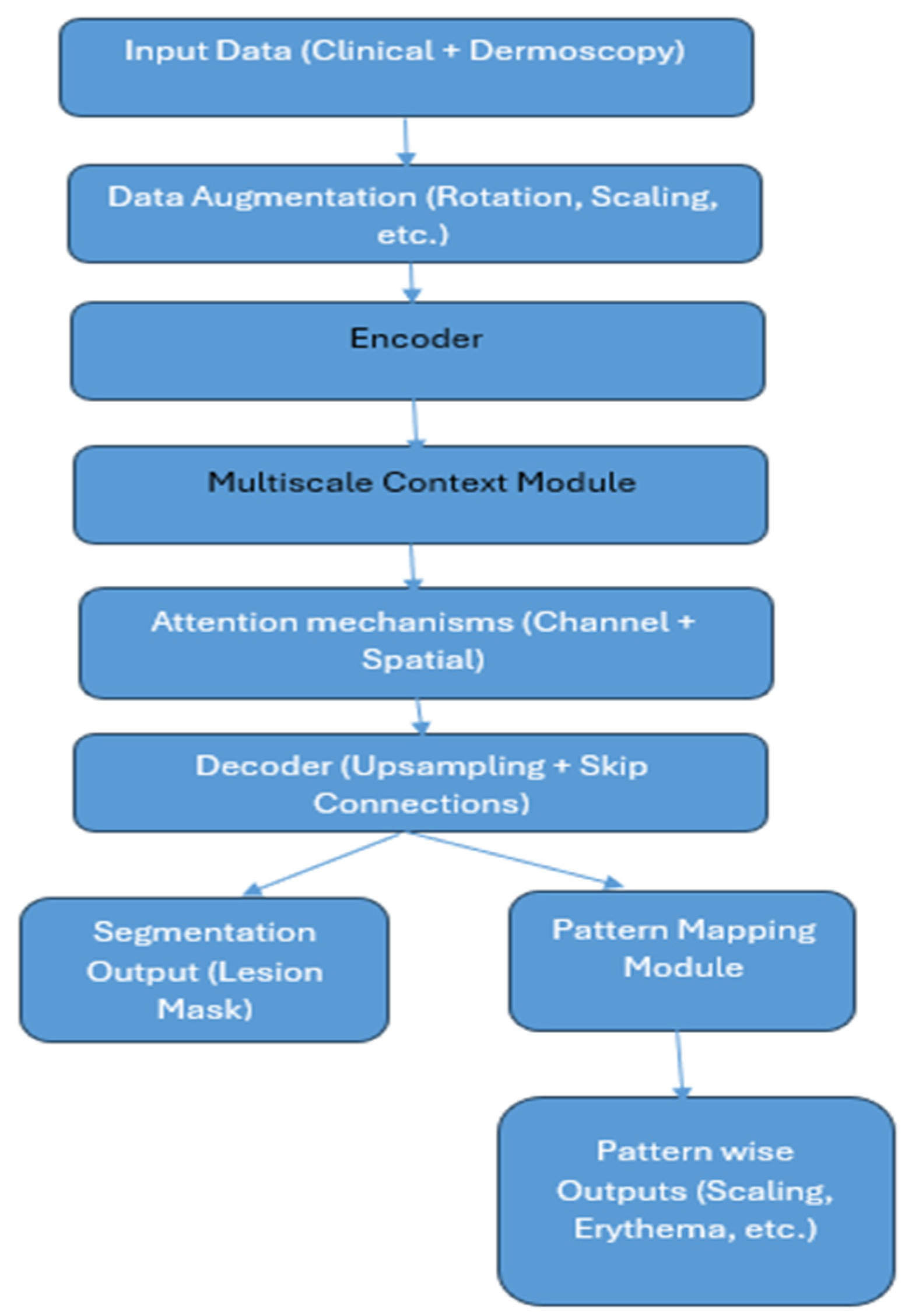

Figure 1 shows the methodology of the proposed system. The detailed working of the system is described as per the steps shown in the architecture.

3.2. Data Augmentation

The ISIC-2017 dataset, which contains dermoscopic images, has undergone a comprehensive data augmentation process to address the variability and improve model resilience. The dataset’s heterogeneity in resolution, orientation, illumination, and lesion characteristics may cause overfitting if it is trained on a small number of raw samples. This was resolved by combining geometric, photometric, and complex transformations. Geometric adjustments like random rotation, scaling, and cropping were used to account for changes in lesion orientation and size. The photometric enhancements included brightness and contrast adjustments, hue and saturation jittering, and Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE). Random affine transformations and elastic deformations were used to mimic natural variations in skin texture and lesion shape. Mix-up augmentation was applied to improve resilience against ambiguous lesion boundaries and class overlap. In addition to significantly increasing the effective training set size and exposing the network to a wide range of intra- and inter-class variations, this approach allowed for better generalization across different lesion appearances, background textures, and acquisition settings.

3.3. Encoder

The proposed MSCNN architecture extracts hierarchical patterns of skin lesion images with the help of a pretrained deep convolutional neural network backbone, ResNeXt or EfficientNet. Although dermatology datasets are fewer than those of natural world photos, this prototype employs transfer learning to attain both high-level semantic knowledge and low-level visual cues. The encoder converts the input clinical or dermoscopic image into abstract feature maps in cooperation with batch normalization, convolutional layers, and non-linear activation functions. Hierarchical features consist of low, high, and mid, which transmit contextual and semantic information. To store computation costs and sustain essential spatial information, the encoder uses stride convolutions and bottleneck residual connections. To minimize computation costs while maintaining crucial spatial information, stride convolutions and bottleneck residual connections are employed.

3.4. Multiscale Context Module

By acquiring lesion features at diverse spatial resolutions, the Multiscale Context Module in the MSCNN method tackles the issue of variable lesion sizes, forms, and textures in psoriatic images. To expand the receptive field deprived of sacrificing resolution, this module commissions the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) method. The module captures fine-grained local information and obtains a global lesion framework using parallel atrous convolutions with dilation rates. The outputs are merged and delivered through a 1 × 1 convolution layer for stability. A global average pooling branch attains the whole lesion context, which is merged with atrous characteristics to improve global–local consistency. The Multiscale Context Module enables the MSCNN to manage lesions of different sizes, classify between skin with and without lesions, and upgrade generalization around a range of imaging modalities. Conventional CNNs’ limited kernel sizes limit their capability to capture both fine textures and broad contextual patterns. The ASPP-based multiscale module of the MSCNN explicitly incorporates multi-resolution features in correspondence to accomplish both global lesion understanding and border precision.

3.5. Attention Mechanisms

The attention segment of Multiscale CNN (MSCNN) is an essential part for precise segmentation and understandable pattern mapping in psoriatic lesions. It merges two types of attention: channel attention, which appoints weights to feature channels, and spatial attention, which represents attention to the image’s most remarkable lesion locations. Channel attention appoints weights to semantic features like redness, scaling textures, and hyperkeratotic regions to guarantee lesion discrimination. However, spatial attention aggregates information from multiple channels, merges it, and applies a convolutional layer and activation function as a sigmoid function to produce a spatial attention map that ignores background skin and focuses on specific lesion boundaries and active morphological areas. This dual-level refinement decreases false positives and improves segmentation accuracy in complex cases with overlapping or blurred lesion borders. MSCNN distinguishes itself from conventional U-Net and CNN models with the use of attention-driven refinement, which results in sharper boundaries, competent intra-lesional pattern recognition, and fostered robustness across datasets.

3.6. Decoder

The decoder uses the compressed feature embeddings from the encoder to reconstruct high-resolution lesion masks. Its main purpose is to gradually restore fine spatial details using both low-level and high-level features.

3.6.1. Staged Upsampling

The decoder uses bilinear interpolation or transposed convolutions to gradually increase the spatial resolution of the encoded feature maps. At each stage, the upsampled features are refined using convolutional layers to reduce artefacts and restore important spatial structure. This ensures that the lesion boundaries, which are often blurry in psoriasis, become clearer at each step of decoding.

3.6.2. Skip Connections

Skip connections connect encoder layers with matching decoder layers to avoid losing fine-grained information during encoding. In addition to the high-level semantic features from the encoder, these connections offer low-level spatial features (such as edges, textures, and color gradients). The decoder can recover lesion margins, subtle scaling textures, and erythema variations with high fidelity thanks to the combination of these feature sets.

3.6.3. Feature Fusion

Convolutional refinement layers combine the complementary data from the encoder and decoder pathways after concatenation. By guaranteeing both global context (important for lesion extent) and local texture detail (important for scaling), this fusion improves morphological representation.

3.6.4. Output Mapping

Finally, a segmentation mask with the same resolution as the input image is produced by the decoder. This mask minimizes leakage into healthy skin while highlighting exact lesion boundaries. Furthermore, intra-lesional classification of morphological attributes is made possible by the decoder output feeding into the Pattern Mapping Module.

3.7. Segmentation Output

The MSCNN framework’s last step generates a segmentation output mask that shows the psoriatic lesions’ pixel-by-pixel delineation. The output goes through a final 1 × 1 convolution layer after the decoder has gradually upsampled and fused multiscale features. This is followed by a softmax (for multi-class) or sigmoid (for binary) activation. For every pixel, this mapping converts the high-dimensional feature space into a probability distribution across classes. Each pixel is given a class label (such as lesion vs. non-lesion or intra-lesional patterns like scaling, erythema, and hyperkeratosis) in the resulting binary or multi-class lesion mask.

This mask offers accurate boundary delineation that captures the psoriasis’s characteristic, irregular, hazy margins. Segmentation that is spatially consistent and has fewer false positives because of attention-driven refinement. Clinical interpretability, since the mask emphasizes the size and shape of the lesion in a manner consistent with the visual evaluations of dermatologists.

Sharper lesion margins and less over-segmentation into surrounding healthy skin are ensured by refining the output using the boundary-aware loss function to further improve contour quality. Both automated PASI scoring and in-depth clinical analysis are supported by this pixel-accurate lesion mask, which serves as the foundation for objective quantification of lesion area, severity, and intra-lesional patterns.

3.8. Pattern Mapping Module

A new method for evaluating psoriasis, the MSCNN framework, focuses on identifying intra-lesional morphological patterns like scaling, erythema, and hyperkeratosis. A Pattern Mapping Module that runs concurrently with the primary segmentation decoder is integrated to accomplish this. The module includes extracting input and patches, using a lightweight CNN to process each patch, and combining CNN features with manually created descriptors. Following the fused feature vectors’ passage through fully connected layers and a softmax classifier, each patch is assigned to one of several categories, including Background, Erythema, Scaling, or Hyperkeratosis. After that, a pattern map overlaying intra-lesional attributes on the segmented lesion is created by re-projecting the classified patches onto the lesion mask. Dermatologists can gain fine spatial insights beyond just the lesion area by using the pattern map, which offers interpretable visualizations of psoriasis morphology. This improves traditional scoring methods by permitting the objective quantification of severity factors. By concatenating morphological distribution (from pattern mapping) and lesion extent (from segmentation), the proposed system facilitates automated, clinically significant PASI estimation. Given that conventional segmentation networks end at lesion border detection, this is a key step towards explainable AI in dermatology.

3.9. Pattern-Wise Outputs

One tool that highlights unique morphological patterns within psoriatic lesions is the Pattern Mapping Module, which produces outputs at the pixel and patch levels. Clinicians can view important pathological characteristics like scaling, erythema, hyperkeratosis, background, and non-lesional skin in a spatially resolved manner thanks to these outputs. Erythema outputs show red patches that indicate inflammatory activity, while scaling outputs show white or silvery scales on the lesion surface. The outputs of hyperkeratosis show areas of aberrant epidermal thickening, which aid in determining how a disease progresses and how well a treatment works. To avoid false positives, the module separates lesion-free areas and makes sure that lesion patterns are cleanly separated from healthy skin. Each pattern is color-coded and superimposed as a multi-class mask. Dermatologists can visually examine the spatial distribution of each morphological component thanks to the resulting interpretable lesion atlas. Explainability and objective, repeatable PASI estimation are made possible by pattern-wise outputs, which take the place of human scoring, which is subjective. They are especially useful in longitudinal tracking, which allows for the monitoring of changes in thickness, erythema, and scaling over time to assess the efficacy of therapy.

4. Experimental Results

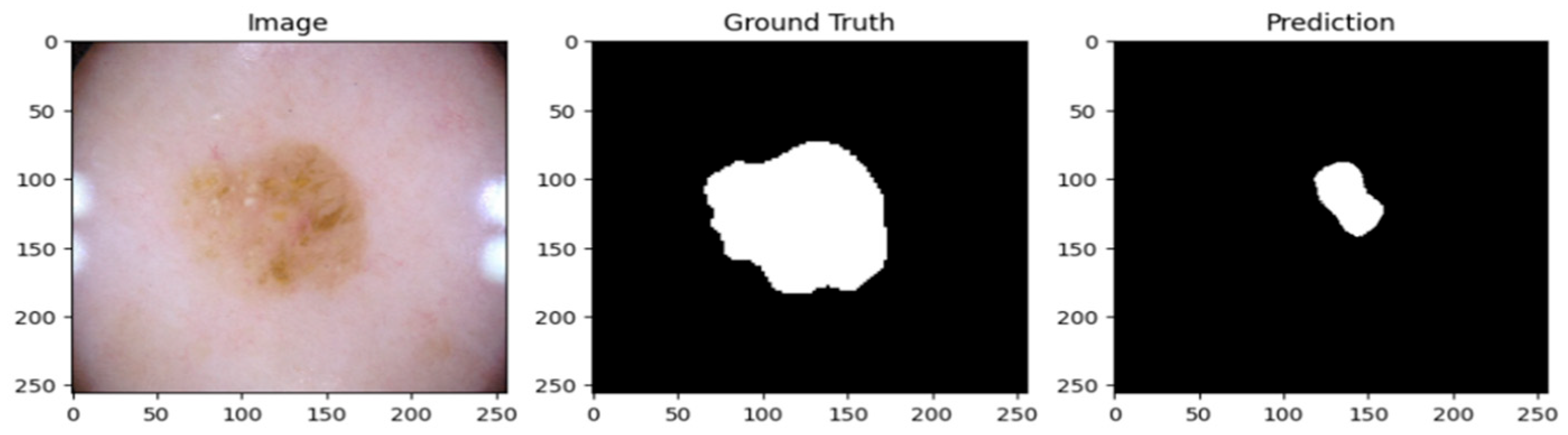

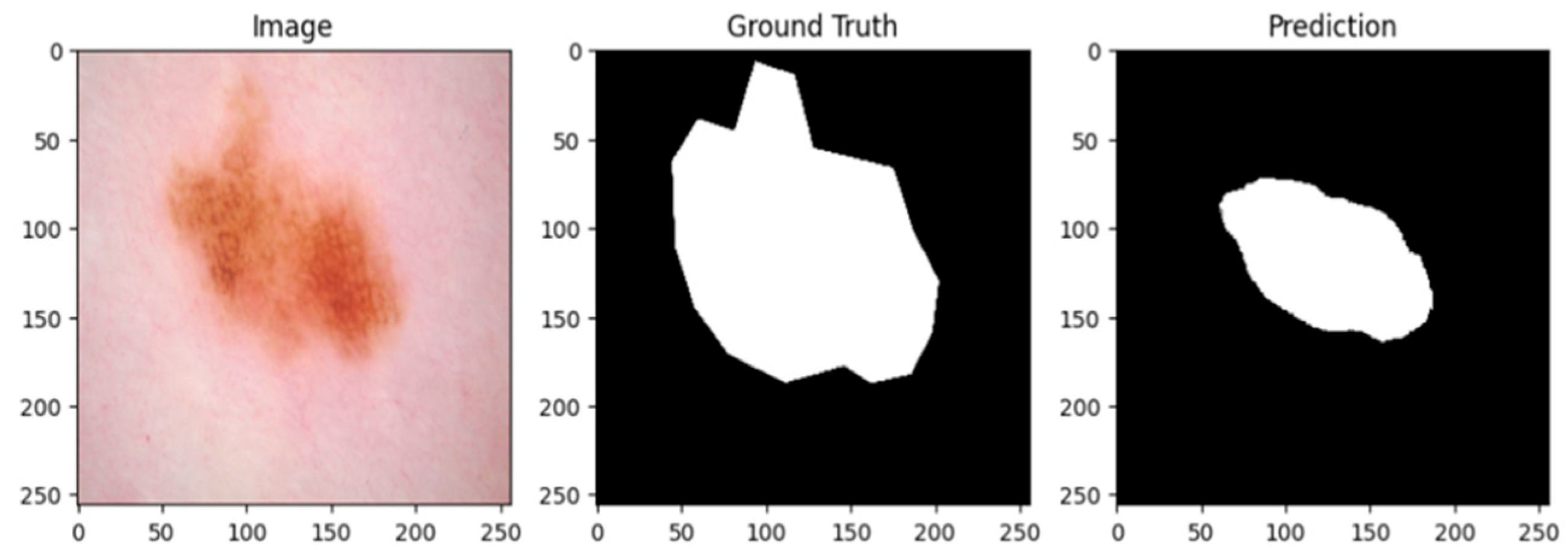

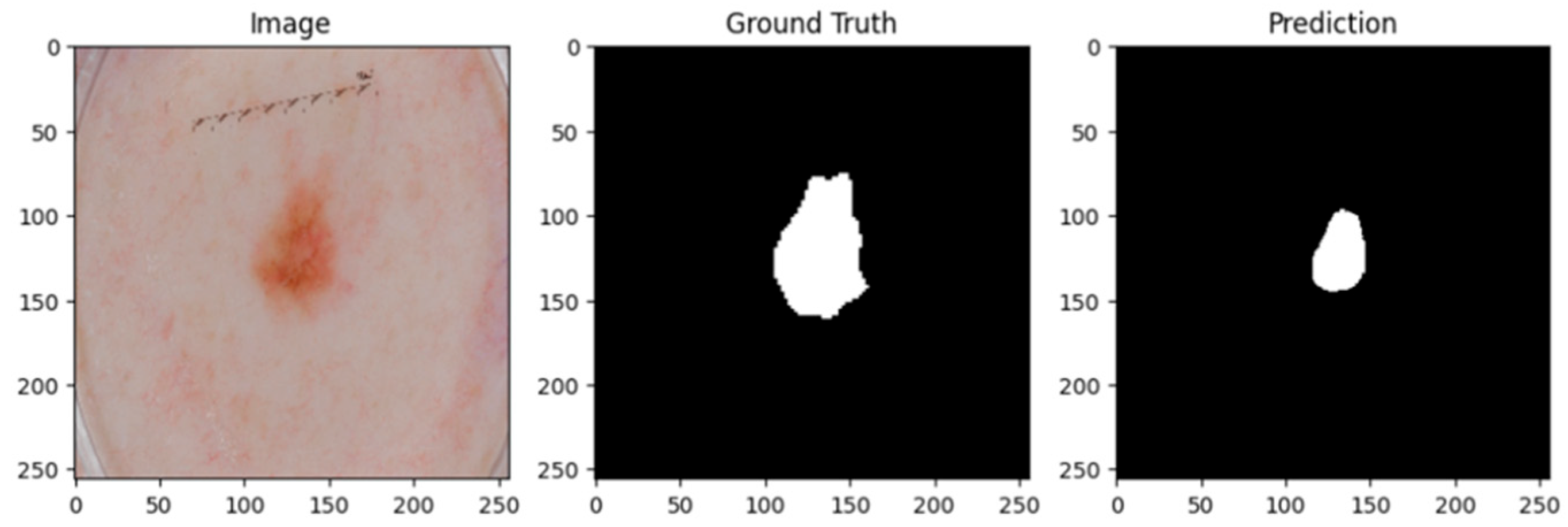

A psoriatic lesion dataset from the ISIC 2017 skin segmentation dataset was used to assess the suggested Multiscale Convolutional Neural Network (MSCNN). Using clinical images, the framework successfully produced lesion masks. When examining the predicted masks, it is evident that the model correctly identified the location of psoriatic lesions, with boundary delineations that closely matched the annotations found in the ground truth.

A cautious approach to boundary detection is demonstrated in the first example, where the model successfully captured the lesion core but marginally un-der-segmented the surrounding areas.

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the lesion masks predicted by the model. Although there were still some slight variations at the lesion margins, the second example showed improved overlap with the annotated mask, whereas the third model showed an improved version of prediction over the first and second models. This shows that although lesion-specific features have been successfully learnt by the model, boundary refinement still needs work.

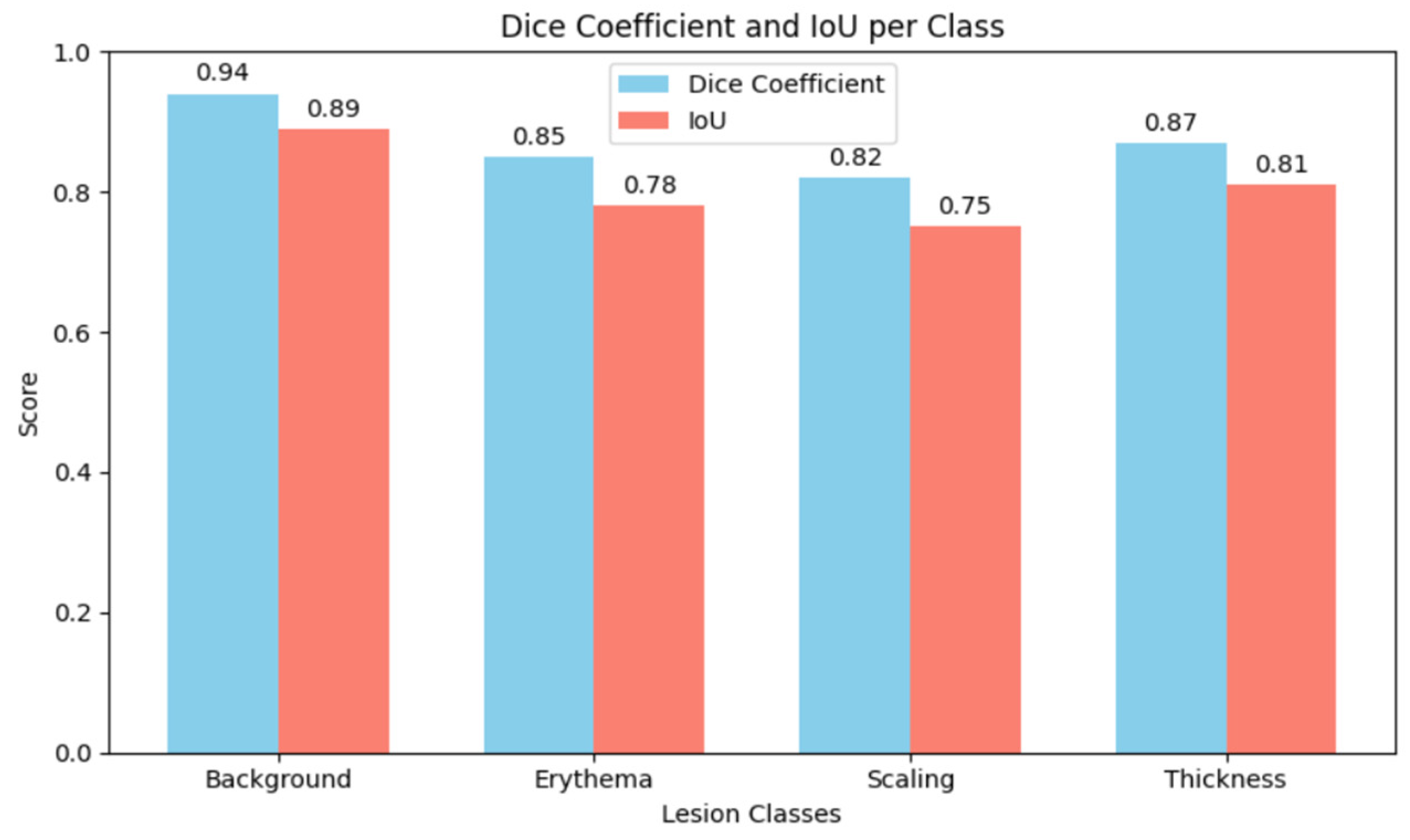

Figure 5 shows the comparative analysis of dice coefficient & intersection over union score with re-spect to background, erythema, scaling & thickness.

The Dice Coefficient, Intersection over Union (IoU), precision, and recall were used to assess the model’s performance. Although sensitivity in detecting fine-scale irregulari-ties along lesion borders was somewhat diminished, the results show that the MSCNN achieves robust overall lesion localization. While recall was marginally lower, reflect-ing sporadic under-segmentation of lesions, precision stayed continuously high, sug-gesting a low rate of false positives.

5. Conclusions

Multiscale context encoding, skip connections, and resilience to changes in lesion size, shape, and intensity are some of the advantages of the multi-class pattern mapping framework. However, it does not distinguish between clinically significant psoriatic patterns such as erythema, scaling, or thickness, and it is restricted to binary lesion segmentation. In certain instances, the conservative predictions may underestimate the extent of the lesion. There are not many dataset annotations, and more research is needed to confirm the model’s generalizability across a range of skin tones and imaging conditions. More annotated datasets are required to expand this framework, or labels from texture and color variations could be approximated using self-supervised or weakly supervised techniques. Lesion boundary detection and pattern differentiation may be further improved by incorporating transformer-based encoders and attention mechanisms.