Systematic Review of AI-Driven Personalization in Serious Games for Teaching at the Right Level in Morocco †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

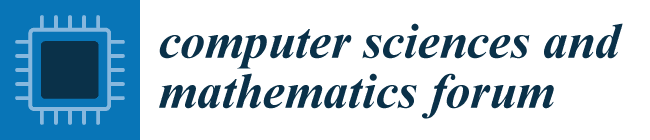

- (1)

- Tailoring the assessment design to fit the Moroccan primary education context;

- (2)

- Developing an educator dashboard for monitoring and control;

- (3)

- Ensuring real-time adaptivity based on student levels and performance;

- (4)

- Incorporating gamification to sustain learner engagement.

3. Results

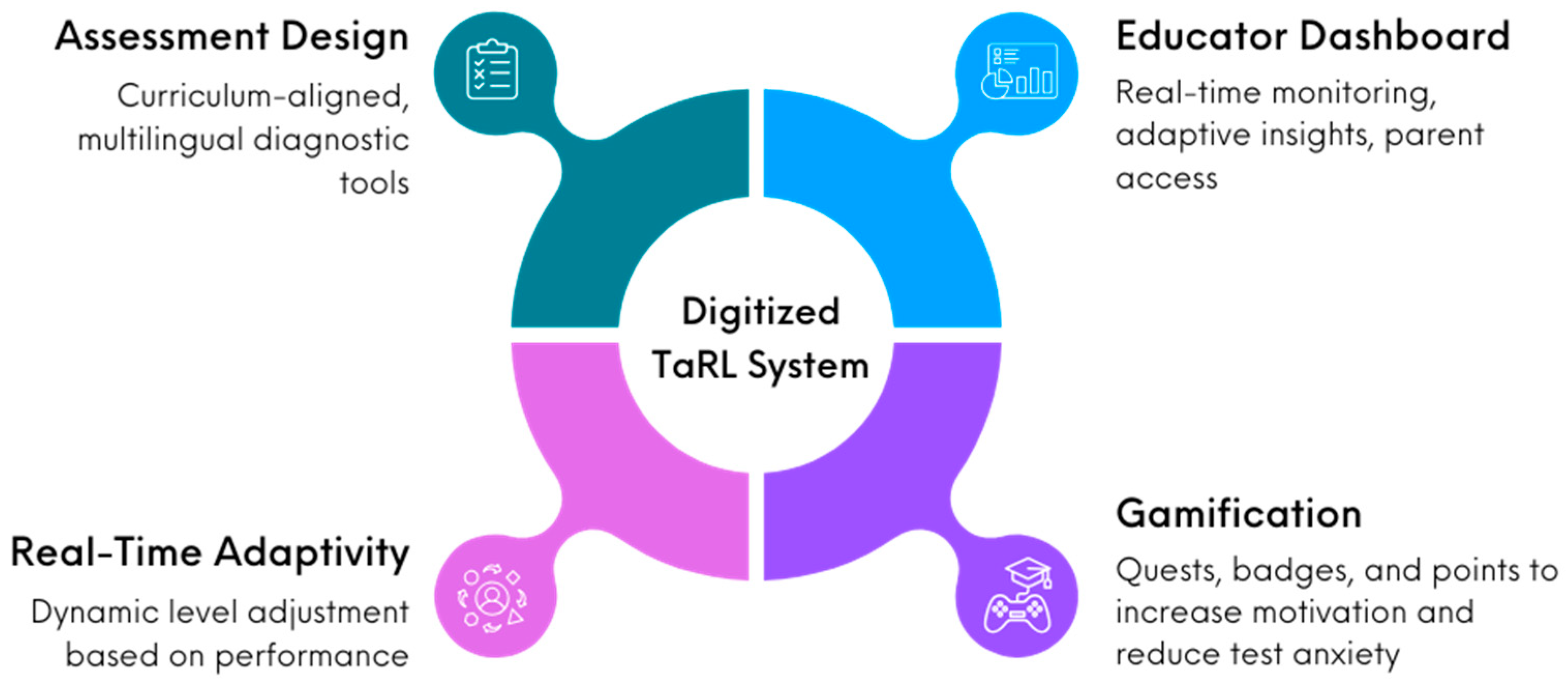

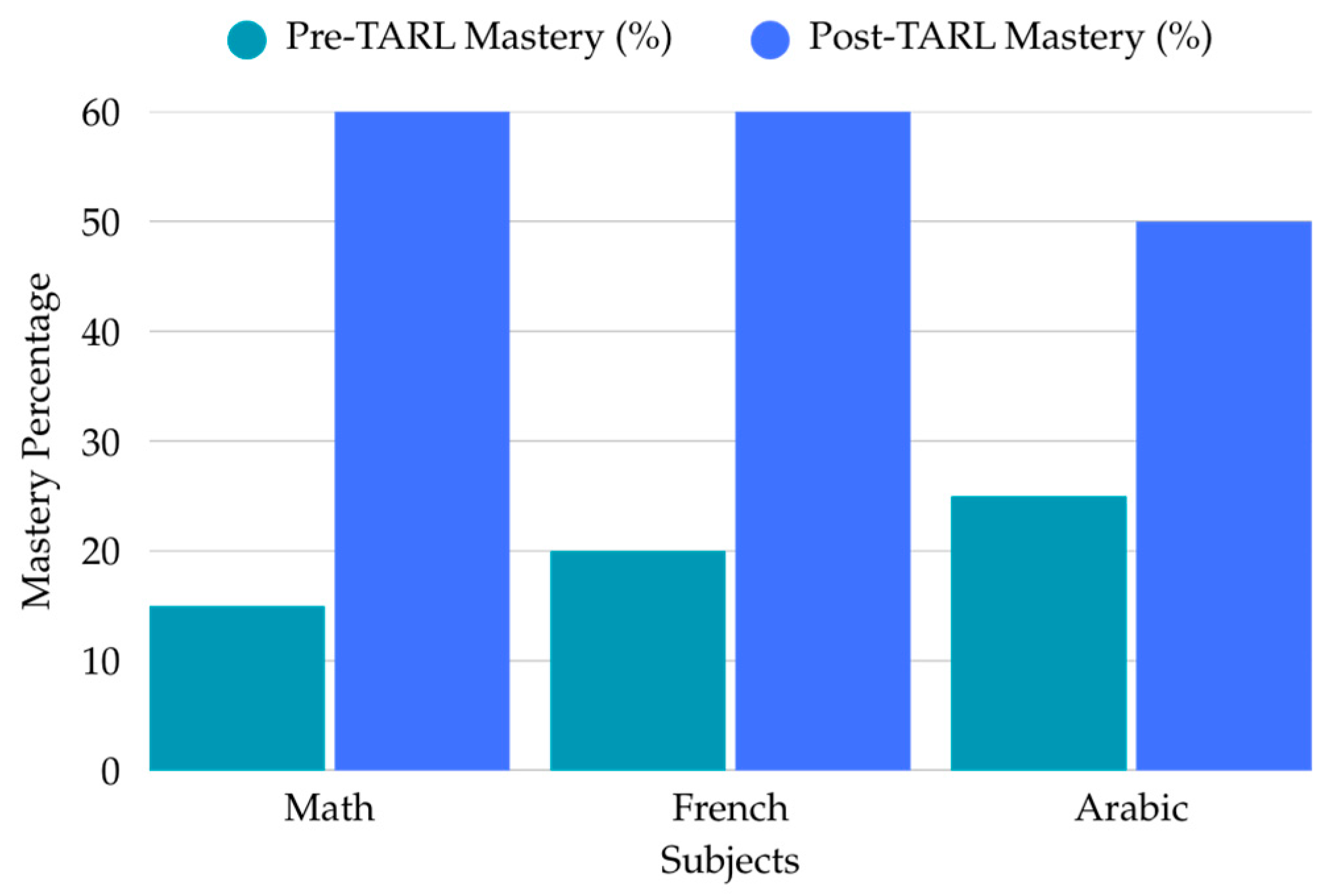

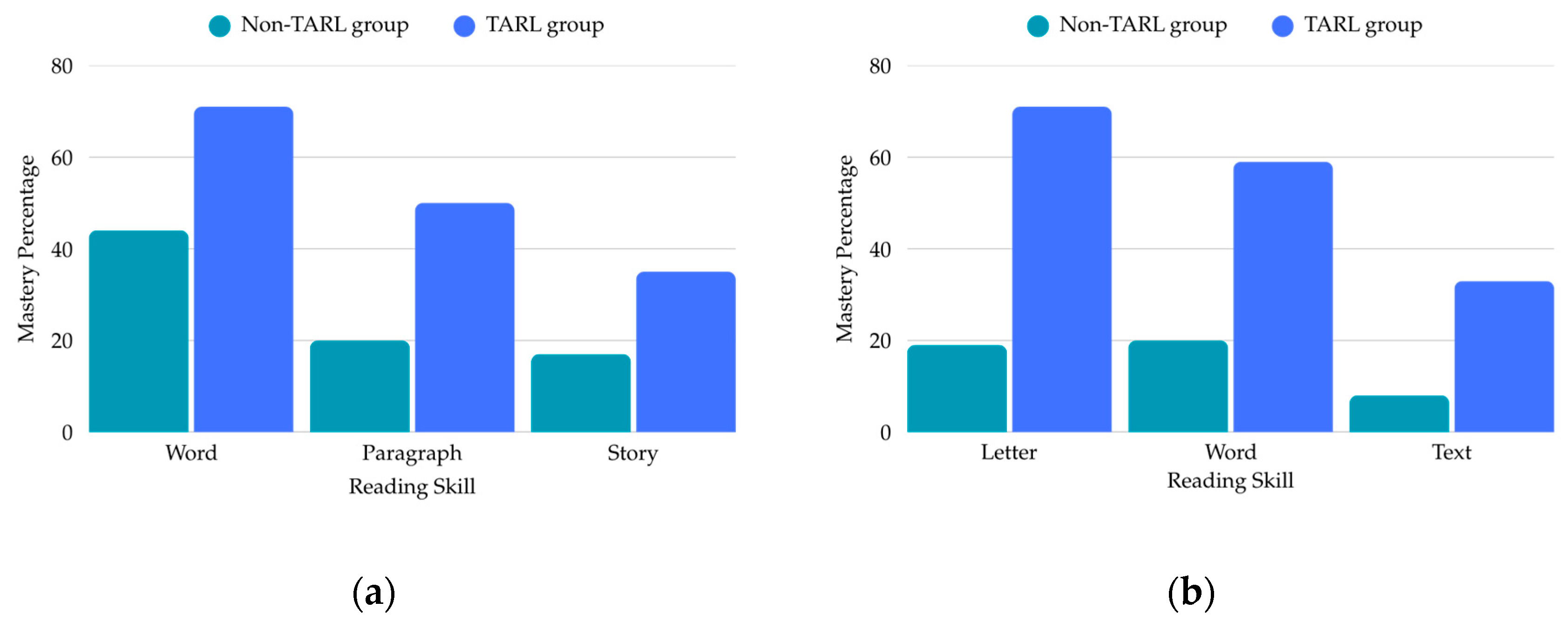

3.1. Statistical Evaluation of TaRL-Based Remediation Outcomes

3.2. Review and Comparative Analysis of Digital Tools Aligned with DM-TaRL Principles

3.2.1. Overview of Digital Tools Supporting DM-TaRL Approach

3.2.2. Comparative Evaluation Against Popular Educational Platforms

3.3. Simulated Use Case

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DM-TaRL | Digitized Moroccan Teaching at the Right Level |

| TaRL | Teaching at the Right Level |

| LMS | Learning management system |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| CNRST | Centre National pour la Recherche Scientifique et Technique |

| FSTT | Faculty of Sciences and Technologies of Tangier |

| C3S | Computer Science and Smart Systems |

References

- Yabiladi.com. Post-COVID-19: The World Bank Calls for a «More Solid» Moroccan Educational System. Available online: https://en.yabiladi.com/articles/details/101046/post-covid-19-world-bank-calls-more.html (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- UNESCO. Addressing Students’ Learning Gaps to Ensure Quality Learning for All Children and Prevent Drop-Out in Asia-Pacific. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/addressing-students-learning-gaps-ensure-quality-learning-all-children-and-prevent-drop-out-asia (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Masaiti, A.E. Morocco to Adopt India’s Teaching at the Right Level Educational System. HESPRESS English—Morocco News. Available online: https://en.hespress.com/50958-morocco-to-adopt-indias-teaching-at-the-right-level-educational-system.html (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Ismail, I.A.; Qadhafi; Jhora, F.U.; Yorinda, A. Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) as a Potential Solution for Improving Middle School Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Acad. Pedagog. Res. 2024, 8, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazuli, L. Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) Through the All Smart Children Approach (SAC) Improves Student’S Literature Ability. Prog. Pendidik. 2024, 3, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratham. Teaching at the Right Level. Available online: https://www.pratham.org/about/teaching-at-the-right-level/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- TaRL Africa Teaching at the Right Level—Africa. Available online: https://teachingattherightlevel.org/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Binaoui, A.; Moubtassime, M.; Belfakir, L. The Effectiveness of the TaRL Approach on Moroccan Pupils’ Mathematics, Arabic, and French Reading Competencies. Int. J. Educ. Manag. Eng. 2023, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdi, O.; Belamhitou, M.M. The Teaching at the Right Level approach: A paradigm shift to accelerate Moroccan pupil’s learning. Afr. Educ. Res. J. 2024, 12, 238–254. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-H.; Tzeng, G.-H. Creating the aspired intelligent assessment systems for teaching materials. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 12168–12179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, D.; Inman, S.; Ding, Z.; Kang, Y.; Kuna, P.; Liu, Y.; Lu, X.; Oro, S.; Wang, Y. Improving Teacher Effectiveness: Designing Better Assessment Tools in Learning Management Systems. Future Internet 2015, 7, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edson, A.J.; Phillips, E.D. Connecting a teacher dashboard to a student digital collaborative environment: Supporting teacher enactment of problem-based mathematics curriculum. ZDM Math. Educ. 2021, 53, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, I.; Knoop-van Campen, C. Teacher Dashboards in Practice: Usage and Impact. In Proceedings of the Data Driven Approaches in Digital Education; Lavoué, É., Drachsler, H., Verbert, K., Broisin, J., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Cultura, S.; Sharma, K.; Giannakos, M.N. Multimodal Teacher Dashboards: Challenges and Opportunities of Enhancing Teacher Insights Through a Case Study. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoop-van Campen, C.; Molenaar, I. How Teachers Integrate Dashboards into Their Feedback Practices. Frontline Learn. Res. 2020, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B. Digital education governance: Data visualization, predictive analytics, and ‘real-time’ policy instruments. J. Educ. Policy 2016, 31, 123–141. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02680939.2015.1035758 (accessed on 21 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Moltudal, S.H.; Krumsvik, R.J.; Høydal, K.L. Adaptive Learning Technology in Primary Education: Implications for Professional Teacher Knowledge and Classroom Management. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 830536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.S.; Renumol, V.G. An improved adaptive learning path recommendation model driven by real-time learning analytics. J. Comput. Educ. 2024, 11, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debeer, D.; Vanbecelaere, S.; Noortgate, W.V.D.; Reynvoet, B.; Depaepe, F. The effect of adaptivity in digital learning technologies. Modelling learning efficiency using data from an educational game. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1881–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannier, N.; Hudson, S.E.; Chang, H.; Koedinger, K.R. AI Adaptivity in a Mixed-Reality System Improves Learning. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 34, 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, G.C.A.; Barraqui, L.P.; de Freitas, S.A.A. Evaluating the use of gamification in mathematics learning in primary school children. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), San Jose, CA, USA, 3–6 October 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloluwa, T.; Vyas, D.; Usoof, H.; Hewagamage, K.P. Gamification for development: A case of collaborative learning in Sri Lankan primary schools. Pers. Ubiquit. Comput. 2018, 22, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgieri, R.; Vanutelli, M.E.; Galbiati, P.D.V.; Lucchiari, C. Gamification and Coding to Engage Primary School Students in Learning Mathematics: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, 2–4 May 2019; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arufe-Giráldez, V.; Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A.; Ramos-Álvarez, O.; Navarro-Patón, R. Gamification in Physical Education: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitra, K.; Konstantinos, K.; Christina, Z.; Katerina, T. Types of Game-Based Learning in Education: A Brief State of the Art and the Implementation in Greece. Eur. Educ. Res. 2020, 3, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Vrcelj, A.; Hoic-Božic, N.; Dlab, M.H. Use of Gamification in Primary and Secondary Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 2023, 9, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiuza-Fernández, A.; Lomba-Portela, L.; Soto-Carballo, J.; Pino-Juste, M.R. Study of the knowledge about gamification of degree in primary education students. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Participatory Educational Research» Submission» The Views and Adoption Levels of Primary School Teachers on Gamification, Problems and Possible Solutions. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/per/issue/54375/713777 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Pratham Books. StoryWeaver. StoryWeaver Has Been Recognised as a Digital Public Good for Foundational Literacy and Early-Grade Reading! Available online: https://storyweaver.org.in (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Piper, B.; Destefano, J.; Kinyanjui, E.M.; Ong’ele, S. Scaling up successfully: Lessons from Kenya’s Tusome national literacy program. J. Educ. Chang. 2018, 19, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solve Education! Dawn of Civilization—Play and Learn English! Dawn of Civilization. Available online: https://dawnofcivilization.net/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Solve Education! Technology—ED THE LEARNING BOT. Available online: https://solveeducation.org/technology/ed-the-learning-bot/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Fuadah, N.T. Solve Education! Supporting Indonesia’s Educational Transformation at GSVI 2024. Solve Education! Available online: https://solveeducation.org/solve-education-supporting-indonesias-educational-transformation-at-gsvi-2024/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Solve Education! Solve Education! Annual Progress Report 2022. 2022. Available online: https://solveeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/Annual_Progress_Report_2022.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

| Country | Tools/Platforms | Modality | Outcomes | DM-TaRL Pillars Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | StoryWeaver, Read Along | Mobile digital library and speech-based reading app | Early literacy gains | Gamification, Real-Time Adaptivity |

| Kenya | Tusome Digital | Tablet-based assessments and teacher dashboards | Early literacy gains | Assessment Design, Educator Dashboard |

| Indonesia | Dawn of Civilization, Ed the Learning Bot | Gamified mobile learning app and AI-powered chatbot | Enhanced foundational skills | Gamification, Real-Time Adaptivity |

| Platform/Method | Strengths | Limitations | Comparison with DM-TaRL |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaRL | Effective in grouping by learning level | High teacher workload; manual performance tracking | DM-TaRL automates diagnostics and reduces teacher burden |

| Squirrel AI | Strong personalization | Limited cultural relevance; minimal teacher involvement | DM-TaRL includes dashboards and localized content |

| Khan Academy | Excellent foundational content | Lacks real-time adaptivity | DM-TaRL adds dynamic level adjustment |

| DreamBox Learning | Adaptive and gamified | Weak teacher integration | DM-TaRL embeds teacher feedback and local alignment |

| Mindspark | Adaptive, multilingual, and evidence-based | Minimal gamification; requires supervised usage for impact | DM-TaRL adds gamification and real-time dashboards |

| Step | Process | System’s Role | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Student Profile | 10-year-old student from rural Morocco with arithmetic difficulties | Uses initial profile to generate diagnostic test and learning plan | Early detection of gaps for personalized instruction |

| 2. Diagnostic Assessment | Student completes a short game-based test | Places student in a skill-appropriate group | Accurate level placement and targeted support |

| 3. Personalized Pathway | Student works through tailored activities | Adjusts tasks based on mastery and engagement | Confidence-building and gradual skill mastery |

| 4. Gamified Progression | Student earns rewards for milestones | Provides badges, visuals, and game-like tracking | Motivation sustained through interactive feedback |

| 5. Real-Time Teacher Monitoring | Teacher tracks progress live | Flags struggling areas and suggests instructional strategies | Timely interventions improve learning trajectory |

| 6. Adaptive Learning Loop | Student continues through evolving tasks. | Reassesses periodically to refine path | Measurable progress in literacy and numeracy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abarghache, N.; Soulimani, Y.A.; Elaachak, L.; Ghadi, A. Systematic Review of AI-Driven Personalization in Serious Games for Teaching at the Right Level in Morocco. Comput. Sci. Math. Forum 2025, 10, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2025010003

Abarghache N, Soulimani YA, Elaachak L, Ghadi A. Systematic Review of AI-Driven Personalization in Serious Games for Teaching at the Right Level in Morocco. Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum. 2025; 10(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2025010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbarghache, Najlae, Younès Alaoui Soulimani, Lotfi Elaachak, and Abderrahim Ghadi. 2025. "Systematic Review of AI-Driven Personalization in Serious Games for Teaching at the Right Level in Morocco" Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum 10, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2025010003

APA StyleAbarghache, N., Soulimani, Y. A., Elaachak, L., & Ghadi, A. (2025). Systematic Review of AI-Driven Personalization in Serious Games for Teaching at the Right Level in Morocco. Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum, 10(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2025010003