Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Resistance Genes of Enterococci from Broiler Chicken Litter

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Sampling Method, Bacterial Isolation and Growth Condition

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assays

2.3. Enterococci Speciation

2.4. Detection and Identification of Resistance Genes

2.5. Insertion Sequence Detection

2.6. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

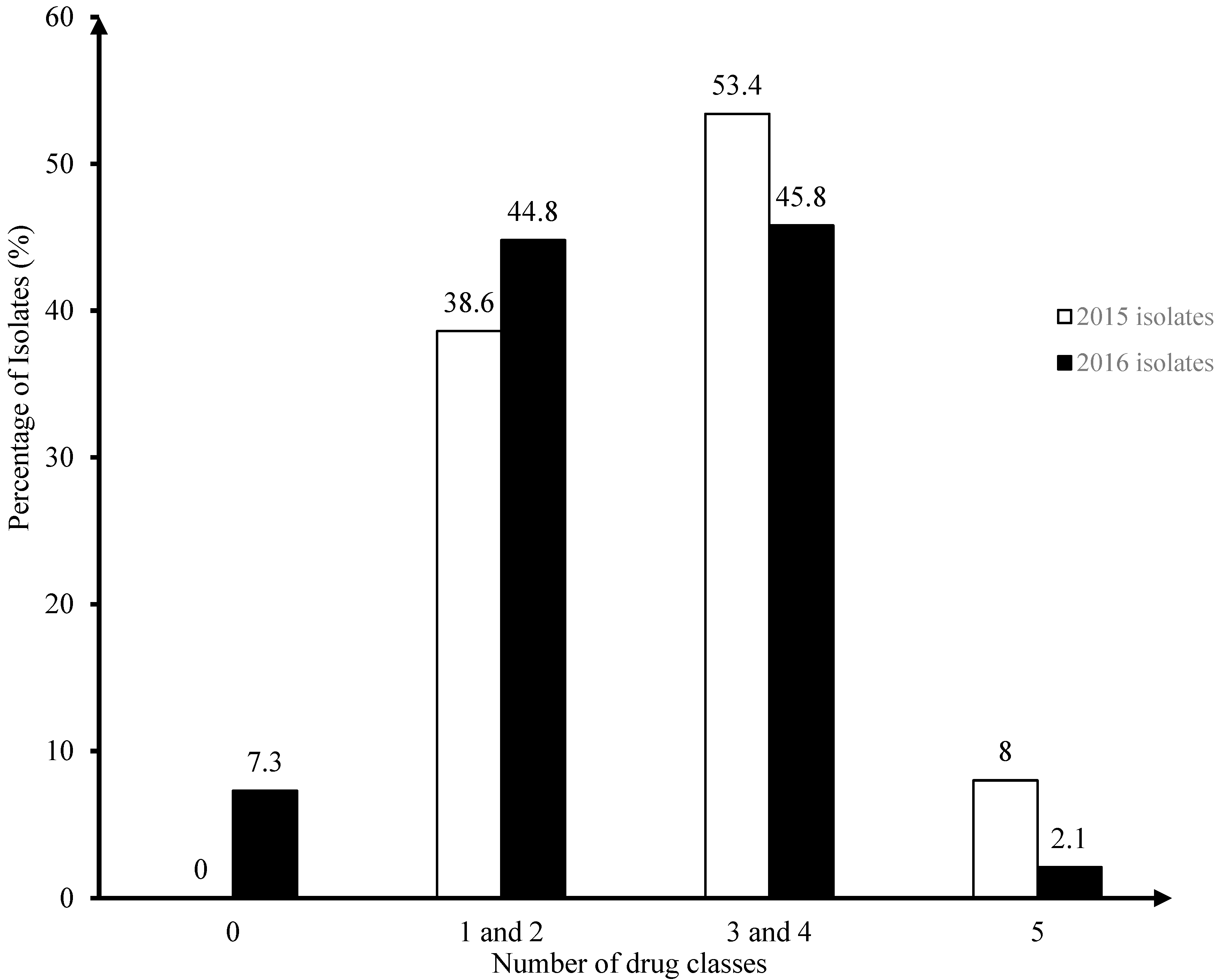

3.1. Surveillance of AMR in Enterococci Isolates from Broiler Chicken Farms in 2015–2016 (Figure 1)

3.2. Speciation of Enterococcus Isolates from Broiler Chicken Farms (Table 2)

| Enterococcus Species | 2015 | 2016 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Isolates | Percentage | Number of MDR Isolates | Percentage | Number of Isolates | Percentage | Number of MDR Isolates | Percentage | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 52 | 59% | 37 | 42.04% | 57 | 59% | 29 | 30% |

| Enterococcus faecium | 35 | 40% | 17 | 19.32% | 37 | 39% | 16 | 17% |

| Enterococcus durans | 1 | 1% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Enterococcus hirae | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2% | 1 | 1% |

| Total | 88 | 100% | 54 | 61.36% | 96 | 100% | 46 | 48% |

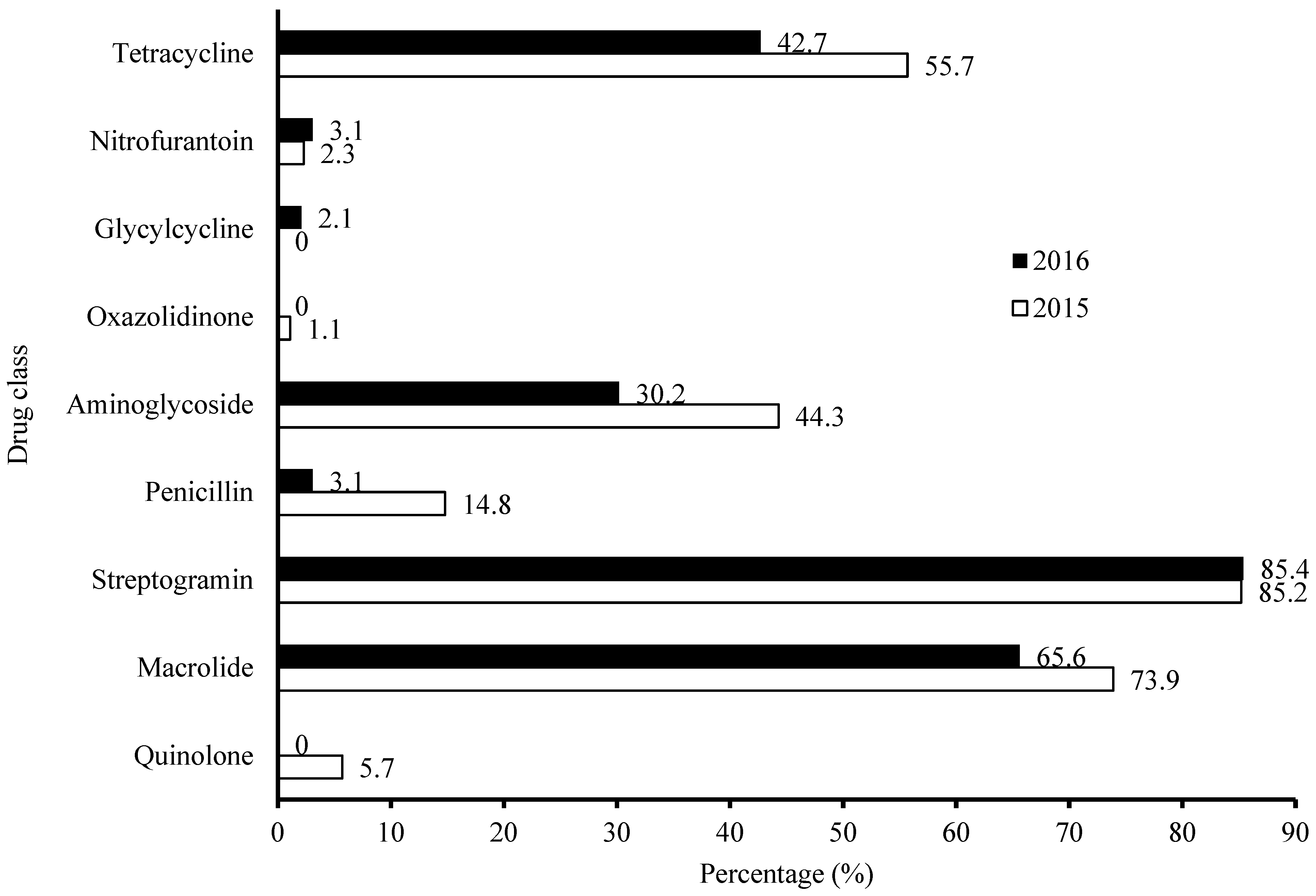

3.3. Characterization of Overall AMR Profile—Frequency Distribution per Antimicrobial Agents in Year 2015–2016 Categorized by Drug Classes (Figure 2)

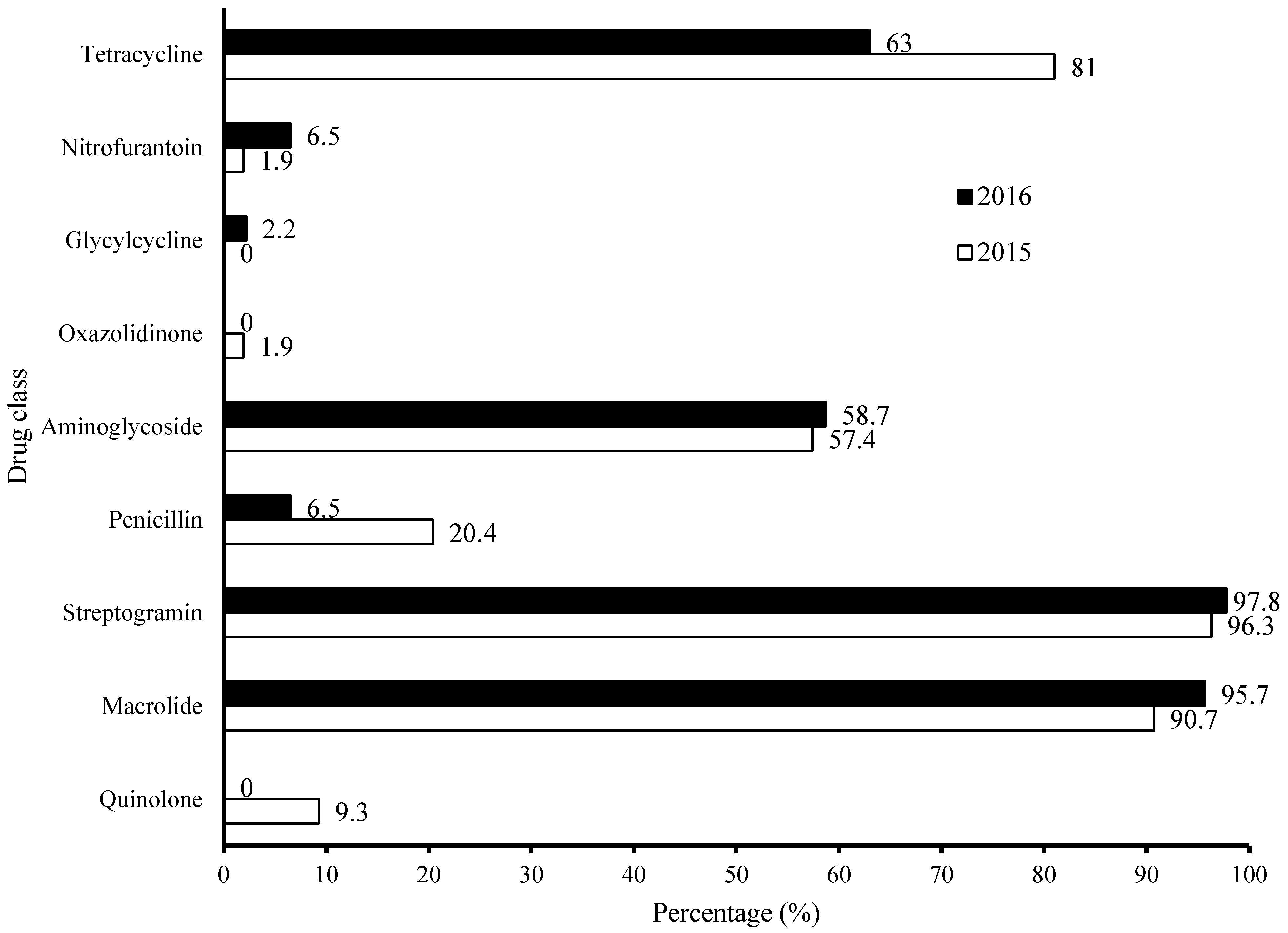

3.4. Characterization of AMR Profile—Frequency Distribution per Antimicrobial Agents in MDR Community in Year 2015–2016 Categorized by Drug Classes (Figure 3)

3.5. Characterization of AMR Patterns of Isolates Resistant to a Combination of Three or More Antimicrobials

3.6. Characterization of AMR Patterns of Isolates with Intermediate Resistance in Combinations of Three or More Antimicrobials (Table 4)

| Pattern | 2015 | 2016 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis | E. faecium | E. faecalis | E. faecium | ||

| dox-ery-lzd | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| dox-ery-van | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| dox-lvx_qd | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| dox-lvx-qd-str | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| dox-lvx-str | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| ery-lvx-lzd-tgc | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ery-str-van | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| lvx-lzd-str-tgc-van | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| lvx-lzd-van | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| lvx-nit-van | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| lvx-str-van | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Pattern | 2015 | 2016 | Total | ||

| DOX-ERY-lvx-QD | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

| DOX-ERY-lvx-QD-STR | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

| DOX-ery-QD | 0 | 6 | 0 | ||

| ERY-QD-str | 0 | 5 | 5 | ||

| dox-ERY-QD | 0 | 6 | 6 | ||

| dox-ERY-lvx-QD-str | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

3.7. The Association of Phenotype and Genotype in MDR Isolates 2015–2016

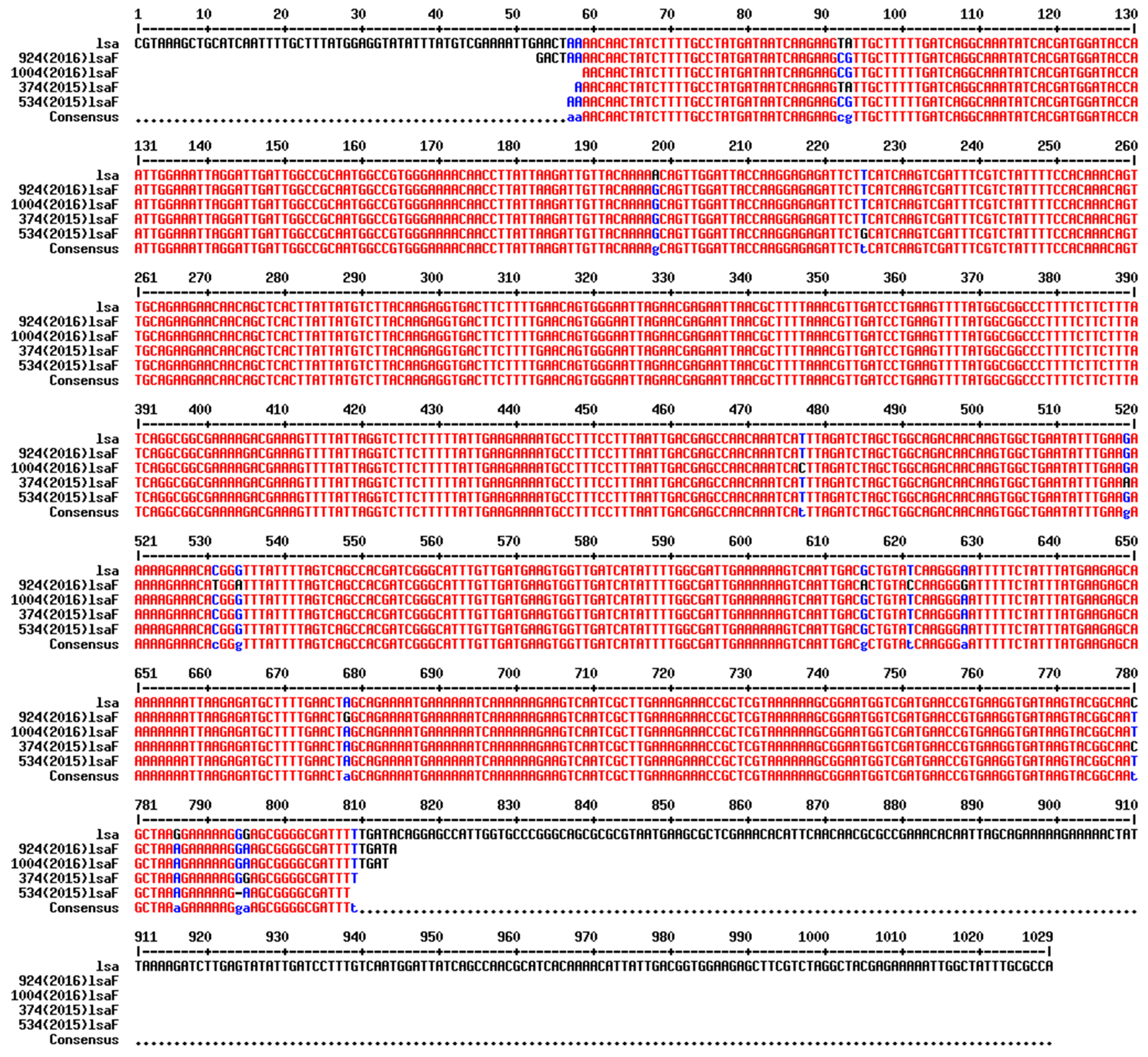

3.8. Insertion Sequence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, H.-S.C. Overview of the World Broiler Industry: Implications for the Philippines. Asian J. Agric. Dev. 2007, 4, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, J.M. The Economic Organization of U.S. Broiler Production; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service. Agriculture USD of Livestock and Poultry: World Markets and Trade; United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- Chicken Farmers of Canada. 2016 Annual Report. 2016. Available online: https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/300/ar_chicken_farmers/2016.pdf?nodisclaimer=1 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Grier, K. The 2015 Economic Impact of the Poultry and Egg Industries in Canada; Kevin Grier Market Analysis and Consulting Inc.: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hardie, J.M.; Whiley, R.A. Classification and overview of the genera Streptococcus and Enterococcus. Soc. Appl. Bacteriol. Symp. Ser. 1997, 26, 1S–11S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzauskas, M.; Siugzdiniene, R.; Spakauskas, V.; Povilonis, J.; Seputiene, V.; Suziedeliene, E.; Daugelavicius, R.; Pavilonis, A. Susceptibility of bacteria of the Enterococcus genus isolated on Lithuanian poultry farms. Vet. Med. 2009, 54, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, A.; Kühn, I.; Franklin, A.; Möllby, R. High Prevalence of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in Swedish Sewage High Prevalence of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in Swedish Sewage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2838–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byappanahalli, M.N.; Nevers, M.B.; Korajkic, A.; Staley, Z.R.; Harwood, V.J. Enterococci in the Environment. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 685–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Weng, X.; Li, H.; Yin, Y.; Pang, M.; Tang, Y. Enterococcus faecium -Related Outbreak with Molecular Evidence of Transmission from Pigs to Humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.R.; Coque, T.M.; Novais, C.; Hammerum, A.M.; Lester, C.H.; Zervos, M.J.; Donabedian, S.; Jensen, L.B.; Francia, M.V.; Baquero, F.; et al. Human and swine hosts share vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium CC17 and CC5 and Enterococcus faecalis CC2 clonal clusters harboring Tn1546 on indistinguishable plasmids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.P. The pathogenicity of enterococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1994, 33, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristich, C.J.; Rice, L.B. Enterococcal Infection—Treatment and Antibiotic Resistance. In Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection; Gilmore, M.S., Clewell, D.B., Ike, Y., Shankar, N., Eds.; Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Reik, R.; Tenover, F.C.; Klein, E.; McDonald, L.C. The burden of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections in US hospitals, 2003 to 2004. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 62, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, D.E.; Keller, N.; Barth, A.; Jones, R.N. Clinical Prevalence, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and Geographic Resistance Patterns of Enterococci: Results from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32 (Suppl. S2), S133–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Munita, J.M.; Arias, C.A. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in enterococci. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2014, 12, 1221–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jung, A.; Rautenschlein, S. Comprehensive report of an Enterococcus cecorum infection in a broiler flock in Northern Germany. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerlin, P.; Nicholson, V.; Brash, M.; Slavic, D.; Boyen, F.; Sanei, B.; Butaye, P. Diversity of Enterococcus cecorum from chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 157, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, B.L.; Rice, L.B. Intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms in enterococcus. Virulence 2012, 3, 421–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, M.; Diarra, M.S.; Checkley, S.; Bohaychuk, V.; Masson, L. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in Enterococcus spp. isolated from retail meats in Alberta, Canada. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 156, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegstad, K.; Mikalsen, T.; Coque, T.M.; Werner, G.; Sundsfjord, A. Mobile genetic elements and their contribution to the emergence of antimicrobial resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunny, G.M.; Berntsson, R.P.A. Enterococcal sex pheromones: Evolutionary Pathways to Complex, Two-Signal Systems. J. Bacteriol. 2016, 198, 1556–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, B. On Mobile Genetic Elements in Enterococci; Adding More Facets to the Complexity. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lett, M. Tn3-1ike elements: Molecular structure, evolution. Biochimie 1988, 70, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.B.; Carias, L.L.; Marshall, S.H. Tn5384, a composite enterococcal mobile element conferring resistance to erythromycin and gentamicin whose ends are directly repeated copies of IS256. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodel-Christian, S.L.; Murray, B.E. Characterization of the gentamicin resistance transposon Tn5281 from Enterococcus faecalis and comparison to staphylococcal transposons Tn4001 and Tn4031. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991, 35, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafede, M.E.; Carias, L.L.; Rice, L.B. Enterococcal transposon Tn5384: Evolution of a composite transposon through cointegration of enterococcal and staphylococcal plasmids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 1854–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System—Report 2016; Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Third Informational Supplement, M100-S23 ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vineetha, N.; Vignesh, R.; Sridhar, D. Preparation, Standardization of Antibiotic Discs and Study of Resistance Pattern for First-Line Antibiotics in Isolates from Clinical Samples. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2015, 1, 624–631. [Google Scholar]

- Woodford, N.; Egelton, C.M.M.D. Comparison of PCR with Phenotypic Methods for the Speciation of Enterococci. In Streptococci and the Host. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Horaud, T., Bouvet, A., Leclercq, R., de Montclos, H., Sicard, M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 405–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, R.; Yanke, L.J.; Church, D.; Topp, E.; Read, R.R.; McAllister, T.A. High-throughput species identification of enterococci using pyrosequencing. J. Microbiol. Methods 2012, 89, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchiya, T.T. Functional Cloning and Expression of emeA, and Characterization of EmeA, a Multidrug Efflux Pump from Enterococcus faecalis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 26, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, B.M.; Murray, B.E.; Weinstock, G.M. Characterization of emeA, anorA Homolog and Multidrug Resistance Efflux Pump, in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 3574–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Huda, M.N.; Kuroda, T.; Mizushima, T.; Tsuchiya, T. EfrAB, an ABC Multidrug Efflux Pump in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 3733–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavilla Lerma, L.; Benomar, N.; Sánchez Valenzuela, A.; Casado Muñoz Mdel, C.; Gálvez, A.; Abriouel, H. Role of EfrAB efflux pump in biocide tolerance and antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolated from traditional fermented foods and the effect of EDTA as EfrAB inhibitor. Food Microbiol. 2014, 44, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portillo, A.; Ruiz-Larrea, F.; Zarazaga, M.; Alonso, A.; Martinez, J.L.; Torres, C. Macrolide Resistance Genes in Enterococcus spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Li, G.; Wang, W. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Enterococcus species: A hospital-based study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 3424–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.V.; Weinstock, G.M.; Murray, B.E. An Enterococcus faecalis ABC homologue (Lsa) is required for the resistance of this species to clindamycin and quinupristin-dalfopristin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 1845–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.H.; Shin, E.S.; Kim, O.; Yoo, J.S.; Lee, K.M.; Yoo, J.I.; Chung, G.T.; Lee, Y.S. Characterization of two newly identified genes, vgaD and vatG, conferring resistance to streptogramin A in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 4744–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, M.; Beighton, D.; Philpott-howard, J.; Soltani, M.; Beighton, D.; Philpott-howard, J. Mechanisms of Resistance to Quinupristin-Dalfopristin among Isolates of Enterococcus faecium from Animals, Raw Meat, and Hospital Patients in Western Europe Mechanisms of Resistance to Quinupristin-Dalfopristin among Isolates of Enterococcus faecium fro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.M.; Hancock, L.E.; Gilmore, M.S. Mechanism of chromosomal transfer of Enterococcus faecalis pathogenicity island, capsule, antimicrobial resistance, and other traits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12269–12274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaard, A.E.; Willems, R.; London, N.; Top, J.; Stobberingh, E.E. Antibiotic resistance of faecal enterococci in poultry, poultry farmers and poultry slaughterers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 49, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.R.; English, L.L.; Carr, L.E.; Wagner, D.D.; Joseph, S.W. Multiple-Antibiotic Resistance of Enterococcus spp. Isolated from Comemercial Poultry Production Environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 6005–6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A. Unknown Risk on the Farm: Does Agricultural Use of Ionophores Contribute to the Burden of Antimicrobial. mSphere 2019, 4, e00433-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B.; Houlihan, A.J. Ionophore resistance of ruminal bacteria and its potential impact on. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesp, A.; Veldman, K.; van der Goot, J.; Mevius, D.; van Schaik, G. Monitoring antimicrobial resistance trends in commensal Escherichia coli from livestock, the Netherlands, 1998 to 2016. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24, 1800438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agunos, A.; Gow, S.P.; Léger, D.F.; Carson, C.A.; Deckert, A.E.; Bosman, A.L.; Loest, D.; Irwin, R.J.; Reid-Smith, R.J. Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance Indicators—Integration of Farm-Level Surveillance Data From Broiler Chickens and Turkeys in British Columbia, Canada. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanon, J.-B.; Jaspers, S.; Butaye, P.; Wattiau, P.; Méroc, E.; Aerts, M.; Imberechts, H.; Vermeersch, K.; Van der Stede, Y. A trend analysis of antimicrobial resistance in commensal Escherichia coli from several livestock species in Belgium (2011–2014). Prev. Vet. Med. 2015, 122, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L.; Agunos, A.; Gow, S.P.; Carson, C.A.; Van Boeckel, T.P. Reduction in Antimicrobial Use and Resistance to Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Escherichia coli in Broiler Chickens, Canada, 2013–2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2434–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, J.M.; Cardoso, M.F.; Moreira, F.A.; Müller, A. Phenotypic antimicrobial resistance (AMR) of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) from broiler breeder flocks between 2009 and 2018. Avian Pathol. 2022, 51, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theobald, S.; Etter, E.M.C.; Gerber, D.; Abolnik, C. Antimicrobial Resistance Trends in Escherichia coli in South African Poultry: 2009–2015. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2019, 16, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, O.; Alm, E.; Greko, C.; Bengtsson, B. The rise and fall of a vancomycin-resistant clone of Enterococcus faecium among broilers in Sweden. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 17, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persoons, D.; Dewulf, J.; Smet, A.; Herman, L.M.; Heyndrickx, M.; Martel, A.; Catry, B.; Butaye, P.; Haesebrouck, F. Prevalence and persistence of antimicrobial resistance in broiler indicator bacteria. Microb. Drug Resist. 2010, 16, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, A.R.; Michael, H.R.; Guangyu, Z.; Patrick, M.; Kinney, E.L.; Schwab, K.J.; Joseph, S.W. Lower Prevalence of Antibiotic-Resistant Enterococci on U.S. Conventional Poultry Farms that Transitioned to Organic Practices. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 1622–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emborg, H.-D.; Andersen, J.S.; Seyfarth, A.M.; Wegener, H.C. Relations between the consumption of antimicrobial growth promoters and the occurrence of resistance among Enterococcus faecium isolated from broilers. Epidemiol. Infect. 2004, 132, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diarra, M.S.; Rempel, H.; Champagne, J.; Masson, L.; Pritchard, J.; Topp, E. Distribution of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in Enterococcus spp. and characterization of isolates from broiler chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 8033–8043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnam, A.L.; Jackson, C.R.; Avellaneda, G.E.; Barrett, J.B.; Hofacre, C.L. Effect of Growth Promotant Usage on Enterococci Species on a Poultry Farm. Avian Dis. 2005, 49, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, F.J.; Sadurski, R.; Kray, A.; Boos, M.; Geisel, R.; Koöhrer, K.; Verhoef, J.; Fluit, A.C. Prevalence of macrolide-resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecium isolates from 24 European university hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 45, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Zhang, W.J.; Chu, S.; Wang, X.M.; Dai, L.; Hua, X.; Dong, Z.; Schwarz, S.; Liu, S. Novel plasmid-borne multidrug resistance gene cluster including lsa(E) from a Linezolid-Resistant Enterococcus faecium Isolate of Swine Origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7113–7116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendlandt, S.; Lozano, C.; Kadlec, K.; Gómez-Sanz, E.; Zarazaga, M.; Torres, C.; Schwarz, S. The enterococcal ABC transporter gene lsa(E) confers combined resistance to lincosamides, pleuromutilins and streptogramin A antibiotics in methicillin-susceptible and methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, G.; Klare, I.; Heier, H.; Hinz, K.H.; Böhme, G.; Wendt, M.; Witte, W. Quinupristin/dalfopristin-resistant enterococci of the satA (vatD) and satG (vatE) genotypes from different ecological origins in Germany. Microb. Drug Resist. 2000, 6, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, S.T.; Kadlec, K.; Schwarz, S. Novel ABC Transporter Gene, vga(C), Located on a Multiresistance Plasmid from a Porcine Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3589–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allignet, J.; Solh, E. Characterization of a new staphylococcal gene, vgaB, encoding a putative ABC transporter conferring resistance to streptogramin A and related compounds. Gene 1997, 202, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Science, E.; All, P.B.V.; Cedex, P. Sequence of a staphylococcal plasmid gene, vga, encoding a putative ATP-binding protein involved in resistance to virginiamyein A-like antibiotics. Gene 1992, 117, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Haroche, J.; Allignet, J.; Buchrieser, C.; Pathoge, M. Characterization of a Variant of vga(A) Conferring Resistance to Streptogramin A and Related Compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2271–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, I.T.; Banerjei, L.; Myers, G.S.A.; Nelson, K.E.; Seshadri, R.; Read, T.D.; Fouts, D.E.; Eisen, J.A.; Gill, S.R.; Heidelberg, J.F.; et al. Role of Mobile DNA in the Evolution of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science 2003, 299, 2071–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintiliani, R.; Courvalin, P. Characterization of Tn1547, a composite transposon flanked by the IS16 and IS256-like elements, that confers vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4281. Gene 1996, 172, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.B.; Thorisdottir, A.S. The prevalence of sequences homologous to IS256 in clinical enterococcal isolates. Plasmid 1994, 32, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primers | PCR Product | Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ddl1_F 5′-ATCAAGTACAGTTAGTCTT-3′ ddl1_R 5′-ACGATTCAAAGCTAACTG-3′ | ddlE. faecalis FOd | 941 | [31] |

| ddl2_F 5′-GCAAGGCTTCTTAGAGA-3′ ddl2_R 5′-CATCGTGTAAGCTAACTTC-3′ vanC1_F 5′-GGTATCAAGGAAACCTC-3′ vanC1_R 5′-CTTCCGCCATCATAGCT-3′ vanC2-F 5′-CTCCTACGATTCTCTTG-3′ vanC2-R 5′-CGAGCAAGACCTTTAAG-3′ | ddlE. faecium vanC1E. gallinarum vanC2 E. casseliflavus & E. flavescens | 550 822 439 | [31] [31] [31] |

| Ent-ES-211-233-F 5′-GHACAGAAGTRAAATAYGAAGG-3′ Ent-EL-74-95-R 5′-GGNCCTAABGTHACTTTNACTG-3′ emeA_F 5′-AGTATGATGTACTTAGCAATTTC-3′ emeA_R 5′-CATCTTATTTCGATTTAAAAATAAC-3′ efrA_F 5′-TTGGCTTTATGACGCCAGTG-3′ efrA_R 5′-CGTGCGATAGCTAAACGTTG-3′ efrB_F 5′-CCTTATTTAACTGGATTACCAAC-3′ efrB_R 5′-GAATAGTTGATAGGCGGTGG-3′ ermB_F 5′-ATTCTCAAAACTTTTTAACGAGTG-3′ ermB_R 5′-CCTCCCGTTAAATAATAGATAAC-3′ lsa_F 5′-CGTAAAGCTGCATCAATTTTGC-3′ lsa_R 5′-AATGGCTCCTGTATCAAAAATC-3′ mefA_F 5′-GGCAAGCAGTATCATTAATCAC-3′ mefA_R 5′-CATTATTGCACAGCAAACTACG-3′ vatG_F 5′-GTGGGAAAAGCATACACCT-3′ vatG_R 5′-TTGCAGGATTACCACCAAC-3′ vgaD_F 5′-CAACTGGAGCGAGCTGTTA-3′ vgaD_R 5′-GACAGCCGGATAATCTTTTG-3′ vatD_F 5′-GCTCAATAGGACCAGGTGTA-3′ vatD_R 5′-TCCAGCTAACATGTATGGCG-3′ vatE_F 5′-ACTATACCTGACGCAAATGC-3′ vatE_R 5′-GGTTCAAATCTTGGTCCG-3′ IS256c-F 5′-CATTGGTAAATTGGAATGGAAATC-3′ IS256c-R 5′-ATTCAAACATTTTTTCCTCTCC-3′ IS256d_F 5′-GATCAACTGGAGAATTAGTGTT-3′ IS256d-R 5′-CTCTAATATCCCCTAATGAAAATAATG-3′ | groES-EL spacer region emeA efrA efrB ermB lsa mefA vatG vgaD vatD/satA vatE/satG Primers flanking ef0125 Primers flanking ef0529 | variable (~200 bp) 1137 1048 1513 713 825 911 200 201 272 512 ~1173 ~1173 | [32] [33,34] [35,36] [35,36] [37,38] [39] [37,38] [40] [40] [41] [41] [42] [42] |

| IS256e_F 5′-GGCTATTTTTTAGCAAACTATGTAT-3′ IS256e_R 5′-CACAGCAACTATTGGTAACG-3′ | Primers flanking ef2187 | ~1173 | [42] |

| IS256f_F 5′-TGTCTAGCTAAAACGAAGCC-3′ IS256f-R 5′-GACCCAACAAAAGTAACTCG-3′ | Primers flanking ef2632 | ~1173 | [42] |

| IS256g-F 5′-CTGTTTTGTCTCGTCATTATATGA-3′ | Primers flanking ef3100 | ~1173 | [42] |

| IS256g-R 5′-GGTTATAGTAGGAATAATTTTGCC-3′ IS256h-F 5′-CTGAACTGACACAATTCATTAAAT-3′ | Primers flanking ef3215 | ~1173 | [42] |

| IS256h-R 5′-AATTTAGCAACATCTTTCATTGG-3′ | |||

| IS256t_F 5′-CTGAAAAGCGAAGAGATTCAAAGC-3′ | IS256 transposase | 748 | This study |

| IS256t_R 5′-GAACTTGGCATCTTTGCCAACTTAC-3′ |

| Pattern | 2015 | 2016 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis | E. faecium | E. faecalis | E. faecium | ||

| AMP-DOX-ERY | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| AMP-DOX-ERY-GEN-QD | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| AMP-DOX-ERY-STR-QD | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| AMP-DOX-LVX-NIT-QD | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| AMP-DOX-LVX-QD | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| AMP-ERY-QD | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| AMP-ERY-STR-QD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| DOX-ERY-GEN-QD | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| DOX-ERY-GEN-STR-QD | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| DOX-ERY-LVX-STR-QD | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| DOX-ERY-LZD-STR-QD | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| DOX-ERY-QD | 9 | 5 | 18 | 0 | 32 |

| DOX-ERY-STR | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| DOX-ERY-STR-QD | 11 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 18 |

| DOX-GEN-QD | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| DOX-STR-QD | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| ERY-LVX-QD | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ERY-NIT-QD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| ERY-STR-QD | 0 | 4 | 0 | 11 | 15 |

| ERY-NIT-QD-STR-TGC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| GEN-ERY-QD | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 37 | 17 | 29 | 16 | 99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tran, T.T.; Caffrey, N.; Grewal, H.; Wang, Y.; Cassis, R.; Mainali, C.; Gow, S.; Agunos, A.; Checkley, S.; Liljebjelke, K. Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Resistance Genes of Enterococci from Broiler Chicken Litter. Poultry 2025, 4, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry4030042

Tran TT, Caffrey N, Grewal H, Wang Y, Cassis R, Mainali C, Gow S, Agunos A, Checkley S, Liljebjelke K. Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Resistance Genes of Enterococci from Broiler Chicken Litter. Poultry. 2025; 4(3):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry4030042

Chicago/Turabian StyleTran, Tam T., Niamh Caffrey, Haskirat Grewal, Yuyu Wang, Rashed Cassis, Chunu Mainali, Sheryl Gow, Agnes Agunos, Sylvia Checkley, and Karen Liljebjelke. 2025. "Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Resistance Genes of Enterococci from Broiler Chicken Litter" Poultry 4, no. 3: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry4030042

APA StyleTran, T. T., Caffrey, N., Grewal, H., Wang, Y., Cassis, R., Mainali, C., Gow, S., Agunos, A., Checkley, S., & Liljebjelke, K. (2025). Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Resistance Genes of Enterococci from Broiler Chicken Litter. Poultry, 4(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry4030042