Recurrent Candida Vulvovaginitis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology

3. Etiology

4. Pathogenesis

5. Vaginal Microbiome and Risk Factors for Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

6. Clinical Manifestations

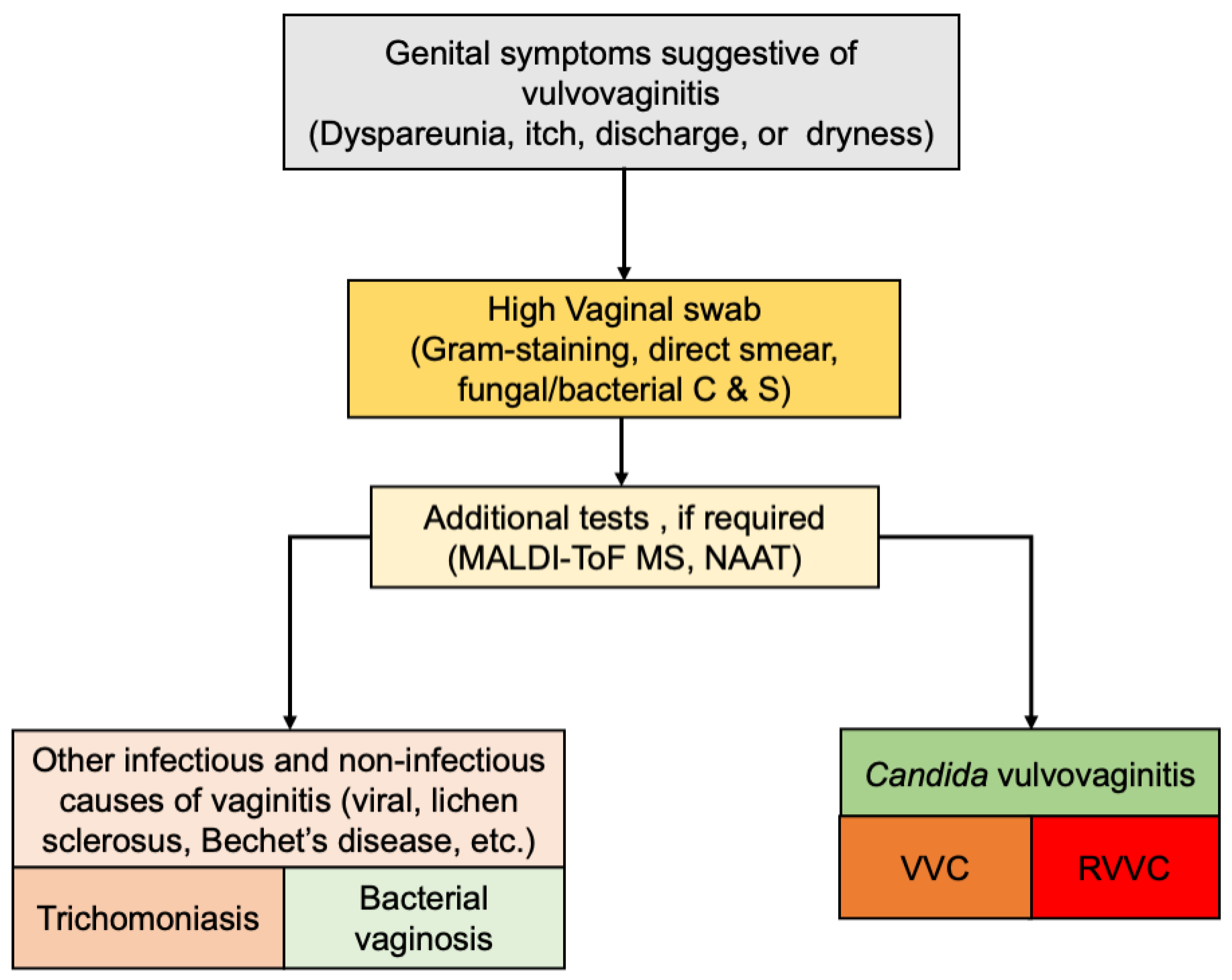

7. Diagnosis

8. Current Treatment Options for Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilkinson, J.S. Some remarks upon the development of epiphytes with the description of new vegetable formation found in connexion with the human uterus. Lancet 1849, 54, 448–451. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.D.; Denning, D.W.; Gow, N.A.R.; Levitz, S.M.; Netea, M.G.; White, T.C. Hidden killers: Human fungal infections. Sci. Transl. Med 2012, 4, 165rv13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Denning, D.W.; Kneale, M.; Sobel, J.D.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: A systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, e339–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, J.D. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidel, P.L., Jr.; Barousse, M.; Espinosa, T.; Ficarra, M.; Sturtevant, J.; Martin, D.H.; Quayle, A.J.; Dunlap, K. An intravaginal line candida challenge in humans leads to new hypotheses for the immunopathogenesis of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 2939–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barajas, J.F.; Wehrs, M.; To, M.; Cruickshanks, L.; Urban, R.; McKee, A.; Gladden, J.; Goh, E.-B.; Brown, M.E.; Pierotti, D.; et al. Isolation and characterization of bacterial cellulase Producers for biomass deconstruction. A microbiology laboratory course. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2019, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.M. Innate host defense of human vaginal and cervical mucosae. In Antimicrobial Peptides and Human Disease. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 306, pp. 199–230. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati, D.; Bruno, M.; Jaeger, M.; Ten Oever, J.; Netea, M.G. Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: An Immunological Perspective. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sobel, J.D.; Faro, S.; Force, R.W.; Foxman, B.; Ledger, W.; Nyirjesy, P.R.; Reed, B.D.; Summers, P.R. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol 1998, 178, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deorukhkar, S.C.; Saini, S.; Mathew, S. Non-albicans Candida infection: An emerging threat. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2014, 2014, 615958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.R.; Klink, K.; Cohrssen, A. Evaluation of vaginal complaints. JAMA 2004, 291, 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makanjuola, O.; Bongomin, F.; Fayemiwo, S.A. An update on the roles of non-albicans Candida species in vulvovaginitis. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fidel, P.L.; Vazquez, J.A.; Sobel, J.D. Candida glabrata: Review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mayer, F.L.; Wilson, D.; Hube, B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence 2013, 4, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zangl, I.; Pap, I.J.; Aspock, C.; Schuller, C. The role of Lactobacillus species in the control of Candida via biotrophic interactions. Microb. Cell 2019, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyes, D.L.; Richardson, J.P.; Naglik, J. Candida albicans-epithelial interactions and pathogenicity mechanisms: Scratching the surface. Virulence 2015, 6, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kalia, N.; Singh, J.; Kaur, M. Microbiota in vaginal health and pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal infections: A critical review. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauchie, M.; Desmet, S.; Lagrou, K. Candida and its dual lifestyle as a commensal and a pathogen. Res. Microbiol. 2017, 168, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Willems, H.M.E.; Moyes, D.L.; Shoaie, S.; Barker, K.S.; Tan, S.L.; Palmer, G.E.; Hube, B.; Naglik, J.R.; Peters, B.M. Candidalysin Drives Epithelial Signaling, Neutrophil Recruitment, and Immunopathology at the Vaginal Mucosa. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00645-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ardizzoni, A.; Wheeler, R.T.; Pericolini, E. It Takes Two to Tango: How a Dysregulation of the Innate Immunity, CoupledWith Candida Virulence, Triggers VVC Onset. Front. Microbiol 2021, 12, 692491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, H.M.E.; Ahmed, S.S.; Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Peters, B.M. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Current Understanding and Burning Questions. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wachtler, B.; Citiulo, F.; Jablonowski, N.; Forster, S.; Dalle, F.; Schaller, M.; Wilson, D.; Hube, B. Candida albicans-epithelial interactions: Dissecting the roles of active penetration, induced endocytosis and host factors on the infection process. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Re, A.C.S.; Martins, J.F.; Cunha-Filho, M.; Gelfuso, G.M.; Aires, C.P.; Gratieri, T. New perspectives on the topical management of recurrent candidiasis. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 11, 1568–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravel, J.; Gajer, P.; Abdo, Z.; Schneider, G.M.; Koenig, S.S.; McCulle, S.L.; Karlebach, S.; Gorle, R.; Russell, J.; Tacket, C.O.; et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4680–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valenti, P.; Rosa, L.; Capobianco, D.; Lepanto, M.S.; Schiavi, E.; Cutone, A.; Paesano, R.; Mastromarino, P. Role of Lactobacilli and Lactoferrin in the Mucosal Cervicovaginal Defense. Front. Immunol 2018, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykke, M.R.; Becher, N.; Haahr, T.; Boedtkjer, E.; Jensen, J.S.; Uldbjerg, N. Vaginal, Cervical and Uterine pH in Women with Normal and Abnormal Vaginal Microbiota. Pathogens 2021, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.A.; Beasley, D.E.; Dunn, R.R.; Archie, E.A. Lactobacilli Dominance and Vaginal pH: Why Is the Human Vaginal Microbiome Unique? Front. Microbiol. 2016, 61, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauters, T.G.; Dhont, M.A.; Temmerman, M.I.; Nelis, H.J. Prevalence of vulvovaginal candidiasis and susceptibility to fluconazole in women. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol 2002, 187, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, J.D.; Wiesenfeld, H.C.; Martens, M.; Danna, P.; Hooton, T.M.; Rompalo, A.; Sperling, M.; Livengood, C., 3rd; Horowitz, B.; Von Thron, J.; et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blostein, F.; Levin-Sparenberg, E.; Wagner, J.; Foxman, B. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Ann. Epidemio. 2017, 27, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workowski, K.A.; Bolan, G.A. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm. Rep. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Recomm. Rep. 2015, 64, 1–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gonçalves, B.; Ferreira, C.; Alves, C.T.; Henriques, M.; Azeredo, J.; Silva, S. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 905–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lema, V.M. Recurrent Vulvo-Vaginal Candidiasis: Diagnostic and Management Challenges in a Developing Country Context. Obs. Gynecol. Int. J. 2017, 7, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W. Fungal Barcoding Consortium. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patel, R. A Moldy Application of MALDI: MALDI-ToF Mass Spectrometry for Fungal Identification. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gulati, M.; Nobile, C.J. Candida albicans biofilms: Development, regulation, and molecular mechanisms. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, S.S.; Xu, Y.; Triantafyllou, I.; Waldman, M.F.; Mendrick, C.; Brown, N.; Mann, P.; Chau, A.; Patel, R.; Bauman, N.; et al. Discovery of a novel class of orally active antifungal beta-1,3-D-glucan synthase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 5099–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghannoum, M.; Arendrup, M.C.; Chaturvedi, V.P.; Lockhart, S.R.; McCormick, T.S.; Chaturvedi, S.; Berkow, E.L.; Juneja, D.; Tarai, B.; Azie, N.; et al. Ibrexafungerp: A novel oral Triterpenoid antifungal in development for the treatment of Candida auris infections. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prutting, S.; Cerveny, J. Boric acid vaginal suppositories: A brief review. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1998, 6, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, J.D.; Chaim, W.; Nagappan, V.; Leaman, D. Treatment of vaginitis caused by Candida glabrata: Use of topical boric acid and flucytosine. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2003, 189, 297–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marchaim, D.; Lemanek, L.; Bheemreddy, S.; Kaye, K.S.; Sobel, J.D. Fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans vulvovaginitis. Obs. Gynecol. 2012, 120, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phillips, A.J. Treatment of non-albicans Candida vaginitis with amphotericin B vaginal suppositories. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2005, 192, 2009–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramage, G.; Rajendran, R.; Sherry, L.; Williams, C. Fungal biofilm resistance. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012, 2012, 528521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Betsi, G.I.; Athanasiou, S. Probiotics for prevention of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: A review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gardiner, G.E.; Heinemann, C.; Baroja, M.L.; Bruce, A.W.; Beuerman, D.; Madrenas, J.; Reid, G. Oral Administration of the Probiotic Combination Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GR-1 and L. Fermentum RC-14 for Human Intestinal Applications. Int. Dairy J. 2002, 12, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, B.D.; Pfeiffer, C.D.; Jimenez-Ortigosa, C.; Catania, J.; Booker, R.; Castanheira, M.; Messer, S.A.; Perlin, D.S.; Pfaller, M.A. Increasing echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata: Clinical failure correlates with FKS mutations and elevated minimum inhibitory concetrations. Clin. Infect. Dis 2013, 56, 1724–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beyda, N.D.; John, J.; Kilic, A.; Alam, M.J.; Lasco, T.M.; Garey, K.W. FKS mutant Candida glabrata: Risk factors and outcomes in patients with candidemia. Clin. Infect. Dis 2014, 59, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jimenez-Ortigosa, C.; Perez, W.B.; Angulo, D.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Perlin, D.S. Novo acquisition of resitance to SCY-078 in Candida glabrata involves FKS mutation that both overlap and are distinct from those conferring echinocandin resistance. Chemother. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 61, e00833-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larkin, E.L.; Long, L.; Isham, N.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Angulo, D.; Wring, S.; Ghannoum, M. A novel 1,3-Beta-d-Glucan inhibitor, Ibrexafungerp (formerly SCY-078), shows potent activity in the lower pH environment of vulvovaginitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02611-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phillips, N.A.; Bachmann, G.; Haefner, H.; Martens, M.; Stockdale, C. Topical Treatment of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: An Expert Consensus. Women’s Health Reports 2021, 3, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guideline Development Group Cara Saxon Lead Author; Edwards, A.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Owen, C.; Nathan, B.; Palmer, B.; Wood, C.; Ahmed, H.; Ahmad, S.; Patient Representatives, M.F.; et al. British association for sexual health and HIV national guideline for the management of vulvovaginal candidiasis (2019). Int. J. STD AIDS 2020, 31, 1124–1144. [Google Scholar]

| Antifungal Class (Example) | Mechanism of Action | Adverse Events | Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azoles (clotrimazole, fluconazole) [37] | Impaired ergosterol synthesis due to inhibition of 14-α-lanosterol demethylase | Anaphylaxis, phototoxicity, cardiomyopathy, gastrointestinal disturbances. | Mutation in ERG11, the gene coding for 14-α-lanosterol demethylase. |

| Echinocandins [38,39] (ibrexafungerp) | Inhibition of 1,3-β-D-glucan synthesis in fungal cell wall resulting in loss of structural integrity, osmotic instability, and cell death. | Hepatic toxicity | Mutations in glucan synthase complex genes. |

| Polyenes (Nystatin, Amphotericin B) [34] | Binds to ergosterol in fungi membranes to form pore and increase membrane permeability. | Nystatin; well-tolerated. Amphotericin B. Nephrotoxicity, hepatic toxicity | Resistance may be caused by replacement of ergosterol with precursor sterols. |

| Others: Boric acid [40] | Exact mechanism is unknown. Vaginal acidification causes cell membrane dysfunction. | Toxicity when systemically absorbed. |

| Intervention | Vulvovaginal Candidiasis | Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis |

|---|---|---|

| Recommended oral regimen | Non-pregnant: Fluconazole capsule 150 mg as a single dose. If oral therapy is contraindicated, clotrimazole pessary 500 mg as a single dose, intravaginally. Pregnancy: Clotrimazole pessary 500 mg PV at night for up to 7 nights. NAC spp and azole resistance: Nystatin pessaries 100,000 units intravaginally every night for 14 days | Non-pregnant: Induction: Fluconazole 150 mg orally every 72 h × 3 doses. Maintenance: Fluconazole 150 mg orally once a week for 6 months. Pregnancy: Induction: topical imidazole therapy for up to 10–14 days according to symptomatic response. Maintenance: clotrimazole pessaries 500 mg intravaginally weekly. NAC spp and azole resistance: Nystatin pessaries 100,000 unit intravaginally at night for 14 nights/month for 6 months. |

| Alternative regimens | Non-pregnant: Clotrimazole vaginal cream (10%) 5 g as a single dose OR Clotrimazole pessary 200 mg intravaginally at night for 3 consecutive nights OR Econazole pessary 150 mg intravaginally as a single dose or 150 mg intravaginally at night for 3 consecutive nights. OR Fenticonazole capsule intravaginally as a single dose 600 mg or 200 mg intravaginally at night for 3 consecutive days. OR Itraconazole 200 mg orally twice daily for 1 day PO. OR Miconazole capsule 1200 mg intravaginally as a single dose, or 400 mg intravaginally at night for 3 consecutive nights. OR Miconazole vaginal cream (2%) 5 g intravaginally at night for 7 consecutive nights. Pregnancy: Clotrimazole vaginal cream (10%) 5 g at night for up to 7 nights. OR Clotrimazole pessary 200 mg or 100 mg intravaginally at night for 7 nights OR Econazole pessary 150 mg intravaginally at night for 7 consecutive nights. OR Miconazole pessary 1200 mg or 400 mg intravaginally at night for 7 consecutive nights. OR Miconazole vaginal cream (2%) 5 g intravaginally at night for 7 consecutive nights. NAC spp and azole resistance: Boric acid suppositories 600 mg intravaginally at night for 14 nights. OR Amphotericin B vaginal suppositories 50 mg intravaginally at night for 14 nights. OR Flucytosine 5 g cream or 1 g pessary with amphotericin or nystatin intravaginally at night for 14 nights. | Non-pregnant: Induction: topical imidazole therapy can be increased to 7–14 days according to symptomatic response. Maintenance for 6 months: Clotrimazole pessary 500 mg intravaginally once a week. Itraconazole 50–100 mg orally daily. NAC spp and azole resistance: Consider 14 nights per month of the alternative regimens. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nsenga, L.; Bongomin, F. Recurrent Candida Vulvovaginitis. Venereology 2022, 1, 114-123. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology1010008

Nsenga L, Bongomin F. Recurrent Candida Vulvovaginitis. Venereology. 2022; 1(1):114-123. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology1010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleNsenga, Lauryn, and Felix Bongomin. 2022. "Recurrent Candida Vulvovaginitis" Venereology 1, no. 1: 114-123. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology1010008

APA StyleNsenga, L., & Bongomin, F. (2022). Recurrent Candida Vulvovaginitis. Venereology, 1(1), 114-123. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology1010008