Determination of the Requirements of Standardized Ileal Digestible Methionine Plus Cysteine and Lysine in Male Chicks of a Layer Breed (LSL Classic) During the Starter Period (1–21 d)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

2.2. Housing and Management

2.3. Diets

2.4. Chemical Analysis of Diets

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

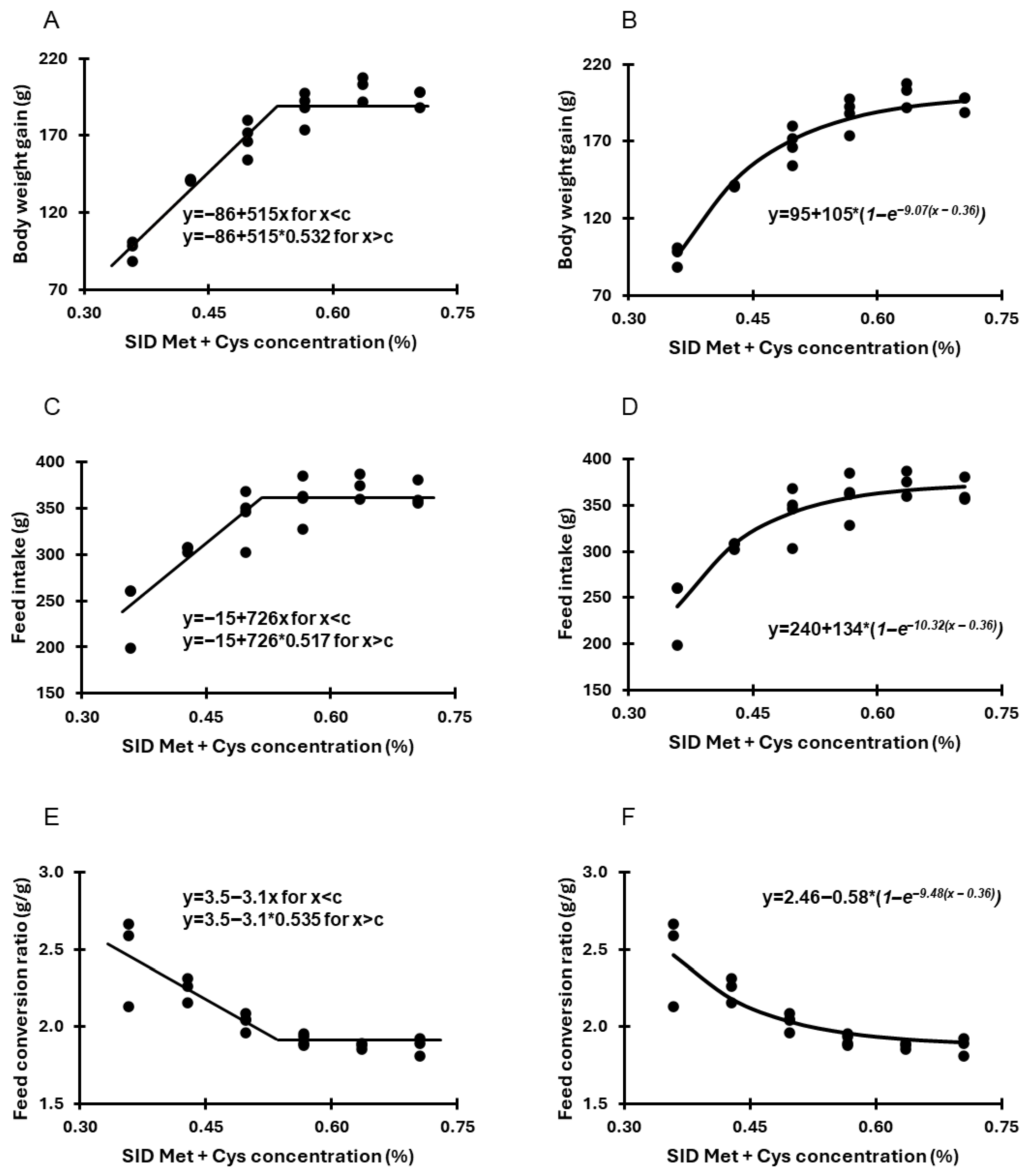

3.1. Trial 1—Determination of SID Met + Cys Requirement

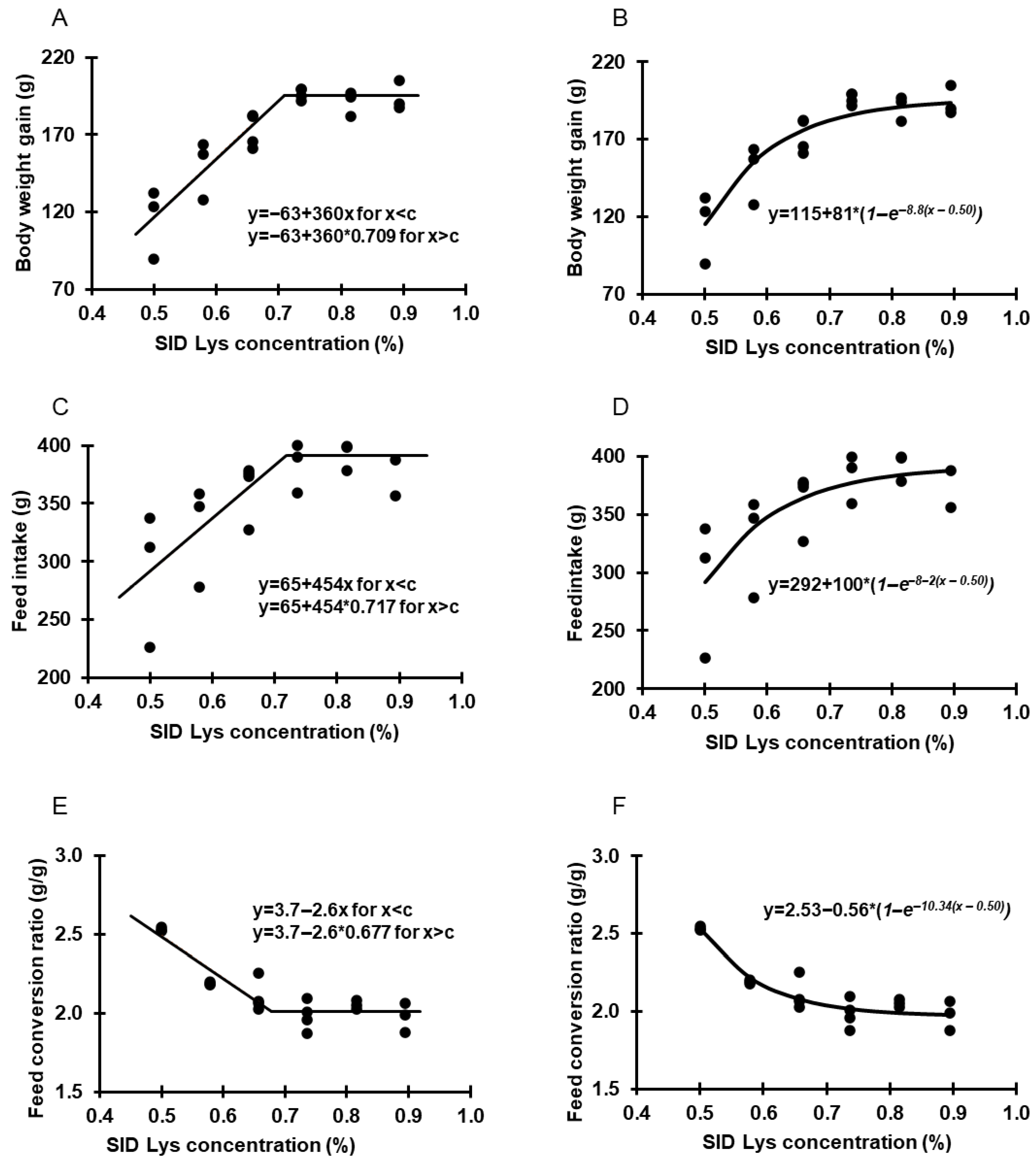

3.2. Trial 2—Determination of SID Lys Requirement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMEN | Apparent metabolizable energy, nitrogen-corrected |

| CP | Crude protein |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| DM | Dry matter |

| EE | Ether extract |

| IU | International Units |

| Lys | Lysine |

| Met | Methionine |

| MJ | Megajoule |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SID | Standardized ileal digestible |

References

- Krautwald-Junghanns, M.E.; Cramer, K.; Fischer, B.; Förster, A.; Galli, R.; Kremer, F.; Mapesa, E.U.; Meissner, S.; Preisinger, R.; Preusse, G.; et al. Current approaches to avoid the culling of day-old male chicks in the layer industry, with special reference to spectroscopic methods. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giersberg, M.F.; Kemper, N. Rearing male layer chickens: A German perspective. Agriculture 2018, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damme, K.; Ristic, R. Fattening performance, meat yield and economic aspects of meat and layer type hybrids. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2003, 59, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Aviagen. ROSS 308 ROSS 308 FF. Performance Objectives. 2022. Available online: https://aviagen.com/assets/Tech_Center/Ross_Broiler/RossxRoss308-BroilerPerformanceObjectives2022-EN.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Cobb. Cobb500 Broiler Performance & Nutrition Supplement. 2022. Available online: https://www.cobbgenetics.com/assets/Cobb-Files/2022-Cobb500-Broiler-Performance-Nutrition-Supplement.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Buhl, A.C. Legal aspects of prohibiting chick shredding in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Glob. J. Anim. Law 2013, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bruijns, M.R.N.; Blok, V.; Stassen, E.N.; Gremmen, H.G.J. Moral “lock in” in responsible innovation: The ethical and social aspects of killing day-old chicks and its alternatives. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2015, 28, 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, E.N.; Oliemans, E.; van Gerwen, M.A.A.M. The need for an alternative to culling day-old male layer chicks: A survey on awareness, alternatives, and the willingness to pay for alternatives in a selected population of dutch citizens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 662197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierschutzgesetz. Section 4c of the Animal Protection Act, as Promulgated on 18 May 2006 (Federal Law Gazette I pp. 1206, 1313), Last Amended by Article 2 Paragraph 20 of the Act of 20 December 2022 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 2752). Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tierschg/BJNR012770972.html (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Corion, M.; Santos, S.; De Ketelaere, B.; Spasic, D.; Hertog, M.; Lammertyn, J. Trends in in ovo sexing technologies: Insights and interpretation from papers and patents. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Li, B.; Zhu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, W. A review of key techniques for in ovo sexing of chicken eggs. Agriculture 2023, 13, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süß, S.C.; Werner, J.; Saller, A.M.; Weiss, L.; Reiser, J.; Ondracek, J.M.; Zablotski, Y.; Kollmannsperger, S.; Anders, M.; Potschka, H.; et al. Nociception in chicken embryos, Part III: Analysis of movements before and after application of a noxious stimulus. Animals 2023, 13, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landwirtschaft.de. Was Ist Seit Dem Verbot Vom Kükentöten Passiert? Available online: https://www.landwirtschaft.de/tier-und-pflanze/tier/gefluegel/was-ist-seit-dem-verbot-vom-kuekentoeten-passiert (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Ammer, S.; Qunander, N.; Posch, J.; Maurer, V.; Leiber, F.L. Fattening performance of male layer hybrids fed different protein sources. Agrar. Schweiz 2017, 8, 120–125. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Son, J.; Lee, W.-D.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, H.; Hong, E.-C.; Kim, H.-J. Effect of dietary crude protein reduction levels on performance, nutrient digestibility, nitrogen utilization, blood parameters, meat quality, and welfare index of broilers in welfare-friendly environments. Animals 2024, 14, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rauglaudre, T.; Méda, B.; Fontaine, S.; Lambert, W.; Fournel, S.; Létourneau-Montminy, M.-P. Meta-analysis of the effect of low-protein diets on the growth performance, nitrogen excretion, and fat deposition in broilers. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1214076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmert, J.L.; Baker, D.H. Use of the ideal protein concept for precision formulation of amino acid levels in broiler diets. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1997, 6, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macelline, S.P.; Toghyani, M.; Chrystal, P.V.; Selle, P.H.; Liu, S.Y. Amino acid requirements for laying hens: A comprehensive review. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann. Lohmann LSL-Classic Layers. Management Guide Cage Housing. 2020. Available online: https://lohmann-breeders.com/media/strains/cage/management/LOHMANN-LSL-Classic-Cage.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Evonik. AminoDat®, version 5.0.; Evonik Nutrition and Care GmbH, Animal Nutrition: Hanau, Germany, 2016.

- VDLUFA (Verband Deutscher Landwirtschaftlicher Untersuchungs- und Forschungsanstalten). Die Chemische Untersuchung von Futtermitteln. VDLUFA-Methodenbuch. Band III; Ergänzungslieferungen von 1983, 1988, 1992, 1997, 2004, 2006, 2007; VDLUFA-Verlag: Darmstadt, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International (Association of Official Analytical Chemists). Official Methods of Analysis, 16th ed.; Association of Analytical Communities: Arlington, VA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitz, J.O.; Fleischmann, A.; Ehbrecht, T.; Most, E.; Friedrichs, S.; Whelan, R.; Gessner, D.K.; Failing, K.; Lütjohann, D.; Eder, K. Effects of supplementation of DL-methionine on tissue and plasma antioxidant status during heat-induced oxidative stress in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 6837–6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WPSA (World’s Poultry Science Association). The prediction of apparent metabolizable energy values for poultry in compound feeds. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 1984, 40, 181–182. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, C.; Morris, T.R.; Jennings, J.R. A model for the description and prediction of the response of laying hens to amino acid intake. Br. Poult. Sci. 1973, 14, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, M.F.; Garthwaite, P. The form of response of body protein accretion to dietary amino acid supply. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.E.; van Lingen, H.J.; da Silva-Pires, P.G.; Batanon-Alavo, D.I.; Rouffineau, F.; Kebreab, E. Evaluating growth response of broiler chickens fed diets supplemented with synthetic DL-methionine or DL-hydroxy methionine: A meta-analysis. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, L.G.; Sakomura, N.K.; Suzuki, R.M.; Dorigam, J.C.P.; Viana, G.S.; Van Milgen, J.; Denadai, J.C. Methionine to cysteine ratio in the total sulfur amino acid requirements and sulfur amino acid metabolism using labelled amino acid approach for broilers. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.H.; Fernandez, S.R.; Webel, D.M.; Parsons, C.M. Sulfur amino acid requirement and cystine replacement value of broiler chicks during the period three to six weeks posthatching. Poult. Sci. 1996, 75, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviagen. Ross—Nutrition Specifications: All Plant Protein-Based Feeds. 2022. Available online: https://aviagen.com/assets/Tech_Center/Ross_Broiler/Ross-PlantProteinBasedBroilerNutritionSpecifications2022-EN.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Chamruspollert, M.; Pesti, G.M.; Bakalli, R.I. Determination of the methionine requirement of male and female broiler chicks using an indirect amino acid oxidation method. Poult. Sci. 2002, 81, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyantini, N.G.A.; Ulrikus, R.I.; Bryden, W.I.; Li, X. Different levels of digestible methionine on performance of broiler starter. Anim. Prod. 2010, 12, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Leeson, S.; Caston, L.; Summers, J.D. Broiler response to diet energy. Poult. Sci. 1996, 75, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, F.X.; Gruber, K.; Kirchgessner, M. The ideal dietary amino acid pattern for broiler-chicks of age 7 to 28 days. Eur. Poult. Sci. 2001, 65, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Dietary requirements of synthesizable amino acids by animals: A paradigm shift in protein nutrition. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.H.; Han, Y. Ideal amino acid profile for chicks during the first three weeks posthatching. Poult. Sci. 1996, 73, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelaere, L.; Le Cour Grandmaison, J.; Martin, N.; Lambert, W. Amino acid supplementation to reduce environmental impacts of broiler and pig production: A review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 689259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, H.M.; Patterson, P.H.; Ricke, S.C.; Kim, W.K. Enhancement of microbial nitrification to reduce ammonia emission from poultry manure: A review. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2014, 70, 839–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Stevenson, D.S.; Uwizeye, A.; Tempio, G.; Sutton, M.A. A climate-dependent global model of ammonia emissions from chicken farming. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Chiesa, T.; Archontoulis, S.V.; Emmett, B.D.; Northrup, D.; Miguez, F.E.; Baum, M.E.; Venterea, R.T.; Malone, R.W.; Necpalova, M.; Iqbal, J.; et al. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from North American soybean production. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K.R.G.; Ventura, M.U.; Barizon, R.R.M.; Folegatti-Matsuura, M.I.S.; Ralisch, R.; Mrtvi, P.R.; Possamai, E.J. Environmental performance of phytosanitary control techniques on soybean crop estimated by life cycle assessment (LCA). Environ. Sci. Poll. 2023, 30, 58315–58329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucić, R.; Raposo, M.; Chervinska, A.; Domingos, T.; Teixeira, R.F.M. Global greenhouse gas emissions and land use impacts of soybean production: Systematic review and analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wimer, F.R.; Zhou, M.; Pinheiro, M.J.; Fernández, P.D. Socio-ecological impacts and sustainable transformation pathways of soybean cultivation in the Brazilian Amazon region. Land 2025, 14, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, N.P.; Urriola, P.E.; Pelton, R.E.O.; Dhar, A.R.; Schmitt, J.; Shurson, G.C. Explaining global variation in life-cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from soybeans and soybean meal: A systematic review. Agric. Syst. 2026, 233, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Emous, R.A.; Winkel, A.; Aarnink, A.J.A. Effects of dietary crude protein levels on ammonia emission, litter and manure composition, N losses, and water intake in broiler breeders. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 6618–6625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cour Grandmaison, J.; Martin, N.; Lambert, W.; Corrent, E. Benefits of low dietary crude protein strategies on feed global warming potential in broiler and pig production systems: A case study. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Life Cycle Assessment of Food, Berlin, Germany, 13–16 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, M.; Pesti, G.M. Comparison of ingredient usage and formula costs in poultry feeds using different amino acid digestibility databases. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2012, 21, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahi, A.; Shir, M.H.; Attia, Y.A.; Fahmy, K.N.E.; Bovera, F.; Tufarelli, V. Impact of low-protein diets on broiler nutrition, production sustainability, gene expression, meat quality and greenhouse gas emissions. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2025, 53, 2473419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, M.; Hahn, G.; Damme, K.; Schmutz, M. Utilization of laying-type cockerels as “Coquelets”: Influence of genotype and diet characteristics on growth performance and carcass composition. Eur. Poult. Sci. 2012, 76, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, M.; Müller, S.; Mazzolini, L.; Messikommer, R.E.; Gangnat, I.D.M. Are dual-purpose and male layer chickens more resilient against a low-protein–low-soybean diet than slow-growing broilers? Br. Poult. Sci. 2020, 61, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbo, N.B.; Salces, A.J.; Oliveros, M.C.R.; Alberto, J.; Nuez, I.; Albajadelo, H.M.; Dominguez, J.M.D. Utilization of male layer chickens (Bovans White and ISA Brown) for meat production under free ranged systems. Philipp. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2022, 48, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

| Component (g/kg) | Trial 1 | Trial 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Faba bean | 200 | - |

| Wheat | 70 | 633 |

| Soybean meal | 120 | 122 |

| Wheat bran | - | 80 |

| Corn | 513 | 55 |

| Corn gluten | - | 20 |

| Mineral and vitamin mixture 1 | 20 | 20 |

| Soybean oil | 33 | 17 |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 12 | 16 |

| Calcium carbonate | 11 | 16 |

| Sodium chloride | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| L-Valine | 2.5 | 4.0 |

| L-Isoleucine | 2.5 | 4.0 |

| L-Threonine | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| L-Arginine | 1.3 | 2.7 |

| DL-Methionine | - | 2.5 |

| L-Lysine HCL | 3.5 | - |

| L-Tryptophan | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Nutrients (analysed) | ||

| Dry matter (DM, %) | 87.70 | 86.60 |

| Crude protein (% of DM) | 17.96 | 18.71 |

| Ether extract (% of DM) | 6.06 | 4.14 |

| Crude ash (% of DM) | 6.42 | 7.53 |

| Crude fiber (% of DM) | 4.14 | 3.82 |

| Starch (% of DM) | 52.33 | 50.27 |

| Sugar (% of DM) | 2.88 | 3.44 |

| Calcium (% of DM) | 1.19 | 1.45 |

| Phosphorus (% of DM) | 0.95 | 1.08 |

| AMEN (MJ/kg DM, calculated) | 13.97 | 13.16 |

| Amino acids (g/kg diet) | ||

| Arginine | 10.98 | 10.46 |

| Cysteine | 3.02 | 3.57 |

| Histidine | 3.50 | 3.17 |

| Isoleucine | 7.08 | 8.19 |

| Leucine | 12.41 | 11.59 |

| Lysine | 10.08 | 5.68 |

| Methionine | 1.49 | 4.68 |

| Phenylalanine | 6.30 | 6.52 |

| Threonine | 7.56 | 8.34 |

| Valine | 7.59 | 8.81 |

| SID amino acids (g/kg diet) 2 | ||

| Arginine | 10.43 | 9.75 |

| Cysteine | 2.06 | 2.52 |

| Histidine | 2.77 | 2.57 |

| Isoleucine | 6.66 | 8.14 |

| Leucine | 10.32 | 10.17 |

| Lysine | 10.02 | 5.02 |

| Methionine | 1.53 | 4.46 |

| Phenylalanine | 5.22 | 5.89 |

| Threonine | 6.72 | 7.63 |

| Valine | 6.94 | 8.62 |

| Met + Cys (%), Trial 1 | Lys (%), Trial 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Total * | SID ** | Total * | SID ** |

| 1 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.50 |

| 2 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.65 | 0.58 |

| 3 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 0.66 |

| 4 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.81 | 0.74 |

| 5 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.89 | 0.82 |

| 6 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.97 | 0.89 |

| SID Met + Cys (%) | Body Weight, d 1 (g) | Body Weight, d 21 (g) | Body Weight Gain (d1–d21, g) | Feed Intake (d1–d21, g) | FCR (g Feed:g Gain) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.36 | 35.0 ± 0.2 | 131 ± 6 d | 96 ± 6 d | 240 ± 36 b | 2.50 ± 0.22 b |

| 0.43 | 35.5 ± 0.9 | 176 ± 0 c | 141 ± 1 c | 306 ± 3 a | 2.17 ± 0.03 a |

| 0.50 | 35.2 ± 0.9 | 203 ± 11 b | 168 ± 11 b | 342 ± 28 a | 2.03 ± 0.05 a |

| 0.57 | 35.0 ± 0.9 | 223 ± 10 a | 188 ± 10 a | 360 ± 24 a | 1.91 ± 0.03 a |

| 0.64 | 35.3 ± 1.1 | 236 ± 8 a | 201 ± 8 a | 374 ± 14 a | 1.89 ± 0.02 a |

| 0.71 | 35.2 ± 1.3 | 230 ± 7 a | 195 ± 6 a | 365 ± 14 a | 1.88 ± 0.06 a |

| p-value | 0.98 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Broken-Line | Exponential |

| Body weight gain | ||

| Optimum (g) | 188 | 190 |

| SID Met + Cys (%) | 0.53 | 0.62 |

| Fit (R2) | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.016 |

| Feed intake | ||

| Optimum (g) | 360 | 355 |

| SID Met + Cys (%) | 0.52 | 0.55 |

| Fit (R2) | 0.62 | 0.77 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.022 |

| Feed conversion ratio | ||

| Optimum (g feed/g gain) | 1.92 | 1.99 |

| SID Met + Cys (%) | 0.53 | 0.53 |

| Fit (R2) | 0.69 | 0.88 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.005 |

| SID Lys (%) | Body Weight, d 1 (g) | Body Weight, d 21 (g) | Body Weight Gain (d1–d21, g) | Feed Intake (d1–d21, g) | FCR (g Feed:g Gain) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.50 | 36.8 ± 0.0 | 152 ± 23 b | 115 ± 23 b | 292 ± 58 b | 2.53 ± 0.01 c |

| 0.58 | 36.7 ± 0.3 | 186 ± 19 b | 150 ± 19 b | 328 ± 43 a | 2.19 ± 0.01 b |

| 0.66 | 36.8 ± 0.2 | 210 ± 11 a | 173 ± 11 a | 364 ± 24 a | 2.11 ± 0.10 a |

| 0.74 | 36.8 ± 0.1 | 233 ± 4 a | 196 ± 4 a | 389 ± 21 a | 1.98 ± 0.09 a |

| 0.82 | 36.9 ± 0.1 | 228 ± 8 a | 191 ± 8 a | 392 ± 12 a | 2.05 ± 0.03 a |

| 0.89 | 37.1 ± 0.4 | 231 ± 9 a | 194 ± 9 a | 384 ± 24 a | 1.98 ± 0.10 a |

| p-value | 0.42 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Broken-Line | Exponential |

| Body weight gain | ||

| Optimum (g) | 193 | 186 |

| SID Lys (%) | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| Fit (R2) | 0.70 | 0.79 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.02 |

| Feed intake | ||

| Optimum (g) | 391 | 372 |

| SID Lys (%) | 0.72 | 0.70 |

| Fit (R2) | 0.20 | 0.47 |

| p-value | 0.046 | <0.001 |

| Feed conversion ratio | ||

| Optimum (g feed/g gain) | 2.02 | 2.08 |

| SID Lys (%) | 0.68 | 0.66 |

| Fit (R2) | 0.64 | 0.75 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Schemmann, K.; Geßner, D.K.; Most, E.; Eder, K. Determination of the Requirements of Standardized Ileal Digestible Methionine Plus Cysteine and Lysine in Male Chicks of a Layer Breed (LSL Classic) During the Starter Period (1–21 d). Poultry 2026, 5, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010011

Schemmann K, Geßner DK, Most E, Eder K. Determination of the Requirements of Standardized Ileal Digestible Methionine Plus Cysteine and Lysine in Male Chicks of a Layer Breed (LSL Classic) During the Starter Period (1–21 d). Poultry. 2026; 5(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchemmann, Karen, Denise K. Geßner, Erika Most, and Klaus Eder. 2026. "Determination of the Requirements of Standardized Ileal Digestible Methionine Plus Cysteine and Lysine in Male Chicks of a Layer Breed (LSL Classic) During the Starter Period (1–21 d)" Poultry 5, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010011

APA StyleSchemmann, K., Geßner, D. K., Most, E., & Eder, K. (2026). Determination of the Requirements of Standardized Ileal Digestible Methionine Plus Cysteine and Lysine in Male Chicks of a Layer Breed (LSL Classic) During the Starter Period (1–21 d). Poultry, 5(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry5010011