Abstract

INTRODUCTION: Some proposals of myofunctional therapy directed to individuals undergoing orthognathic surgery have been presented which promote the orofacial myofunctional balance, enhancing the treatment stability. OBJECTIVE: To verify the effect of myofunctional therapy on orofacial functions and quality of life in individuals undergoing orthognathic surgery. METHOD: A total of 24 individuals, with mean age of 26.5 years, participated in the study. They were divided into two groups, namely with myofunctional therapy (N=12) and without myofunctional therapy (N=12). Breathing, chewing, swallowing, and speech were evaluated from tests established by the MBGR Orofacial Myofunctional Evaluation, using the scores specified in the protocol. The quality of life (QL) was evaluated using the Oral Health Impact Profile-OHIP-14 questionnaire, which comprises 14 questions that measure the individual´s perception of the impact of their oral conditions on their well-being in recent months. The evaluations were carried out before and 3 months after orthognathic surgery. The myofunctional therapy was initiated 30 days after surgery, with exercises aimed at improving orofacial mobility, tone and sensitivity, as well as the training of normal physiological patterns of orofacial functions. The comparisons between orofacial functions and the study groups were verified by the Mann-Whitney test, using a significance level of 5%. RESULTS: After surgery, the individuals without myofunctional therapy presented with an improvement in breathing and oral health-related quality of life (p<0.05), while in the group undergoing myofunctional therapy there was improvement in all aspects investigated (p<0.05). Comparison between the study groups showed better performance in breathing (p=0.002), chewing (p=0.012), swallowing (p=0.002) and speech (0.034) in individuals who underwent myofunctional therapy. CONCLUSION: The orthognathic surgery alone improved breathing and quality of life. However, the surgical procedure associated with myofunctional treatment, besides improving all oral functions investigated and quality of life, provided better functional performance in breathing, chewing, swallowing and speech. This study’s participants demonstrated the effectiveness of the orofacial myofunctional intervention.

Keywords:

orthognathic surgery; quality of life; breathing; speech; chewing; swallowing; myofunctional therapy INTRODUCTION

Dentofacial deformity (DFD) results in alterations of facial esthetics and harmony, and can cause psychological, social and professional problems for patients, with consequences in their quality of life (Ambrizzi, Franzi, Pereira Filho, Gabrielli, Gimenez, & Bertoz, 2007; Ribas, Reis, França, & Lima, 2005). In addition, DFD determines specific myofunctional characteristics, peculiar to the type of disproportion, such as alterations in the habitual posture of lips and tongue, muscle asymmetries, temporomandibular dysfunctions (TMD), deviations in chewing, swallowing, speech, and breathing (Egemark, Blomqvist, Cromvik, & Isaksson, 2000). After surgical correction and correct tooth positioning, in some cases, the soft tissues restructure appropriately with a good functional response. However, for other individuals, after orthognathic surgery there is maintenance or onset of altered function patterns, which can negatively impact the dental treatment (Marchesan, & Bianchini, 1999; Ribeiro, 1999; Pacheco, 2000; Sígolo, Campiotto, & Sotelo, 2009). In this regard, studies have described some intervention proposals aimed at individuals undergoing orthognathic surgery within interdisciplinary teams (Ribeiro, 1999; Varandas, Campos, & Motta, 2008), with the objective of promoting orofacial myofunctional balance, enhancing the stability of final treatment results.

Gallerano, Ruoppolo & Silvestri (2012) demonstrated the importance of a rehabilitation protocol for the orofacial functions after orthognathic surgery, aimed at achieving long-term success in 19 patients. Following rehabilitation of the functional parameters, 12 patients fully adapted the orofacial functions, 5 did it partially, and two had an inefficient treatment. The authors concluded that the interdisciplinary approach is necessary to adapt all functions that are not compatible with the structural changes and may lead to recurrence (Gallerano, Ruoppolo, & Silvestri , 2012).

The need to assess the quality of life of individuals with dental/skeletal malocclusion is related to the importance of facial and dental esthetics in people´s lives and the way they self-evaluate their facial condition (Feu, Oliveira, Oliveira Almeida, Kiyak, & Miguel, 2010). The same malocclusion can be perceived differently by different people, and their individual perception is probably the key to the search for orthodontic treatment, rather than related or not to the severity of the malocclusion (Oliveira, & Sheiham, 2004). In a literature review, 21 published papers were located, which showed that the individuals improved their quality of life after orthognathic surgery, and each individual presented different motivations and expectations regarding the treatment (Soh, & Narayanan, 2013). However, no research was located that investigated the impact of orofacial myofunctional conditions on the quality of life after surgery.

Alterations in orofacial functions, as well as on the quality of life in patients with dentofacial deformity, are reported in the literature.

Nevertheless, few studies address the result of myofunctional treatment for such cases. Thus, this study aimed at verifying the effect of myofunctional therapy on the orofacial functions and quality of life of individuals undergoing orthognathic surgery.

METHOD

The research project was approved by the Institutional Review Board under process no. 049/2009. All individuals in the sample signed a Consent Form and their records were analyzed.

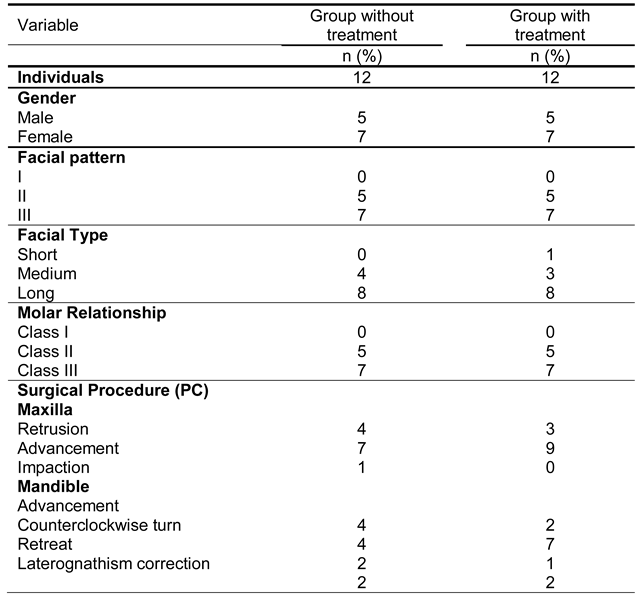

The study was conducted on 24 individuals (14 females and 10 males), in the age range 18-40 years (mean=26.38), divided into two groups, the myofunctional therapy group (n=12) and no myofunctional therapy group (n=12). Table 1 shows the data on gender, facial pattern, molar ratio and surgical procedure carried out for the participants.

Table 1.

Distribution of individuals according to gender and facial pattern of the DFD Group and Control Group.

All participants were assessed as to their orofacial myofunctional condition and quality of life, prior to and 3 months following orthognathic surgery. The orofacial functions were evaluated by the MBGR Orofacial Myofunctional Evaluation Protocol (Marchesan, Berretin-Felix, & Genaro, 2012) and the scores attributed are specified in the protocol itself, zero value being considered as appropriate and higher values as altered. Thus, the higher the score, the worse the performance. In breathing (scores 0-9), the mode, type, and possibility of nasal use was verified. In chewing (scores 0-10), using a wafer biscuit as food, the chewing pattern (alternate or simultaneous bilateral, chronic or preferentially unilateral), were verified. In addition the presence or absence of muscle contractions that were not expected were noted. In swallowing (scores 0-50), the directed swallowing of solid food (wafer biscuit) and liquid (water) was verified. This included: lip seal, tongue posture, lower lip posture, food containment, orbicularis and mentalis muscle contraction, head movement, and swallowing coordination. In speech (scores 0-32), using a sample of spontaneous speech, counting numbers from zero to 20, and naming of pictures proposed by the protocol, the following characteristics were analyzed: mouth opening, tongue position, lip and mandibular movement, resonance, speed and pneumophonoarticulatory coordination, as well as omissions, substitutions, distortions or articulatory inaccuracy.

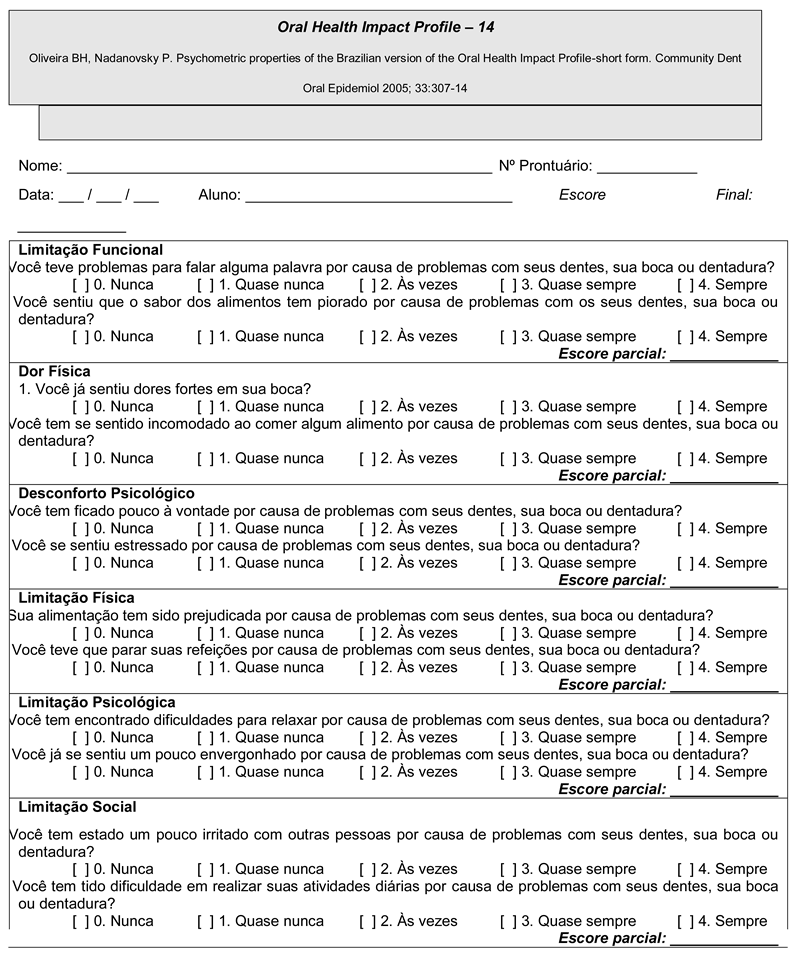

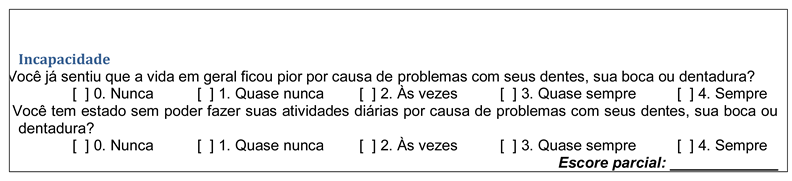

To assess the quality of life (QL), we used the Brazilian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile-OHIP-14 questionnaire (Appendix A) (Oliveira, & Nadanovsky, 2005), translated and validated from the original protocol (Slade, 1997), which comprises 14 questions that measure the individuals’ perception on the impact of their oral conditions on their well-being in recent months. The total score obtained corresponded to the sum of scores of all the questions; the maximum individual answer was represented by 56 points. The higher the scores obtained, the worse the orofacial functions and the QL.

The orofacial myofunctional therapy was initiated 40 days after the surgical procedure. Meetings were held every week, totaling between 8 and 15 sessions. The following aspects were addressed: tactile-kinesthetic and thermal stimulation in the lower facial third; exercises of lips, tongue and mandible mobility; exercises to adjust the tone of tongue, lips, cheeks and mentum, as well as to improve the morphological aspects of the lips (shortened upper lip and everted lower lip); functional training to adjust the habitual position of the mandible, lips and tongue, as well as breathing functions (improvement in sinus aeration, stimulation of nasal breathing, medium lower respiratory tract training); chewing (alternate or simultaneous bilateral chewing pattern); swallowing (regarding the function of lips and tongue); phonetic aspects of speech (regarding the function of tongue and articulatory pattern); as well as the expressiveness during oral communication, aiming at maintenance of the orofacial and esthetic functional balance. The results obtained in the evaluations were written in specific protocols and transcribed into the EXCEL software. Comparisons between the orofacial functions and the study groups were verified by the Mann-Whitney test, using a significance level of 5%.

RESULTS

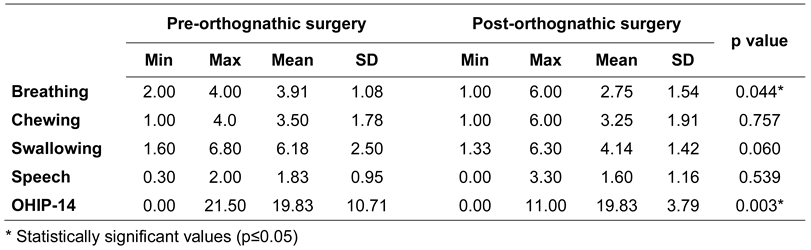

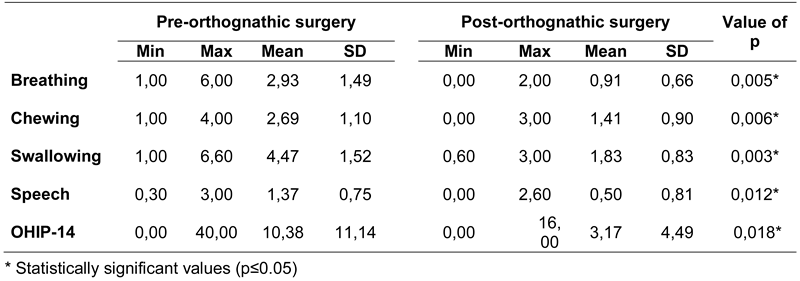

Analysis of the effect of orthognathic surgery after three months revealed that individuals without myofunctional therapy showed improvement in breathing function (p=0.044) and quality of life (p=0.003). Otherwise, no changes in chewing, swallowing and speech were verified, as shown in Table 2. Significant difference (p≤0.05) was observed in all orofacial functions (breathing, chewing, swallowing and speech) and in oral health-related quality of life for individuals submitted to myofunctional therapy, when comparing the results before and after orthognathic surgery (Table 3). This indicated that the orofacial myofunctional therapy brought benefits to all orofacial functions studied.

Table 2.

Minimum and maximum values, mean, standard deviation and p values of scores obtained for the orofacial functions (MBGR protocol), and scores of quality of life (OHIP-14 protocol) before and 3 months after orthognathic surgery for the group without myofunctional therapy.

Table 3.

Minimum and maximum values, mean, standard deviation and p values of scores obtained for the orofacial functions (MBGR protocol) and scores of quality of life (OHIP-14 protocol) before and 3 months after orthognathic surgery for the group receiving orofacial myofunctional therapy

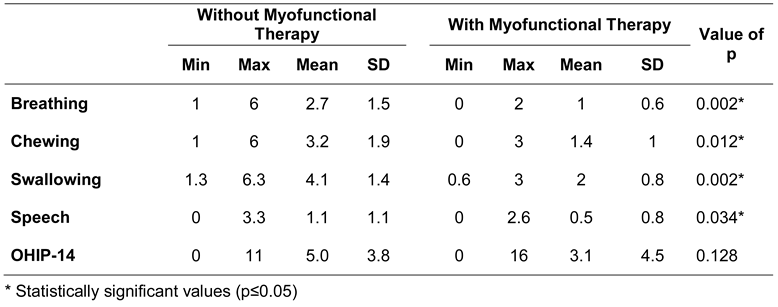

Comparison between the different study groups for the postoperative results is presented in Table 4. A significant reduction in scores was obtained for all orofacial functions (breathing, chewing, swallowing and speech), with better performance for individuals undergoing the orofacial myofunctional therapy, in comparison to individuals without myofunctional intervention. The quality of life scores showed no difference between groups.

Table 4.

Minimum and maximum values, mean, standard deviation and p values of scores obtained for the orofacial functions (MBGR protocol) and scores of quality of life (OHIP-14 protocol) 3 months after orthognathic surgery for the different study groups (with and without myofunctional therapy).

DISCUSSION

This research considered the impact of myofunctional therapy associated with orthognathic surgery in the performance of orofacial functions, as well as in the oral health-related quality of life in individuals with DFD.

The improvement in breathing function after orthognathic surgery, for both groups, can be justified by the increase of the nasal air space due to the surgical procedure performed. In this research, the surgeries for correction of DFD were bi-maxillary, maybe involving maxillary advancement, mandibular advancement and mandibular counterclockwise rotation, besides other procedures. The literature showed that maxillary expansion produced an increase in nasal permeability, which did not persist over time, and the changes related to the respiratory pattern varied (Berretin-Felix, Yamashita, Nary Filho, Gonçales, Trindade, & Trindade, 2006). Studies which assessed three-dimensionally changes occurring in the pharyngeal air space after maxillary and mandibular advancement showed a significant increase in air space after orthognathic surgery, reducing the risks of respiratory disorders (Abramson, Susarla, Lawler, Bouchard, Troulis, & Kaban, 2011; Fairburn, Waite, Vilos, Harding, Bernreuter, Cure, & Cherala, 2007; Hernàndez-Alfaro, Guijarro-Martìnez & Mareque-Bueno, 2011; Marşan, Vasfi Kuvat, Öztaş, Süsal, & Emekli, 2009).

The lack of change in orofacial functions of chewing, swallowing and speech, in the group without myofunctional therapy after orthognathic surgery, can be attributed to maintenance of the presurgical adaptive functional patterns, due to the skeletal malocclusion presented by individuals (Berwig, Ritzel, Silva, Mezzomo, Côrrea, & Serpa, 2015; Coutinho, Abath, Campos, Antunes, & Carvalho, 2009; Egemark, Blomqvist, Cromvik, Isakson, 2000; Migliorucci, Sovinski, Passos, Bucci, Salgado, Nary Filho, Abramides, & Berretin-Felix, 2015; Zupo, Benedicto, Kairalla, Miranda, Cesar, & Paranhos, 2011). Thus, although the corrections of skeletal disproportions are successful, there are cases of bone and/or functional relapse due to reduced time of blockage, and subsequent lack of adaptation of the oral muscle and structures to the new intraoral configuration (Marchesan, & Bianchini, 1999).

On the other hand, for individuals who received orofacial myofunctional therapy, the statistical analysis showed lower scores in breathing, chewing, swallowing and speech, beyond the quality of life, after orthognathic surgery.

Although there are few published studies on the effectiveness of myofunctional therapy for the orofacial functions in the literature, in general, researchers have reported that the orofacial myofunctional intervention has shown to be efficient for rehabilitation in cases of oral breathing (Corrêa, & Bérzin, 2007; Gavishi, & Winocur, 2006; Guisti Braislin, & Cascella, 2006; Hellmann, Giannakopoulos, Blaser, Eberhard, & Schindler, 2011; Smithpeter, & Covell, 2010; Marson, Tessitore, Sakano, & Nermr, 2012; Saccomanno, Antonini, Alatri, D’Angelantonio, Fiorita, & Deli, 2012), as well as in masticatory dysfunction (Corrêa, & Bérzin, 2007; Hellmann, Giannakopoulos, Blaser, Eberhard, & Schindler, 2011; Kijak, Lietz-Kijak, Sliwinski, & Fraczak, 2013; Maffei, Garcia, Biase, Souza Camargo, Vianna-Lara, Grégio, & Azevedo-Alanis, 2014), Marson, Tessitore, Sakano, & Nermr, 2012; Richardson, Gonzalez, Crow, & Sussman, 2012; Shibuya, Ishida, Kobayashi, Hasegawa, Nibu, & Komori, 2013); atypical swallowing (Degan, & Pyppin-Rontani, 2005; Richardson, Gonzalez, Crow, & Sussman, 2012) and phonetic speech disorders (McAulifffe, & Cornwrll, 2008), corroborating the present study.

Specifically regarding the masticatory function, the present results are similar to those shown in the literature, since one study also verified the effectiveness of a rehabilitation program for chewing in individuals undergoing orthognathic surgery, with significant improvement in mandibular mobility and functional performance (Mangilli, 2012). In the study carried out by Pereira & Bianchini (2011), after surgical correction and myofunctional therapy, adjustment of chewing was verified in 68% of the sample, similar results as the present study. Besides, the morphological characteristics of the masticatory muscles which may also be influenced by the surgical-orthodontic treatment associated with myofunctional therapy, another study published by Trawitzki (2011) found an increase in the thickness of masseter muscles in individuals with skeletal Class III, three years after orthognathic surgery. However, such aspects were not considered in the present study, hindering comparisons.

This study also observed improvement in swallowing for individuals who had myofunctional therapy, as reported by Pereira & Bianchini (2011), who observed adequate function in 92% of the sample following post-surgical myofunctional treatment. This study also supported findings that corroborate with another study, in which the association of surgical and speech therapy treatments resulted in the adjustment of functional patterns, and swallowing which demonstrated an improvement of the functions and presented better results with myofunctional therapy (Pereira, & Bianchini, 2011).

The impact of orofacial myofunctional therapy on speech after orthognathic surgery, in the present study, was similar to the study of Pereira & Bianchini (2011), which verified an adjustment of speech in 88% of the sample. Similarly, they also found a significant improvement in the speech function in 83% of individuals studied, with correction of anterior and lateral mandibular deviation, phonetic distortions, anterior tongue interposition and hyperfunction of the perioral muscles, following the myofunctional intervention post-surgery.

Comparison between groups with and without myofunctional treatment, three months after orthognathic surgery, showed lower scores for the orofacial functions in the group submitted to myofunctional treatment, i.e. better functional performance for breathing, chewing, swallowing and speech. Thus, this result shows the importance of myofunctional therapy for the integration of oral functions, considering the need of muscle re-education after orthognathic surgery, as described in the literature (Trawitzki, Dantas, Elias-Junio, & Mello-Filho, 2011).

The presence of better oral health-related quality of life scores after orthognathic surgery in both groups studied, regardless of the myofunctional therapy intervention, agrees with many authors who demonstrated the positive effects of orthognathic surgery on the quality of life (Dantas, Neto, Carvalho, Martins, Souza, & Sarmento, 2015; Miguel, Palomares, & Feu, 2014; Naini, Cobourne, McDonald, & Wertheim, 2015; Raffaini, & Pisani, 2015; Sho, & Narayanan, 2013). The results revealed that the facial reconstructive and esthetic surgical interventions improved the perception of body image and self-esteem with positive effects on the emotional, social and mental aspects, being efficient in improving the self-confidence and quality of life of these individuals. The performance of orofacial functions was expected to impact the quality of life in oral health, although this hypothesis was not confirmed. A possible explanation for this finding can be attributed to the characteristics of the protocol applied, which includes few questions that address aspects associated with others, related to feeding or communication.

This was the first study to compare the orofacial functions in two groups of participants with and without myofunctional therapy after orthognathic surgery. The findings showed that the orofacial myofunctional therapist plays an important role in the orthognathic surgery team, seeking the reorganization of muscle activity, which is necessary for the integration of orofacial functions following dentofacial adjustment. Further research must be developed with a larger sample using controlled and randomized, blind studies which includes longitudinal follow-up of patients.

CONCLUSION

Orofacial myofunctional therapy yielded better results in breathing, chewing, swallowing and speech for the individuals who underwent orthognathic surgery than the surgical procedure alone, which was associated with improved breathing and the oral health-related quality of life. This demonstrated the effectiveness of orofacial myofunctional therapy for the participants in this study.

Appendix A

References

- Abramson, Z.; Susarla, S. M.; Lawler, M.; Bouchard, C.; Troulis, M.; Kaban, L. B. Three-dimensional computed tomographic airway analysis of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated by maxillomandibular advancement. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2011, 69, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aléssio, C. V.; Mezzomo, C. L.; Körbes, D. Intervenção Fonoaudiológica nos casos de pacientes classe III com indicação à Cirurgia Ortognática. Arquivos em Odontologia 2007, 43, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrizzi, D. R.; Franzi, S. A.; Pereira Filho, V. A.; Gabrielli, M. A. C.; Gimenez, C. M. M.; Bertoz, F. A. Avaliação das queixas estético-funcionais em pacientes portadores de deformidades dentofaciais. Revista Dental Press de Ortodontia e Ortopedia Facial 2007, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Berlese, D. B.; Copetti, F.; Weimmann, A. R. M.; Ferreira, P. F.; Haefffner, L. S. B. Revista CEFAC 2013, 15, 913–921. [CrossRef]

- Berretin-Felix, G.; Yamashita, R. P.; Nary Filho, H.; Gonçales, E. S.; Trindade, A. S.; Trindade, I. E. Short- and long-term effect of surgically assisted maxillary expansion on nasal airway size. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2006, 17, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwig, L. C.; Ritzel, R. A.; Silva, A. M. T.; Mezzomo, C. L.; Côrrea, E. C. R.; Serpa, E. O. Posição habitual da língua e dos lábios nos padrões de crescimento anteroposterior e vertical. Revista CEFAC 2015, 17, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, E. C.; Bérzin, F. Efficacy of physical therapy on cervical muscle activity and on body posture in school-age mouth breathing children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2007, 71, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, T. A.; Abath, M. B.; Campos, G. J. L.; Antunes, A. A.; Carvalho, R. W. F. Adaptações do sistema estomatognático em indivíduos com codesproporções maxilo-mandibulares: Revisão da literatura. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Fonoaudiologia 2009, 14, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, J. F. C.; Neto, J. N. N.; Carvalho, S. H. G.; Martins, I. M. C. L.; Souza, R. F.; Sarmento, V. A. Satisfaction of skeletal class III patients treated with different types of orthognathic surgery. International Journal of oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2015, 44, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degan, V. V.; Puppin-Rontani, R. M. Remoção de hábitos e terapia miofuncional: Restabelecimento da deglutição e repouso lingual. Pró-Fono Revista de Atualização Científica 2005, 17, 375–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egemark, I.; Blomqvist, J. E.; Cromvik, U.; Isaksson, S. Temporomandibular dysfunction in patients treated with orthodontics in combination with orthognathic surgery. The European Journal of Orthodontics 2000, 22, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, S. C.; Waite, P. D.; Vilos, G.; Harding, S. M.; Bernreuter, W.; Cure, J.; Cherala, S. Three dimensional changes in upper airways of patients with obstructive sleep apnea following maxillomandibular advancement. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2007, 65, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feu, D.; Oliveira, B. H.; Oliveira Almeida, M. A.; Kiyak, H. A.; Miguel, J. A. Oral health-related quality of life and orthodontic treatment seeking. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2010, 138, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, J. A.; Vasconcellos, R. J. H. Acompanhamento fonoaudiológico pré e pós-cirurgia ortognática: Relato de caso. Revista Da Sociedade Brasileira De Fonoaudiologia 2008, 13, 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Gallerano, G.; Ruoppolo, G.; Silvestri, A. Myofunctional and speech rehabilitation after orthodontic-surgical treatment of dento-maxillofacial dysgnathia. Progress in Orthodontics 2012, 13, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavish, A.; Winocur, E.; Astandzelov-Nachmias, T.; Gazit, E. Effect of controlled masticatory exercise on pain and muscle performance in myofascial pain patients: A pilot study. Cranio 2006, 24, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisti Braislin, M. A.; Cascella, P. W. A preliminary investigation of the efficacy of oral motor exercises for children with mild articulation disorders. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2005, 28, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, D.; Giannakopoulos, N. N.; Blaser, R.; Eberhard, L.; Rues, S.; Schindler, H. J. Long-term training effects on masticatory muscles. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2011, 38, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alfaro, F.; Guijarro-Martínez, R.; Mareque-Bueno, J. Effect of mono- and bimaxillary advancement on pharyngeal airway volume: Cone beam computed tomography evaluation. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2011, 69, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijak, E.; Lietz-Kijak, D.; Sliwiński, Z.; Frączak, B. Muscle activity in the course of rehabilitation of masticatory motor system functional disorders. Postępy Higieny i Medycyny Doświadczalnej 2013, 27, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, A. P. Interlandi, Ortodontia, S., Eds.; Introdução ao problema da deglutição atípica. In Bases para a iniciação. Artes Médicas.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Maffei, C.; Garcia, P.; de Biase, N. G.; de Souza Camargo, E.; Vianna-Lara, M. S.; Grégio, A. M.; Azevedo-Alanis, L. R. Orthodontic intervention combined with myofunctional therapy increases electromyographic activity of masticatory muscles in patients with skeletal unilateral posterior crossbite. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 2014, 72, 298–303. [Google Scholar]

- Mangilli, L. D. Programa de avaliação e tratamento fonoaudiológico para a reabilitação da função mastigatória de indivíduos submetidos à cirurgia ortognática por deformidade dentofacial; Tese a ser apresentada à Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marchesan, I. Q.; Bianchini, E. M. G. Araújo, M. C. A., Ed.; A fonoaudiologia e a cirurgia ortognática. In Cirurgia ortognática; São Paulo, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M. C. Atuação fonoaudiológica no pré e pós-operatório em cirurgia ortognática. J Bras Fonoaudiol 1999, 1, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Marchesan, I. Q.; Berretin-Félix, G.; Genaro, K. F. MBGR protocol of orofacial myofunctional evaluation with scores. The International Journal of Orofacial Myology 2012, 38, 38–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marşan, G.; Vasfi Kuvat, S.; Öztaş, E.; Cura, N.; Süsal, Z.; Emekli, U. Oropharyngeal airway changes following bimaxillary surgery in Class III female adults. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 2009, 37, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshalla, P. Horns, whistles, bite blocks, and straws: A review of tools/objects used in articulation therapy by Van Riper and other traditional therapists. The International Journal Of Orofacial Myology 2011, 37, 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Marson, A.; Tessitore, A.; Sakano, E.; Nemr, K. Efetividade da fonoterapia e proposta de intervenção breve em respiradores orais. Revista CEFAC 2012, 14, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, M. J.; Cornwell, P. L. Intervention for lateral /s/ using electropalatography (EPG) biofeedback and an intensive motor learning approach: A case report. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 2008, 43, 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Migliorucci, R. R.; Sovinski, S. R. P.; Passos, D. C. B. O. F.; Bucci, A. C.; Salgado, M. H.; Nary Filho, H.; Abramides, D. V. M.; Berretin-Felix, G. Funções orofaciais e qualidade de vida em saúde oral em indivíduos com deformidade dentofacial. CoDAS 2015, 27, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miguel, J. A.; Palomares, N. B.; Feu, D. Life-quality of orthognathic surgery patients: The search for an integral diagnosis. Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics 2014, 19, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naini, F. B.; Cobourne, M. T.; McDonald, F.; Wertheim, D. The aesthetic impact of upper lip inclination in orthodontics and orthognathic surgery. The European Journal of Orthodontics 2015, 37, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurminen, L.; Pietila, T.; Vinkka-Puhakka, H. Motivation for and satisfaction with orthodontic-surgical treatment: A retrospective study of 28 patients. The European Journal of Orthodontics 1999, 21, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B. H.; Nadanovsky, P. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile–short form. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 2005, 33, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C. M.; Sheiham, A. Orthodontic treatment and its impact in oral health-related quality of life in Brazilian adolescents. J Orthod 2004, 31, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, V. S. Cirurgia ortognática: Uma abordagem fonoaudiológica. Revista CEFAC 2000, 2, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, J. B. A.; Bianchini, E. M. G. Caracterização das funções estomatognáticas e disfunções temporomandibularespré e pós cirurgiaortognática e reabilitação fonoaudiológica da deformidade dentofacial classe II esquelética. Revista CEFAC 2011, 13, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaini, M.; Pisani, C. Orthognathic surgery with or without autologous fat micrograft injection: Preliminary report on aesthetic outcomes and patient satisfactionOriginal Research Article. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2015, 44, 143–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, M. O.; Reis, L. F. G.; França, B. H. S.; Lima, A. A. S. Cirurgia ortognática: Orientações legais aos ortodontistas e cirurgiões bucofaciais. Revista Dental Press de Ortodontia e Ortopedia Facial 2005, 10, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, K.; Gonzalez, Y.; Crow, H.; Sussman, J. The effect of oral motor exercises on patients with myofascial pain of masticatory system. Case series report. The New York State Dental Journal 2012, 78, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Saccomanno, S.; Antonini, G.; Alatri, L.; D’Angelantonio, M.; Fiorita, A.; Deli, R. Patients treated with orthodontic-myofunctional therapeutic protocol. European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 2012, 13, 241–243. [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya, Y.; Ishida, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Nibu, K.; Komori, T. Evaluation of masticatory function after maxillectomy using a colour-changing chewing gum. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2013, 40, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sígolo, C.; Campiotto, A. R.; Sotelo, M. B. Posição habitual de língua e padrão de deglutição em indivíduo com oclusão classe III, pré e pós-cirurgia ortognática. Revista CEFAC 2009, 11, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithpeter, J.; Covell, D., Jr. Relapse of anterior open bites treated with orthodontic appliances with and without orofacial myofunctional therapy. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2010, 137, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, C. L.; Narayanan, V. Quality of life assessment in patients with dentofacial deformity undergoing orthognathic surgery—A systematic review. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery 2013, 42, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trawitzki, L. V.; Dantas, R. O.; Elias-Júnior, J.; Mello-Filho, F. V. Masseter muscle thickness three years after surgical correction of class III dentofacial deformity. Archives of Oral Biology 2011, 56, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varandas, C. P. M.; Campos, L. G.; Motta, A. R. Adesão ao tratamento fonoaudiológico segundo a visão de ortodontistas e odontopediatras. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Fonoaudiologia 2008, 13, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermark, A.; Shayeghi, F.; Thor, A. Temporomandibular dysfunction in 1516 patients before and after orthognathic surgery. The International Journal of Adult Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery 2001, 16, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wolford, I. M.; Reiche-Fischel, O.; Mehra, P. Changes in temporomandibular joint dysfunction after orthognathic surgery. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2003, 6, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupo, D. G.; Benedicto, E. N.; Kairalla, S. A; Miranda, S. L.; Cesar, C. P. H. A. R.; Paranhos, L. R. Características morfológicas e o tratamento ortodôntico para o padrão III facial. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Craniomaxilofacial 2011, 14, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the author. 2017 Renata Resina Migliorucci, Dagma Venturini Marques Abramides, Raquel Rodrigues Rosa, Marco Dapievi Bresaola, Hugo Nary Filho, Giédre Berretin-Felix