Abstract

Purpose: Ankyloglossia or tongue-tie (TT) occurs when the lingual frenulum is visually altered and accompanied by restricted tongue mobility causing feeding and other difficulties for infants. Pre- and post-operative stimulation techniques are known to be effective in preventing tissue reattachment and ensuring feeding success. The aim of this study was to gather feedback from parents and health professionals for an experimental evidence-based pre- and post-operative care protocol for breastfeeding infants undergoing surgical management for TT. Methods: A qualitative approach was used to evaluate an experimental pre- and post-operative care protocol for infants with TT, through virtual semi-structured interviews with clinicians and parents of children with TT. Five parents and eight current practicing clinicians were interviewed to obtain feedback on the protocol in development. The results were analyzed using thematic analysis. Results: Four themes were generated from participants: (1) parental confidence and competence, (2) the need for individualized and adaptable instruction; (3) supporting the parent and infant equally; and (4) regular and periodic support and adjustment to protocol. Conclusions: The findings from the qualitative interviews highlighted the importance of fostering parental confidence and education, adaptability and flexibility in care, and clinician reassurance throughout the process. The participants suggested these factors would contribute to greater adherence to care protocols and improved outcomes for both infants and their families. This research emphasizes the importance of providing care that extends beyond logistics of oral stimulation techniques and instead recommends a mindful, family-centered approach that empowers and motivates families throughout the process.

1. Introduction

Ankyloglossia, or tongue-tie (TT), is a congenital condition of the oral cavity where an unusually short and tight lingual frenulum restricts tongue mobility and function [1]. For infants under twelve months, TT is commonly associated with bottle and breastfeeding difficulties, such as an ineffective latch, nipple pain, mastitis, and poor weight gain due to ineffective sucking and swallowing functions [1]. TT is reported in 7% to 10% of infants, depending on the specificity of diagnostic criteria [2,3]. The consensus statement by the Australian Dental Association (ADA) in 2020 proposes a recommended management pathway for TT, with non-surgical management as a first-line approach, followed by surgical options if initial interventions prove ineffective [4]. Non-surgical options include positioning and lactation training, feeding therapy, stretching, and lingual massage [5,6]. Surgical interventions to improve tongue mobility and function include frenotomy (incision or lasering of the frenulum), frenectomy (removal of the frenulum), or frenuloplasty (complete release of frenulum) [7]. However, the statement lacks recommendations for pre- and post-operative care and fails to consider the perspectives and needs of parents, who directly implement the stimulation techniques.

Anecdotal evidence recognizes that pre- and post-operative care support symptom resolution and may prevent the re-attachment of the restrictive tie following the surgical intervention [8]. However, there is a significant lack of agreement, consistency, and high-quality evidence regarding stimulation techniques being used in clinical practice [4]. There are currently no universally accepted pre- and/or post-operative care protocols consistently adhered to by clinicians working with infants and children with TT. Additionally, there is no evidence regarding parent opinions of factors that would support the adherence and successful implementation of pre- and post-operative care. Pre-operative care includes lingual stimulation techniques, myofunctional therapy, and lactation or breastfeeding support [9,10,11]. Post-operative care for infants includes the continuation of lingual stimulation and stretching, wound management (antiseptic, gauze, or analgesics application), follow-up breastfeeding sessions, a recommended diet, and oral hygiene care [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Several studies have explored various pre- and post-operative care methods, including the frequency, dosage, and duration of their administration. However, many lack control variables and reliable measures to compare the effectiveness of different stimulation techniques. This results in limited high-quality evidence to determine the most appropriate care regime [13].

Research has shown that parent involvement in pre- and post-operative care is associated with improved functional outcomes following TT surgery [12,13,18]. Therefore, understanding parent perspectives of fundamental components of an effective pre- and post-operative care protocol is essential for clinicians and parents alike. Parents are key stakeholders in the implementation of care protocols for their children undergoing surgical management for TT. Quality support from caregivers can and does directly contribute to optimal clinical outcomes and the restoration of breastfeeding function. To address the current gap, the overarching aim of this study was to gather opinions and feedback from parents and clinicians regarding the experimental pre- and post-operative care protocol for infants with tongue-tie.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC2024-0106, Approval Date: 12 March 2024). This study employed a qualitative Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach and used individual semi-structured interviews to explore the feedback and opinions from parents and clinicians regarding the experimental evidence-based pre- and post-operative care protocols. Individual interviews were chosen to facilitate an in-depth exploration of participants’ perspectives, experiences, and opinions on the protocols [19]. PAR aims to gather and analyze data to “take action and make a change” and prioritizes experiential knowledge to generate practical information that has value for practice in a collaborative, cyclical process of reflection, action, and change [20]. By involving clinicians, who guide and oversee these practices, and parents, who directly experience the challenges of implementing aftercare, PAR ensured the feedback regarding pre- and post-operative care was relevant, realistic, and responsive to those most affected [21]. Individual interviews and a PAR approach ensured that feedback on the protocol was grounded in practical knowledge and real-world experiences, enhancing the potential for successful implementation and improving outcomes for parents and clinicians involved in tongue-tie aftercare [21].

In qualitative research, trustworthiness is established through credibility, transferability, dependability, and reflexivity [22]. To enhance credibility, we used a structured interview guide, purposive sampling, and data saturation to ensure comprehensive and relevant data collection. Multiple researchers participated in coding to verify findings and minimize bias. Transferability was addressed by recruiting a diverse sample of clinicians with different roles and experiences, ensuring that diverse perspectives were captured. To ensure dependability, a consistent interview guide was used, and coding was conducted by different researcher pairs, with discrepancies resolved through consensus. Regarding reflexivity and objectivity, we have included a reflexivity statement and employed NVivo version 14 software to enhance transparency. Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis framework was followed to ensure a rigorous coding process [23]. These measures strengthen the methodological rigor of our study.

2.1. Participants

A total of 13 participants were recruited for the qualitative interviews, including five parents from a local tongue-tie community advisory group. Additionally, eight clinicians were recruited, comprising one pediatric dentist, one general dentist, two International Board-Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLCs), and four Speech–Language Pathologists (SLPs). A summary of the participant demographics is shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Health professionals were recruited online and from various face-to-face conferences as outlined in Table 3. Individual semi-structured virtual interviews were conducted with both groups to gather formative feedback on the protocol and clinician-user perspectives.

Table 1.

Demographics of clinician participants.

Table 2.

Demographics of caregiver participants.

Table 3.

Distribution locations of study infographic and recruitment survey QR code for health professionals.

2.2. Materials

Materials included: experimental pre- and post-operative care protocols, Microsoft Teams for conducting virtual interviews, Microsoft Stream for automatic transcription generation, Microsoft Word for the cross-checking of interview transcripts, and NVivo14 for data analysis, coding, and theme generation [24,25,26,27,28].

Experimental Pre- and Post-Operative Care Protocol

The experimental pre- and post-operative care protocol used in this study was developed in response to the substantial variability identified in existing care regimens for infants and children undergoing frenotomy. Drawing on the findings of the systematic review by Smart, Grant, and Tseng [24], the experimental protocol aimed to provide a structured yet flexible approach that aligned with commonly reported practices while addressing gaps in standardization.

The experimental protocols provided comprehensive instructions, including the type, duration, and frequency of exercises, supported by images, video demonstrations, and audio explanations. Each exercise technique was accompanied by a brief rationale written in accessible language for both the parents and clinicians. The exercises were categorized into two types: (1) extra-oral and (2) intra-oral. The pre-operative component consisted of eight stimulation techniques, including cheek, lip, rooting reflex, gum, roof of mouth, sucking reflex, and tongue stimulation. The post-operative component included six techniques, focusing on the cheeks, lips, gums, roof of mouth, and tongue. The protocol recommended performing each exercise technique every four to six hours for 20 to 40 s, with multiple repetitions.

2.3. Procedure

To gather qualitative feedback and insights regarding the protocol in development, 13 individual semi-structured virtual interviews were conducted via videoconference over a two-month period. Prior to data collection, an information sheet was provided to participants and written informed consent was obtained. One week prior to the scheduled interviews, participants were sent an online link to the protocol for review. Interview question guides were developed and tailored to the different contexts of parents and clinicians for use within the interviews and provided one week prior. Interviews with five parent participants lasted between 29 and 77 min, with an average duration of 51 min. Interviews with eight clinician participants lasted between 31 and 65 min, with an average duration of 48 min.

2.4. Analysis

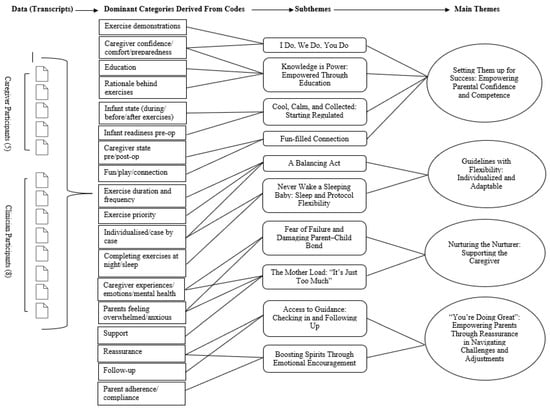

All virtual interviews were videotaped, and audio was recorded and transcribed [25,26]. Transcripts were cross-checked by the research team and sent to participants for review within one week. Thematic analysis (TA) software (NVivo14) was used to identify, generate, and analyze patterns and themes across data collected from the parents and clinicians [28]. Each transcript was independently familiarized and coded by two different researchers to enhance the trustworthiness and reliability of interpretation. Final themes were developed and agreed upon via collaborative discussion within the research team, shown in Figure 1. Researchers engaged in frequent cross-checking and debriefing to reduce researcher bias and enhance overall credibility.

Figure 1.

Example of coding tree for theme development.

3. Results

A range of disciplines were represented within the clinician semi-structured interviews, with the majority being speech pathologists (n = 4), along with several other areas of expertise. The experience of clinicians ranged from 5 to 29 years. Clinicians reported working with clients of varying ages and all had experience providing pre- and/or post-operative care for infants undergoing tongue-tie surgery. Four main themes and ten subthemes were generated from a thematic analysis of the participants’ experiences and opinions of the protocol. These main themes and subthemes are explored in Table 4.

Table 4.

Main themes and subthemes identified with supporting quotes.

3.1. Theme 1: Setting Them Up for Success—Parental Confidence and Competence

Key subthemes identified by participants underscored the importance of fostering parental confidence and competence in successfully implementing the protocol. This was achieved through a combination of practical education from clinicians, hands-on guidance, and fostering a supportive, regulated environment for both the parent and the infant. Parents emphasized direct, face-to-face instruction from clinicians. This approach allowed them to observe, practice, and receive immediate feedback on their technique. As a result, their anxiety decreased, and their confidence in independently performing the stimulation techniques increased. Educating parents about the purpose and significance of the stimulation techniques—along with the potential risks of non-adherence—supported parents in understanding their significance, empowering them to feel more “accountable” and “motivated”. The emotional state of both the parent and infant was also highlighted as a crucial factor in successful protocol implementation. Starting the stimulation techniques when both the parent and infant were “regulated”—a state in which both individuals are emotionally balanced, physiologically calm, and able to engage in interactions without signs of distress—was seen as essential for reducing stress and preventing negative associations with the stimulation. Strategies such as co-regulation—where both the parent and child are in a state of “harmony”—along with creating a positive, playful environment, helped strengthen the parent–child bond and fostered a sense of connection within the dyad. This supportive, nurturing atmosphere not only promoted emotional well-being but also increased parental comfort and confidence, thereby enhancing their competence in following the protocol effectively.

3.2. Theme 2: Guidelines Guide, but Flexibility Heals—Individualized and Adaptable

Another central theme identified by participants was the importance of tailoring post-operative care protocols to the individual needs and circumstances of each family. Many participants emphasized that a rigid, one-size-fits-all approach was often ineffective and instead highlighted the need for flexibility in the protocol and implementation process. Adapting the protocol to accommodate family dynamics, including the parents’ experience, capacity, and daily routines, was seen as crucial for ensuring adherence. Some suggested the inclusion of “priority exercises” for days when full protocol completion is not feasible, with one clinician emphasizing that “it’s better to do something, even if you can’t do everything”. The need for flexibility was also noted with respect to sleep patterns. Both parents and clinicians advocated for prioritizing infant sleep over sleep disruptions due to prescribed post-operative stimulation techniques. A typical reason was due to this feeling “counterintuitive [after] rocking them to sleep for three hours”. Acknowledging the emotional and psychological strain on parents, particularly mothers, was also deemed crucial in protocol flexibility and adaptability. Many parents expressed feelings of guilt or failure when unable to adhere strictly to the protocol, underscoring the need for reassurance and supportive communication from clinicians to mitigate additional stress. Participants agreed that fostering a compassionate, adaptable approach to the protocol would not only ease the emotional burden on parents but also increase the likelihood of successful long-term adherence.

3.3. Theme 3: Nurturing the Nurturer—Supporting the Parent

A prominent theme that emerged was the significant emotional and psychological burden that post-operative care places on parents, particularly mothers. It was highlighted that many parents interpret stimulation technique instructions literally, leading to feelings of “failure” and “guilt” when unable to adhere to the prescribed techniques. Missing a session, even for legitimate reasons, often triggered significant stress, with parents expressing concerns that they had “failed” or “ruined everything” in terms of their infant’s wound healing. This sense of failure was compounded by a fear that the child might develop negative associations with their parent, associating them with pain or discomfort during the stimulation techniques, jeopardizing the parent–child bond. Parents suggested that incorporating words of encouragement and reassurance from other parents into the protocol could alleviate these feelings and support their emotional well-being. Validation of their efforts, even when they were unable to fully comply with the protocol, was seen as crucial for managing emotional strain and preventing feelings of inadequacy. Many parents, particularly first-time mothers or those with limited external support, described the post-operative care regimen as “overwhelming” and emotionally draining. Several parents emphasized that administering post-operative stimulation techniques often effectuates significant emotional distress, particularly surrounding the fear that their child may develop negative emotional responses toward them or associate them with pain. Additionally, several parents likened the experience to a cycle of “trauma”, where the emotional strain of administering the protocol led to stress and anxiety, making it difficult to maintain adherence. They suggested that reassurance could mitigate these feelings through supportive communication both within the protocol and directly from providers. Participants stressed the importance of acknowledging within the protocol the psychological burden parents face and incorporating flexibility or supportive strategies to reduce emotional strain. This recognition would help parents feel understood and supported, ultimately facilitating higher levels of adherence to the prescribed stimulation techniques and improving both the parent’s and child’s well-being.

3.4. Theme 4: “You’re Doing Great”—Empowering Parents Through Reassurance in Navigating Challenges and Adjustments

The critical role of ongoing guidance, emotional support, and reassurance in empowering parents to successfully navigate the challenges of post-operative care also emerged as a core theme. Both parents and clinicians emphasized the importance of regular follow-ups and check-ins, thus providing opportunities for parents to seek clarification, ask questions, and receive feedback on stretching positions, infant comfort, and pain management. This continuous support was seen as essential to validate the efforts, confidence, and capabilities of parents implementing the stimulation techniques. These check-ins also offer a safe space for parents to voice concerns, overcome “whitecoat syndrome”, and receive encouragement from clinicians, all of which contribute to a positive and supportive care experience. In addition to logistical guidance, emotional encouragement was also identified as a key factor in sustaining motivation and adherence. Participants noted that while the care regimen may feel overwhelming initially, reassurance that a routine would eventually develop helped reduce anxiety. Emphasizing the temporary nature of the post-operative care plan, with the message that “it’s not forever” was highlighted as an effective strategy to alleviate stress and maintain motivation. Clinicians also stressed the importance of focusing on effort rather than perfection, which helped reduce apprehension and supported parents in feeling more confident and competent in conducting the stimulation techniques.

4. Discussion

This current study solicited feedback regarding an experimental pre- and post-operative care protocol in development for infants who underwent tongue-tie surgery. The thematic analysis identified four themes that addressed different facets of parental holistic wellness related to the successful implementation of the protocol. There is currently no literature that addresses the priorities and opinions regarding support for adherence and successful implementation of a care protocol from the perspective of parents and clinicians. Holistic factors driving treatment success and adherence were explored, and quality of care was defined from caregivers’ and clinicians’ perspectives. With a scarce evidence base, the existing pre- and post-operative protocols need to consider emerging research, ethical considerations, and stakeholder perspectives. This study addressed the gap by providing qualitative feedback focused on empowering and motivating caregivers. It emphasized that a holistic, family-centered approach is crucial for success and adherence to pre- and post-operative management, beyond oral stimulation types, frequency, and dosage.

Empowering and motivating parents within an infant treatment protocol requires fortitude within a clinician–parent relationship. Our findings advocate for ongoing clinician guidance, access, emotional encouragement, and recognition of an individualized approach as key facilitators in parent adherence. These findings corroborate similar studies within the infant neonatal literature, which conclude that clinician empathy and a sense of “family” with the staff contribute to improved therapeutic success and caregiver well-being outcomes [29,30,31,32]. Additionally, the emotional capacity of the clinician should be respected. Clinician burnout and compassion fatigue are excessively evident within modern medical literature but lacking application to the TT context [33,34].

Participants defined “setting up for success” by placing value on in-person, face-to-face education and in-depth demonstrations from their providers. These recommendations align with the perspectives of parents and nurses in the neonatal and surgical literature, which suggest that upskilled parents reduce dependency on clinicians. Proficiency instills parental autonomy and self-confidence when providing home care for their infants. This is suggested to facilitate positive overall health outcomes and recovery for the infant [35,36]. Our findings suggest that fostering an experience centered on parental autonomy empowers parents to confidently care for their child, rather than feeling inadequate or hesitant [29].

The findings also suggested that it was counterproductive to focus solely on reducing infant tension without first addressing parental anxiety. Acknowledged within the TT literature, heightened caregiver stress and anxiety are rooted in a lack of education and uncertainty towards the surgical procedure [37,38]. Subsequently, this study found that these emotions stemmed from fear and guilt when implementing post-operative care for their child. Similarly, studies in the infant mental health literature indicate that the fear of jeopardizing the parent–infant bond dictates caregiver adherence to treatment protocols [39,40]. Participants emphasized embedding a routine of play, fun, and skin-on-skin contact into the post-operative practices, further supporting the neonatal evidence base [41,42]. This study and the current literature emphasize parental empowerment, aiming to restore control and harmony within the parent–infant dyad to prevent negative associations with pre- and post-operative care. Additionally to clinician support, parents expressed a desire for peer encouragement, particularly mother-to-mother and parent-to-parent support, emphasizing the value of shared experiences. The emerging literature supports the concept of peer mentoring and lived experience roles within parent mental health practices [43]. Implementing this approach in the context of TT care protocols suggests that validation from those who have faced similar challenges can mitigate feelings of isolation and anxiety. Considering this, the recent literature is placing higher regard for a family-centered care model within an infant health population, calling for “individualization” over “standardization” [29]. Participants disclaimed that with the challenges inflicted by parenthood, it is unlikely and unrealistic that a protocol would be adhered to flawlessly. This is similarly implied within the nursing literature, which states that standardized protocols cannot successfully address all aspects of patient-centered care [44]. The argument for flexibility stems from parents calling for a “low demand” care regime that prioritizes infant sleep routines. Infant sleep literature shows that sleep disturbances lead to increased symptoms of anxiety, depression, and fatigue among new parents, thereby impacting their capacity to adhere to a care protocol [42]. These findings suggest that while standardization is ideal, it should serve as a foundation with flexibility, allowing for clinical judgment and specific patient needs, balancing “parental preferences” with “protocol requirements”. This is asserted to be integral in supporting a family-centered approach to TT management.

This current study highlighted that focusing solely on stimulation techniques is simplistic; clinicians must also consider the capacity of parents, providing education and upskilling, and providing ongoing support and reassurance. There is an emphasis on the necessity for standardized pre- and post-operative care protocols by clinicians and the TT literature. However, the findings from this current study underscore the importance of adopting a family-centered, needs-oriented approach to TT pre- and post-operative care. Therefore, these two frameworks are not mutually exclusive but can and should be integrated to complement one another effectively. The voices of both parents and clinicians are important in TT management, and this study allowed clinicians with various years of experience to share their experiences and insights.

This study was limited to the inclusion of a relatively small sample size of 13 parents and clinicians, representing the views of clinicians from Australia, Canada, and the United States of America. Parent participants were all Australian mothers, and hence did not represent lived experiences from the perspectives of fathers nor parents in other countries. Additionally, the time taken by parents and clinicians to comprehensively review each modality of the protocol varied among participants. The protocol was typically sent to participants one week prior to the scheduled interview. However, for some, this was not possible due to rescheduling the interview at an earlier than expected date. Some participants had also not independently reviewed the protocol prior to their interview and hence were required to review in real time. This could have impacted on the amount and specificity of feedback provided, leading to potential variability in the depth of understanding of the experimental pre- and post-operative care protocols. During interviews, occasional leading and closed-ended questions were evident, which may have led participants in a pre-conceived direction unknowingly, reducing the reliability of data collection.

Future research should focus on developing tools to identify and characterize parent needs and wants necessary to facilitate the successful implementation of the protocol efficiently and optimally set up a triad framework whereby the clinician, the infant, and the parent can support each other on all levels to optimize and realize wellness outcomes for all parties.

Clinical Implications

The clinical implications of this study highlight the need for a holistic, family-centered approach to pre- and post-operative care for infants undergoing TT surgery. The findings emphasize the importance of empowering parents through tailored support that addresses both their emotional well-being and practical needs. Providing in-depth education, ongoing clinician guidance, and a focus on stress management and emotional well-being are critical factors in fostering parental confidence and adherence to care protocols. Furthermore, flexibility within standardized care protocols is essential to accommodate the diverse needs of families, allowing for adjustments based on individual circumstances such as infant sleep routines and parent capacity. This will further optimize outcomes for the infant, parent, and family. This study also emphasizes the value of peer support, particularly mother-to-mother or parent-to-parent networks, to reduce feelings of isolation and anxiety. Clinicians must recognize the emotional aspects of care, ensuring that parents feel supported and confident in their role in the care process. This research recommends that clinicians prioritize parent needs and create a triad framework that optimally supports the infant, parent, and clinician throughout the treatment process.

5. Conclusions

This study sought to contribute to the profession’s knowledge base by gathering feedback on an evidence-based protocol from a community advisory group of parents and currently practicing clinicians. This research highlighted the importance of empowering and building parent capacity through education, ongoing clinician support, and peer encouragement to increase confidence and autonomy. The findings outline that a family-centered approach is vital for successful implementation, advocating for individualization over strict standardization. This aligns with the contemporary literature that emphasizes the value of adapting care to meet the unique needs of families—specifically the child and the parent. This study acknowledges the need for broader international representation and suggests that including samples from different countries could help to capture diverse perspectives. Nevertheless, our study contributes valuable insights into the parent experience and highlights areas for future research. This study recommends a pilot evaluation of the proposed care protocol, using standardized outcome measures to assess its effectiveness. The next step in this research is the validation and piloting of the proposed evidence-based care protocol. Overall, this study advocates for a paradigm shift in clinical practices regarding TT management, emphasizing the prioritization of holistic and family-centered care to enhance parental confidence and capacity in supporting treatment adherence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization T.C., E.N., R.J.T. and S.S; methodology, T.C, E.N., R.J.T. and S.S.; software, T.C., E.N., R.J.T. and S.S.; formal analysis, T.C., E.N., R.J.T. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C., E.N., R.J.T. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, T.C, E.N., R.J.T. and S.S.; supervision, R.J.T. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC2024-0106, Approval Date: 12 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and analyzed during this current study are not publicly available due to ethics only being provided for this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the infant participants, caregivers, and health professionals who participated in this project. We would also like to extend special thanks to Ella Beadle and Megan van der Linde for their valued contributions to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hatami, A.; Dreyer, C.W.; Meade, M.J.; Kaur, S. Effectiveness of tongue-tie assessment tools in diagnosing and fulfilling lingual frenectomy criteria: A systematic review. Aust. Dent. J. 2022, 67, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, C.; Chetwynd, E.; Costello, R. Ankyloglossia identification, diagnosis, and frenotomy: A qualitative study of community referral pathways. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, M.E.; Gilliland, A.M.; LeFort, Y. Complications and misdiagnoses associated with infant frenotomy: Results of a healthcare professional survey. Int. Breastfeed J. 2022, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Dental Association. Ankyloglossia and Oral Frena Consensus Statement. 2020. Available online: https://ada.org.au/unauthorized-access (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Walsh, J.; Tunkel, D. Diagnosis and treatment of ankyloglossia in newborns and infants: A review. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 143, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, D.; Bogaardt, H.; Lau, T.; Docking, K. Ankyloglossia in Australia: Practices of health professionals. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 171, 111649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekher, R.; Lin, L.; Zhang, R.; Hoppe, I.C.; Taylor, J.A.; Bartlett, S.P.; Swanson, J.W. How to treat a tongue-tie: An evidence-based algorithm of care. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, A.H.; Lalakea, M.L. Ankyloglossia: Controversies in management. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2000, 54, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrés-Amat, E.; Pastor-Vera, T.; Rodriguez-Alessi, P.; Mareque-Bueno, J.; Ferrés-Padró, E. The prevalence of ankyloglossia in 302 newborns with breastfeeding problems and sucking difficulties in Barcelona: A descriptive study. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrés-Amat, E.; Pastor-Vera, T.; Ferrés-Amat, E.; Mareque-Bueno, J.; Prats-Armengol, J.; Ferrés-Padró, E. Multidisciplinary management of ankyloglossia in childhood. Treatment of 101 cases. A protocol. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2016, 21, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrés-Amat, E.; Pastor-Vera, T.; Rodríguez-Alessi, P.; Ferrés-Amat, E.; Mareque-Bueno, J.; Ferrés-Padró, E. Management of ankyloglossia and breastfeeding difficulties in the newborn: Breastfeeding sessions, myofunctional therapy, and frenotomy. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2016, 2016, 3010594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, R.; Hughes, L. Speech and feeding improvements in children after posterior tongue-tie release: A case series. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. 2018, 7, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandarkar, K.P.; Dar, T.; Karia, L.; Upadhyaya, M. Post Frenotomy Massage for Ankyloglossia in Infants—Does It Improve Breastfeeding and Reduce Recurrence? Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrocho-Rangel, A.; Herrera-Badillo, D.; Pérez-Alfaro, I.; Fierro-Serna, V.; Pozos-Guillén, A. Treatment of ankyloglossia with dental laser in paediatric patients: Scoping review and a case report. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaheri, B.A.; Cole, M.; Fausel, S.C.; Chuop, M.; Mace, J.C. Breastfeeding improvement following tongue-tie and lip-tie release: A prospective cohort study. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaikaria, A.; Pahuja, S.K.; Thakur, S.; Negi, P. Treatment of partial ankyloglossia using Hazelbaker Assessment Tool for Lingual Frenulum Function (HATLFF): A case report with 6-month follow-up. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 12, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaikumar, S.; Srinivasan, L.; Babu, S.K.; Gandhimadhi, D.; Margabandhu, M. Laser-assisted frenectomy followed by post-operative tongue exercises in ankyloglossia: A report of two cases. Cureus 2022, 14, e31435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, N.A.; Rashidi, N.A.M.; Teni, N.F.M.; Ardini, Y.D.; Jamani, N.A. Mothers’ Perceptions and Experiences on Tongue-tie and Frenotomy: A Qualitative Study. Malay. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 18, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dunwoodie, K.; Macaulay, L.; Newman, A. Qualitative interviewing in the field of work and organisational psychology: Benefits, challenges and guidelines for researchers and reviewers. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 863–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, B. Participatory action research as a research approach: Advantages, limitations and criticisms. Qual. Res. J. 2023, 23, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, F.; Breton, N.; Moreno-Tabarez, U.; Delgado, J.; Rua, M.; de-Graft Aikins, A.; Hodgetts, D. Participatory action research. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Teams [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.office.com/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Ahmed, S.K. The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, S.; Grant, H.; Tseng, R.J. Beyond surgery: Pre-and post-operative care in children with ankyloglossia. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 35, 233–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Streams [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.office.com/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Word [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.office.com/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Nvivo14 [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://lumivero.com/product/nvivo/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Schuetz Haemmerli, N.; Stoffel, L.; Schmitt, K.U.; Khan, J.; Humpl, T.; Nelle, M.; Cignacco, E. Enhancing parents’ well-being after preterm birth—A qualitative evaluation of the “transition to home” model of care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, G.; Sawyer, A.; Rabe, H.; Abbott, J.; Gyte, G.; Duley, L.; Ayers, S. Parents’ views on care of their very premature babies in neonatal intensive care units: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Medina, I.M.; Granero-Molina, J.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Jimenez-Lasserrotte, M.d.M.; Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Fernández-Sola, C. Socio-family support for parents of technology-dependent extremely preterm infants after hospital discharge. J. Child Health Care 2022, 26, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bry, A.; Wigert, H. Psychosocial support for parents of extremely preterm infants in neonatal intensive care: A qualitative interview study. BMC Psychol. 2019, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, J.; Bhutani, S.; Balhara, Y.P.S.; Kalra, S. Compassion fatigue and burnout amongst clinicians: A medical exploratory study. Indian. J. Psychol. Med. 2012, 34, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, A.; Geithner, E.; Stroustrup, A.; Waldman, E. Compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction in neonatologists in the US. J. Perinatol. 2016, 36, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.; Shorey, S. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on the psychological outcomes of parents with preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2024, 74, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staveski, S.L.; Parveen, V.; Madathil, S.B.; Kools, S.; Franck, L.S. Parent education discharge instruction program for care of children at home after cardiac surgery in Southern India. Cardiol. Young 2016, 26, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P. Pre and Post Procedure Parent Education to Reduce Anxiety Related to Tongue-Tie. Ph.D. Thesis, Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S.; Hairston, T.K.; Giorgi, M.; Links, A.R.; Boss, E.F.; Walsh, J. Speaking in tongues: What parents really think about tongue-tie surgery for their infants. Clin. Pediatr. 2020, 59, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David Vainberg, L.; Vardi, A.; Jacoby, R. The experiences of parents of children undergoing surgery for congenital heart defects: A holistic model of care. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-L.; Ma, J.-J.; Meng, H.-H.; Zhou, J. Mothers’ experiences of neonatal intensive care: A systematic review and implications for clinical practice. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network. Developmentally Supportive Care for Newborn Infants: Practical Guideline; Contract No.: 2006-0027; NSW Government: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2022.

- Warre, R.; O’Brien, K.; Lee, S.K. Parents as the primary caregivers for their infant in the NICU: Benefits and challenges. Neoreviews 2014, 15, e472–e477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castles, C.; Stewart, V.; Slattery, M.; Bradshaw, N.; Roennfeldt, H. Supervision of the mental health lived experience workforce in Australia: A scoping review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 1654–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycroft-Malone, J.; Fontenla, M.; Seers, K.; Bick, D. Protocol-based care: The standardisation of decision-making? J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 1490–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).