Self-Care Treatment on Patients with Wakefulness Bruxism

Abstract

:INTRODUCTION

METHODS

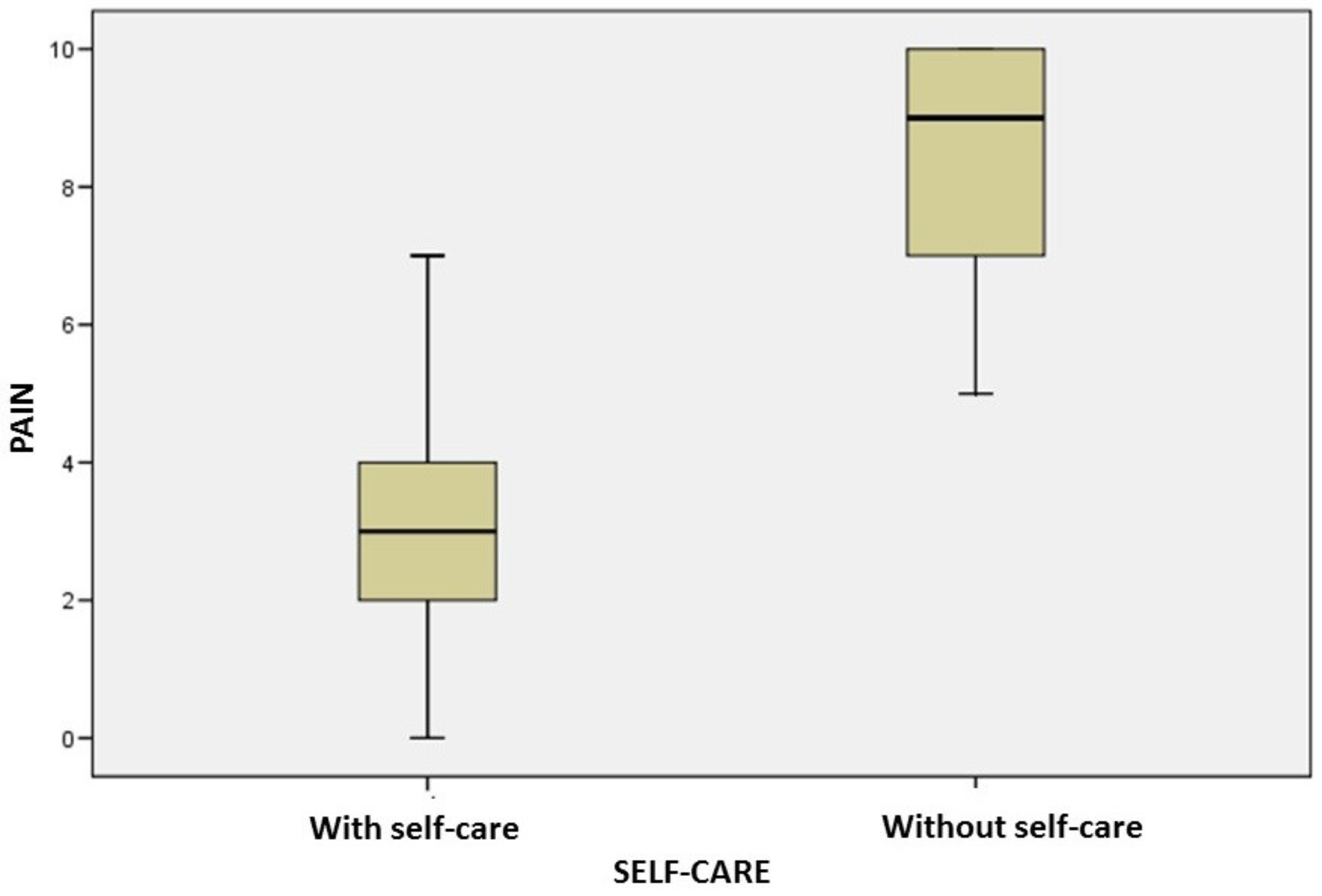

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSION

APPENDIX A: SELF-CARE GUIDE

| SLEEP HYGIENE GUIDELINES (ORLANDI et al., 2012) |

| Try to sleep every day at the same time. Thus, your body will always prepare to sleep at the same time. You will fall asleep more quickly in the coming weeks! |

| Do not use the room where you sleep to work, study or eat. It should just be the place to sleep. |

| Avoid watching TV before bed. Watching TV can leave you agitated and can lessen your sleep! |

| Rest your mind and relax your body for at least an hour before bedtime. Do not solve big problems at this time of the day. |

| Do not drink coffee, tea and chocolate after 5 pm. |

| Do not drink alcohol before going to bed. Although they help to relax, they disturb the quality of your sleep; if possible, have a glass of milk. |

| If you are a smoker, do not smoke for two to three hours before bed. |

| Try to make lighter meals over dinner. Good choices are salad and vegetables. Many greasy foods like fried foods, for example, make your stomach heavier and hamper your sleep! |

| Keep your room at a pleasant temperature. Excessive heat and cold change the quality of your sleep. Also, wrap yourself well, to avoid possible muscular “contractures”. |

| Noises and clarity can lead to poor sleep. Therefore, seek to sleep where there is silence and low light. |

| Physical exercises improve the quality of your sleep. But beware: try to work out in the morning or in the afternoon. If done close to bedtime, they will decrease the quality of your sleep. It is also important that you practice exercises that you enjoy, that leave you happy and excited. In addition to improving the quality of your sleep, you stay in shape. |

| Try to elaborate a routine before going to bed. For example: putting the cat out, locking the doors, brushing teeth .... This makes your body used and reminds you that it is time to go to sleep, reducing the time you wait for sleep to arrive. |

| Warm baths before bedtime are recommended to combat your insomnia. They relax your body and your mind. |

| Do not doze more than twice during the same week. This decreases the need for nighttime sleep. |

| Always sleep in a bed where you feel comfortable. This is very important so that you can completely relax to fall asleep. |

| Avoid “fighting” with the bed. Sleep only long enough to feel good. Do not stay in bed longer than the time required. |

| When you feel sleepless, get up and do something tiring or repetitive, such as reading a book from an uninteresting subject. |

| Say no to medicines! You should take sleeping pills only if they are taken with medical advice. |

REFERENCES

- Alencar, F. P. G., Jr. 2005. Oclusão, Dores Orofaciais e Cefaleias, 1st ed. São Paulo: Santos. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaya, T. A., H. R. Zukowska, L. Uemoto, S. S. I. Oliveira, O. E. R. Martinez, M. A. C. Garcia, and et al. 2013. Alterações psicossomáticas e hábitos parafuncionais em indivíduos com disfunção temporomandibular. Saúde e Pesquisa 6, 2: 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini, E. M. G. 2004. Articulação temporomandibular e fonoaudiologia. Tratado de fonoaudiologia, São Paulo: Roca. [Google Scholar]

- Campi, L. B., C. M. Camparis, P. C. Jordani, and D. A. G. Gonçalves. 2013. Influência de abordagens biopsicossociais e autocuidados no controle das disfunções temporomandibulares crônicas. Revista Dor 14, 3: 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancaglini, R., E. F. Gherlone, and G. Radaelli. 2001. The relationship of bruxism with craniofacial pain and symptoms from the masticatory system in adult population. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 28, 9: 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delboni, M. E. G., and J. Abrão. 2005. Estudo dos sinais de DTM em pacientes ortodônticos assintomáticos. Dental press Ortodontia e Ortopedia Facial 10, 4: 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnarumma, M. D. C., C. A. Muzilli, C. Ferreira, and K. Nemr. 2010. Disfunções Temporomandibulares: Sinais, sintomas e abordagem multidisciplinar. CEFAC 5, 2: 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, S. F., and L. Le Resche. 1992. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: Review, criteria, examinations and specificarions, critique. Journal Craniomandibular Disorders 6, 4: 301–55. [Google Scholar]

- Epestein, R. M., B. S. Alper, and T. E. Quill. 2004. Communicating evidence for participatory decision making. Journal of the American Medic Association 291, 19: 2359–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frugone Zambra, R. E., and C. Rodríguez. 2003. Bruxismo. Avances en Odontoestomatologia 19, 3: 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaros, A. G., K. Williams, and L. Lausten. 2005. The role of parafunctions, emotions and stress in predicting facial pain. Journal of American Dental Association 136, 4: 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusson, D. G. D. 1998. Bruxismo em crianças. Jornal Brasileiro de Odontopediatria e Odontologia do Bebê 1, 2: 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardini, R. S. R., L. S. R. Ruiz, and M. A. A. Moysés. 2006. Electromyographic analysis of masseter buccinators muscles with pro-fono facial exercises use in bruxers. The Journal of Craniomandibular Practice 24: 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T., N. M. Thie, N. Huynh, S. Miyawaki, and G. J. Lavigne. 2003. Topical review: Sleep bruxism and the role of peripheral sensory influences. Journal of Orofacial Pain 17, 3: 191–213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koyano, K., Y. Tsukiyama, R. Ichiki, and T. Kuwata. 2008. Assessment of bruxism in the clinic. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 35, 7: 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R. J., A. R. Garcia, C. A. S. Garbin, and M. L. M. M. Sundefeld. 2007. Associação entre classe econômica e estresse na ocorrência da disfunção temporomandibular. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiolgia 10, 2: 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheus, R. A., I. R. Ghelardi, D. B. Vega Neto, E. E. Tanaka, S. M. M. Almeida, and A. F. Matheus. 2005. A relação entre os hábitos parafuncionais e a posição do disco articular empacientes sintomáticos para disfunção temporomandibular. Revista Brasileira de Odontologia 62, 1/2: 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, M. H., D. A. C. Maia, A. P. V. Abdon, J. A. Torquato, and F. F. U. Santos Junior. 2014. Escola de posturas pode melhorar a qualidade de vida na disfunção temporomandibular? Cadernos ESP 8, 1: 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Michelotti, A., A. de Wijer, M. Steenks, and M. Farella. 2005. Home-exercises for the management of non-specific temporomandibular disorders. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 32, 11: 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelotti, A., G. Iodice, S. Vollaro, M. H. Steenks, and M. Farella. 2012. Evaluation of the short-term effectiveness of education versus a occlusal splint for the treatment of myofascial pain of the jaw muscles. Journal of the American Dental Association 143, 1: 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, A. R., M. L. Sanches, E. C. Ribeiro, and A. S. Guimarães. 2013. Therapeutic exercises for the control of temporomandibular disorders. Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics 18, 5: 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeson, J. P. 2008. Tratamento das desordens temporomandibulares, 7th ed. Rio de Janeiro. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, K. N. F., L. L. S. Andrade, M. L. G. Costa, and T. F. Portal. 2005. Sinais e sintomas de pacientes com Disfunção Temporomandibular. CEFAC 7, 2: 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R. P. A., W. A. Negreiros, H. C. Scarparo, M. N. Pigozzo, R. L. X. Consani, and M. F. Mesquita. 2006. Bruxismo e qualidade de vida. Odonto ciência 221, 52: 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, R. S., P. A. Oliveira, F. Faot, A. A. B. D. Cury, and R. C. M. R. Garcia. 2008. Prevalência de desordens temporomandibulares e suas associações em jovens universitários. Revista Gaucha de Odontologia 56, 2: 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, I. S. Q., A. F. V. Miranda, V. J. Assencio-Ferreira, and C. Q. M. S. Di Ninno. 2004. Bruxismo: Desempenho da mastigação em adultos jovens. CEFAC 6, 4: 358–362. [Google Scholar]

- Truelove, E., K. H. Huggins, L. Manc, and S. F. Dworkin. 2006. The efficacy of traditional, low-cost and nonsplint therapies for temporomandibular disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Dental Association 137, 8: 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venancio, R. A., C. M. Camparis, and R. F. Z. Lizarelli. 2002. Laser no tratamento de desordens temporomandibulares. Jornal Brasileiro de Oclusão, ATM e dor orofacial 2, 7: 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Versiani, A. H. V., B. M. F. Alves, and A. A. Silva Junior. 2009. O papel das orientações cognitivo comportamentais aos pacientes com dor orofacial-Uma breve revisão. Migrâneas cefaleias 12, 1: 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zarb, G. A., G. E. Carlsson, B. J. Sessle, and N. D. Mohl. 2000. Disfunção na articulação temporomandibular e dos músculos da mastigação. São Paulo: Santos. [Google Scholar]

- Zuanon, A. C. 1999. Bruxismo infantil. Odontologia clínica 9: 41–44. [Google Scholar]

| GENDER | AGE | INITIAL PAIN | AFTER SC PAIN |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | 45 | 1 | 0 |

| M | 53 | 10 | 2 |

| M | 23 | 6 | 2 |

| F | 47 | 8 | 3 |

| F | 29 | 10 | 0 |

| F | 55 | 5 | 4 |

| F | 32 | 5 | 2 |

| F | 20 | 3 | 0 |

| F | 29 | 8 | 5 |

| F | 62 | 8 | 6 |

| F | 59 | 9 | 2 |

| F | 42 | 10 | 7 |

| F | 43 | 10 | 4 |

| F | 44 | 10 | 5 |

| F | 51 | 10 | 4 |

| F | 47 | 10 | 3 |

| F | 45 | 10 | 1 |

| M | 21 | 5 | 3 |

| F | 22 | 10 | 3 |

| F | 59 | 7 | 2 |

| F | 52 | 5 | 0 |

| F | 51 | 10 | 4 |

| F | 68 | 7 | 2 |

| F | 43 | 10 | 6 |

| M | 28 | 8 | 3 |

| F | 48 | 8 | 2 |

| F | 19 | 6 | 1 |

| F | 51 | 10 | 4 |

| F | 47 | 10 | 3 |

| F | 25 | 10 | 3 |

| GENDER | AGE | INITIAL PAIN | PAIN BEFORE 1 MONTH |

|---|---|---|---|

| M | 24 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 60 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 33 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 43 | 10 | 10 |

| M | 70 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 26 | 9 | 9 |

| M | 21 | 6 | 6 |

| F | 27 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 49 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 52 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 65 | 6 | 6 |

| M | 64 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 57 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 21 | 7 | 7 |

| F | 24 | 9 | 9 |

| F | 21 | 7 | 7 |

| F | 22 | 8 | 8 |

| F | 45 | 7 | 7 |

| F | 22 | 8 | 8 |

| F | 25 | 8 | 8 |

| F | 27 | 8 | 8 |

| F | 24 | 7 | 7 |

| F | 25 | 7 | 7 |

| F | 32 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 27 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 24 | 6 | 6 |

| F | 45 | 10 | 10 |

| F | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| F | 34 | 5 | 5 |

| F | 46 | 10 | 10 |

© 2018 by the authors. 2018 Tainara Lopes de Castro Bastos, Rafael de Almeida Spinelli Pinto, Isabela Maddalena Dias, Isabel Cristina Gonçalves Leite, Fabíola Pessôa Pereira Leite

Share and Cite

Bastos, T.L.d.C.; Pinto, R.d.A.S.; Dias, I.M.; Leite, I.C.G.; Leite, F.P.P. Self-Care Treatment on Patients with Wakefulness Bruxism. Int. J. Orofac. Myol. Myofunct. Ther. 2018, 44, 62-74. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2018.44.1.5

Bastos TLdC, Pinto RdAS, Dias IM, Leite ICG, Leite FPP. Self-Care Treatment on Patients with Wakefulness Bruxism. International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy. 2018; 44(1):62-74. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2018.44.1.5

Chicago/Turabian StyleBastos, Tainara Lopes de Castro, Rafael de Almeida Spinelli Pinto, Isabela Maddalena Dias, Isabel Cristina Gonçalves Leite, and Fabíola Pessôa Pereira Leite. 2018. "Self-Care Treatment on Patients with Wakefulness Bruxism" International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy 44, no. 1: 62-74. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2018.44.1.5

APA StyleBastos, T. L. d. C., Pinto, R. d. A. S., Dias, I. M., Leite, I. C. G., & Leite, F. P. P. (2018). Self-Care Treatment on Patients with Wakefulness Bruxism. International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy, 44(1), 62-74. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2018.44.1.5