A Scoping Review of How High-Income Country HIV Guidelines Define, Assess, and Address Oral ART Adherence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Timeframe

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Information Sources

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.6. Data Selection

2.7. Data Charting

2.8. Synthesis of Data

3. Results

3.1. The Literature Search

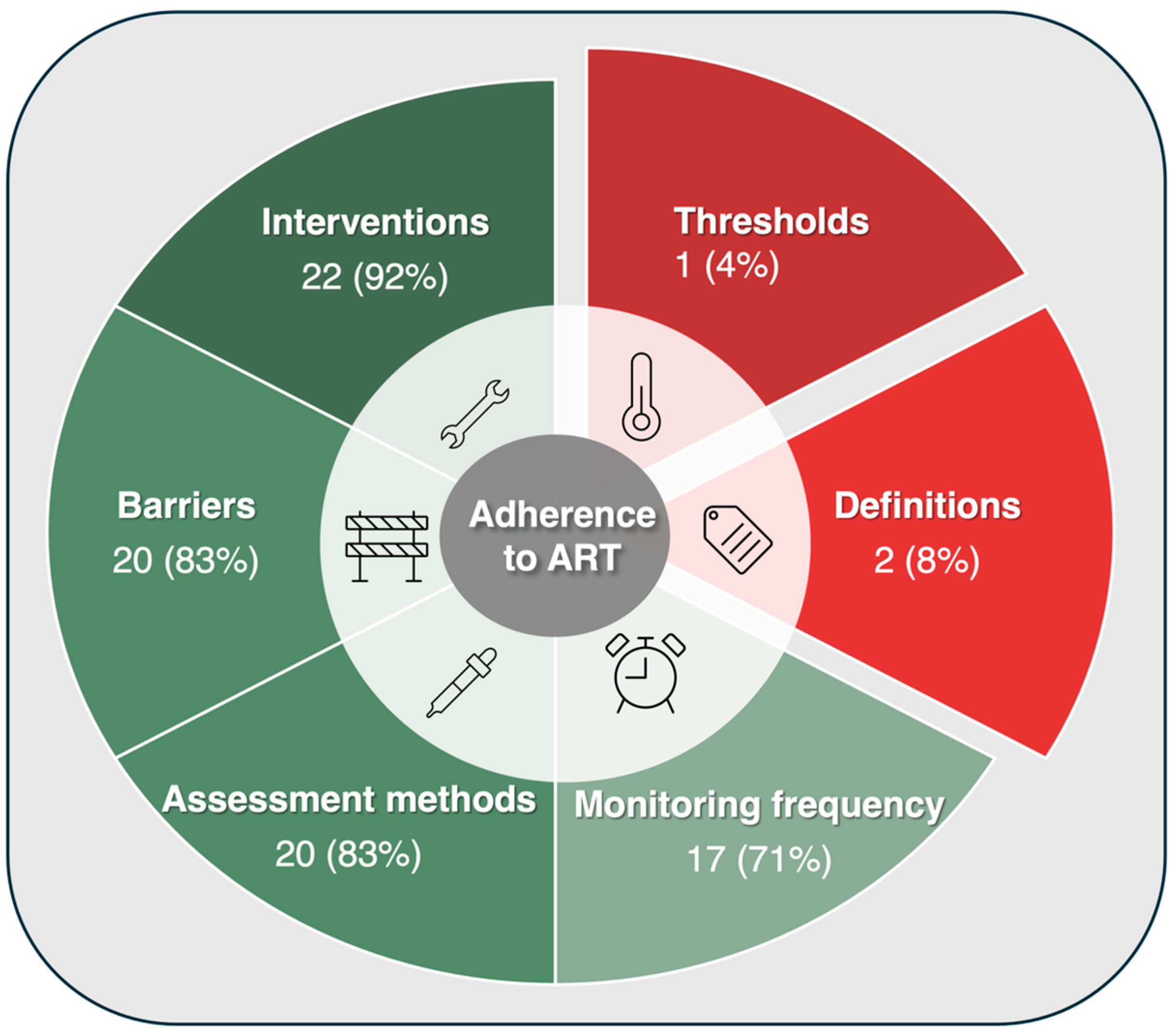

3.2. The Synthesis

3.3. Definitions of Adherence: A Rarity Across Guidelines

3.4. Thresholds of Adherence: Missing in Action

3.5. Interventions for Improving Adherence: Almost Always Present, Yet Extremely Varied

3.5.1. Enhance Knowledge and Skills

3.5.2. Optimize Treatment or Care

3.5.3. Support Psychosocial or Daily Needs

3.5.4. Promote Adherence Behaviors

3.5.5. Tailored, Multidisciplinary Approaches

3.6. Barriers to Taking ART: A Spectrum Across Guidelines

3.6.1. Lifestyle Factors

3.6.2. Cognitive and Emotional Aspects

3.6.3. Characteristics of ART

3.6.4. Healthcare Services and Systems

3.6.5. Health Experience and State

3.6.6. Social and Material Context

3.7. Methods for Assessing Adherence: Common, Yet Unstandardized

3.7.1. Clinical Evaluation

3.7.2. Lab-Based Monitoring

3.7.3. Medication Supply and Monitoring Tools

3.8. Frequency and Timing for Assessing Adherence: Context-Driven and Varied

3.8.1. Routine or Scheduled Monitoring

3.8.2. Context-Driven Monitoring

4. Discussion

4.1. A Lack of Definitions for ART Adherence and Its Thresholds

4.2. A Great Variety of Interventions Recommended

4.3. Reported Barriers to Adherence: Consistent with the Literature

4.4. A Diversity of Methods and Frequencies for Assessing Adherence

4.5. A Need for a Consensus in Addressing Adherence

4.6. Considerations of Novel Assessment Tools for Future Guidelines

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vrijens, B.; De Geest, S.; Hughes, D.A.; Przemyslaw, K.; Demonceau, J.; Ruppar, T.; Dobbels, F.; Fargher, E.; Morrison, V.; Lewek, P.; et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 73, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.B.; Sackett, D.L.; Gibson, E.S.; Taylor, D.W.; Hackett, B.C.; Roberts, R.S.; Johnson, A.L. Improvement of medication compliance in uncontrolled hypertension. Lancet 1976, 1, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Mancilla, J.R.; Haberer, J.E. Adherence Measurements in HIV: New Advancements in Pharmacologic Methods and Real-Time Monitoring. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018, 15, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabhe, W.M.; Chalmers, L.; Bereznicki, L.R.; Peterson, G.M. Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy and Virologic Failure: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2016, 95, e3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, R.N.; Kluisza, L.; Nguyen, N.; Dolezal, C.; Leu, C.S.; Wiznia, A.; Abrams, E.J.; Anderson, P.L.; Castillo-Mancilla, J.R.; Mellins, C.A. Measuring ART Adherence Among Young Adults with Perinatally Acquired HIV: Comparison Between Self-report, Telephone-Based Pill Count, and Objective Pharmacologic Measures. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 3927–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. 2023. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/whats-new (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Nachega, J.B.; Hislop, M.; Dowdy, D.W.; Lo, M.; Omer, S.B.; Regensberg, L.; Chaisson, R.E.; Maartens, G. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy assessed by pharmacy claims predicts survival in HIV-infected South African adults. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006, 43, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Gerver, S.M.; Fidler, S.; Ward, H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adolescents living with HIV: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2014, 28, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, E.J.; Nachega, J.B.; Buchan, I.; Orbinski, J.; Attaran, A.; Singh, S.; Rachlis, B.; Wu, P.; Cooper, C.; Thabane, L.; et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2006, 296, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Moore, R.D.; Graham, N.M. Potential factors affecting adherence with HIV therapy. AIDS 1997, 11, 1665–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange (CATIE). The Epidemiology of HIV in Canada. Available online: https://www.catie.ca/the-epidemiology-of-hiv-in-canada (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Deering, K.N.; Chong, L.; Duff, P.; Gurney, L.; Magagula, P.; Wiedmeyer, M.L.; Chettiar, J.; Braschel, M.; D’Souza, K.; Shannon, K. Social and Structural Barriers to Primary Care Access Among Women Living with HIV in Metro Vancouver, Canada: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2021, 32, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golin, C.E.; Liu, H.; Hays, R.D.; Miller, L.G.; Beck, C.K.; Ickovics, J.; Kaplan, A.H.; Wenger, N.S. A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2002, 17, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Petrozzino, J.J. An evidence-based review of treatment-related determinants of patients’ nonadherence to HIV medications. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009, 23, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsberg, D.R.; Hecht, F.M.; Charlebois, E.D.; Zolopa, A.R.; Holodniy, M.; Sheiner, L.; Bamberger, J.D.; Chesney, M.A.; Moss, A. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS 2000, 14, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altice, F.; Evuarherhe, O.; Shina, S.; Carter, G.; Beaubrun, A.C. Adherence to HIV treatment regimens: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyachati, K.H.; Ogbuoji, O.; Price, M.; Suthar, A.B.; Negussie, E.K.; Barnighausen, T. Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A rapid systematic review. AIDS 2014, 28 (Suppl. S2), S187–S204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 427–432, discussion 433–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekelle, P.G.; Ortiz, E.; Rhodes, S.; Morton, S.C.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Woolf, S.H. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical practice guidelines: How quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA 2001, 286, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote 20; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA. PRISMA Flow Diagram. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-flow-diagram (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- NVivo 14; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Doncaster, Australia, 2020.

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, K.; Vicente, S.; Mate, K.K.V.; Lessard, D.; Ahmed, S.; Lebouche, B. Content validation of a new measure of patient-reported barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence, the I-Score: Results from a Delphi study. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2022, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lindgren, B.M.; Lundman, B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 56, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Committee for Drug Evaluation and Therapy. British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS (BC-CfE). Therapeutic Guidelines for Antiretroviral (ARV) Treatment of Adult HIV Infection. 2020. Available online: https://bccfe.ca/bccfe-documents/therapeutic-guidelines-for-antiretroviral-arv-treatment-of-adult-hiv-infection/ (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Ontario Clinical Care Guidelines. Clinical Care Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. Available online: https://occguidelines.com/guidelines/ (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Gouvernement du Québec. La Thérapie Antirétrovirale Pour les Adultes Infectés par le VIH. 2021. Available online: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2021/21-337-02W.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Mokrane, S.; Dekker, N.; Van Royen, P.; Martin, C.; Van Beckhoven, D.; Swannet, S.; Florence, E.; Koeck, R.; Cornelissen, T.; De Coninck, L.; et al. GPC sur la Prise en Charge des Patients Vivant Avec le VIH. 2022. Available online: https://www.worel.be/DynamicContent/DownloadFile?url=eqvrbsjay31he1nxpl3uryyfzeqs0gbkd22mz03pz1b1.pdf&filename=GPC_VIH_Full_text_FR_202304.pdf&openInBrowser=false (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- European AIDS Clinical Society. EACS Guidelines Version 11.1; European AIDS Clinical Society: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/eacs-guidelines/ (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Conseil National du Sida et des Hépatites Virales et Agence Nationale de la Recherche. Initiation d’un Premier Traitement Antirétroviral. 2018. Available online: https://cns.sante.fr/sites/cns-sante/files/2017/01/experts-vih_initiation.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Conseil National du Sida et des Hépatites Virales et Agence Nationale de la Recherche. Prise en Charge des Comorbidités au cours de l’Infection par le VIH. 2019. Available online: https://cns.sante.fr/sites/cns-sante/files/2019/08/experts-vih_comorbidites.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Conseil National du Sida et des Hépatites Virales et Agence Nationale de la Recherche. Suivi de l’Adulte Vivant Avec le VIH et Organisation des Soins. 2018. Available online: https://cns.sante.fr/sites/cns-sante/files/2018/05/experts-vih_suivi.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- The Korean Society for AIDS. The 2018 Clinical Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of HIV/AIDS in HIV-Infected Koreans. Infect. Chemother. 2019, 51, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, J.; Carlander, C.; Albert, J.; Flamholc, L.; Gisslén, M.; Navér, L.; Svedhem, V.; Yilmaz, A.; Sönnerborg, A. Antiretroviral treatment for HIV infection: Swedish recommendations 2019. Infect. Dis. 2019, 52, 295–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British HIV Association. BHIVA guidelines on antiretroviral treatment for adults living with HIV-1 2022. HIV Med. 2022, 23, 3–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British HIV Association. British HIV Association Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Pregnancy and Postpartum 2018 (2019 Second Interim Update); British HIV Association: Hertfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, I.; Cromarty, B.; Deayton, J.; Dhairyawan, R.; Kidd, M.; Taylor, C.; Thornhill, J.; Tickell-Painter, M.; van Halsema, C. British HIV Association guidelines for the management of HIV-2 2021. HIV Med. 2021, 22 (Suppl. S4), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, R.T.; Bedimo, R.; Hoy, J.F.; Landovitz, R.J.; Smith, D.M.; Eaton, E.F.; Lehmann, C.; Springer, S.A.; Sax, P.E.; Thompson, M.A.; et al. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults 2022 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA Panel. Jama Spec. Commun. 2022, 329, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-arv/whats-new (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Thompson, M.A.; Horberg, M.A.; Agwu, A.L.; Colasanti, J.A.; Jain, M.K.; Short, W.R.; Singh, T.; Aberg, J.A. Primary Care Guidance for Persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: 2020 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e3572–e3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. 2023. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/perinatal/whats-new (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Testing, Treatment, Service Delivery and Monitoring: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and STI Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on Person-Centred HIV Patient Monitoring and Case Surveillance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Consolidated HIV Strategic Information Guidelines: Driving Impact Through Programme Monitoring and Management; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Update of Recommendations on First- and Second-Line Antiretroviral Regimens; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Updated Recommendations on Service Delivery for the Treatment and Care of People Living with HIV; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, S.; Kavookjian, J. Motivational interviewing as a behavioral intervention to increase HAART adherence in patients who are HIV-positive: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS Care 2012, 24, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathes, T.; Pieper, D.; Antoine, S.L.; Eikermann, M. Adherence-enhancing interventions for highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients—A systematic review. HIV Med. 2013, 14, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.A.; Roy, A.; Burrell, A.; Fairchild, C.J.; Fuldeore, M.J.; Ollendorf, D.A.; Wong, P.K. Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008, 11, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breather Trial Group. Weekends-off efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children, adolescents, and young adults (BREATHER): A randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet HIV 2016, 3, e421–e430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, R.; de Truchis, P.; Assoumou, L.; Lambert, S.; Bellet, J.; Amat, K.; Lefebvre, B.; Allavena, C.; Katlama, C.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; et al. A 4-days-on and 3-days-off maintenance treatment strategy for adults with HIV-1 (ANRS 170 QUATUOR): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, parallel, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e79–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauceda, J.A.; Neilands, T.B.; Johnson, M.O.; Saberi, P. An update on the Barriers to Adherence and a Definition of Self-Report Non-adherence Given Advancements in Antiretroviral Therapy (ART). AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genberg, B.L.; Wilson, I.B.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Arnsten, J.; Goggin, K.; Remien, R.H.; Simoni, J.; Gross, R.; Reynolds, N.; Rosen, M.; et al. Patterns of antiretroviral therapy adherence and impact on HIV RNA among patients in North America. AIDS 2012, 26, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcellin, F.; Spire, B.; Carrieri, M.P.; Roux, P. Assessing adherence to antiretroviral therapy in randomized HIV clinical trials: A review of currently used methods. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2013, 11, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, P.E.; Thompson, M.A.; Saag, M.S.; IAS-USA Treatment Guidelines Panel. Updated Treatment Recommendation on Use of Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine for People with HIV from the IAS-USA Guidelines Panel. JAMA 2024, 331, 1060–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwlaat, R.; Wilczynski, N.; Navarro, T.; Hobson, N.; Jeffery, R.; Keepanasseril, A.; Agoritsas, T.; Mistry, N.; Iorio, A.; Jack, S.; et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD000011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassavou, A.; Sutton, S. Automated telecommunication interventions to promote adherence to cardio-metabolic medications: Meta-analysis of effectiveness and meta-regression of behaviour change techniques. Health Psychol. Rev. 2018, 12, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. State of the science: The efficacy of a multicomponent intervention for ART adherence among people living with HIV. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2014, 25, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubber, Z.; Mills, E.J.; Nachega, J.B.; Vreeman, R.; Freitas, M.; Bock, P.; Nsanzimana, S.; Penazzato, M.; Appolo, T.; Doherty, M.; et al. Patient-Reported Barriers to Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langebeek, N.; Gisolf, E.H.; Reiss, P.; Vervoort, S.C.; Hafsteinsdottir, T.B.; Richter, C.; Sprangers, M.A.; Nieuwkerk, P.T. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: A meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsberg, D.R.; Hecht, F.M.; Clague, H.; Charlebois, E.D.; Ciccarone, D.; Chesney, M.; Moss, A. Provider assessment of adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2001, 26, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericksen, R.; Crane, P.K.; Tufano, J.; Ralston, J.; Schmidt, S.; Brown, T.; Layman, D.; Harrington, R.D.; Dhanireddy, S.; Stone, T.; et al. Integrating a web-based, patient-administered assessment into primary care for HIV-infected adults. J. AIDS HIV Res. 2012, 4, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Villanueva, G.; Probyn, K.; Sguassero, Y.; Ford, N.; Orrell, C.; Cohen, K.; Chaplin, M.; Leeflang, M.M.; Hine, P. Accuracy of measures for antiretroviral adherence in people living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 7, CD013080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, N.; Bader, L.R. Consensus development methods: Considerations for national and global frameworks and policy development. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 2222–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Schuster, T.; Engler, K.; Vicente, S.; Lessard, D.; Routy, J.P.; Kronfli, N.; Cox, J.; de Pokomandy, A.; Lebouché, B. Exploring the link between sociodemographic factors and barriers to adherence: Survey data collected from people with HIV. In Proceedings of the 52nd North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) Annual Meeting, Québec City, QC, Canada, 20–24 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Acin, P.; Luque, S.; Subirana, I.; Vila, J.; Fernandez-Sala, X.; Guelar, A.; Antonio-Cusco, M.; Arrieta, I.; Knobel, H. Development and Validation of a Risk Score for Predicting Non-Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2023, 39, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo-Verdugo, R.; Polo, R.; Knobel, H. Consensus document on enhancing medication adherence in patients with the human immunodeficiency virus receiving antiretroviral therapy. Farm. Hosp. 2020, 44, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Number | Terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | exp HIV/or exp Anti-Retroviral Agents/or exp HIV Infections/or Antiretroviral Therapy, Highly Active/ |

| 2 | ((immun* deficien* or immun?deficien*) adj3 (virus* or syndrome)).tw,kf. |

| 3 | HIV*.tw,kf. |

| 4 | (aids adj5 (virus* or viral or retrovirus or lentivirus or infection* or syndrome*)).tw,kf. |

| 5 | (anti-retroviral or antiretroviral).tw,kf. |

| 6 | (“nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor*” or NRTI* or abacavir or emtricitabine or ziagen or emtriva or iamivudine or epivir or tenofovir or viread or zidovudine or retrovir or “azidothymidine non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor*” or NNRTI* or doravirine or pifeltro or efavirenz or sustiva or etravirine or intelence or nevirapine or viramune or rilpivirine or edurant or protease inhibitor* or PIs or atazanavir or reyataz or darunavir or prezista or fosamprenavir or lexiva or ritonavir or norvir or tipranavir or aptivus or fusion inhibitors enfuvirtide or fuzeon or CCR5 antagonist* or maraviroc or selzentry or “integrase strand transfer inhibitor*” or INSTI* or cabotegravir or vocabria or dolutegravir or tivicay or raltegravir or isentress or attachment inhibitor* or fostemsavir or rukobia or post-attachment inhibitor* or ibalizumab-uiyk or trogarzo or pharmacokinetic enhancer* or cobicistat or tybost).tw,kf. |

| 7 | (epzicom or dolutegravir or triumeq or trizvir or cobicistat or evotaz or bictegravir or alafenamide or biktarvy or rilpivirine or cabenuva or prezcobix or symtuza or juluca or disoproxil or delstrigo or atripla or symfi or elvitegravir or genvoya or stribild or odefsey or complera or descovy or truvada or cimduo or combivir or lopinavir or ritonavir or kaletra).tw,kf. |

| 8 | (atripla or apo-efavirenz or mylan-efavirenz or teva-efavirenz or dovato or lamivudine or apo-lamivudine or auro-lamivudine teva-lamivudine or kivexa or apo-abacavir or auro-abacavir or teva-abacavir or apo-emtricitabine or mylan-emtricitabine or apo-darunavir or auro-darunavir or mylan-atazanavir or teva-atazanavir celsentri or 3TC or apo-zidovudine or apo-tenofovir or auro-tenofovir or mylan-tenofovir or teva-tenofovir or apo-abacavir or mint-abacavir auro-efavirenz or mylan-efavirenz or teva-efavirenz or auro-nevirapine).tw,kf. |

| 9 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 |

| 10 | exp “treatment adherence and compliance”/ |

| 11 | ((treatment or therap* or patient* or medication* or drug*) adj2 (adhere* or compliance or comply or accept* or refus* or non-adher* or non-compliance or noncompliance or nonadhere* or persist* or cooperat*)).tw,kf. |

| 12 | 10 or 11 |

| 13 | 9 and 12 |

| 14 | exp clinical pathway/or exp clinical protocol/or clinical protocols/or exp consensus/or exp consensus development conference/or exp consensus development conferences as topic/or critical pathways/or exp guideline/or guidelines as topic/or exp practice guideline/or practice guidelines as topic/or health planning guidelines/or exp treatment guidelines/or Clinical Decision Rules/ |

| 15 | (guideline or practice guideline or consensus development conference or consensus development conference, NIH).pt. |

| 16 | (position statement* or policy statement* or practice parameter* or best practice*).ti,ab,kf. |

| 17 | (standards or guideline or guidelines).ti,kf. |

| 18 | ((practice or treatment* or clinical) adj guideline*).ab. |

| 19 | (CPG or CPGs).ti. |

| 20 | consensus*.ti,kf. |

| 21 | consensus*.ab./freq = 2 |

| 22 | ((critical or clinical or practice) adj2 (path or paths or pathway or pathways or protocol*)).ti,ab,kf. |

| 23 | recommendat*.ti,kf. or guideline recommendation*.ab. |

| 24 | (care adj2 (standard or path or paths or pathway or pathways or map or maps or plan or plans)).ti,ab,kf. |

| 25 | (algorithm* adj2 (screening or examination or test or tested or testing or assessment* or diagnosis or diagnoses or diagnosed or diagnosing)).ti,ab,kf. |

| 26 | (algorithm* adj2 (pharmacotherap* or chemotherap* or chemotreatment* or therap* or treatment* or intervention*)).ti,ab,kf. |

| 27 | (guideline* or standards or consensus* or recommendat*).au. |

| 28 | (guideline* or standards or consensus* or recommendat*).ca. |

| 29 | or/14–28 |

| 30 | 13 and 29 |

| Title | Author (Abbreviated Citation) | Origin | Year of Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Guidelines for Antiretroviral (ARV) Treatment of Adult HIV Infection [29] | The Committee for Drug Evaluation and Therapy, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS (BC, 2020) | British Columbia, Canada | 2020 |

| Clinical Care Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV in Ontario, Canada [30] | Ontario Clinical Care Guidelines (ON) | Ontario, Canada | N/A |

| La thérapie antirétrovirale pour les adultes infectés par le VIH [31] | Gouvernement du Québec (QC, 2021) | Québec, Canada | 2021 |

| GPC sur la prise en charge des patients vivant avec le VIH [32] | Mokrane S., et al. (Bel, 2022) | Belgium | 2022 |

| EACS Guidelines version 11.1, October 2022 [33] | European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) (EACS, 2022) | Europe | 2022 |

| Initiation d’un premier traitement antirétroviral [34] | Conseil national du sida et des hépatites virales et Agence nationale de la recherche (Fr, 2018a) | France | 2018 |

| Prise en charge des comorbidités au cours de l’infection par le VIH [35] | Conseil national du sida et des hépatites virales et Agence nationale de la recherche (Fr, 2019) | France | 2019 |

| Suivi de l’adulte vivant avec le VIH et organisation des soins [36] | Conseil national du sida et des hépatites virales et Agence nationale de la recherche (Fr, 2018b) | France | 2018 |

| The 2018 Clinical Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of HIV/AIDS in HIV-Infected Koreans [37] | The Korean Society for AIDS (Kr, 2019) | Korea | 2019 |

| Antiretroviral treatment for HIV infection: Swedish recommendations 2019 [38] | Eriksen J. et al. (Swe, 2019) | Sweden | 2019 |

| BHIVA guidelines on antiretroviral treatment for adults living with HIV-1 2022 [39] | British HIV Association (UK, 2022) | United Kingdom | 2022 |

| British HIV Association guidelines for the management of HIV in pregnancy and postpartum 2018 (2019 s interim update) [40] | British HIV Association (UK, 2019) | United Kingdom | 2019 |

| British HIV Association guidelines for the management of HIV-2 2021 [41] | Reeves I., et al. (UK, 2021) | United Kingdom | 2021 |

| Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults 2022 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA Panel [42] | Gandhi R. T. et al. (US, 2022a) | USA | 2022 |

| Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV [7] | Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV (US, 2023a) | USA | 2023 |

| Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV [43] | Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, Department of Health and Human Services (US, 2022b) | USA | 2022 |

| Primary Care Guidance for Persons With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: 2020 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America [44] | Thompson M.A., et al. (US, 2021) | USA | 2021 |

| Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States [45] | Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission (US, 2023b) | USA | 2023 |

| Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery and monitoring: recommendations for a public health approach [46] | World Health Organization (WHO, 2021a) | Geneva, Switzerland | 2021 |

| Consolidated guidelines on HIV, viral hepatitis and STI prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations [47] | World Health Organization (WHO, 2022) | Geneva, Switzerland | 2022 |

| Consolidated guidelines on person-centred HIV patient monitoring and case surveillance [48] | World Health Organization (WHO, 2017) | Geneva, Switzerland | 2017 |

| Consolidated HIV strategic information guidelines: Driving impact through programme monitoring and management [49] | World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) | Geneva, Switzerland | 2020 |

| Update of recommendations on first- and second-line antiretroviral regimens [50] | World Health Organization (WHO, 2019) | Geneva, Switzerland | 2019 |

| Updated recommendations on service delivery for the treatment and care of people living with HIV [51] | World Health Organization (WHO, 2021b) | Geneva, Switzerland | 2021 |

| Guideline | BC (2020) | ON | QC (2021) | Bel (2022) | EACS (2022) | Fr (2018a) | Fr (2019) | Fr (2018b) | Kr (2019) | Swe (2019) | UK (2022) | UK (2019) | UK (2021) | US (2022a) | US (2023a) | US (2022b) | US (2021) | US (2023b) | WHO (2021a) | WHO (2022) | WHO (2017) | WHO (2020) | WHO (2019) | WHO (2021b) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | . | . | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Threshold | . | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interventions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Enhance knowledge and skills | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 16 | ||||||||

| Provider training | . | . | . | . | . | . | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Optimize treatment or care | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Optimized ART | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 15 | |||||||||

| Mobile care | . | . | . | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Support psychosocial or daily needs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General support | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 14 | ||||||||||

| Mental health | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 14 | ||||||||||

| Finance support | . | . | . | . | . | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Harm reduction | . | . | . | . | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Promote adherence behaviors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronic reminders | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Physical reminder | . | . | . | . | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tailored, multidisciplinary approaches | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Multidisciplinary | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| Tailored support | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Targeting barriers | . | . | . | . | . | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Barriers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lifestyle factors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lifestyle or activities | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 11 | ||||||||||||

| Cognitive and emotional aspects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mental health | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 11 | ||||||||||||||

| Beliefs and health literacy | . | . | . | . | . | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Characteristics of ART | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medications | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 11 | |||||||||||||

| Healthcare services and system | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Health system | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| Healthcare provider | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 8 | ||||||||||||||||

| Health experience and state | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demographic group | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| Co-morbidities | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| Social and material context | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Social | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| Financial | . | . | . | . | . | . | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cultural or language | . | . | . | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Methods | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clinical evaluation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clinical assessment | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 12 | ||||||||||||

| Self-report | . | . | . | . | . | . | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tailored assessment | . | . | . | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lab-based monitoring | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Viral load/CD4 monitoring | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 13 | |||||||||||

| Drug monitoring | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Mutation or resistance tests | . | . | . | . | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Medication supply and monitoring tools | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharmacy records or pill count | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Electronic measures | . | . | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Routine or scheduled monitoring | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Specific intervals | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 13 | |||||||||||

| Every visit | . | . | . | . | . | . | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Context-driven monitoring | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Suspected virologic failure | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 8 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pregnancy | . | . | . | . | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Opportunistic infection | . | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency for Measuring Adherence | Methods for Monitoring Adherence | Interventions for Addressing Barriers to Adherence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada |

|

|

|

| Belgium |

|

|

|

| European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) |

|

|

|

| France |

|

|

|

| Korea |

|

|

|

| Sweden |

|

|

|

| United Kingdom |

|

|

|

| United States |

|

|

|

| World Health Organization (WHO) |

|

|

|

| General Population | Pregnant Women | Transgender People | People Who Use Substances | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhance knowledge and skills * |  |  |  | |

| Optimize treatment or care delivery † |  | |||

| Support psychosocial or daily needs ‡ |  |  |  |  |

| Promote adherence behaviors § |  |  | ||

| Tailored, multidisciplinary approaches ~ |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, D.; Engler, K.; Schuster, T.; Palich, R.; Ishak, J.; Lebouché, B. A Scoping Review of How High-Income Country HIV Guidelines Define, Assess, and Address Oral ART Adherence. Venereology 2025, 4, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology4030011

Chu D, Engler K, Schuster T, Palich R, Ishak J, Lebouché B. A Scoping Review of How High-Income Country HIV Guidelines Define, Assess, and Address Oral ART Adherence. Venereology. 2025; 4(3):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology4030011

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Dominic, Kim Engler, Tibor Schuster, Romain Palich, Joel Ishak, and Bertrand Lebouché. 2025. "A Scoping Review of How High-Income Country HIV Guidelines Define, Assess, and Address Oral ART Adherence" Venereology 4, no. 3: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology4030011

APA StyleChu, D., Engler, K., Schuster, T., Palich, R., Ishak, J., & Lebouché, B. (2025). A Scoping Review of How High-Income Country HIV Guidelines Define, Assess, and Address Oral ART Adherence. Venereology, 4(3), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology4030011