Effects of Eimeria Challenge and Monensin Supplementation on Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, and Intestinal Health of Broilers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Performance and Nutrient Digestibility

2.3. Oocysts Counting

2.4. Histopathological Scoring and Intestinal Morphometry

2.5. RNA Extraction

2.6. cDNA Synthesis and Gene Expression Analysis

| Gene | Sequence | Reference | Accession Number/GenBank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxanthine Phophoribosyl-Transferase | F: CCCAAACATTATGCAGACGA | [32] | AJ132697 |

| R: TGTCCTGTCCATGATGAGC | |||

| Ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 | F: TTGTTCATCACCACAAGATT | [33] | NM_204987 |

| R: CCCATTGTCTCCGGTCTTAA | |||

| Zonula Occludens-A | F: CCGCAGTCGTTCACGATCT R: GGAGAATGTCTGAATGGTCTGA | [34] | XM_04689952 |

| Zonula Occludens-B | F: GCCCAGCAGATGGATTACTT R: TGGCCACTTTTCCACTTTTC | [34] | AC192784 |

| Junctional Adhesion Molecule | F: AGACAGGAACAGGCAGTGCT R: TCCAATCCCATTTGAGGCTA | [34] | NM_001397141 |

| Occludin | F: ACGGCAAAGCCAACATCTAC R: ATCCGCCACGTTCTTCAC | [34] | NM_205128 |

| Mucin 2 | F: AGGAATGGGCTGCAAGAGAC R: GTGACATCAGGGCACACAGA | [35] | XM 001234581.3 |

| Glucose transporter 2 | F: GAAGGTGGAGGAGGCCAAA R: TTTCATCGGGTCACAGTTTCC | [36] | NM_207178.1 |

| Sugar transporter 1 | F: TCAGGTCTACCTGTCAATCC R: GAGAATGAAAGATCCCACAA | [37] | NM_001293240.1 |

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

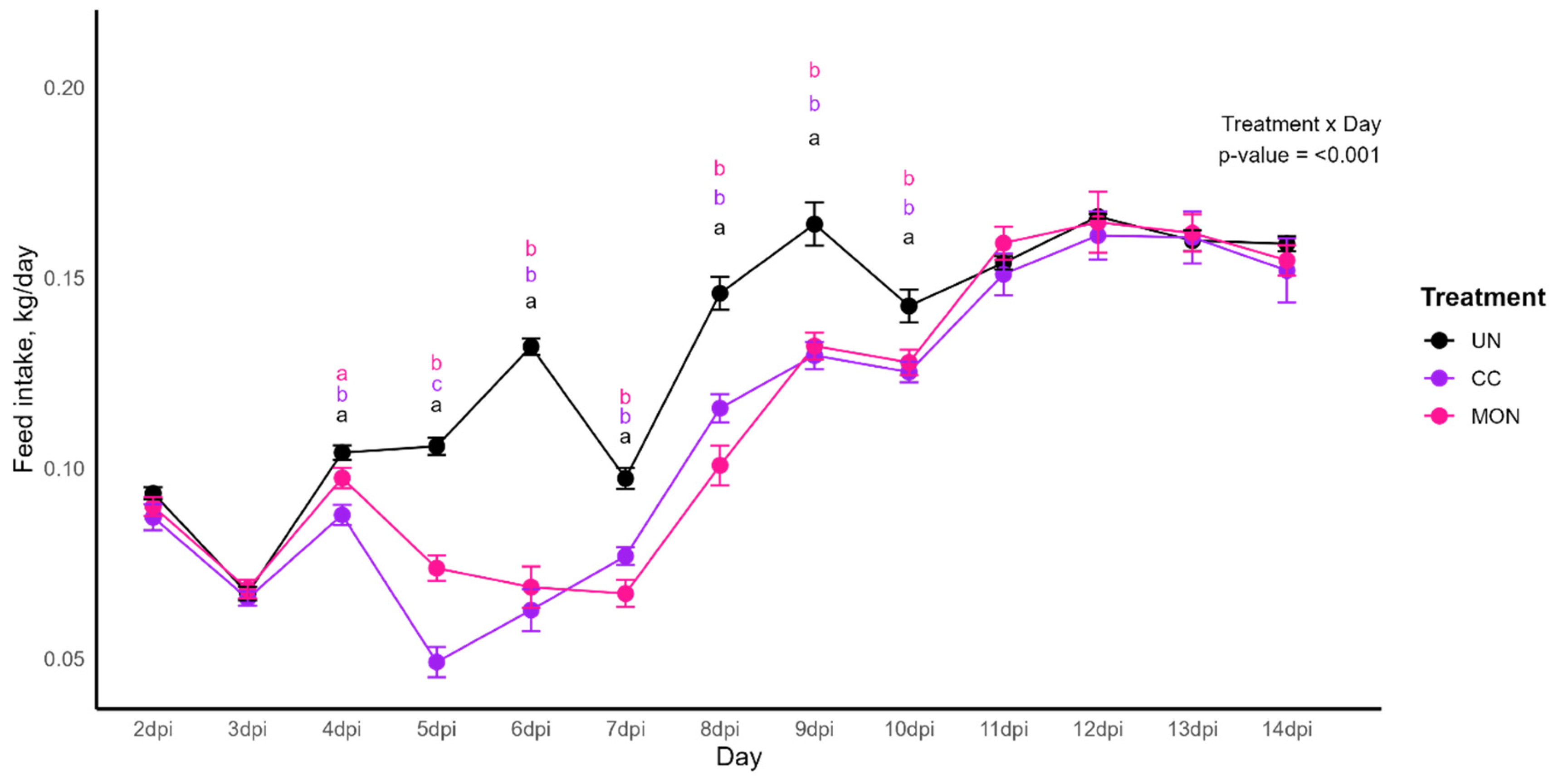

3.1. Body Weight Gain, Feed Intake, Feed Conversion Ratio and Body Weight

3.2. Nutrient Digestibility and Metabolizable Energy

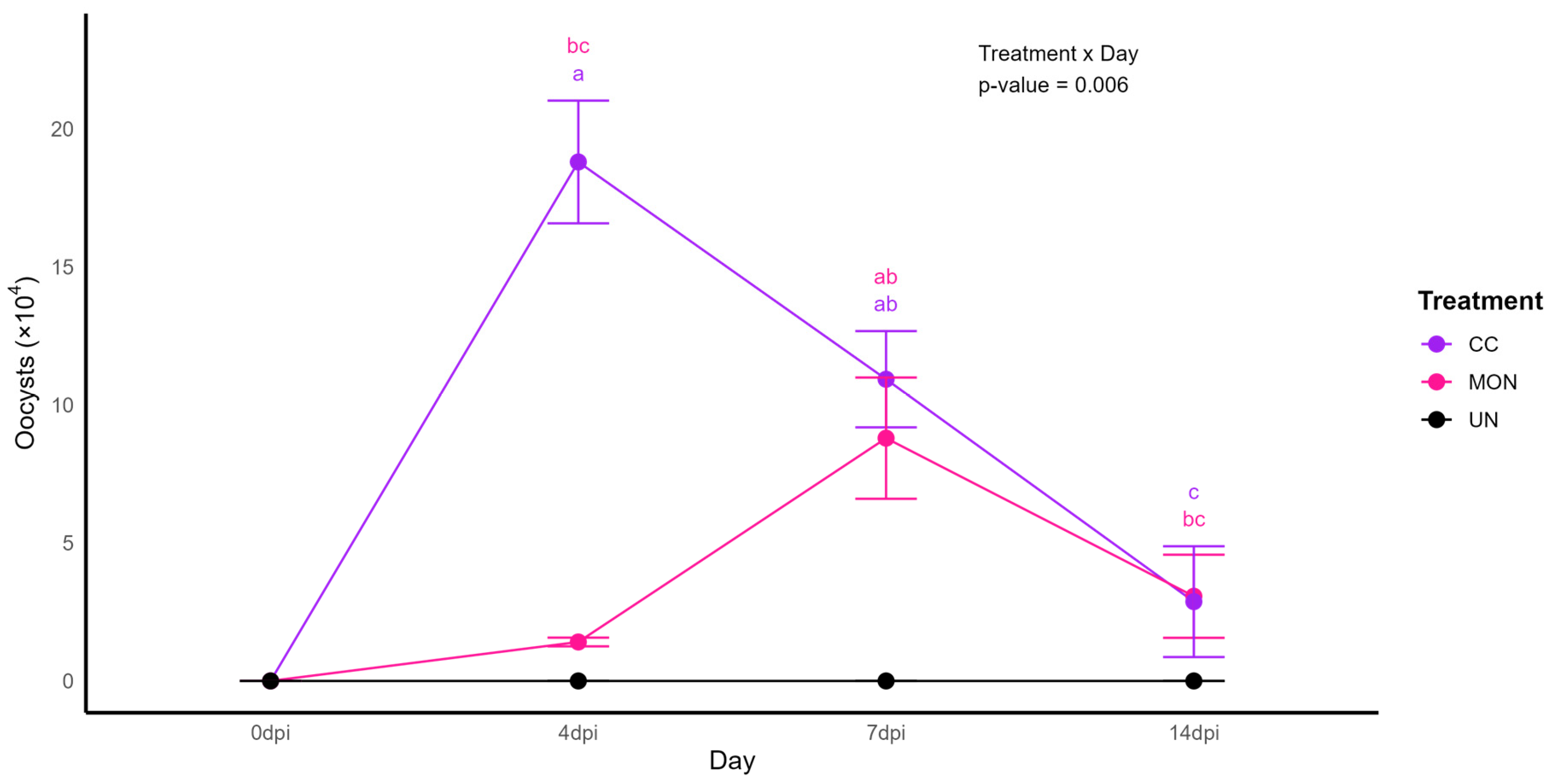

3.3. Oocysts Shedding

3.4. Intestinal Morphometry of the Duodenum and Jejunum

3.5. Intestinal Health Index (“I See Inside”)

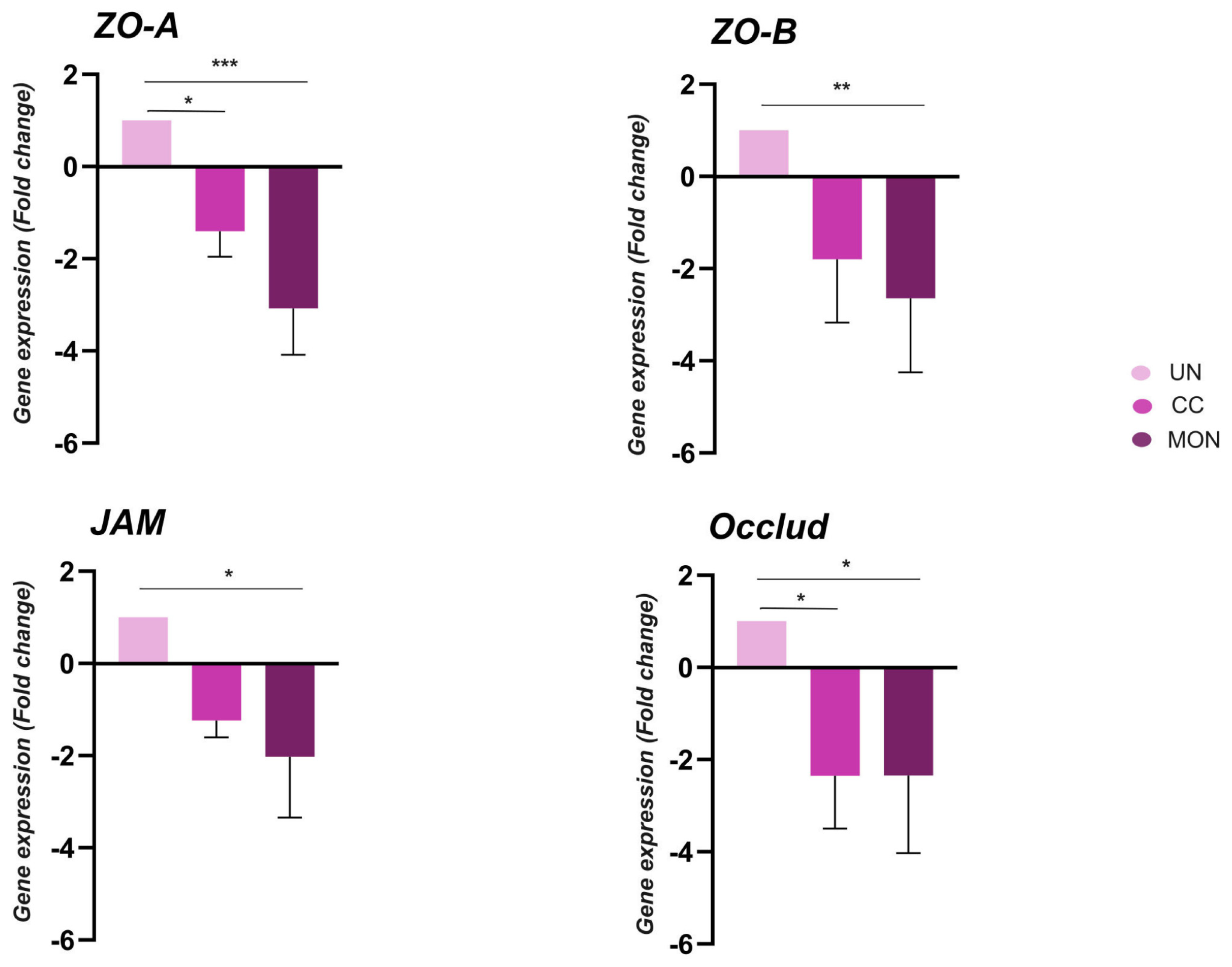

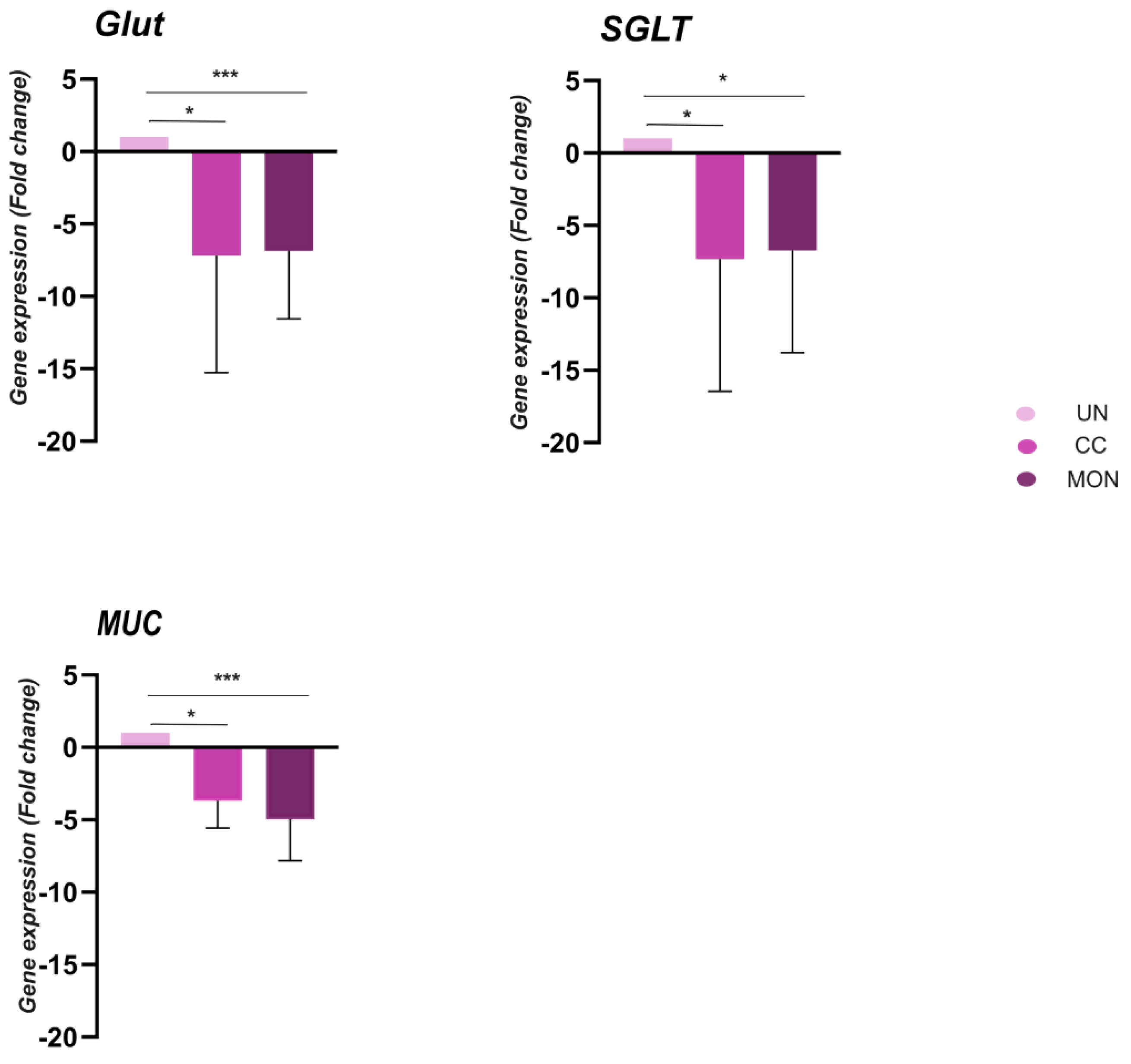

3.6. Gene Expression in Duodenum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGPs | Antimicrobial Growth-Promoters |

| AME | Apparent Metabolizable Energy |

| AMEn | Nitrogen-Corrected Apparent Metabolizable Energy |

| ATTD | Apparent Total Tract Digestibility |

| BW | Body Weight |

| BWG | Body Weight Gain |

| CEUA | Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals |

| CP | Crude Protein |

| DM | Dry Matter |

| dpi | Days Post-Infection |

| FCR | Feed Conversion Ratio |

| FI | Feed Intake |

| GE | Gross Energy |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| HPRT | Hypoxanthine Phophoribosyl-Transferase |

| ISI | I See Inside |

| JAM | Junctional Adhesion Molecule |

| MUC2 | Mucin 2 |

| NB | Nitrogen Balance |

| NE | Necrotic Enteritis |

| OCLN | Occludin |

| OM | Organic Matter |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| Vh:Cd | Villus Height-to-Crypt Depth |

| WG | Weight Gain |

| ZO-A | Zonula Occludens-A |

| ZO-B | Zonula Occludens-B |

References

- Lee, K.-W.; Lillehoj, H.-S.; Jang, S.-I.; Lee, S.-H.; Bautista, D.A.; Ritter, G.D.; Lillehoj, E.P.; Siragusa, G.R. Comparison of Live Eimeria Vaccination with In-Feed Salinomycin on Growth and Immune Status in Broiler Chickens. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 95, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, H.M.; McDougald, L.R. Raising Broiler Chickens without Ionophore Anticoccidials. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2023, 32, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, A.; Sohail, M.; Ahmad, A.; Shah, M.; Din, S.; Khan, I.; Shuiab, M.; Nasrullah; Shahzada, W.; Iqbal, M. Selected Herbal Plants Showing Enhanced Growth Performance, Ileal Digestibility, Bone Strength and Blood Metabolites in Broilers. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2020, 48, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabian, S.; Arabkhazaeli, F.; Seifouri, P.; Farahani, A. Morphometric Analysis of the Intestine in Experimental Coccidiosis in Broilers Treated with Anticoccidial Drugs. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2018, 13, 493–499. [Google Scholar]

- Calik, A.; Omara, I.I.; White, M.B.; Li, W.; Dalloul, R.A. Effects of Dietary Direct Fed Microbial Supplementation on Performance, Intestinal Morphology and Immune Response of Broiler Chickens Challenged With Coccidiosis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, Y.; Bai, X.; Zhang, R.; Lei, Y.; Wang, X. Effects of Eimeria Challenge on Growth Performance, Intestine Integrity, and Cecal Microbial Diversity and Composition of Yellow Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belote, B.L.; Soares, I.; Sanches, A.W.D.; de Souza, C.; Scott-Delaunay, R.; Lahaye, L.; Kogut, M.H.; Santin, E. Applying Different Morphometric Intestinal Mucosa Methods and the Correlation with Broilers Performance under Eimeria Challenge. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraieski, A.L.; Hayashi, R.M.; Sanches, A.; Almeida, G.C.; Santin, E. Effect of Aflatoxin Experimental Ingestion and Eimeira Vaccine Challenges on Intestinal Histopathology and Immune Cellular Dynamic of Broilers: Applying an Intestinal Health Index. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belote, B.L.; Soares, I.; Tujimoto-Silva, A.; Sanches, A.W.D.; Kraieski, A.L.; Santin, E. Applying I See inside Histological Methodology to Evaluate Gut Health in Broilers Challenged with Eimeria. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 276, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, P.P.d.A.B.M.; Paulino, P.G.; da Silva, N.M.; Galdino, K.C.P.; Rabello, C.A.; de Souza, F.G.; Reis, T.L.; Machado, L.d.S.; de Resende Souza, F.D.; Santos, H.A. Dose and Age-Dependent Effects of Eimeria spp. Infection on Cytokine and Intestinal Integrity Gene Expression in Broiler Chickens. Vet. Parasitol. 2025, 338, 110550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, P.-Y.; Yadav, S.; de Souza Castro, F.L.; Tompkins, Y.H.; Fuller, A.L.; Kim, W.K. Graded Eimeria Challenge Linearly Regulated Growth Performance, Dynamic Change of Gastrointestinal Permeability, Apparent Ileal Digestibility, Intestinal Morphology, and Tight Junctions of Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 4203–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lu, M.; Lillehoj, H.S. Coccidiosis: Recent Progress in Host Immunity and Alternatives to Antibiotic Strategies. Vaccines 2022, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Yu, Y.-H.; Hua, K.-F.; Chen, W.-J.; Zaborski, D.; Dybus, A.; Hsiao, F.S.-H.; Cheng, Y.-H. Management and Control of Coccidiosis in Poultry—A Review. Anim. Biosci. 2023, 37, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.L.; Kessler, A.M.; Penz Júnior, A.M.; Krabbe, E.L.; Brugalli, I.; Pophal, S. Evaluation of Monensin on the Performance and Carcass and Cuts Yield of Broilers. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2000, 29, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahininejad, H.; Rahimi, S.; Karimi Torshizi, M.A.; Arabkhazaeli, F.; Ayyari, M.; Behnamifar, A.; Abuali, M.; Grimes, J. Comparing the Effect of Phytobiotic, Coccidiostat, Toltrazuril, and Vaccine on the Prevention and Treatment of Coccidiosis in Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, H.D.; Jeffers, T.K.; Williams, R.B. Forty Years of Monensin for the Control of Coccidiosis in Poultry. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 1788–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Ward, T.; Southern, L.; Ingram, D. Interactive Effects of Sodium Bentonite and Coccidiosis with Monensin or Salinomycin in Chicks. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Pires, P.G.; Torres, P.; Teixeira Soratto, T.A.; Filho, V.B.; Hauptli, L.; Wagner, G.; Haese, D.; Pozzatti, C.D.; de Oliveira Moraes, P. Comparison of Functional-Oil Blend and Anticoccidial Antibiotics Effects on Performance and Microbiota of Broiler Chickens Challenged by Coccidiosis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Amine Benarbia, M.; Gaignon, P.; Manoli, C.; Chicoteau, P. Saponin-Rich Plant Premixture Supplementation Is as Efficient as Ionophore Monensin Supplementation Under Experimental Eimeria spp. Challenge in Broiler Chicken. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 946576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasuriya, S.S.; Park, I.; Lee, Y.; Richer, L.M.; Przybyszewski, C.; Gay, C.G.; van Oosterwijk, J.G.; Lillehoj, H.S. Effect of Orally Administered B. Subtilis-CNK-2 on Growth Performance, Immunity, Gut Health, and Gut Microbiome in Chickens Infected with Eimeria Acervulina and Its Potential as an Alternative to Antibiotics. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipper, M.; Andretta, I.; Lehnen, C.R.; Lovatto, P.A.; Monteiro, S.G. Meta-Analysis of the Performance Variation in Broilers Experimentally Challenged by Eimeria spp. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 196, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, G.C.; Esteves, G.F.; Volpato, F.A.; Miotto, R.; Mores, M.A.Z.; Ibelli, A.M.G.; Bastos, A.P. Effects of Varying Concentrations of Eimeria Challenge on the Intestinal Integrity of Broiler Chickens. Poultry 2024, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, P.-Y.; Choi, J.; Yadav, S.; Tompkins, Y.H.; Kim, W.K. Effects of Low-Crude Protein Diets Supplemented with Arginine, Glutamine, Threonine, and Methionine on Regulating Nutrient Absorption, Intestinal Health, and Growth Performance of Eimeria-Infected Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostagno, H.S.; Albino, L.F.T.; Hannas, M.I.; Donzele, J.L.; Sakomura, N.K.; Perazzo, F.G.; Saraiva, A.; Teixeira, M.L.; Rodrigues, P.B.; de Oliveira, R.F.; et al. Tabelas Brasileiras Para Aves e Suínos—Composição de Alimentos e Exigências Nutricionais, 4th ed.; Rostagno, H.S., Ed.; UFV: Viçosa, Brazil, 2017; ISBN 978-85-8179-120-3. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. AOAC Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Rockville, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, J.N. Coccidiosis: Oocyst Counting Technique for Coccidiostat Evaluation. Exp. Parasitol. 1970, 28, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, W.; Wurster, K. Alcian Blue Staining Intestinal Goblet Cell Antigen (GOA): A Marker for Gastric Signet Ring Cell and Colonic Colloidal Carcinoma. Klin. Wochenschr. 1978, 56, 1185–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisielinski, K.; Willis, S.; Prescher, A.; Klosterhalfen, B.; Schumpelick, V. A Simple New Method to Calculate Small Intestine Absorptive Surface in the Rat. Clin. Exp. Med. 2002, 2, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate Normalization of Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR Data by Geometric Averaging of Multiple Internal Control Genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, RESEARCH0034.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boever, S.; Vangestel, C.; De Backer, P.; Croubels, S.; Sys, S.U. Identification and Validation of Housekeeping Genes as Internal Control for Gene Expression in an Intravenous LPS Inflammation Model in Chickens. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 122, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, A.; Maier, H.J.; Fife, M.S. Selection of Reference Genes for Gene Expression Analysis by Real-Time QPCR in Avian Cells Infected with Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Avian Pathol. 2017, 46, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barekatain, R.; Chrystal, P.V.; Howarth, G.S.; McLaughlan, C.J.; Gilani, S.; Nattrass, G.S. Performance, Intestinal Permea-bility, and Gene Expression of Selected Tight Junction Proteins in Broiler Chickens Fed Reduced Protein Diets Supple-mented with Arginine, Glutamine, and Glycine Subjected to a Leaky Gut Model. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 6761–6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.F.; Chen, Y.P.; Chen, R.; Su, Y.; Zhang, R.Q.; He, Q.F.; Wang, K.; Wen, C.; Zhou, Y.M. Dietary Mannan Oligosaccharide Ameliorates Cyclic Heat Stress-Induced Damages on Intestinal Oxidative Status and Barrier Integrity of Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 4767–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelli, N.; Ramser, A.; Greene, E.S.; Beer, L.; Tabler, T.W.; Orlowski, S.K.; Pérez, J.F.; Solà-Oriol, D.; Anthony, N.B.; Dridi, S. Effects of Cyclic Chronic Heat Stress on the Expression of Nutrient Transporters in the Jejunum of Modern Broilers and Their Ancestor Wild Jungle Fowl. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Lan, R.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Li, H. Yupingfeng Polysaccharides Enhances Growth Performance in Qingyuan Partridge Chicken by Up-regulating the mRNA Expression of SGLT1, GLUT2 and GLUT5. Vet. Med. Sci. 2019, 5, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.K.; Singh, A.K.; Goo, D.; Choppa, V.S.R.; Ko, H.; Shi, H.; Kim, W.K. Graded Levels of Eimeria Infection Modulated Gut Physiology and Temporarily Ceased the Egg Production of Laying Hens at Peak Production. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.K.; Liu, G.; White, D.L.; Tompkins, Y.H.; Kim, W.K. Effects of Mixed Eimeria Challenge on Performance, Body Composition, Intestinal Health, and Expression of Nutrient Transporter Genes of Hy-Line W-36 Pullets (0–6 Wks of Age). Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubayashi, M.; Kinoshita, M.; Kobayashi, A.; Tsuchida, S.; Shibahara, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Nakamura, H.; Sasai, K.; Ushida, K. Parasitic Development in Intestines and Oocyst Shedding Patterns for Infection by Eimeria Uekii and Eimeria Raichoi in Japanese Rock Ptarmigans, Lagopus Muta Japonica, Protected by Cages in the Southern Japanese Alps. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2020, 12, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.P.; Guerin, M.T.; Hargis, B.M.; Page, G.; Barta, J.R. Monitoring Coccidia in Commercial Broiler Chicken Flocks in Ontario: Comparing Oocyst Cycling Patterns in Flocks Using Anticoccidial Medications or Live Vaccination. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.P.; Knox, J.; Dehaeck, B.; Huntington, B.; Rathinam, T.; Ravipati, V.; Ayoade, S.; Gilbert, W.; Adebambo, A.O.; Jatau, I.D. Re-Calculating the Cost of Coccidiosis in Chickens. Vet. Res. 2020, 51, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.R.; Silva, L.J.G.; Pereira, A.M.P.T.; Esteves, A.; Duarte, S.C.; Pena, A. Coccidiostats and Poultry: A Comprehensive Review and Current Legislation. Foods 2022, 11, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Osorio, S.; Chaparro-Gutiérrez, J.J.; Gómez-Osorio, L.M. Overview of Poultry Eimeria Life Cycle and Host-Parasite Interactions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Moraes, P.; da Silva Pires, P.G.; Benetti Filho, V.; Lima, A.L.F.; Kindlein, L.; Taschetto, D.; Favero, A.; Wagner, G. Intestinal Health of Broilers Challenged with Eimeria spp. Using Functional Oil Blends in Two Physical Forms with or without Anticoccidials. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, G. Effect of Probiotics on the Performance and Intestinal Health of Broiler Chickens Infected with Eimeria Tenella. Vaccines 2022, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangnumsawang, Y.; Zentek, J.; Goodarzi Boroojeni, F. Development and Functional Properties of Intestinal Mucus Layer in Poultry. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 745849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, F.L.S.; Teng, P.-Y.; Yadav, S.; Gould, R.L.; Craig, S.; Pazdro, R.; Kim, W.K. The Effects of L-Arginine Supplementation on Growth Performance and Intestinal Health of Broiler Chickens Challenged with Eimeria spp. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5844–5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Peebles, E.D.; Kiess, A.S.; Wamsley, K.G.S.; Zhai, W. Effects of Coccidial Vaccination and Dietary Antimicrobial Alternatives on the Growth Performance, Internal Organ Development, and Intestinal Morphology of Eimeria-Challenged Male Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 2054–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Lourenco, J.M.; Olukosi, O.A. Effects of Xylanase, Protease, and Xylo-Oligosaccharides on Growth Performance, Nutrient Utilization, Short Chain Fatty Acids, and Microbiota in Eimeria-Challenged Broiler Chickens Fed High Fiber Diet. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 15, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients | % |

|---|---|

| Corn | 57.36 |

| Soybean meal | 36.91 |

| Corn oil | 1.88 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.781 |

| Limestone | 0.787 |

| Salt | 0.456 |

| DL—Methionine | 0.322 |

| L—Lysine | 0.194 |

| L—Threonine | 0.085 |

| Choline chloride | 0.065 |

| Vitamin supplement 1 | 0.120 |

| Mineral supplement 2 | 0.050 |

| Total, kg | 100.00 |

| Calculated composition | |

| Dry matter,% | 88.86 |

| Organic matter,% | 85.70 |

| Crude protein,% | 22.60 |

| Metabolizable energy, kcal/kg | 3000 |

| Ethereal extract,% | 5.25 |

| Arginine | 1.287 |

| Lysine | 1.217 |

| Methionine | 0.615 |

| Methionine + Cysteine | 0.905 |

| Threonine | 0.770 |

| Tryptophan | 0.239 |

| Valine | 0.870 |

| Variables | Treatments | SEM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN | CC | MON | |||

| 0 to 7 days | |||||

| BWG, g | 147 | 149 | 153 | 1.863 | 0.616 |

| FI, g | 146 | 150 | 160 | 2.547 | 0.078 |

| FCR | 0.992 | 1.006 | 1.047 | 0.012 | 0.136 |

| BW, g | 185 | 187 | 191 | 1.843 | 0.352 |

| 0 to 14 days | |||||

| BWG, g | 490 ab | 474 b | 526 a | 8.143 | <0.001 |

| FI, g | 632 | 618 | 662 | 9.204 | 0.123 |

| FCR | 1.291 | 1.306 | 1.259 | 0.013 | 0.314 |

| BW, g | 528 ab | 512 b | 564 a | 8.128 | 0.024 |

| 0 to 21 days | |||||

| BWG, g | 1017 a | 767 c | 866 b | 25.995 | <0.001 |

| FI, g | 1225 a | 1021 c | 1101 b | 22.830 | <0.001 |

| FCR | 1.205 a | 1.333 b | 1.273 ab | 0.018 | 0.010 |

| BW, g | 1073 a | 839 b | 896 b | 26.010 | <0.001 |

| 0 to 28 days | |||||

| BWG, g | 1818 a | 1484 c | 1590 b | 36.237 | <0.001 |

| FI, g | 2312 a | 2016 b | 2102 b | 35.957 | <0.001 |

| FCR | 1.275 a | 1.359 b | 1.322 b | 0.010 | <0.001 |

| BW, g | 1856 a | 1522 c | 1628 b | 36.249 | <0.001 |

| Parameters | Treatment | SEM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM | CC | MON | |||

| ATTD | |||||

| DM, % | 71.58 a | 62.87 b | 70.06 a | 1.093 | <0.001 |

| OM, % | 75.97 a | 68.63 b | 74.69 a | 0.931 | <0.001 |

| Ash, % | 46.11 a | 32.35 b | 43.02 a | 1.653 | <0.001 |

| CP, % | 69.02 a | 59.85 b | 66.48 a | 1.136 | <0.001 |

| GE, % | 77.57 a | 70.11 b | 76.44 a | 0.962 | <0.001 |

| AME, kcal | 3896 a | 3521 b | 3839 a | 48.33 | <0.001 |

| AMEn, kcal | 3654 a | 3312 b | 3606 a | 44.55 | 0.001 |

| Parameters | Treatment | SEM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN | CC | MON | |||

| Duodenum | |||||

| Villus height, μm | 904 b | 1035 ab | 1077 a | 28.47 | 0.017 |

| Villus width, μm | 213 | 205 | 218 | 6.81 | 0.697 |

| Crypt depth, μm | 111 b | 160 a | 165 a | 7.62 | 0.001 |

| Crypt width, μm | 79.6 | 78.5 | 75.7 | 1.71 | 0.470 |

| Vh:Cd | 8.25 | 6.63 | 6.59 | 0.328 | 0.066 |

| Absorptive surface, μm2 | 9.54 | 11.16 | 11.35 | 0.368 | 0.065 |

| Jejunum | |||||

| Villus height, μm | 682 a | 522 b | 582 ab | 22.59 | 0.016 |

| Villus width, μm | 192 | 214 | 216 | 5.983 | 0.261 |

| Crypt depth, μm | 112 b | 153 a | 154 a | 6.602 | 0.013 |

| Crypt width, μm | 77.41 | 82.84 | 83.51 | 2.381 | 0.587 |

| Vh:Cd | 6.14 a | 3.45 b | 3.84 b | 0.316 | <0.01 |

| Absorptive surface, μm2 | 7.72 a | 5.65 b | 6.11 b | 0.279 | 0.002 |

| Parameters | Treatment | SEM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN | CC | MON | |||

| Duodenum | |||||

| Lamina propria thickness | 1.22 b | 2.05 a | 1.98 a | 0.121 | 0.001 |

| Epithelial thickness | 1.13 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 0.051 | 0.404 |

| Enterocytes’ proliferation | 1.03 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.053 | 0.056 |

| Inflammatory cell infiltration in the epithelium | 0.53 b | 0.77 a | 0.79 a | 0.057 | 0.009 |

| Inflammatory cell infiltration in the lamina propria | 1.22 b | 2.10 a | 2.02 a | 0.128 | <0.001 |

| Goblet cells’ proliferation | 1.90 a | 1.33 b | 1.12 b | 0.140 | 0.007 |

| Congestion | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.074 | 0.915 |

| Presence of oocysts | 0.00 c | 1.50 b | 5.01 a | 0.609 | <0.001 |

| Total | 7.35 b | 9.98 ab | 13.28 a | 0.825 | 0.004 |

| Jejunum | |||||

| Lamina propria thickness | 1.23 b | 2.32 a | 2.04 a | 0.136 | <0.001 |

| Epithelial thickness | 1.08 a | 0.88 b | 0.93 ab | 0.029 | 0.012 |

| Enterocytes’ proliferation | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.025 | 0.507 |

| Inflammatory cell infiltration in the epithelium | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.054 | 0.909 |

| Inflammatory cell infiltration in the lamina propria | 1.25 b | 2.12 a | 1.90 a | 0.118 | 0.003 |

| Goblet cells’ proliferation | 2.02 a | 0.35 c | 0.82 b | 0.184 | <0.001 |

| Congestion | 0.37 | 1.12 | 0.54 | 0.134 | 0.092 |

| Presence of oocysts | 0.00 b | 4.53 a | 5.73 a | 0.640 | <0.001 |

| Total | 7.43 b | 12.70 a | 13.47 a | 0.755 | <0.001 |

| Cecum | |||||

| Enterocytes’ proliferation | 0.43 b | 0.40 b | 0.92 a | 0.072 | 0.006 |

| Inflammatory cell infiltration in the epithelium | 0.03 b | 0.47 a | 0.32 a | 0.056 | 0.004 |

| Inflammatory cell infiltration in the lamina propria | 1.80 b | 2.70 a | 2.64 a | 0.129 | 0.003 |

| Congestion | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 0.098 | 0.081 |

| Presence of oocysts | 0.00 b | 8.85 a | 6.78 a | 1.059 | <0.001 |

| Total | 2.37 b | 12.92 a | 11.34 a | 1.273 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

de Lima, P.P.d.A.B.M.; Barbosa, J.A.d.L.; Vieira, G.C.; de Castro Campos Pereira, J.; Menegalle, M.T.; Santos, H.A.; Silveira, R.M.F.; Dilelis, F. Effects of Eimeria Challenge and Monensin Supplementation on Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, and Intestinal Health of Broilers. Poultry 2026, 5, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010012

de Lima PPdABM, Barbosa JAdL, Vieira GC, de Castro Campos Pereira J, Menegalle MT, Santos HA, Silveira RMF, Dilelis F. Effects of Eimeria Challenge and Monensin Supplementation on Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, and Intestinal Health of Broilers. Poultry. 2026; 5(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010012

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Lima, Pamella Pryscila de Alvarenga Bissoli Maciel, José Andrew de Lira Barbosa, Giulia Cancian Vieira, Júlia de Castro Campos Pereira, Mateus Tinelli Menegalle, Huarrisson Azevedo Santos, Robson Mateus Freitas Silveira, and Felipe Dilelis. 2026. "Effects of Eimeria Challenge and Monensin Supplementation on Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, and Intestinal Health of Broilers" Poultry 5, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010012

APA Stylede Lima, P. P. d. A. B. M., Barbosa, J. A. d. L., Vieira, G. C., de Castro Campos Pereira, J., Menegalle, M. T., Santos, H. A., Silveira, R. M. F., & Dilelis, F. (2026). Effects of Eimeria Challenge and Monensin Supplementation on Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, and Intestinal Health of Broilers. Poultry, 5(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010012