1. Introduction

Software engineering has always been a complex discipline, particularly because it depends on effective communication and collaboration among diverse stakeholders. Agile methodologies [

1,

2] have emerged to address this challenge by promoting empowerment, flexibility, and emergent design. However, in practice, software projects often extend beyond the scope of a single Agile team. They involve multiple organizations, regulatory authorities, and business units, each with distinct roles (e.g., those who commission a software artifact, those responsible for gathering requirements, those designing specifications, those developing the software, and those validating its functionality) and priorities. While Agile ceremonies such as retrospectives, backlog refinement, and planning events support intra-team alignment, they may not fully resolve misalignments across organizational and stakeholder boundaries. Indeed, each of these actors could perceive the software engineering process differently, shaped by their individual mental models and specific roles. As a result, they tend to execute the process or influence others in ways that align with their own priorities and goals.

The ultimate objective of an organization is to synthesize these diverse perspectives to deliver software that balances business value, regulatory compliance, and stakeholder needs. Achieving such alignment is challenging, even in Agile environments, as individuals may pursue conflicting objectives or interpret requirements differently. Standard Agile practices provide effective mechanisms for local adaptation but offer limited guidance for reconciling divergent perspectives across distributed enterprises and regulated domains. This creates a gap where organizational agility requires complementary tools for achieving higher-level alignment without undermining team autonomy. Even when different versions of the process exist and are available, there is no standardized methodology to quantify which elements should be preserved or adapted.

Existing modeling frameworks, such as the Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM) [

3,

4] and the Work-As-x (WAx) framework [

5], capture multiple stakeholder views and help analyze variability in socio-technical systems. Recent work in stakeholder alignment and model-driven engineering [

6] also contributes to this discussion. Yet, none of these approaches explicitly operationalize consensus-building in a way that integrates with Agile principles or provides quantifiable support for decision-making. This motivates the need for an integrated methodology that enhances Agile practices in contexts of organizational complexity.

This paper proposes a methodology and an accompanying software tool to facilitate alignment-oriented synthesis of software processes in Agile contexts characterized by diverse stakeholders. The approach begins with stakeholder-specific process instances and employs an iterative, inspect-and-adapt methodology, grounded in systematic comparisons. By leveraging quantifiable performance indicators, the framework guides stakeholders toward convergence on a Shared Alignment Artifact (SAA), complementing Agile ceremonies by capturing perspectives that extend beyond the boundaries of single teams. The resulting artifact integrates valuable contributions from each stakeholder while preserving Agile values of transparency, empowerment, and adaptability.

After identifying all relevant stakeholders, individual interviews are conducted to prevent influential actors within the organizations from imposing their own perspectives or mental models on others. Subsequently, the interviews are translated into instances using FRAM. Then, the software tool allows users to establish inter-instance couplings between elements within these process instances.

During the phase referred to as the iterative-corrective process, if substantial discrepancies arise between the various instances, the stakeholders are interviewed collectively, in an effort to harmonize the instances as much as possible. However, a clear chronology of the changes is maintained, thanks to the previously conducted individual interviews, thus preserving the original individual perspectives.

Finally, the synthesis process is determined either through consensus or by utilizing process performance indicators. Rather than relying on subjective judgments, the approach employs quantifiable metrics to ensure objective and replicable outcomes. Indeed, our approach extends beyond conventional software quality metrics by integrating broader performance indicators, including enhanced business efficiency, resource optimization, time management, and sustainability considerations. These indicators offer quantifiable evidence of each function’s contribution within the software engineering workflow and are used to compute an overall process performance coefficient that supports balanced and informed decision-making, even in scenarios where stakeholders are unavailable or in disagreement.

This work extends Agile-at-scale practices in contexts characterized by (i) multiple organizations and supplier relationships, (ii) high regulatory oversight, and (iii) cross-domain complexity. We do not replace Agile team empowerment or ceremonies; rather, we complement them with a Shared Alignment Artifact, an evidence-supported, cross-stakeholder view that helps maintain alignment across organizational boundaries when team-level mechanisms (e.g., retrospectives, backlog refinement, PI planning) are insufficient on their own.

To clarify the academic contribution of this work, we emphasize that the proposed methodology does not merely restate existing Agile practices or process-modeling approaches. Instead, it introduces three key advancements. First, it provides a systematic, multi-perspective process synthesis mechanism, designed to produce a Shared Alignment Artifact, that integrates the diverse and often divergent representations held by different stakeholders, using FRAM and WAx to structure and relate these perspectives. This enables the explicit comparison and reconciliation of divergent stakeholder mental models, an element not operationalized in prior literature. Unlike traditional process synthesis, which typically aims to merge or optimize process models at a technical level, the Shared Alignment Artifact represents a negotiated, evidence-supported consensus among stakeholders, preserving their individual perspectives while producing a unified and operational process representation. Second, the methodology incorporates a novel evidence-supported decision layer based on quantifiable performance indicators, which guides or resolves cross-stakeholder negotiations and offers a fallback mechanism when consensus cannot be reached. Third, we operationalize this methodology in a working software tool that automates function pairing, tuple creation, performance coefficient evaluation, and Shared Alignment Artifact extraction, allowing the approach to be deployed in real industrial contexts. Together, these contributions provide a complementary alignment mechanism that strengthens Agile-at-scale practices in environments characterized by organizational complexity, regulatory oversight, and heterogeneous stakeholder goals.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces a motivation scenario drawn from the software gaming industry.

Section 3 situates the contribution within the context of Agile and related research.

Section 4 provides necessary background.

Section 5 details the proposed methodology, while

Section 6 describes the supporting tool.

Section 7 presents the experimentation conducted, and

Section 8 reflects on the advantages and limitations of the methodology, particularly regarding its qualitative validation in a real industrial setting and the challenges of conducting broader quantitative studies. Finally,

Section 9 concludes with key lessons learned and directions for future work.

2. Motivation Scenario

One of the persistent challenges in software engineering, even in Agile environments, is reconciling the perspectives of diverse stakeholders. Agile practices such as retrospectives and backlog refinement help individual teams align, but when multiple organizations, business units, or regulated domains are involved, achieving cross-stakeholder alignment becomes more difficult. In these contexts, mechanisms for systematically synthesizing perspectives are needed to complement Agile ceremonies and maximize value for the organization.

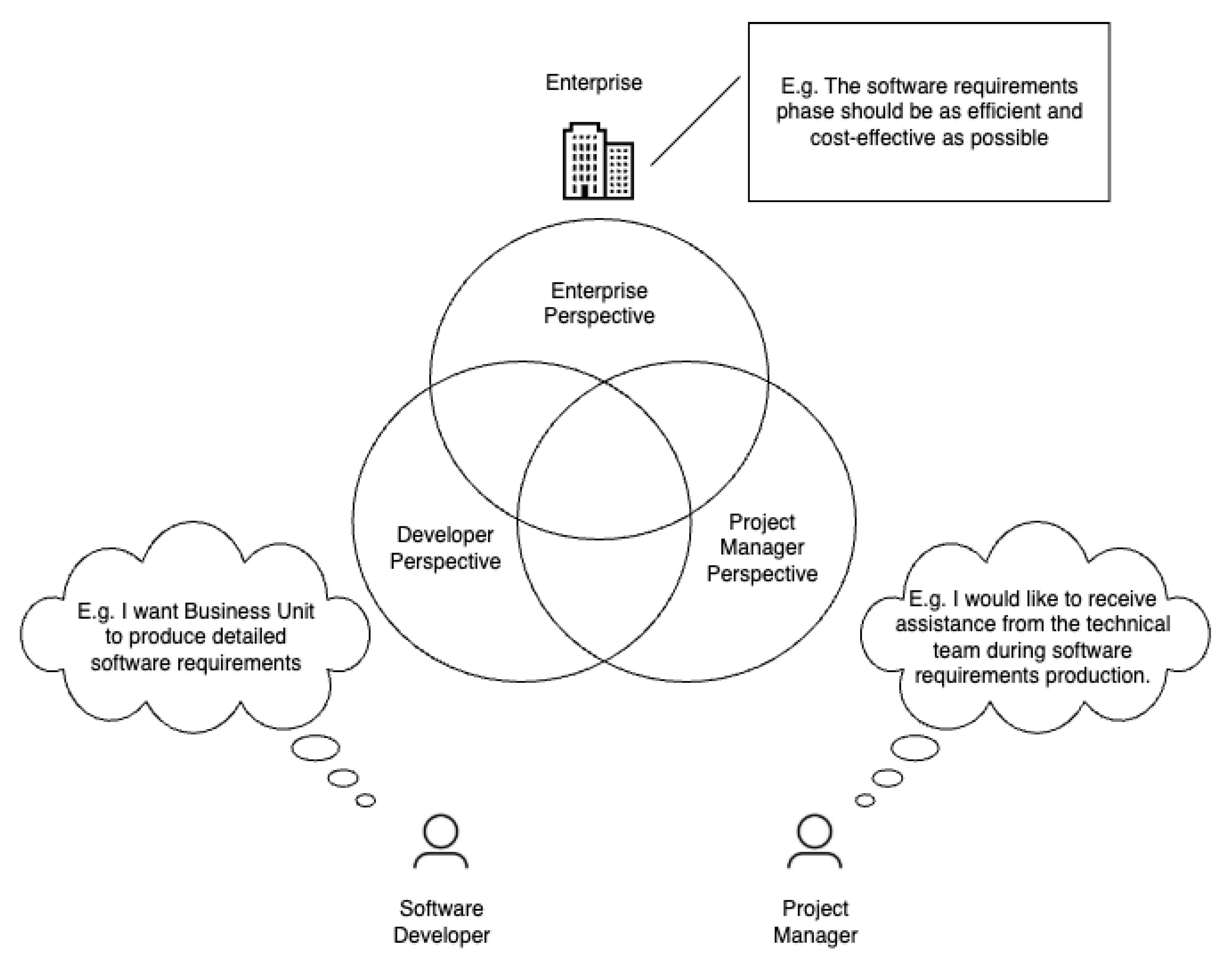

Figure 1 illustrates an example of two actors typically involved in software engineering. Each actor brings their own goals and interests, which may or may not align (depicted as the intersection of sets). While Agile ways of working promote transparency and team empowerment, the product resulting from the process must also create value for the organization as a whole, value that may not fully coincide with the individual goals of each stakeholder.

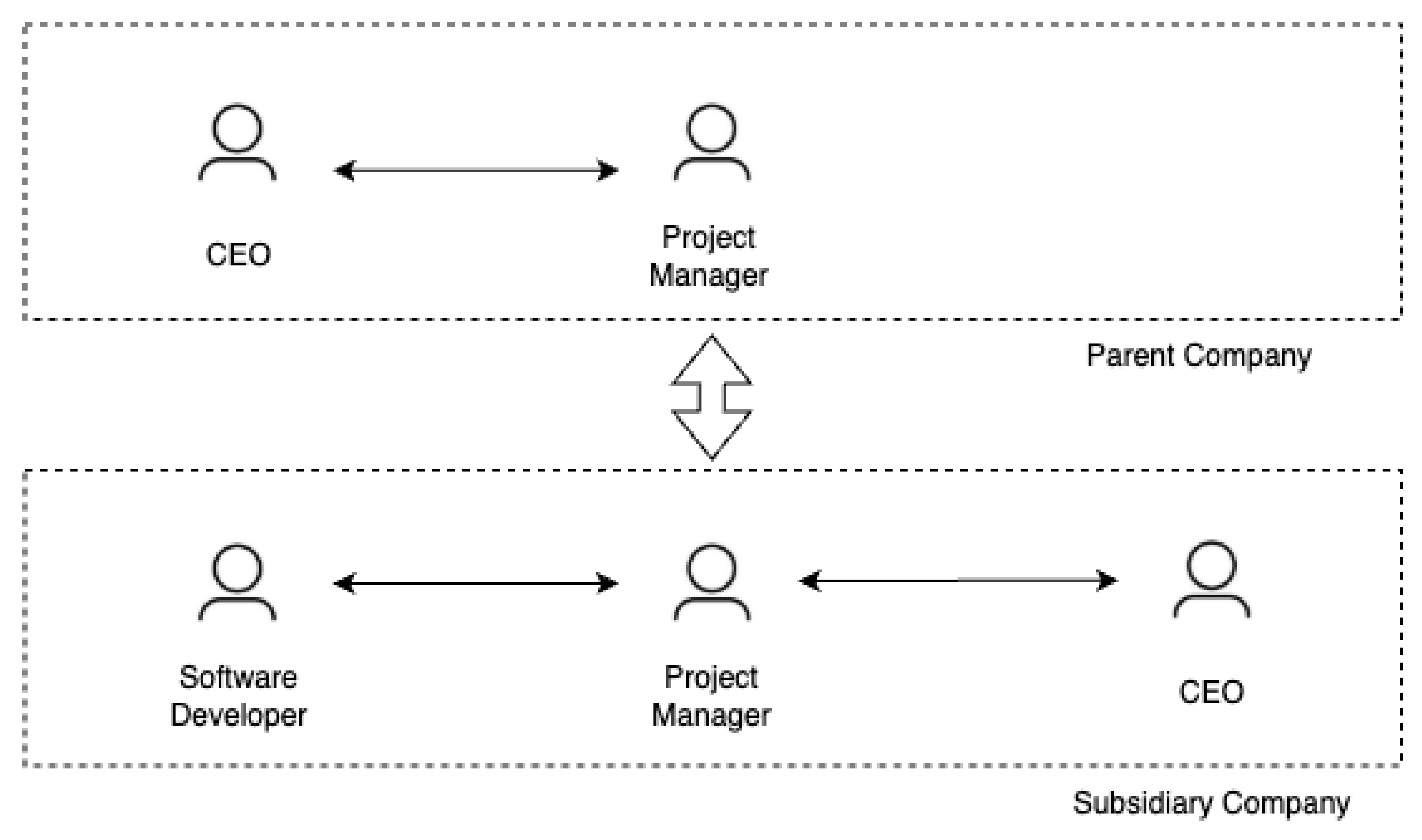

Figure 2 provides a more realistic view of modern organizational contexts. In such environments, stakeholders are distributed across multiple entities linked through parent–subsidiary relationships. Scaled Agile frameworks such as SAFe [

7] or LeSS [

8] provide mechanisms for multi-team coordination, yet challenges persist when stakeholders hold fundamentally different perspectives shaped by managerial, technical, or regulatory roles. Standard Agile events are not always sufficient to capture and reconcile these systemic misalignments.

To validate the hypotheses and tools developed in this work, we observed a real organization operating in the gaming industry. This company consists of several subsidiaries, each specializing in a different sector, and faces ongoing challenges in digitizing operations and managing projects across subsidiaries. The primary difficulties involve communication between actors with diverse backgrounds and the alignment of goals across different organizational units.

One subsidiary, focused on the land-based market, produces products that integrate traditional gaming systems with physical cabinets, while also introducing innovative features such as decentralized gaming logic, real-time monitoring of casino KPIs, and personalized gaming experiences. The parent company coordinates these projects through a lead project manager, who works closely with a counterpart in the subsidiary. Both managers share a more managerial perspective, focusing on requirements, task assignment, and validation, while developers hold a more technical perspective oriented toward software implementation. This divergence illustrates a gap: Agile ceremonies ensured team-level progress but did not guarantee alignment across business, managerial, and technical domains.

The software development process in this organization follows a sequence of activities that resemble Agile practices. The business unit defines initial requirements, which are then refined in a way similar to backlog refinement by the project management team and later revised by the technical team. A feasibility study is conducted to assess available resources and timing, comparable to sprint or release planning. The findings are returned to the business unit, which approves or rejects development. If approved, the technical team produces detailed specifications, develops the solution, and performs internal testing before releasing it to the business unit for final evaluation. After further validation, including regulatory certification, the solution is deployed to production.

Although iterative feedback loops and reviews were in place, misalignments persisted across the different levels of the organization. Stakeholders interpreted requirements differently, prioritized competing goals, and evaluated quality using distinct criteria. Agile practices alone did not provide sufficient mechanisms to reconcile these perspectives across organizational and regulatory boundaries. This case study therefore demonstrates the need for structured, quantifiable methods that complement Agile ways of working by enabling consensus-building and alignment at scale, without undermining the flexibility and empowerment central to Agile.

3. Related Work

This paper explores several key themes, including agile frameworks and their limitations, the alignment of process perspectives within organizations, stakeholder collaboration, consensus, and alignment in software engineering, business and IT alignment, digital transformation in enterprises, process synthesis and re-engineering, and software development and teamwork methodologies. These themes are outlined below.

3.1. Agile Frameworks and Their Limitations

Agile methodologies such as Scrum and Kanban have become the de facto standards for managing software development projects, emphasizing empowerment, flexibility, and iterative delivery [

9]. These approaches are highly effective for single-team contexts, where alignment can be achieved through ceremonies such as sprint planning, backlog refinement, and retrospectives. However, as organizations scale, new challenges emerge that go beyond the boundaries of individual teams.

To address these challenges, several scaled Agile frameworks have been introduced. Large-Scale Scrum (LeSS) [

8] extends Scrum principles to multiple teams working on the same product, while the Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) [

7] provides structured practices for coordinating large programs across organizational layers. The Spotify model [

10] emphasizes autonomy and alignment through organizational units such as tribes, squads, chapters, and guilds. These frameworks provide mechanisms for multi-team coordination, dependency management, and organizational scaling.

Nevertheless, despite their strengths, these frameworks still face limitations in contexts where stakeholders come from heterogeneous organizations, subsidiaries, or regulatory authorities. Standard Agile ceremonies may not fully capture tacit knowledge, reconcile conflicting managerial and technical perspectives, or provide quantifiable evidence for decision-making across organizational boundaries. Our work addresses this gap by proposing a methodology that complements Agile frameworks: it systematically integrates diverse stakeholder perspectives into a consensus-driven alignment artifact, thereby strengthening Agile ways of working without undermining flexibility and team autonomy.

3.2. Alignment of Process Perspectives in Organizations

Some of the most relevant contributions in this area include Model repair [

11], which introduces a methodology for reconstructing a process as it happened from its traces (log) and aligning the theoretical process as closely as possible with the one that actually occurred. Additionally, techniques based on system dynamics [

12] aim to explain why misalignment between business and IT arises. Baker & Singh [

12] do not impose a-priori constraints regarding which departments or stakeholders should be included when investigating misalignment. More recently, techniques [

13,

14] based on the use of large language models aim to identify key elements from the text as a preliminary step to build a shared process model. Finally, many approaches to studying complex systems rely on methodologies that use incentives or rewards to encourage actors to align toward a common goal [

15,

16]. However, in real-world scenarios, particularly in complex organizational settings, actors may pursue objectives that are not strictly aligned or may even be in direct conflict with one another.

Unlike these approaches, the methodology in our paper does not seek to adapt one process instance to another. Instead, it aims to synthesize a consensual process that incorporates and balances the perspectives of all stakeholders involved, enriching the final process with their collective insights.

3.3. Stakeholder Collaboration, Consensus, and Alignment in Software Engineering

Several recent studies have examined the challenges and practices associated with collaboration, consensus, and alignment among stakeholders in software engineering projects.

David et al. [

17] present a systematic survey of collaborative model-driven software engineering (MDSE) in industry, highlighting the complexity of engineering software-intensive systems in collaboration with stakeholders from diverse backgrounds. Their mixed-method survey reveals gaps between academic research and industry needs, emphasizing the importance of tools and methodologies that support effective stakeholder collaboration throughout the software development lifecycle.

The impact of stakeholder management on project outcomes is further explored by Oliveira and Rabechini [

18], who quantitatively analyze how stakeholder management practices influence trust within project environments. Their findings demonstrate that relational stakeholder management significantly enhances different types of trust, reinforcing the critical role of communication and engagement in successful project execution.

Focusing on organizational technology acceptance, Sarkeshikian et al. [

19] develop and empirically validate a model of essential activities and characteristics for advocates who accelerate stakeholder consensus. Their work applies thematic analysis and structural equation modeling to identify key factors for achieving consensus in technology adoption, underscoring the necessity of structured consensus-building processes.

Buchan et al. [

6] investigate the alignment of stakeholder expectations regarding user involvement in Agile software development. Through an exploratory case study and the use of repertory grids, they reveal that misalignment between the expectations of developers and users can lead to conflicts and ineffective user participation, and propose instruments to assess and enhance alignment throughout Agile projects. This connects to broader efforts in scaled Agile frameworks (see section on Agile Frameworks), which address coordination but still lack mechanisms for systematic consensus-building.

Collectively, these studies underline the ongoing need for methodologies that foster collaboration, alignment, and consensus among stakeholders.

In contrast to prior work, our approach provides a systematic, tool-supported methodology that explicitly synthesizes a consensus-driven representation of the software process, hereafter referred to as the Shared Alignment Artifact (SAA). Unlike prior studies, which primarily focus on mapping practices, analyzing trust, or identifying factors affecting consensus and alignment, our work provides a quantifiable, stepwise process for reconciling and integrating the diverse perspectives of all stakeholders. The proposed methodology goes beyond descriptive or diagnostic frameworks by enabling the concrete construction of a unified process model, guided by objective performance indicators and supported by an operational software tool. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first approach to formalize and automate the creation of a consensus-driven process model tailored to the specific context and stakeholder group of a software engineering project.

3.4. Business and IT Alignment

Business and IT alignment is a critical factor in enhancing organizational performance and agility. Reich and Benbasat [

20] emphasize the importance of shared domain knowledge, effective communication, and trust between business and IT executives as key drivers of alignment. Luftman and Brier [

21] further identify strong leadership, senior management support, and mutual understanding as essential enablers for achieving and sustaining business and IT alignment.

Kearns and Sabherwal [

22] propose a knowledge-based view, highlighting that top management’s IT knowledge and cross-participation in planning processes significantly influence strategic alignment. Liang et al. [

23] explore the dual dimensions of alignment. They define intellectual alignment as the degree to which business and IT executives share a common understanding of the organization’s strategic objectives and the role of IT in achieving those objectives while social alignment is characterized by informal relationships, mutual trust, and shared values between business and IT leaders. Their study reveals that while intellectual alignment can impede agility by increasing inertia, social alignment enhances agility through improved coordination.

To address the dynamic nature of modern enterprises, Hinkelmann et al. [

24] introduce a paradigm combining enterprise architecture modeling and enterprise ontology, facilitating continuous alignment in rapidly changing environments. Rahimi et al. [

25] underscore the necessity of integrating business process management with IT management to ensure cohesive strategic and operational alignment.

Collectively, these studies underscore that successful business and IT alignment requires a multifaceted approach, integrating strategic planning, organizational culture, and continuous adaptation to technological advancements.

With respect to the mentioned studies, our paper proposes a new, operational, and software-supported methodology for achieving alignment and consensus among stakeholders in software engineering projects. Unlike classic business and IT alignment frameworks that focus on strategic alignment or assume alignment can be achieved through communication and leadership, our approach dives deep into process-level perspectives, uses structured and iterative negotiation, quantifiable performance indicators, and algorithmic consensus extraction. It is therefore a significant extension and operationalization of alignment, moving from high-level strategy to actionable process design and real-world conflict resolution among diverse stakeholders. Then, our approach operationalizes alignment within Agile transformation programs, not just traditional IT governance.

3.5. Digital Transformation in Organizations

Knowledge is an invaluable asset for all organizations, particularly in the execution of processes. While the digitization of knowledge has posed significant challenges, it has also required the establishment of foundational principles to guide this transition, such as alignment with knowledge management strategies and human-centric knowledge capture [

26,

27].

An essential benefit of digital transformation within organizations is its role in transforming tacit knowledge, often embedded in individual experiences and difficult to articulate, into explicit, sharable forms. Tacit knowledge is a key asset in knowledge-intensive teamwork and innovation processes, but it is frequently underutilized due to its implicit nature [

28]. Digital tools and structured methodologies create the conditions for capturing this knowledge through collaborative activities such as process modeling, stakeholder interviews, and systems-based representations. Pyrko et al. [

29] emphasize the importance of “thinking together” within Communities of Practice as a way to surface and share tacit knowledge. Similarly, Ganguly et al. [

30] demonstrate how tacit knowledge sharing directly contributes to an organization’s innovation capability. By supporting these dynamics, digital transformation enables not only operational improvements but also the formalization and long-term reuse of experiential knowledge that is critical to complex socio-technical systems like software engineering.

The methodology in our paper serves as a potential tool for supporting knowledge management, specifically by encoding knowledge from specific actors during the interview phase, which provides a valuable opportunity to convert tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge [

5]. The software architecture, built based on the described methodologies, generates ontologies [

31] that represent the domains in which the application operates. As a result, the accumulated knowledge becomes an asset with economic value for the organization. Finally, the last confrontation between stakeholders fosters a moment of knowledge sharing, which may not naturally occur in the organization’s regular workflow.

3.6. Process Synthesis and Re-Engineering

Process re-engineering has been a prominent and widely discussed topic since the 1990s [

32]. While the methodologies proposed in process re-engineering share some common objectives with the goals of the Shared Alignment Artifact, such as reducing costs and increasing efficiency, their underlying premises are fundamentally different. In process re-engineering, the focus is on analyzing the organization as a whole, studying the processes that constitute the entire system [

32]. In contrast, the proposed methodology centers on examining one process at a time in detail. Additionally, in process re-engineering, technology is primarily used as an optimization tool to eliminate unnecessary processes without necessarily automating them [

32]. The Shared Alignment Artifact, however, is positioned at a later stage, once processes have been established and actors are already involved. The starting premises differ as well: the SAA is rooted in the mental models of the actors and does not aim to eliminate processes. Furthermore, process re-engineering typically begins with clear organizational goals, seeking to radically redefine the processes that make up the organization [

32,

33]. On the other hand, the SAA methodology has no predefined objectives beyond creating a process that incorporates the best contributions from all stakeholders. Unlike process re-engineering, Agile emphasizes emergent adaptation through iterative feedback; our methodology extends this by adding structured, cross-stakeholder consensus mechanisms. In summary, while Scrum, SAFe, LeSS, and the Spotify model provide effective mechanisms for intra- and inter-team coordination, they offer limited operational guidance for synthesizing divergent stakeholder perspectives across organizational and regulatory boundaries using quantifiable evidence. Our SAA explicitly targets this gap, operating alongside Agile ceremonies to preserve team autonomy while enabling system-level alignment.

3.7. Distinction from Existing Software Development and Teamwork Methodologies

The proposed methodology fundamentally differs from classical software development, requirements engineering, and teamwork approaches such as CASE tools [

34], Use Case Analysis [

35], Joint Application Design (JAD) [

36], and Function Point Analysis [

37]. Traditional software development methodologies (e.g., Use Case Analysis, JAD) focus on eliciting, structuring, or validating requirements for the system under development. Their goal is to model what the system should do, typically assuming a shared understanding among participants or constructing it through facilitated sessions. In contrast, our methodology addresses a different problem: the systematic reconciliation of heterogeneous representations of the development process itself, that is, how different stakeholders believe the process operates. As stated in the manuscript, organizational actors often hold divergent perspectives shaped by their roles, experiences, and priorities.

Our approach is therefore not a requirements-elicitation technique but a process-alignment and consensus-building mechanism. CASE tools provide automated support for creating and maintaining software artifacts such as diagrams, specifications, and code. They assume that a single, agreed-upon process model already exists and focus on artifact-level engineering productivity. Our contribution instead operates before such tools: it generates a SAA by comparing and synthesizing multiple, potentially conflicting process instances gathered from interviews (individual WAD/WAI perspectives). The methodology explicitly models variability through FRAM functions and WAx entities, preserving tacit knowledge and contextual dependencies not captured by CASE tools.

Unlike process re-engineering or optimization methodologies, which begin with predefined organizational goals such as cost reduction or cycle-time improvements, our method has no prescriptive objective function. As clarified in the manuscript, it seeks to synthesize a process that reflects the collective mental models of stakeholders, without eliminating process steps or imposing top-down redesign criteria. The central aim is alignment, not efficiency-driven transformation.

Classical methods also do not provide a quantitative fallback mechanism when stakeholders fail to reach agreement. Our methodology introduces a novel evidence-supported evaluation based on multi-category performance indicators (sustainability, quality, business value, resource usage, CIA security, and others) and computes a function-level performance coefficient. This enables the automatic selection of the best-supported function within each tuple using the evidence-supported algorithm outlined in the manuscript. Such algorithmic consensus support is not present in JAD, Use Case Analysis, Function Points, or CASE tools.

Finally, the methodology produces not only a conceptual framework but also a fully implemented software tool that integrates semantic pairing of functions via NLP, automated identification of tight and loose couplings, guided indicator weighting, and evidence-driven SAA extraction through a shortest-path formulation. To our knowledge, no existing methodology operationalizes cross-stakeholder alignment through a comparable combination of FRAM, WAx, quantitative indicators, and algorithmic synthesis.

In summary, the proposed methodology is not an alternative to classical software development approaches; instead, it addresses a missing capability in Agile and large-scale software organizations: the ability to systematically capture, compare, and reconcile diverse process perspectives across organizational, managerial, and regulatory boundaries. This unique purpose, combined with the evidence-supported synthesis mechanism, constitutes the key innovation and principal improvement over existing methodologies.

4. Knowledge Background

4.1. The Functional Resonance Analysis Method

The first step is to select a method for representing the different instances of the software development process. There are several options available, and among them, we chose the FRAM. This allows us to represent the individual functions that make up a process instance (and their interrelations) and, most importantly, the dependencies that exist between them, based on six aspects: input, output, time, resource, precondition, and constraint. This feature is crucial for constructing the synthesis process (i.e., SAA), which will likely incorporate features from different instances. Therefore, it is important to carry over all the preconditions into the SAA to ensure no valuable information about the details of the final process is lost.

FRAM was developed to model and analyze complex socio-technical systems, especially where traditional linear or component-based methods fall short. Unlike approaches that require decomposition into fixed sequences or rigid structures, FRAM is inherently flexible and does not impose a predetermined model. Instead, it focuses on describing a system in terms of what it does, its functions and how they are coupled, rather than what it is structurally. This makes FRAM particularly suitable for representing processes as they are actually carried out (“Work-As-Done”), rather than how they should ideally be performed (“Work-As-Imagined”). Such elasticity simplifies analysis by allowing representations to be generated quickly and iteratively.

A key strength of FRAM is its ability to address the variability and complexity typical of real-world processes. It recognizes that both successes and failures originate from the same system dynamics, and that outcomes often emerge from the interactions among multiple functions, rather than from isolated failures or events. This makes it possible to capture not just how individual functions behave, but also how their couplings and dependencies might give rise to unexpected behaviors or emergent outcomes. In this way, FRAM supports a holistic and non-linear view of process modeling, which is particularly valuable when analyzing and synthesizing software development processes that span diverse contexts. By employing FRAM, we are able to maintain focus on the relevant aspects of the system, while also accommodating the natural variability and dynamic interrelations inherent in complex development environments.

4.2. The WAx Modeling Framework

The WAx modeling framework is a conceptual framework designed to analyze Cyber-Socio-Technical Systems (CSTS), where both technology and social interactions play a crucial role. Within this framework, knowledge entities represent the specific knowledge being referred to. This enables the analysis of the same process from multiple perspectives, for example, from the viewpoint of actors directly involved in the process, represented by the Work-As-Done (WAD), or from the perspective of those overseeing it, represented by the Work-As-Imagined (WAI) [

5].

When two instances of the same process, such as WAI and WAD, are present, achieving a SAA becomes beneficial. Once these instances are gathered (e.g., through interviews and their transcription into FRAM), the next step is to identify functions with the same meaning across instances. These functions will naturally be part of the process where consensus is reached.

To match functions, we can use the previously mentioned FRAM aspects, time, resource, precondition, constraint, input, and output, which help identify pairs of related functions when comparing two process instances, or tuples of related functions when more instances are involved, depending on the number of instances collected [

31]. It is important to note that, throughout the remainder of this paper, the term tuple refers exclusively to this concept. The combination of these elements defines different degrees of coupling between functions.

4.3. Existing Frameworks for Measuring Process Performance

Lastly, as mentioned earlier, reaching a SAA becomes extremely challenging when multiple actors with different priorities are involved, especially within a finite timeframe. Therefore, it is essential to define reliable metrics to assess how one function within a tuple compares to the others, whether it performs better or worse. These metrics serve as a guide to facilitate (or, in extreme cases, enforce) the achievement of a SAA.

The proposed indicators have been derived from some of the most widely used frameworks for evaluating products and processes, including software. Examples include COCOMO II [

38], a well-known model for estimating the effort required to develop software; the CIA [

39] security principles; methodologies from business administration and risk management; as well as indicators related to Industry 5.0 [

40] and sustainability, topics of particular relevance and current significance.

The proposed methodology leverages the modeling capabilities of FRAM, the systemic analytical lens of WAx, and established frameworks for evaluating process performance, integrating them into a unified approach that supports the comparative analysis, reconciliation, and consensus-driven synthesis of software engineering processes through quantifiable indicators and model harmonization strategies. Finally, the proposed approach automates parts of this synthesis via a software tool that supports both interactive and fallback consensus extraction.

5. A Methodology for Building Shared Alignment in Agile Contexts

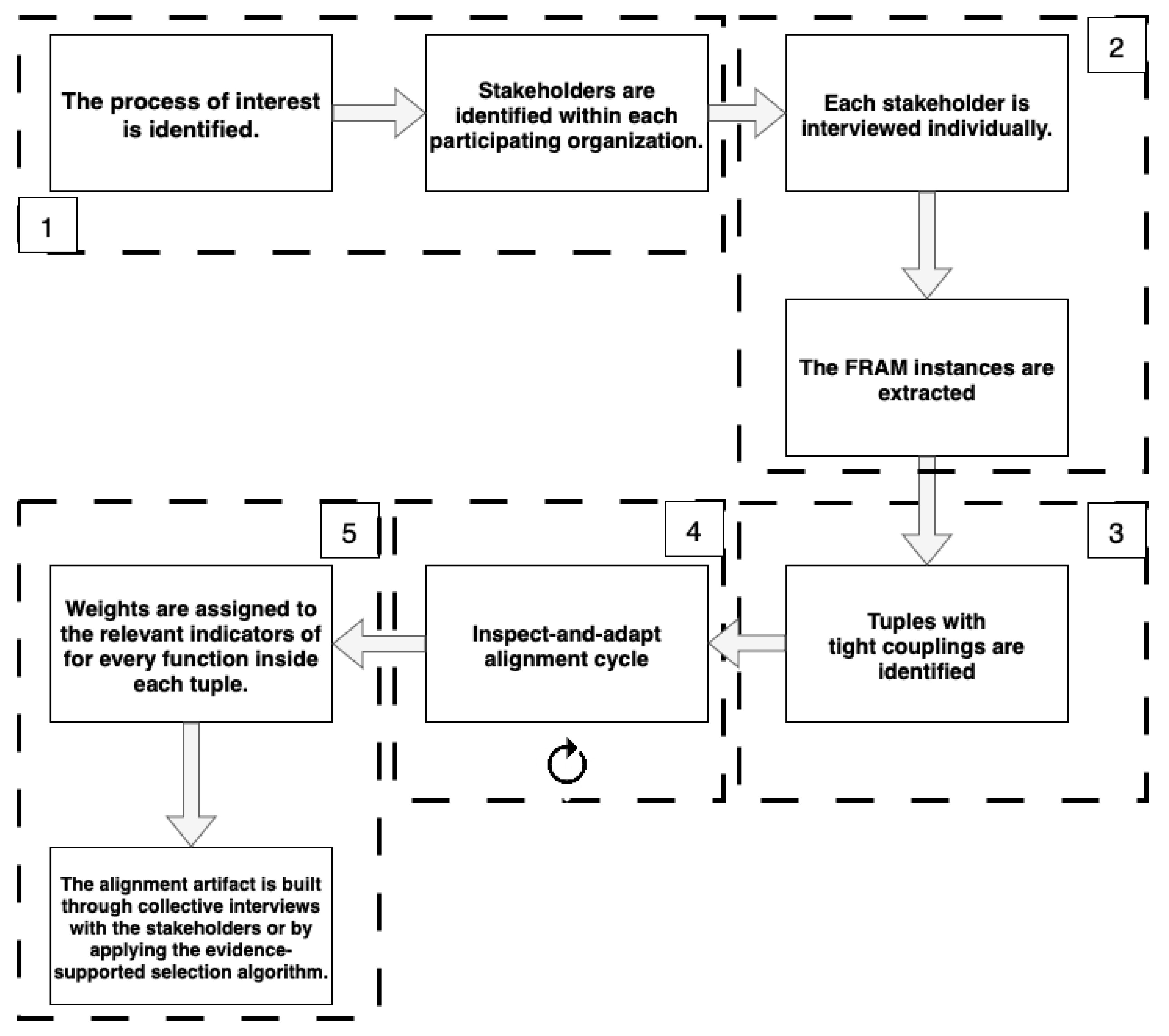

The alignment-building methodology in software engineering is summarized in

Figure 3 and is structured into five main steps, each of which is explained in detail in the following subsections:

- 1.

Process and actor identification;

- 2.

Modeling process instances;

- 3.

Identifying inter-instance functional couplings;

- 4.

Inspect-and-adapt (iterative-corrective) alignment cycle;

- 5.

Creating a Shared Alignment Artifact through evidence-supported selection.

The outcome of the methodology is a Shared Alignment Artifact, a consolidated, evidence-supported view of the process that complements Agile ways of working (e.g., backlog refinement, sprint planning, and retrospectives) without replacing them.

We assume Agile (Scrum/Kanban) teams, potentially operating within scaled frameworks (e.g., SAFe, LeSS). The methodology for building SAA complements, rather than replaces, ceremonies such as backlog refinement, sprint planning, reviews, and retrospectives by externalizing cross-stakeholder constraints and evidence needed for decisions that span organizational boundaries.

5.1. Process and Actor Identification

The first step is to identify the process of interest and the relevant actors. As mentioned, we need at least two perspectives, such as one from those who manage or supervise the process and another from those who implement it. In the context of software development, the typical actors are project managers, technical managers, developers, analysts, team leaders, and any other stakeholders whose goal achievement depends on the process. Importantly, these actors may belong to different organizational units or even entirely separate organizations, especially in collaborative, distributed, or outsourced projects. For example, in a software supply chain involving a vendor and a client organization, process ownership may be split between a development team contracted by the vendor and a deployment or operations team on the client side. Similarly, in regulated industries such as healthcare or gaming, external auditors or compliance officers may act as additional stakeholders influencing or constraining the development process. The methodology is thus also designed to accommodate such multi-organizational settings, ensuring that the diverse roles and priorities are represented from the outset. This step complements Agile backlog (i.e., the list of features, user stories, and tasks) refinement by ensuring that not only team-level perspectives (e.g., developers, product owners) but also cross-organizational stakeholders (e.g., regulators, business managers) are represented.

5.2. Modeling Process Instances

Once at least two relevant actors have been identified, for instance, one from management and one from operations, individual interviews are conducted to prevent cross-contamination of perspectives. It is crucial to capture each actor’s personal view of the process. For those directly involved in execution, the focus should be on how the process is actually implemented rather than on how it is theoretically supposed to function. For those in supervisory roles, the emphasis should be on their perception of how the process is carried out.

Once the interviews are completed, process instances are labeled using WAx knowledge entities and functions and aspects are specified according to the FRAM method. The sharp-end operators focus on WAD, while the blunt-end operators concentrate on WAI.

At this stage, it is crucial to identify the relationships between the functions, considering both their sequentiality, i.e., the temporal order in which process functions occur, and their consequentiality, i.e., how one function serves as a precondition or constraint for another, among other dependencies.

This provides a structured way to surface tacit knowledge and build a shared understanding, strengthening Agile practices such as backlog refinement and sprint planning by giving visibility to perspectives that would otherwise remain implicit.

5.3. Identifying Inter-Instance Functional Couplings

Once pairs or tuples, depending on the number of available process instances, are identified across the different instances based on their semantic meaning, functions of each pair or tuple should be enriched with FRAM aspects. Analyzing this information results in different degrees of coupling, namely tight coupling and loose coupling. Tight coupling occurs when the functions within a tuple share not only a similar meaning but also matching FRAM aspects (see

Table 1). In the context of selecting the functions that will constitute the final SAA, any function from a tightly coupled tuple may be selected, as they effectively represent the same function due to their shared semantics and FRAM aspects. In contrast, loose coupling arises when the functions have a similar meaning, yet one or more FRAM aspects do not align (see

Table 2). In cases of loose coupling, as well as for functions that remain uncoupled, human intervention is required to validate the output.

5.4. Inspect-and-Adapt Alignment Cycle (Iterative-Corrective)

In cases where instances exhibit omissions or substantial discrepancies, this step involves conducting collective interviews with the involved actors to harmonize the differences. Nevertheless, all modifications to the instances are documented, drawing on the individual interviews previously conducted, in order to preserve the original perspectives of each actor.

For the sake of simplicity, throughout the remainder of this paper, we assume that there are multiple process instances, each containing the same number of functions, which have already been refined through the iterative-corrective process.

This stage resembles retrospectives and inspect-and-adapt cycles in Agile. Stakeholders collectively review discrepancies, adjust their representations, and converge toward alignment, while preserving the record of individual perspectives.

5.5. Creating a Shared Alignment Artifact Through Evidence-Supported Selection

Once the tightly and loosely coupled tuples have been identified, values are assigned to the weights of the relevant indicators (see

Table 3). The process for selecting these indicators is detailed in

Section 4.3; however, they remain open to further enrichment under the open world assumption. To ensure objectivity and adaptability, each indicator may be associated with a specific quantitative formula, which analysts can define based on the needs and characteristics of each use case.

After analysts supporting the methodology implementation assign values to the indicators for each function, the performance coefficient for each function in the tuple is calculated in close collaboration with the relevant actors and departments:

where

is the performance coefficient for the

i-th function in the tuple and

is the weight assigned by analysts to the j-th indicator.

Once all functions within the tuples have been evaluated, further interaction with the interviewed actors is required. Guided by the evidence provided by the performance coefficient, they are then asked to select one function from each tuple. In order to achieve consensus, agreement must be reached by all interviewed actors, both on which functions to select and on the completeness of the representation (e.g., granularity, missing functions, etc.). This is done in a cyclical process that continues until agreement is reached among all parties. However, as mentioned, it is not uncommon for agreement to remain elusive. In such cases, the previously described coefficient provides evidence that can assist in the function selection process. We can then define the consensus function as:

where

is the function that has the highest

within a tuple. This statement is particularly useful both when there is no consensus among the actors and when further interaction with them is no longer possible.

We define as the set of functions on which the stakeholders have reached consensus, as the set of functions on which consensus has not been reached, and as the set of all consensus functions . Hence, the SAA is defined as .

This allows us to define a simple evidence-supported selection algorithm (Algorithm 1) for cases with lack of consensus, which simply takes the function with the highest performance coefficient for each tuple (

). While in Agile practice, such fallback mechanisms are rare, in large-scale multi-stakeholder settings, they ensure that progress continues without blocking teams, thus strengthening Agile ceremonies with quantifiable evidence. This complements Agile decision-making by offering a fallback mechanism when consensus cannot be reached, ensuring continuous progress while respecting Agile’s emphasis on adaptability.

| Algorithm 1 Evidence-supported selection algorithm for shared alignment |

- 1:

procedure SelectByEvidence(T) ▹ Force the output of the SAA - 2:

- 3:

for do ▹ Cycle all tuples where consensus has not been reached - 4:

- 5:

- 6:

for do - 7:

if then - 8:

if then - 9:

- 10:

- 11:

▹ Insert the best-performing function - 12:

return ▹ The SAA

|

5.6. Shared Alignment Artifact (SAA) Extraction as a Shortest Path Problem

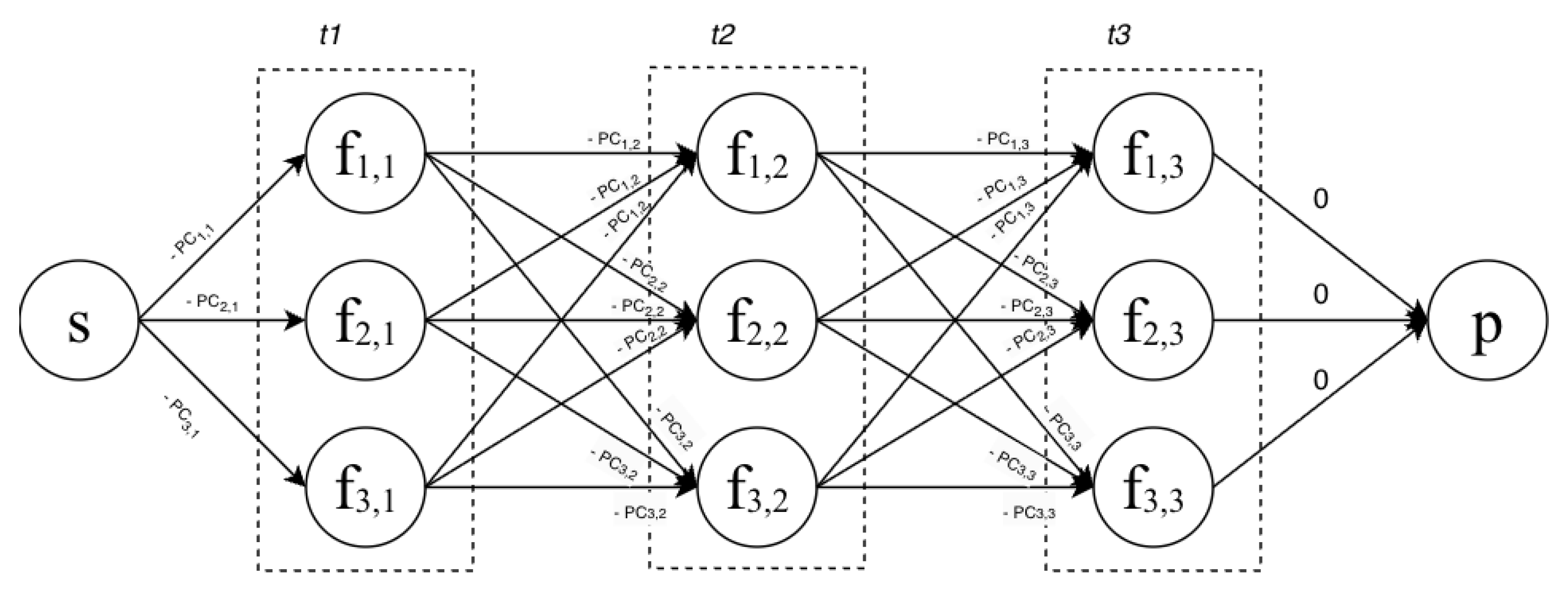

We assume that we have three process instances, each containing three functions (see

Figure 4). Furthermore, let us assume that three tuples are identified.

We can therefore introduce a node representing the starting point of the process and another node representing its end. Furthermore, to model the decision-making process, all function nodes within each tuple must be connected to all function nodes in the subsequent tuple (see

Figure 5).

Finally, the corresponding performance coefficients of each function, represented in

Figure 6 as

, are added as weights to the edges terminating in the respective function

k of the tuple

l. For the end node, zero weights are assumed.

At the current stage, the SAA obtained through evidence-supported selection is made up of the consensus functions, i.e., those that maximize the

in a specific tuple. In other terms, it is represented by the nodes, and therefore the functions, belonging to the maximum path. Consequently, by inverting the sign of all edge weights, the problem can be reformulated as a minimum path problem, thereby simplifying its mathematical treatment and resulting in the graph shown in

Figure 6.

We can therefore apply any suitable algorithm for finding the shortest path in a directed graph with negative edge weights, such as the Bellman-Ford algorithm [

41,

42]. We have thus demonstrated that it is possible to obtain a SAA using the evidence-supported selection approach, and that this yields a result in finite time. Specifically, by employing the Bellman-Ford algorithm, the computational complexity is given by:

where V is the number of nodes and E is the number of edges in the graph.

In practice, this fallback preserves flow of value when consensus cannot be reached within a cadence, aligning with Agile’s preference for non-blocking, inspect-and-adapt progress.

6. Software for Supporting the Shared Alignment Artifact

6.1. Architecture

We implemented the procedure described in

Section 5 to validate its feasibility.

Figure 7 describes the developed distributed architecture.

In addition to the clear advantages of availability and scalability, a containerized architecture using the REST principles also allows, as a side effect, the exposure of all the knowledge accumulated in the ontology external service (see below), along with the various case studies, even outside the application (potentially creating economic value as well). The same can be said for the natural language recognition model’s external services, which can be both trained and utilized by external sources, creating a positive feedback loop.

Presentation Layer. It features a graphical interface that adapts to the user’s device, enabling users to manipulate data and extract information from FRAM process instances using their credentials. The presentation layer does not handle data directly; instead, it forwards information to the business layer, where all logic is processed.

Business Logic. It is responsible for processing all requests and contacting the appropriate layers to fulfill them. Regarding security, it interacts with the data layer to associate each request with a user’s identity and, if necessary, to create, modify, or revoke credentials. In the case of data manipulation, it collaborates with the data layer and external NLP and/or ontology services (if needed) and stores the results of these operations back in the data layer.

Data Layer. It contains a comprehensive list of all information that must be stored beyond the application’s lifecycle, such as projects, instances, users, and more. If data manipulation is required, the request is forwarded to the business layer, which performs the necessary operations and returns the result to be stored back in the entity database. Regarding security, this layer is responsible for securely storing user credentials using strong hashing algorithms and issuing corresponding tokens, which users use to make their requests. Finally, the layer is tasked with promptly validating the tokens in the requests forwarded to the business layer.

Ontology and NLP External Services. It is responsible for creating knowledge based on case studies related to the projects generated by the application, as well as developing a natural language recognition model used to pair functions based on semantic meaning affinity.

The tool is intended to be used alongside existing Agile tooling and ceremonies: the SAA can inform backlog refinement and planning (e.g., by translating agreed functions into backlog items and acceptance criteria) and provides traceable, cross-stakeholder evidence that supports reviews and retrospectives without constraining team-level autonomy.

6.2. Implementation

The presentation layer (see

Figure 7) is used by the user to interact with the application. This layer is built using React [

43], a popular front-end development framework, and hosted on Railway [

44], an application hosting service. The business logic layer encompasses all the logic required to access, manipulate, and return data to the presentation layer. If necessary, it can also communicate with other containers to perform operations. This layer consists of an Express [

45] middleware, built with Node.js and hosted on Railway as well. For the data layer, Firebase [

46] was selected due to its integration of several services, including a non-relational tree database. This data structure facilitates document manipulation and offers a minimal transition to the JSON [

47] notation, which is highly used as payload in the HTTP/S [

48] protocol. Firebase also supports user, role, and password management (including secure hashing strategies) and, most importantly, handles JWT [

49] tokens to ensure secure communication between the presentation layer and the rest of the application.

6.3. Software Application

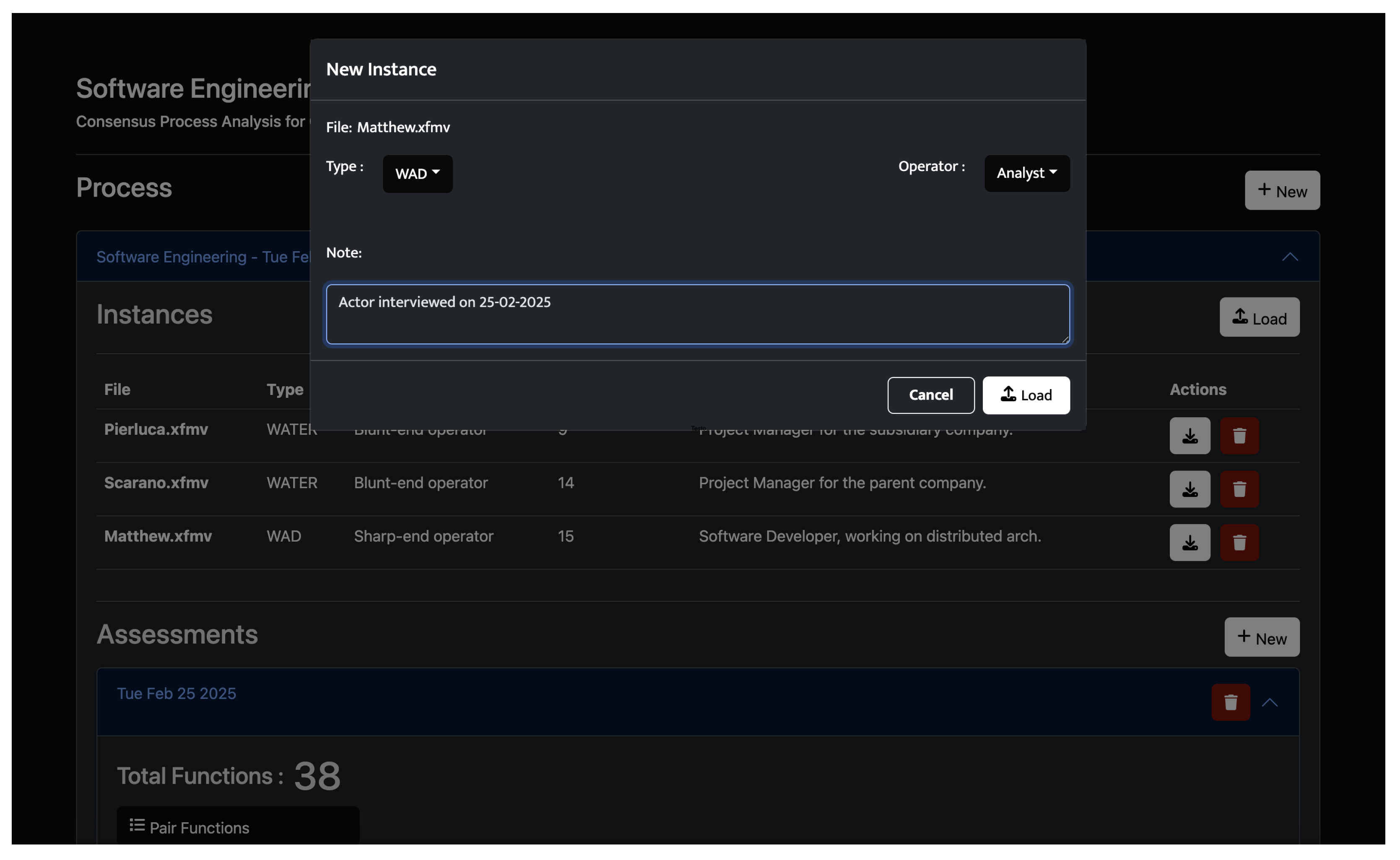

The developed software is a web application that runs within a browser. A user logs in using the provided credentials and remains authenticated as long as the associated token remains valid. After logging in, the user selects one of the projects tied to an organization, which includes the individual processes being examined. Each process is made up of a series of instances, each linked to a FRAM file. Actor type information and, potentially, generic notes are then added to each instance. Hence, for each project, it is possible to analyze multiple processes of an organization under examination, and for each process, load the related instances associated with the interviewed actors, labeling them with the corresponding WAx entities. Once the instances are obtained, they can be assessed, allowing the user to manage the entire procedure required to achieve consensus. This involves first generating tightly coupled tuples and modifying them if necessary, manually validating loosely coupled tuples, and associating the relevant identifiers. After completing this procedure, the user can select and edit any function chosen from the tuples, or optionally, apply the evidence-supported selection algorithm to extract the SAA.

Once all instances have been uploaded (see

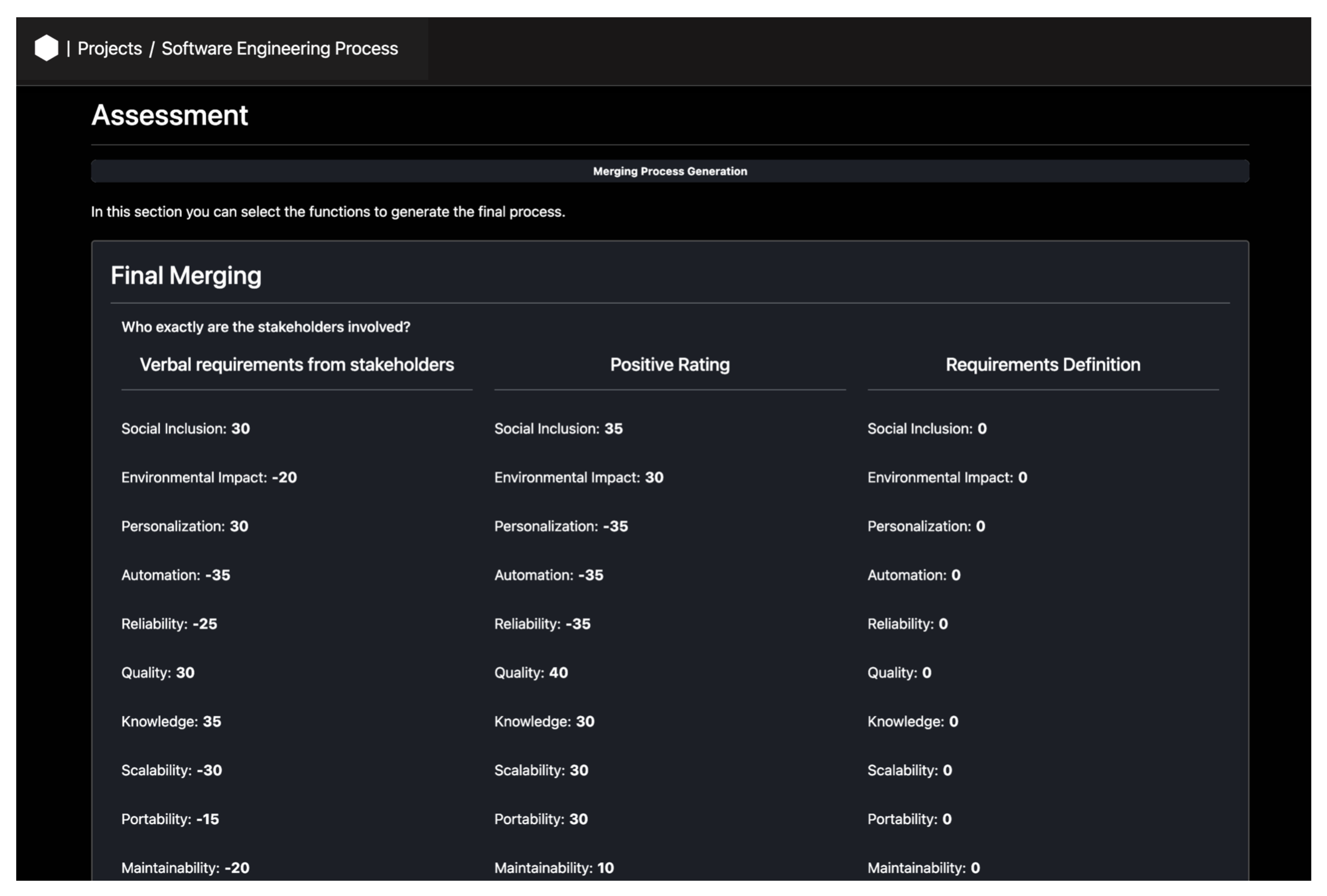

Figure 8), the user can proceed with the assessment. Initially, tightly coupled tuples are generated, which the user can modify as necessary. It is important to note that the business rules in the appropriate layer dictate that whenever a new instance is loaded, all previously created assessment reports are deleted. This is necessary because those assessment reports would contain values that no longer align with the updated number of instances, especially concerning the tuples and resulting SAAs. After all necessary instances have been loaded and the tightly coupled tuples formed, the focus shifts to reviewing the loosely coupled tuples, which are subject to further comparison. For each function within the tuple, a weight is assigned to each relevant indicator, if applicable, in collaboration with various departments within the company, such as business, risk, legal, and sustainability. For instance,

Figure 9 displays a screenshot of the interface used to assign weights to functions such as

verbal requirements from stakeholders or

positive rating. Specifically, indicator values are set by adjusting sliders along corresponding bars. To enhance visual clarity, the indicator labels have been replaced with icons in the figure; however, the labels remain accessible by hovering the mouse cursor over each icon.

A guiding question, for example, “who exactly are the stakeholders involved in this project?”, is assigned to each tuple, as illustrated in

Table 2. This step helps different actors, even those from diverse professional backgrounds, converge toward a shared choice that considers the subtle distinctions captured in the related functions across instances. The final step involves selecting each consensus function from the tuples, with input from the actors, as shown in

Figure 10. Once all selections are made, the application generates and exports a table, which represents the finalized SAA.

If consensus cannot be reached among stakeholders through direct interaction, the user can apply the evidence-supported selection algorithm to extract the SAA. This algorithm operates by automatically selecting, for each tuple of related functions where consensus has not been achieved, the function with the highest performance coefficient (

). Specifically, the algorithm iterates over all such tuples, evaluates the

for each candidate function, and selects the one with the maximum value. In this way, the SAA is completed by combining all functions agreed upon by the stakeholders with those selected by the evidence-supported method, ensuring that a consistent process can be generated even in the absence of full consensus. The pseudocode for this algorithm is provided in

Section 5.5 (Algorithm 1), and further details regarding its application are discussed there. This approach is intended as a fallback mechanism to be used when reaching consensus through stakeholder engagement is not possible.

7. Experimentation and Validation

As described in the case study section (see

Section 2), to validate the methodology and the software application, two reference managers and a developer were chosen, one in the parent company and two in the subsidiary (see

Table 4).

Then, the FRAM process instances were modeled starting from the individual related interviews.

Table 5 shows the analysis and implementation phases of the software engineering process from the perspective of the IT-PM working in the parent company.

After creating the tightly coupled tuples, we reorganized and validated the loosely coupled tuples and prepared the corresponding questions for the interview round.

Table 1 presents an example of a tightly coupled tuple. All the three functions share an almost identical meaning. The column “FRAM upstream function aspects” in

Table 1 indicates the types of connections, excluding input and output, that each function has with other functions in the original process instances. In the case presented in

Table 1, none is present. Therefore, since they share both the same meaning and the same FRAM preconditions, they indeed represent a tightly coupled tuple. Moreover, with regard to the synthesis of the SAA, exactly one of these functions, regardless of which, will necessarily be included.

Table 2, instead, includes an example of a loosely coupled tuple. The tuple in

Table 2 contains functions that, at first glance, appear to have a similar meaning. However, one of them is connected to another function in its respective instance through a “precondition” relationship. Consequently, we cannot assert that all three have the same meaning with sufficient confidence. Therefore, this is an example of a loosely coupled tuple.

As mentioned, at this stage, instances that exhibit significant deviations from the others are identified, and all stakeholders are subsequently engaged in a collective discussion to address and resolve any discrepancies. In the present case, no substantial discrepancies were observed among the instances produced by the stakeholders. Accordingly, we proceeded to the next phase.

This step is to assess the

for each function in the tuple. Below, we present an example concerning the previous tuple in

Table 2, omitting, for the sake of simplicity, the single values of each indicator.

Table 2 provides valuable insights into the various aspects of the proposed methodology’s operation. Take, for example, the first function (i.e., BU requirement definition), which implies that the drafting of the requirements is the responsibility of a different department from the one that will later go on to implement the product. We have a positive contribution on the performance coefficient given by the various indicators of the quality of the software (COCOMO II) and a negative contribution given by the costs and (human) resources of the business unit to produce the documentation. The second (i.e., drafting requirements), on the other hand, does not specify who is going to produce the requirements of the product, suggesting that the same group that is going to implement it will, thus leading to an increase in the time required and a decrease of quality of the product, as well as a lengthening of the validation process. The third (i.e., verbal requirements from stakeholders), finally, states that the requirements are merely “verbal” and involve multiple stakeholders (and therefore not just one department). All these variables determine not only a different PC, but clear aspects that must be conveyed to the actors in the process for the choice of the function that will then be added to the SAA.

The performance coefficients in

Table 2 reflect the overall evaluation of each function based on a combination of relevant indicators, such as quality, efficiency, cost, and resource requirements. A higher performance coefficient indicates a function that is considered more favorable according to these metrics, while a lower or negative coefficient highlights functions with less desirable characteristics. These values help guide the selection of the most appropriate function for inclusion in the SAA, especially when consensus among stakeholders has not been reached.

The process was then iterated for all the loosely coupled tuples, computing the

for each tuple and formulating a relevant question to be submitted to the stakeholders during the collective interviews. In the specific case under examination, we interacted with all stakeholders until the end, resulting in the SAA obtained through consensual synthesis, as shown in

Table 6 where the header “Connected to (FRAM Connection Type)” represents which numbered function the current function is connected to and what type the connection is. For instance, 2(Input) means that a function is linked to the function number 2 with an Input-type relationship.

As mentioned earlier, the questions are those that clarify all the facets of a function in the process (beyond the numerical value of the ) and, thus, guide all the actors toward the best function to choose. Counterintuitively, this function can sometimes incur the highest performance cost. Therefore, it is clear that, when possible, it is always preferable to engage in discussions with the actors rather than forcing the SAA. The final consideration highlights a unique aspect of the software development process within this organization. Operating in the legalized gaming sector, the organization is required to submit its solutions first to certifying bodies and, subsequently, to the State Customs and Monopolies Agency.

Table 6 provides a concrete example of the Shared Alignment Artifact generated by the methodology. The table presents the synthesized sequence of functions selected from each tuple, either through stakeholder consensus or, when consensus was not possible, through the evidence-supported selection mechanism. Each row also reports the FRAM connections preserved in the final model. Together, these elements illustrate how divergent stakeholder perspectives are consolidated into a unified and operational process representation.

The main difference between the SAA obtained through consensual synthesis and the one derived from the evidence-supported selection algorithm lies exclusively in the first function (see

Table 7). The others have been omitted for simplicity, as they are identical in both outputs.

In the case study, the SAA was reviewed on a cadence aligned with team ceremonies: key decisions from the SAA informed upcoming backlog refinement and sprint planning; open misalignments were carried as explicit risks to be revisited in joint retrospectives. This cadence preserved flow for teams while preventing cross-organizational issues from remaining tacit.

8. Discussion

The proposed methodology offers several advantages when applied in complex Agile-at-scale environments. First, it provides a structured mechanism for capturing diverse stakeholder perspectives, including both Work-as-Imagined and Work-as-Done representations, which are often misaligned in real organizations. This is a notable improvement over traditional Agile ceremonies, which typically operate at the team level and do not systematically address cross-organizational divergence. Second, by integrating FRAM and WAx with quantifiable performance indicators, the methodology introduces an evidence-supported decision framework that helps stakeholders converge on a Shared Alignment Artifact even when consensus is difficult to achieve. The ability to fall back on a measurable performance coefficient, supported by Algorithm 1, ensures continuity of decision-making, strengthening the alignment process in contexts where subjective agreement alone is insufficient. Third, the accompanying software tool provides an operational environment that automates pairing of functions, assessment of tuples, and extraction of the SAA, making the methodology practically deployable in real industrial settings.

However, despite these strengths, the study also presents certain limitations. The validation step in

Section 7 is not based on quantitative experiments. Instead, the methodology was tested in a real industrial context involving practitioners from both a parent company and one of its subsidiaries in the regulated gaming domain. This ensured practical validity and allowed us to assess the methodology under realistic organizational constraints and workflow dynamics. Yet, repeating the same evaluation across multiple organizations would require substantial time, coordination efforts, and financial resources, due to the need for extensive stakeholder interviews, FRAM modeling sessions, and iterative alignment rounds. For this reason, additional large-scale or repeated experiments were not feasible within the scope of this study.

We acknowledge this as a limitation of the work. Although the case study provides strong qualitative evidence of feasibility and usefulness, a broader set of empirical validations, either quantitative or across multiple organizations, would strengthen the generalizability of the results. As part of future work, we intend to conduct additional case studies in different sectors or organizational configurations. These will allow us to refine the performance indicators, and further assess the scalability of the methodology. Such studies will be reported in future publications, as conducting them at this stage would have significantly increased the duration and cost of the research.

9. Conclusions

The software development process is now nearly ubiquitous across all organizations. As discussed, several challenges arise, primarily due to the differing objectives of the various stakeholders involved and the diverse perspectives they bring to the process. To address this, we have developed a methodology and a set of tools, including software, to extract a SAA that synthesizes the best aspects of all the instances contributed by different actors. This creates value for the organization that goes beyond the mere quality or performance of the software. It also delivers a quantifiable degree of stakeholder satisfaction, as reflected in the ability to establish a guided process that integrates all their goals and desires. This new process is therefore inherently better than any generic model or process because it is not based on the specific characteristics of organizations but customized to the stakeholders’ needs.

While our methodology is inspired by and builds upon the strengths of existing frameworks such as FRAM and WAx, its originality lies in the way these are integrated and extended to address the challenge of achieving stakeholder consensus, resulting in a practical and adaptable approach that, to our knowledge, has not previously been presented in the field of software process modeling.

This synthesis of the various instances opens up unprecedented possibilities, such as the ability to compare the current state of the process with the requirements outlined by regulation (WAN) [

5] and measure, through allostatic load [

31], the extent of any deviation.

The proposed methodology can also be applied to other process models, even beyond FRAM, as long as they are made up of functions. This is achieved by maintaining the concept of the tuple.

By enriching the set of indicators, the proposed methodology can be applied to processes concerning other systems beyond software engineering, integrating metrics from other evaluation models such as, for example, the COSYSMO [

50].

In conclusion, the SAA is an extension to Agile-at-scale ways of working: it preserves team autonomy while adding an evidence-supported mechanism for alignment across organizational and regulatory boundaries. This positions the approach as a complementary enhancement, useful precisely where standard ceremonies alone cannot guarantee cross-stakeholder convergence.