Condom Use Rate and Associated Factors among Undergraduate Students of Gulu University, Uganda

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Sample Size Determination

2.5. Sampling Procedure

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

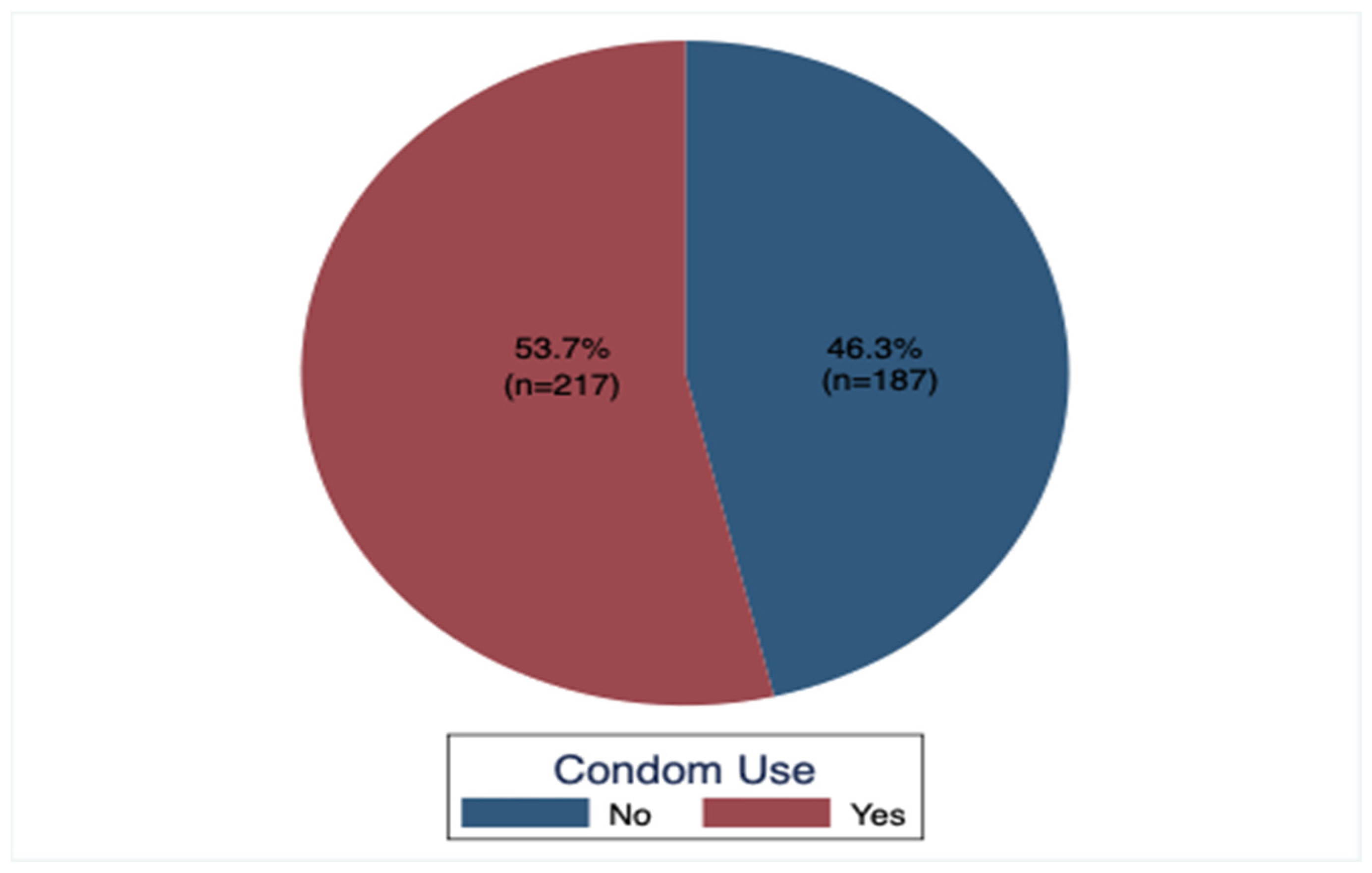

3.2. Condom Use Rate among All the Study Participants

3.3. Type of Condom Used by All the Study Participants

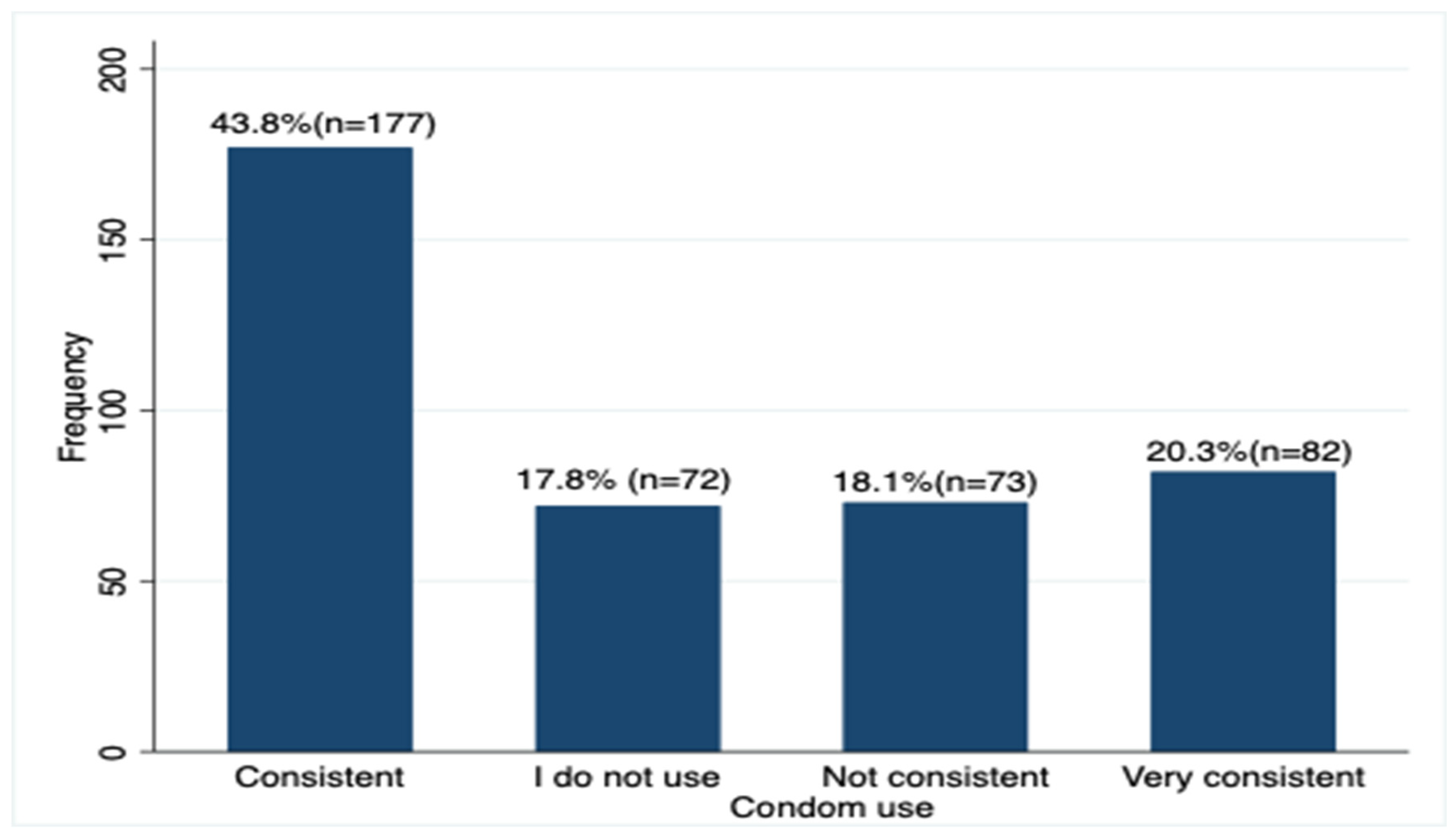

3.4. Consistency in Condom Use by the Participants

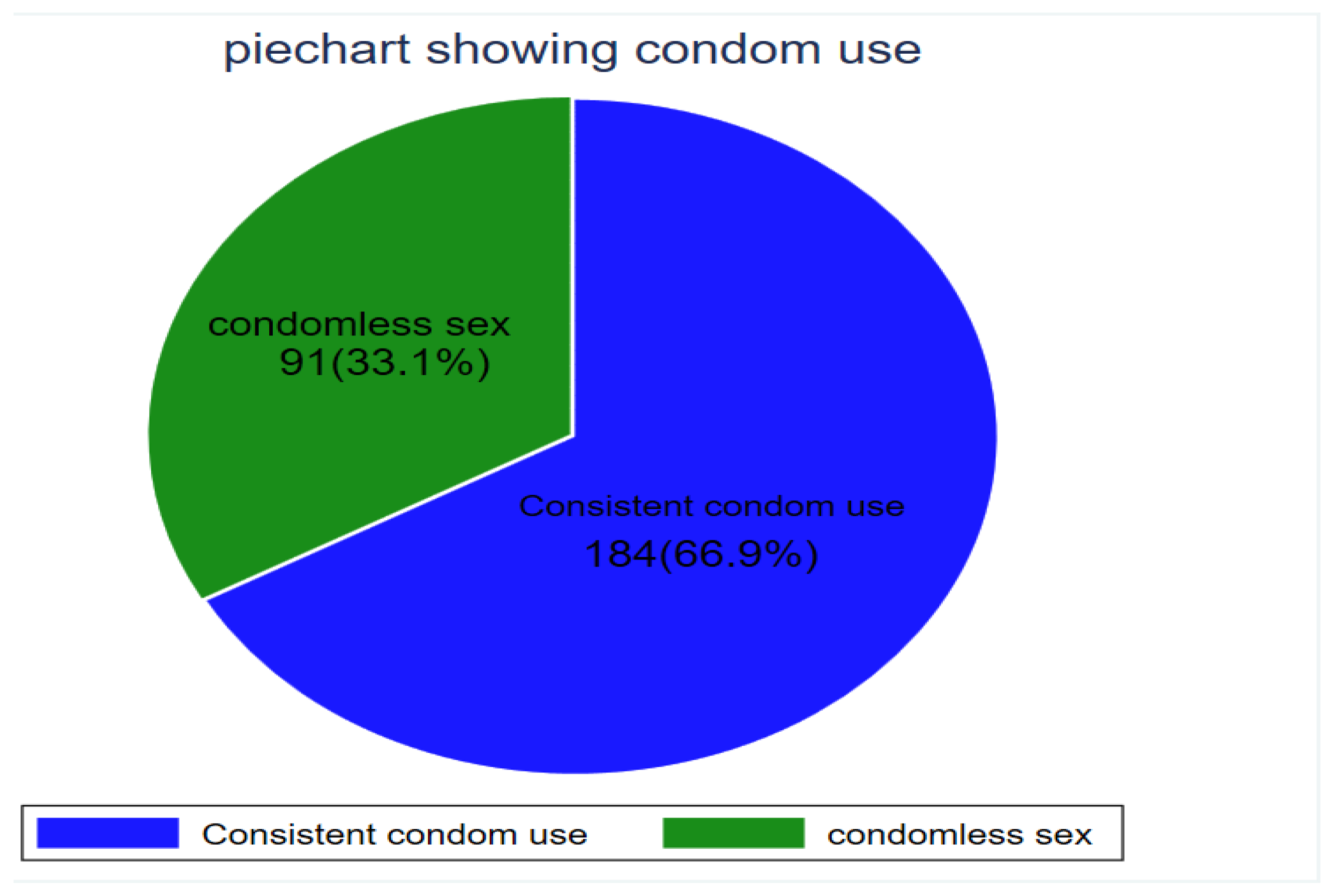

3.5. Consistency in Condom Use Rate among Participants Who Had Sex in the Last Six Months

3.6. Factors Associated with Condom Use

3.7. Factors Independently Associated with Condom Use

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Associated with Condom Use among the Undergraduate Students

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Treibich, C.; Lépine, A. Estimating misreporting in condom use and its determinants among sex workers: Evidence from the list randomisation method. Health Econ. 2019, 28, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Condoms and STDs: Fact Sheet for Public Health Personnel; Male Latex Condoms and Sexually Transmitted Diseases; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011.

- CDC, OID, NCHHSTP. CDC Fact Sheet: Consistent and Correct Condom Use; Department of Health & Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Information, S. SIECUS fact sheet: Comprehensive sexuality education. The truth about latex condoms. SIECUS Rep. 1993, 21, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Stover, J.; Teng, Y. The impact of condom use on the HIV epidemic. Gates Open Res. 2022, 5, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. WHO|HIV and Youth; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Chen, R.; Huang, D.; Wu, H.; Yan, H.; Li, S.; Braun, K.L. Prevalence of condom use and associated factors among Chinese female undergraduate students in Wuhan, China. AIDS Care 2013, 25, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinyaphong, J.; Srithanaviboonchai, K.; Chariyalertsak, S.; Phornphibul, P.; Tangmunkongvorakul, A.; Musumari, P.M. Inconsistent Condom Use Among Male University Students in Northern Thailand. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health 2018, 30, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshiekh, H.F.; Hoving, C.; de Vries, H. Exploring Determinants of Condom Use among University Students in Sudan. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gräf, D.D.; Mesenburg, M.A.; Fassa, A.G. Risky sexual behavior and associated factors in undergraduate students in a city in Southern Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica 2020, 54, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.R.; Dumith, S.C.; Paludo, S.D.S. Condom use in last sexual intercourse among undergraduate students: How many are using them and who are they? Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2018, 23, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fact Sheet on the Uganda Population HIV Impact Assessment.|WHO|Regional Office for Africa. 2017. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/fact-sheet-uganda-population-hiv-impact-assessment (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Gulu University Main Campus/Branch—Admissions. 2022. Available online: https://admissions.co.ug/gulu-university-main-campus/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- List of Gulu University Faculties and Schools—Admissions. 2022. Available online: https://admissions.co.ug/list-of-gulu-university-faculties/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Labat, A.; Medina, M.; Elhassein, M.; Karim, A.; Jalloh, M.B.; Dramaix, M.; Zhang, W.H.; Alexander, S.; Dickson, K.E. Contraception determinants in youths of Sierra Leone are largely behavioral. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szucs, L.E.; Lowry, R.; Fasula, A.M.; Pampati, S.; Copen, C.E.; Hussaini, K.S.; Kachur, R.E.; Koumans, E.H.; Steiner, R.J. Condom and Contraceptive Use Among Sexually Active High School Students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020, 69, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomazana, N.; Maharaj, P. The prevalence of condom use among university students in Zimbabwe: Implications for planning and policy. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2013, 45, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izudi, J.; Okello, G.; Semakula, D.; Bajunirwe, F. Low condom use at the last sexual intercourse among university students in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Han, Y.; Tong, L.; Chen, Z. Association between condom use and perspectives on contraceptive responsibility in different sexual relationships among sexually active college students in China: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2019, 98, e13879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Giron, C.A.; Cruz-Valdez, A.; Quiterio-Trenado, M.; Uribe-Salas, F.; Peruga, A.; Hernández-Avila, M. Factors associated with condom use in the male population of Mexico City. Int. J. STD AIDS 1999, 10, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.C.; Rosa MI da Battisti, I.D.E. Prevalence of condom use and associated factors in a sample of university students in southern Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica 2009, 25, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yosef, T.; Nigussie, T. Behavioral Profiles and Attitude toward Condom Use among College Students in Southwest Ethiopia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 9582139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, P. Reasons for condom use among young people in KwaZulu-Natal: Prevention of HIV, pregnancy or both? Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 2006, 32, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houéto, D.S.; N’Koué N’Da, E.B.; Sambiéni, E.N. Factors Associated with Condom Use Among High School Students of Natitingou Agricultural Technical School, Benin, in 2017. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2021, 41, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, A.I.; Ismail, K.O.; Akpan, W. Factors associated with consistent condom use: A cross-sectional survey of two Nigerian universities. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, C.P.; Canaval, G.E. Factors predisposing, facilitating and strengthening condom use amongst university students in Cali, Colombia. Rev. Salud Pública 2012, 14, 810–821. [Google Scholar]

- Fauk, N.K.; Kustanti, C.Y.; Liana, D.S.; Indriyawati, N.; Crutzen, R.; Mwanri, L. Perceptions of Determinants of Condom Use Behaviors Among Male Clients of Female Sex Workers in Indonesia: A Qualitative Inquiry. Am. J. Mens. Health 2018, 12, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phiri, S.S.; Rikhotso, R.; Moagi, M.M.; Bhana, V.M.; Jiyane, P.M. Accessibility and availability of the Female Condom2: Healthcare provider’s perspective. Curationis 2015, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hock-Long, L.; Henry-Moss, D.; Carter, M.; Hatfield-Timajchy, K.; Erickson, P.I.; Cassidy, A.; MacAuda, M.; Singer, M.; Chittams, J. Condom use with serious and casual heterosexual partners: Findings from a community venue-based survey of young adults. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, I.R.; de Bessa Guimarães, I.; Franco, G.M.; Silva, A.M.T.C. Factors associated with the use of condom and knowledge about HIV/AIDS among medical students. Hum. Reprod. Arch. 2020, 35, e000520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauni, E.K.; Jarabi, B.O. The Low Acceptability and Use of Condoms within Marriage: Evidence from Nakuru District, Kenya. Afr. Popul. Stud. 2003, 18, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, C.J.; Jeffries, R.A.; Afifi, A.A.; Cumberland, W.G.; Chung, E.Q.; Kerndt, P.R.; Ethier, K.A.; Martinez, E.; Loya, R.V.; Dittus, P.J. Improving the implementation of a condom availability program in urban high schools. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 51, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wretzel, S.R.; Visintainer, P.F.; Pinkston Koenigs, L.M. Condom availability program in an inner city public school: Effect on the rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia infection. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 49, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.B.; Noar, S.M.; Widman, L.; Willoughby, J.F.; Sanchez, D.M.; Garrett, K.P. Perceptions of a campus-wide condom distribution programme: An exploratory study. Health Educ. J. 2016, 75, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charania, M.R.; Crepaz, N.; Guenther-Gray, C.; Henny, K.; Liau, A.; Willis, L.A.; Lyles, C.M. Efficacy of structural-level condom distribution interventions: A meta-analysis of U.S. and international studies, 1998–2007. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 1283–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables/Response | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 23 | 21.5–24 |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 185 | 45.8 |

| Men | 219 | 54.2 |

| Faculty | ||

| Agriculture and environment | 64 | 15.8 |

| Business and development studies | 55 | 13.6 |

| Education and humanities | 85 | 12.0 |

| Medicine | 56 | 13.9 |

| Science | 94 | 23.3 |

| Law | 50 | 12.4 |

| Year of study | ||

| 1 | 75 | 18.6 |

| 2 | 131 | 32.4 |

| 3 | 141 | 34.9 |

| 4 | 41 | 10.2 |

| 5 | 16 | 3.9 |

| Have sexual partner? | ||

| No | 196 | 48.5 |

| Yes | 208 | 51.5 |

| If yes, nature of the relationship? | ||

| Casual | 63 | 30.3 |

| Married | 12 | 5.8 |

| Stable | 133 | 63.9 |

| Source of sexual partner? | ||

| Out of campus | 237 | 58.7 |

| Within campus | 167 | 41.3 |

| Had sex in the last 6 months? | ||

| No | 129 | 31.9 |

| Yes | 275 | 68.1 |

| If yes, did you use condom? | ||

| No | 58 | 21.1 |

| Yes | 217 | 78.9 |

| Engagement in buying or selling sex? | ||

| No | 390 | 96.5 |

| Yes | 14 | 3.5 |

| Aware of HIV status? | ||

| No | 50 | 12.4 |

| Yes | 354 | 87.6 |

| If yes, what is the HIV status? | ||

| Negative | 351 | 99.1 |

| Positive | 3 | 0.9 |

| Carrying out HIV testing before having sex? | ||

| No | 267 | 66.1 |

| Yes | 137 | 33.9 |

| If yes, from where? | ||

| From nearby clinic | 63 | 46 |

| From the university health unit | 22 | 16.1 |

| Self-testing | 52 | 37.9 |

| Heard of PrEP? | ||

| No | 297 | 73.5 |

| Yes | 107 | 26.5 |

| Heard of PEP? | ||

| No | 236 | 58.4 |

| Yes | 168 | 41.6 |

| Ever experienced condom bursting? | ||

| No | 339 | 84.5 |

| Yes | 62 | 15.5 |

| Do you use any other method of contraceptive? | ||

| No | 287 | 71.2 |

| Yes | 116 | 28.8 |

| If yes, which one? | ||

| Emergency pills | 104 | 88.1 |

| Injectables | 14 | 11.9 |

| In absence of condoms? | ||

| No sex | 251 | 62.1 |

| Proceed to have sex | 153 | 37.9 |

| Do you drink alcohol? | ||

| No | 278 | 68.8 |

| Yes | 126 | 31.2 |

| How often do you drink alcohol? | ||

| Daily | 1 | 0.3 |

| I don’t drink alcohol. | 277 | 68.6 |

| Occasionally | 126 | 31.1 |

| Been using condom under influence of alcohol? | ||

| No | 397 | 98.3 |

| Yes | 7 | 1.7 |

| Variable | ALL 275 (100%) | Consistent Condom Use 184 (66.9%) | Condomless Sex 91 (33.1%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, | ||||

| Median (IQR%), years | 23 (22–25) years | |||

| 20–22 years | 110 (40.0%) | 73 (26.6%) | 37 (13.6%) | 0.182 |

| 23–25 years | 130 (47.3%) | 92 (33.4%) | 38 (13.8%) | |

| >25 years | 35 (12.7%) | 19 (6.9%) | 16 (5.8%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 134 (48.7%) | 84 (30.6%) | 50 (18.8%) | 0.147 |

| Men | 141 (51.3%) | 100 (36.4%) | 41 (14.9%) | |

| Faculty | ||||

| Agriculture and environment | 45 (16.4%) | 27 (9.8%) | 18 (6.6%) | 0.092 |

| Business and development | 33 (12.0%) | 19 (6.9%) | 14 (5.1%) | |

| Education and humanities | 50 (18.2%) | 29 (10.6%) | 21 (7.6%) | |

| Law | 44 (16.0%) | 29 (10.6%) | 15 (5.5%) | |

| Medicine | 72 (26.2%) | 56 (20.4%) | 16 (5.8%) | |

| Science | 31 (11.3%) | 24 (8.7%) | 7 (2.5%) | |

| Year of study | ||||

| 1 | 26 (9.5%%) | 18 (6.6%) | 8 (2.9%) | 0.818 |

| 2 | 88 (32.0%) | 58 (21.1%) | 30 (10.9%) | |

| 3 | 107 (38.9%) | 70 (25.5%) | 37 (13.5%) | |

| 4 | 38 (13.8%) | 25 (9.1%) | 13 (4.7%) | |

| 5 | 15 (5.8%) | 13 (4.7%) | 3 (1.1%) | |

| Have sexual partner | ||||

| Yes | 185 (67.3%) | 136 (49.5%) | 49 (17.8%) | 0.001 |

| No | 90 (32.7%) | 48 (17.5%) | 42 (15.3%) | |

| If yes, what is the nature of the relationship | ||||

| Casual | 58 (31.4%) | 45 (24.3%) | 13 (7.0%) | <0.001 |

| Married | 10 (5.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (5.4%) | |

| Stable | 117 (63.2%) | 91 (49.2%) | 26 (14.1%) | |

| Source of your sexual partner | ||||

| Out of campus | 40 (21.6%) | 23 (12.4%) | 17 (9.2%) | 0.010 |

| Within campus | 145 (78.4%) | 113 (61.1%) | 32 (17.3%) | |

| Had sex in the last 6 months | ||||

| Yes | 275 (100%) | 184 (66.91%) | 91 (33.09%) | |

| Engagement in buying or selling sex | ||||

| Yes | 11 (4.0%) | 8 (2.9%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0.676 |

| No | 264 (96.0%) | 176 (64.0%) | 88 (32.0%) | |

| Aware of HIV status | ||||

| Yes | 243 (88.4%) | 161 (58.6%) | 82 (29.8%) | 0.525 |

| No | 32 (11.6%) | 23 (8.36%) | 9 (3.3%) | |

| If yes, what is the HIV status | ||||

| Negative | 241 (99.2%) | 159 (65.4%) | 82 (33.7%) | 0.551 |

| Positive | 2 (0.8%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Carrying out HIV testing before having sex | ||||

| No | 177 (64.4%) | 118 (42.9%) | 59 (21.5%) | 0.909 |

| Yes | 98 (35.6%) | 66 (24.0%) | 32 (11.6%) | |

| If yes, from where? | ||||

| From nearby clinic | 45 (45.9%) | 26 (26.5%) | 19 (19.4%) | 0.127 |

| From the university health unit | 19 (19.4%) | 13 (13.3%) | 6 (6.1%) | |

| Self-testing | 34 (34.7%) | 27 (27.6%) | 7 (7.1%) | |

| Heard of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) | ||||

| Yes | 77 (28.0%) | 60 (21.8%) | 17 (6.2%) | 0.016 |

| No | 198 (72.0%) | 124 (45.1%) | 74 (26.9%) | |

| Heard of post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) | ||||

| Yes | 120 (43.6%) | 89 (32.4%) | 31 (11.3%) | 0.024 |

| No | 155 (56.4%) | 95 (34.6%) | 60 (21.8%) | |

| Ever experienced condom bursting | ||||

| Yes | 50 (18.3%) | 38 (13.9%) | 12 (4.4%) | 0.141 |

| No | 224 (81.7%) | 146 (53.3%) | 78 (28.5%) | |

| Do you use any other method of contraceptive | ||||

| Yes | 90 (32.7%) | 56 (20.4%) | 34 (12.4%) | 0.276 |

| No | 185 (67.3%) | 128 (46.6%) | 57 (20.7%) | |

| If yes, which one | ||||

| Emergency pills | 80 (89.9%) | 49 (55.1%) | 31 (34.8%) | 0.751 |

| Injectables | 9 (10.1%) | 6 (6.7%) | 3 (3.4%) | |

| In absence of condoms | ||||

| No sex | 174 (63.3%%) | 158 (57.5%) | 16 (5.8%) | <0.001 |

| Proceed to have sex | 101 (36.7%) | 26 (9.5%) | 75 (27.3%) | |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| Yes | 96 (34.9%) | 63 (22.9%) | 33 (12.0%) | 0.740 |

| No | 179 (65.1%) | 121 (44.0%) | 58 (21.1%) | |

| Condom use under influence of alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 7 (2.6%) | 6 (2.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.431 |

| No | 268 (97.5%) | 178 (64.7%) | 90 (32.7%) | |

| Where can one access condoms from while at campus? | ||||

| University health unit | 112 (40.7%) | 66 (24.0%) | 46 (16.7%) | 0.004 |

| Friends | 23 (8.4%) | 15 (5.5%) | 8 (2.9%) | |

| Gents/ladies | 16 (5.82%) | 9 (3.3%) | 7 (2.6%) | |

| University health unit and friends | 112 (40.7%) | 89 (32.4%) | 23 (8.4%) | |

| I don’t know | 12 (4.4%) | 5 (1.8%) | 7 (2.6%) | |

| Variable | Consistent Condom Use 184 (66.9%) | Condomless Sex 91 (33.1%) | aPR (95% Confidence Interval) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, | ||||

| Median (IQR), years | 23 (22–25) years | |||

| 20–22 years | 73 (26.6%) | 37 (13.6%) | Reference | Reference |

| 23–25 years | 92 (33.4%) | 38 (13.8%) | 1.06 (0.89–1.25) | 0.527 |

| >25 years | 19 (6.9%) | 16 (5.8%) | 1.33 (0.99–1.80) | 0.057 |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 84 (30.6%) | 50 (18.8%) | Reference | Reference |

| Men | 100 (36.4%) | 41 (14.9%) | 0.82 (0.71–0.95) | 0.011 |

| nature of sexual relationship | ||||

| Casual | 45 (24.3%) | 13 (7.0%) | Reference | Reference |

| Married | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (5.4%) | 1.40 (1.07–1.85) | 0.015 |

| Stable | 91 (49.2%) | 26 (14.1%) | 1.07 (0.89–1.27) | 0.418 |

| Source of sexual partner | ||||

| Out of campus | 23 (12.4%) | 17 (9.2%) | Reference | Reference |

| Within campus | 113 (61.1%) | 32 (17.3%) | 0.98 (0.99–1.85) | 0.809 |

| from where u had your HIV tested? | ||||

| From nearby clinic | 26 (26.5%) | 19 (19.4%) | Reference | Reference |

| From the university health unit | 13 (13.3%) | 6 (6.1%) | 1.22 (1.06–1.41) | 0.005 |

| Self-testing | 27 (27.6%) | 7 (7.1%) | 1.13 (0.96–1.32) | 0.134 |

| Heard of pre-exposure prophylaxis | ||||

| Yes | 60 (21.8%) | 17 (6.2%) | Reference | Reference |

| No | 124 (45.1%) | 74 (26.9%) | 0.98 (0.74–1.31) | 0.895 |

| Heard of post exposure prophylaxis | ||||

| Yes | 89 (32.4%) | 31 (11.3%) | Reference | Reference |

| No | 95 (34.6%) | 60 (21.8%) | 1.04 (0.90–1.20) | 0.581 |

| Ever experienced condom bursting | ||||

| Yes | 38 (13.9%) | 12 (4.4%) | Reference | Reference |

| No | 146 (53.3%) | 78 (28.5%) | 1.03 (0.82–1.29) | 0.781 |

| In absence of condoms | ||||

| No sex | 158 (57.5%) | 16 (5.8%) | Reference | Reference |

| Proceed to have sex | 26 (9.5%) | 75 (27.3%) | 1.22 (1.01–1.46) | 0.021 |

| Where can one access condoms from while at campus? | ||||

| University health unit | 66 (24.0%) | 46 (16.7%) | Reference | Reference |

| Friends | 15 (5.5%) | 8 (2.9%) | 0.99 (0.71–1.38) | 0.956 |

| Gents/ladies | 9 (3.3%) | 7 (2.6%) | 1.53 (0.93–2.51) | 0.092 |

| University health unit and friends | 89 (32.4%) | 23 (8.4%) | 1.17 (0.85–1.63) | 0.337 |

| I don’t know | 5 (1.8%) | 7 (2.6%) | 1.12 (0.77–1.62) | 0.560 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Otim, B.; Okot, J.; Nannungi, C.; Nantale, R.; Kibone, W.; Madraa, G.; Okot, C.; Bongomin, F. Condom Use Rate and Associated Factors among Undergraduate Students of Gulu University, Uganda. Venereology 2024, 3, 147-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology3030012

Otim B, Okot J, Nannungi C, Nantale R, Kibone W, Madraa G, Okot C, Bongomin F. Condom Use Rate and Associated Factors among Undergraduate Students of Gulu University, Uganda. Venereology. 2024; 3(3):147-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology3030012

Chicago/Turabian StyleOtim, Brian, Jerom Okot, Christine Nannungi, Ritah Nantale, Winnie Kibone, Grace Madraa, Christopher Okot, and Felix Bongomin. 2024. "Condom Use Rate and Associated Factors among Undergraduate Students of Gulu University, Uganda" Venereology 3, no. 3: 147-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology3030012

APA StyleOtim, B., Okot, J., Nannungi, C., Nantale, R., Kibone, W., Madraa, G., Okot, C., & Bongomin, F. (2024). Condom Use Rate and Associated Factors among Undergraduate Students of Gulu University, Uganda. Venereology, 3(3), 147-161. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology3030012