Clinical Perspectives on Post-Operative Care for Tethered Oral Tissues (TOTs)

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Active Wound Management

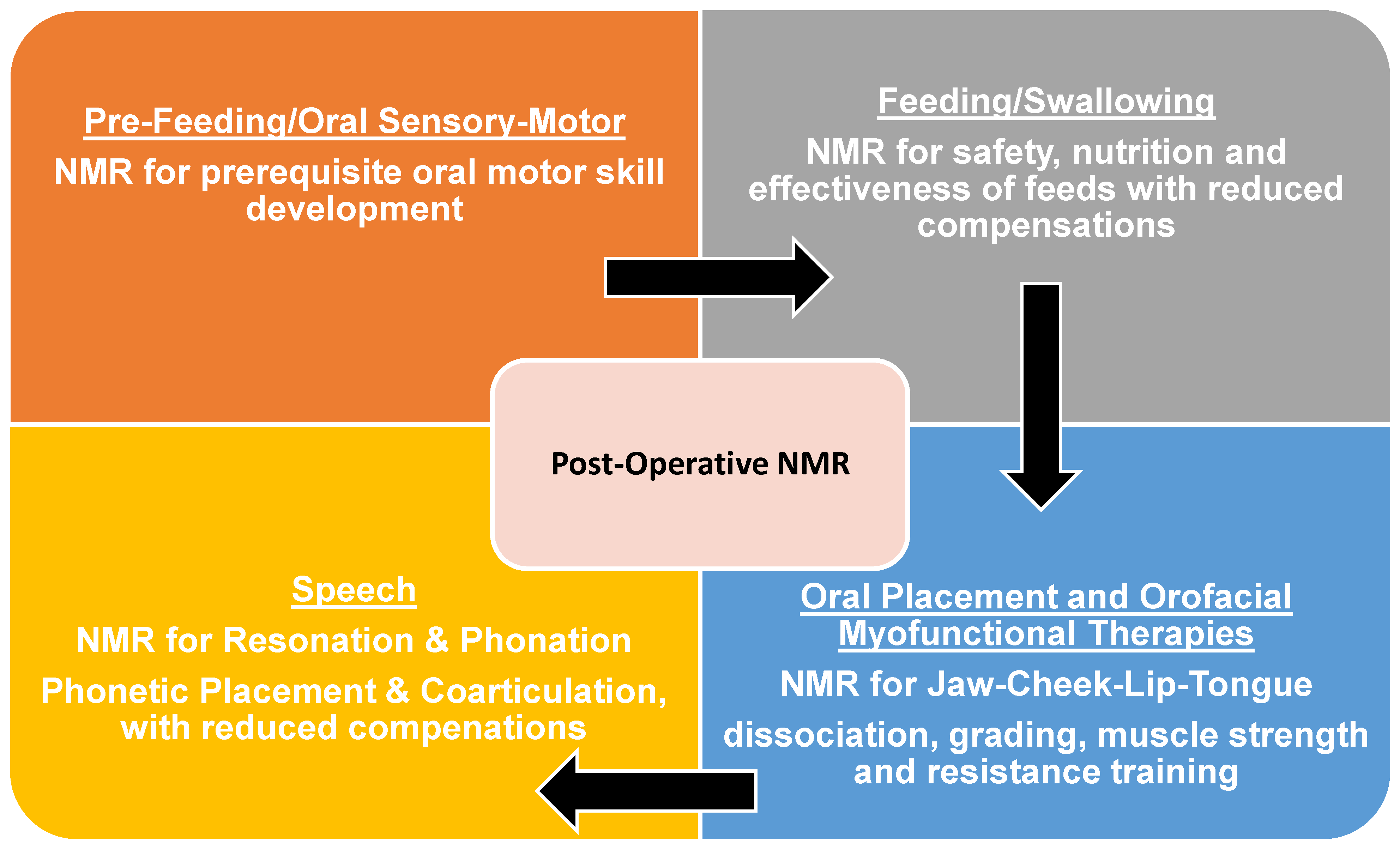

Neuromuscular Re-education

Scope of Practice

NEW PERSPECTIVE

Pre-feeding and Oral Sensory-Motor Function

Feeding/Swallowing

Speech

NMR Considerations

CONCLUSION

Acknowledgments

Declarations of Interest

Author Contributions

Funding

Appendix A

References

- Ajimsha, M. S., N. R. Al-Mudahka, and J. A. Al-Madzhar. 2015. Effectiveness of myofascial release: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 19, 1: 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. 2022. Policy on management of the frenulum in pediatric patients. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry, 80–85. Available online: https://www.aapd.org/research/oral-health-policies--recommendations/managment-of-the-frenulum-in-pediatric-dental-patients/.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. 2022. ADHA Policy Manual. Available online: https://www.adha.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ADHA_Policy-_Manual_FY22.pdf.

- American Occupational Therapy Association. 2021. Occupational therapy scope of practice. Am J Occup Ther 75 Supplement 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Physical Therapy Association. 2017. Scope of practice. Available online: https://www.apta.org/contentassets/a400d547ca63438db1349c4a69bf7ead/position-pt-scope-practice.pdf.

- American Physical Therapy Association. 2020. APTA Analysis: The Value of Physical Therapy in Wound Care. Available online: https://www.apta.org/article/2020/10/30/analysis-value-physical-therapy-wound-care.

- American Physical Therapy Association. 2022. APTA specialist certification: become a board-certified wound management specialist. Available online: https://specialization.apta.org/become-a-specialist/wound-management.

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. 2016. Scope of practice in speech-language pathology. Available online: https://www.asha.org/policy/.

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. n.d.AOrofacial myofunctional disorders. (Practice Portal). Available online: www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Orofacial-Myofunctional-Disorders/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. n.d.BPediatric feeding and swallowing. (Practice Portal). Available online: www.asha.org/practice-portal/clinical-topics/pediatric-dysphagia/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Amini, D. 2018. Role of occupational therapy in wound management. AJOT: American Journal of Occupational Therapy 72. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A574057088/AONE?u=anon~cf4766ca&sid=googleScholar&xid=f1cf5073.

- Bahr, D. 2010. Nobody ever told me (or my mother) that! Everything from bottles and breathing to healthy speech development! Sensory World. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, D., and S. Rosenfeld-Johnson. 2010. Treatment of children with speech oral placement disorders (OPDs): a paradigm emerges. Communications Quarterly 31, 3: 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, R. 2018. Tongue-tied: how a tiny string under the tongue impacts nursing, speech, feeding, and more. Alabama Tongue-Tie Center. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, R., and L. Hughes. 2018. Speech and feeding improvements in children after posterior tongue-tie release: a case series. International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics 7, 3: 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, R., R. Merkel-Walsh, B. S. Baxter, A. Lashley, and N. R. Rendell. 2020. Functional improvements of speech, feeding, and sleep after lingual frenectomy tongue-tie release: a prospective cohort study. Clinical Pediatrics 59, 9-10: 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg-Drazin, P. 2016. IBCLCs and craniosacral therapists: strange bedfellows or perfect match? The Journal of Clinical Lactation 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandarkar, K. P., T. Dar, L. Karia, and M. Upadhyaya. 2022. Post frenotomy massage for ankyloglossia in infants-does it improve breastfeeding and reduce recurrence? Maternal and child health journal 26, 8: 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, M., K. Gatto, L. D’Onofrio, R. Merkel-Walsh, and N. Archambault. 2018. Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders. International Association of Orofacial Myology. Available online: http://iaom.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/OMD-Overview-IAOM.pdf.

- Browne, D. 1959. Tongue-Tie. British Medical Journal 2: 1181–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, E. 2017. IBCLC scope for tongue tie assessment. Clinical Lactation 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, L., A. Landry, A. Deshpande, C. Marchica, A. Cooley, and N. Raol. 2020. Posterior tongue tie, base of tongue movement, and pharyngeal dysphagia: what is the connection? Dysphagia 35, 1: 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brożek-Mądry, E., Z. Burska, Z. Steć, M. Burghard, and A. Krzeski. 2021. Short lingual frenulum and head-forward posture in children with the risk of obstructive sleep apnea. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 144: 110699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, L. S., H. Frey, M. Davis, M. Robbins, C. Spankovich, V. Narisetty, and J. D. Carron. 2020. Characteristics and considerations for children with ankyloglossia undergoing frenulectomy for dysphagia and aspiration. American Journal of Otolaryngology 41, 3: 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscemi, A., M. Coco, A. Rapisarda, G. Frazzetto, D. Di Rosa, S. Feo, M. Piluso, L. P. Presente, S. S. Campisi, and P. Desirò. 2021. Tongue stretching technique and clinical proposal. Journal of Complementary & Integrative Medicine 19, 2: 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, M. T., C. C. Corrêa, A. J. Cassettari, L. T. Giacomin, A. C. Faria, A. P. S. M. Moreira, I. Magalhães, M. O. D. Cunha, S. A. T. Weber, E. Zancanella, and A. J. Machado Júnior. 2022. Is ankyloglossia associated with obstructive sleep apnea? Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology 88, Supl. 1: S156–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloway, C., C. J. Hersh, R. Baars, S. Sally, G. Diercks, and C. J. Hartnick. 2019. Association of feeding evaluation with frenotomy rates in infants with breastfeeding difficulties. JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery 145, 9: 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanha, S. M. A., R. L. C. Martinelli, and D. B. Palhares. 2019. Association between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. CoDAS 31, 1: e20170264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2016. Frenectomy for the correction of ankyloglossia: a review of clinical effectiveness and guidelines. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK168998.

- Carrasco-Llatas, M., C. O’Connor-Reina, and C. Calvo-Henríquez. 2021. The role of myofunctional therapy in treating sleep-disordered breathing: a state-of-the-art review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 14: 7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnadurai, S., D. O. Francis, R. A. Epstein, A. Morad, S. Kohanim, and M. McPheeters. 2015. Treatment of ankyloglossia for reasons other than breastfeeding: a systematic review. Pediatrics 135, 6: e1467–e1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordray, H., G. N. Mahendran, C. S. Tey, J. Nemeth, and N. Raol. 2023. The impact of ankyloglossia beyond breastfeeding: a scoping review of potential symptoms. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 32, 6: 3048–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coryllos, E., C. Watson Genna, and A. Salloum. 2004. Congenital tongue-tie and its impact on breastfeeding. American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Breastfeeding. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Romero, M., B. Espínola-Docio, J. M. Paricio-Talayero, and N. M. Díaz-Gómez. 2021. Ankyloglossia in breastfeeding infants: an update. Anquiloglosia en el lactante amamantado. Puesta al día. Archivos Argentinos de Pediatria 119, 6: e600–e609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daggumati, S., J. E. Cohn, M. J. Brennan, M. Evarts, B. J. McKinnon, and A. R. Terk. 2019. Speech and language outcomes in patients with ankyloglossia undergoing frenulectomy: a retrospective pilot study. OTO open 3, 1: 2473974X19826943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devishree, S. K. Gujjari, and P. V. Shubhashini. 2012. Frenectomy: a review with the reports of surgical techniques. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR 6, 9: 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dydyk, A., M. Milona, J. Janiszewska-Olszowska, M. Wyganowska, and K. Grocholewicz. 2023. Influence of shortened tongue frenulum on tongue mobility, speech, and occlusion. Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, 23: 7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fioravanti, M., F. Zara, I. Vozza, A. Polimeni, and G. L. Sfasciotti. 2021. The efficacy of lingual laser frenectomy in pediatric OSAS: a randomized double-blinded and controlled clinical study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 11: 6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlenza, G. P., N. M. Paradise Black, E. G. McNamara, and S. E. Sullivan. 2010. Ankyloglossia, exclusive breastfeeding, and failure to thrive. Pediatrics 125, 6: e1500–e1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiano, N., B. Bergstrom, A. Dralle, and R. Throneburg. 2019. Tongue-tie and speech articulation. [Poster presentation]. 60th Annual Illinois Speech-Language Hearing Association Convention, Rosemont, IL, USA; 2019, Poster presentation: Rosemont, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Genna, C. W., Y. Saperstein, S. A. Siegel, A. F. Laine, and D. Elad. 2021. Quantitative imaging of tongue kinematics during infant feeding and adult swallowing reveals highly conserved patterns. Physiological Reports 9, 3: e14685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaheri, B. A. n.d.Aftercare. Available online: https://www.drghaheri.com/aftercare.

- Ghaheri, B. A., M. Cole, S. C. Fausel, M. Chuop, and J. C. Mace. 2017. Breastfeeding improvement following tongue-tie and lip-tie release: a prospective cohort study. The Laryngoscope 127, 5: 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaheri, B. A., D. Lincoln, T. N. T. Mai, and J. C. Mace. 2022. Objective improvement after frenotomy for posterior tongue-tie: A prospective randomized trial. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery: Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 166, 5: 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayoumi-Anaraki, Z., F. Majami, F. Farahnakimoghadam, S. Barbari, N. Tahmasebifard, and J. Sarabadani. 2022. Prevalence of tongue-tie and evaluation of speech sound disorders in young children. Clinical Archives of Communication Disorders 7: 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Garrido, M. D. P., C. Garcia-Munoz, M. Rodríguez-Huguet, F. J. Martin-Vega, G. Gonzalez-Medina, and M. J. Vinolo-Gil. 2022. Effectiveness of myofunctional therapy in ankyloglossia: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 19: 12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, O. L. 1954. Principles of neuromuscular reeducation. JAMA 156, 15: 1396–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Orofacial Myology. 2023. Faq. Available online: https://www.iaom.com/faq/.

- International Board-Certified Lactation Consultant®. 2018. Scope of practice. Available online: https://iblce.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/scope-of-practice-2018.pdf.

- Ito, Y., T. Shimizu, T. Nakamura, and C. Takatama. 2015. Effectiveness of tongue-tie division for speech disorder in children. Pediatrics International: Official Journal of the Japan Pediatric Society 57, 2: 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlow, L. 2001. Infant reflux and aerophagia associated with maxillary lip-tie and ankyloglossia. Clinical Lactation 2–4: 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlow, L. 2015. TOTS-tethered oral tissues: the assessment and diagnosis of the tongue and upper lip ties in breastfeeding. Oral Health. Available online: http://www.oralhealthgroup.com/features/tots-tethered-oral-tissues-the-assessment-and-diagnosis-of-the-tongue-and-upper-lip-ties-in/.

- Kumin, L., K.C. Von Hagel, and D.C. Bahr. 2001. An effective oral motor intervention protocol for infants and toddlers with low muscle tone. Infant-Toddler Intervention 11: 181–200. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2002-12817-002.

- Larjava, H. 2012. Oral wound healing: cell biology. Wiley-Blackhead. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, B., P. Nahirniak, and C.A. Morrison. 2022. Wound debridement. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing: Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507882.

- Marchesan, I. Q. 2004. Lingual frenulum: classification and speech interference. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 30, 1: 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, R.L., I.Q. Marchesan, R.J. Gusmão, A.D. Rodrigues, and G. Berretin-Félix. 2014. Histological characteristics of altered human lingual frenulum. International Journal of Pediatrics andChild Health Care 2: 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaughan, D., L. Sheard, N. Cullum, J. Dumville, and I. Chetter. 2018. Patients' perceptions and experiences of living with a surgical wound healing by secondary intention: a qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 77: 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaux, A., M. Savage, and C. Gonsoulin. 2016. Tongue ties and speech sound disorders: what are we overlooking? [Poster Session]. Annual Convention of The American Speech and Hearing Association, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel-Walsh, R. 2014. Teaming up to correct tongue tie. ASHA Wire: Leader Live. Available online: https://leader.pubs.asha.org/doi/10.1044/leader.FTR5.19012014.np.

- Merkel-Walsh, R. 2020. Orofacial myofunctional therapy with children ages 0–4 and individuals with special needs. International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy 46, 1: 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel-Walsh, R., and K. Gatto. 2021. The team approach in treating oral sensory-motor dysfunction in newborns, infants, and babies with a diagnosis of tethered oral tissue. Journal of The American Laser Study Club 4, 1: 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel-Walsh, R., and L. Overland. 2018. Functional assessment and remediation of tethered oral tissues(s). TalkTools®. [Google Scholar]

- Messner, A. H., and M. L. Lalakea. 2002. The effect of ankyloglossia on speech in children. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery: Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 127, 6: 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, T. 2001. Anatomy trains: myofascial meridians for manual and movement therapists. Churchill Livingstone. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, C. S. 2011. International association of orofacial myology history: origin-background-contributors. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 37(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, N., N. Keough, D. T. Geddes, S. M. Pransky, and S. A. Mirjalili. 2019a. Defining the anatomy of the neonatal lingual frenulum. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.) 32, 6: 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, N., S. M. Pransky, D. T. Geddes, and S. A. Mirjalili. 2019b. What is a tongue tie? Defining the anatomy of the in-situ lingual frenulum. Clinical Anatomy (New York, N.Y.) 32, 6: 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S., and M. Klein. 2000. Pre-feeding skills, 2nd ed. Therapy Skill Builders. [Google Scholar]

- New York Department of Education, Office of the Professions. 2023. Part 61, Dentistry, dental hygiene, and registered dental assisting. Available online: https://www.op.nysed.gov/title8/regulations-commissioner-education/part-61.

- North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners. 2024. Chapter 90, Article 16. Dental Hygeine Act. Available online: https://www.ncleg.gov/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/HTML/ByArticle/Chapter_90/Article_16.html.

- Oh, J. S., S. Zaghi, C. Peterson, C. S. Law, D. Silva, and A. J. Yoon. 2021. Determinants of sleep-disordered breathing during the mixed dentition: development of a functional airway evaluation screening tool (FAIREST-6). Pediatric dentistry 43, 4: 262–272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oldfield, M.C. 1959. Tongue-tie. British Medical Journal 2: 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overland, L., and R. Merkel-Walsh. 2013. A sensory-motor approach to feeding. TalkTools. [Google Scholar]

- Pavan, P. G., A. Stecco, R. Stern, and C. Stecco. 2014. Painful connections: densification versus fibrosis of fascia. Current pain and headache reports 18, 8: 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potock, M. 2017. Three structures in a child’s mouth that can cause picky eating. ASHA Wire: Leader Live. Available online: https://leader.pubs.asha.org/do/10.1044/three-structures-in-a-childs-mouth-that-can-cause-picky-eating/full/.

- Pransky, S. M., D. Lago, and P. Hong. 2015. Breastfeeding difficulties and oral cavity anomalies: The influence of posterior ankyloglossia and upper-lip ties. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 79, 10: 1714–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protásio, A. C. R., E. L. Galvão, and S. G. M. Falci. 2019. Laser techniques or scalpel incision for labial frenectomy: a meta-analysis. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery 18, 4: 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M. 2021. Tummy time: a crucial neurodevelopment process. Journal of the American Laser Study Club 41, 1: 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld-Johnson, S. 2001. Effective exercises for a short frenum. Advance Magazine for Speech- Language Pathologists. [Google Scholar]

- Salt, H., M. Claessen, T. Johnston, and S. Smart. 2020. Speech production in young children with tongue-tie. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 134: 110035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summersgill, I., G. Nguyen, C. Grey, L. Norouz-Knutsen, R. Merkel-Walsh, C. Katzenmeir, B. Rafii, and S. Zaghi. 2023. Muscle tension dysphonia in singers and professional speakers with ankyloglossia: impact of treatment with lingual frenuloplasty and orofacial myofunctional therapy. International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy 49(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, D., G. Cacciagrano, S. D Ercole, F. Piccari, A. Maiolo, and M. Tieri. 2021. Short lingual frenulum: from diagnosis to laser and speech-language therapy. European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 22, 1: 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollheim, D., and Z. Meeker. 2023. 3 types of wound closure and what they mean. Wound Care Education Institute. Available online: https://blog.wcei.net/3-types-of-wound-closure.

- Zaghi, S., S. Valcu-Pinkerton, M. Jabara, L. Norouz-Knutsen, C. Govardhan, J. Moeller, V. Sinkus, R. S. Thorsen, V. Downing, M. Camacho, A. Yoon, W. M. Hang, B. Hockel, C. Guilleminault, and S. Y. Liu. 2019. Lingual frenuloplasty with myofunctional therapy: exploring safety and efficacy in 348 cases. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 4, 5: 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghi, S., S. Shamtoob, C. Peterson, L. Christianson, S. Valcu-Pinkerton, Z. Peeran, B. Fung, D. Kwok-Keung Ng, T. Jagomagi, N. Archambault, B. O'Connor, K. Winslow, M. Lano, J. Murdock, L. Morrissey, and A. Yoon. 2021. Assessment of posterior tongue mobility using lingual-palatal suction: progress towards a functional definition of ankyloglossia. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 48, 6: 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2024 by the authors. 2022 Robyn Merkel-Walsh, Lori L. Overland.

Share and Cite

Merkel-Walsh, R.; Overland, L.L. Clinical Perspectives on Post-Operative Care for Tethered Oral Tissues (TOTs). Int. J. Orofac. Myol. Myofunct. Ther. 2024, 50, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2024.50.2.2

Merkel-Walsh R, Overland LL. Clinical Perspectives on Post-Operative Care for Tethered Oral Tissues (TOTs). International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy. 2024; 50(2):1-13. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2024.50.2.2

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerkel-Walsh, Robyn, and Lori L. Overland. 2024. "Clinical Perspectives on Post-Operative Care for Tethered Oral Tissues (TOTs)" International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy 50, no. 2: 1-13. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2024.50.2.2

APA StyleMerkel-Walsh, R., & Overland, L. L. (2024). Clinical Perspectives on Post-Operative Care for Tethered Oral Tissues (TOTs). International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy, 50(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2024.50.2.2