One Sheet Does Not Fit All: The Dietetic Treatment Experiences of Individuals with High Eating Disorder Symptomatology Attending a Metabolic and Bariatric Clinic; an Exploratory Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics and Background

2.3.2. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire Short (EDE-QS)

2.3.3. Eating Disorder Treatment Experiences Survey (EDTES)

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Exploratory Quantitative Analyses

2.4.2. Qualitative Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Quantitative Dietitian Results

3.3. Qualitative Dietitian Results

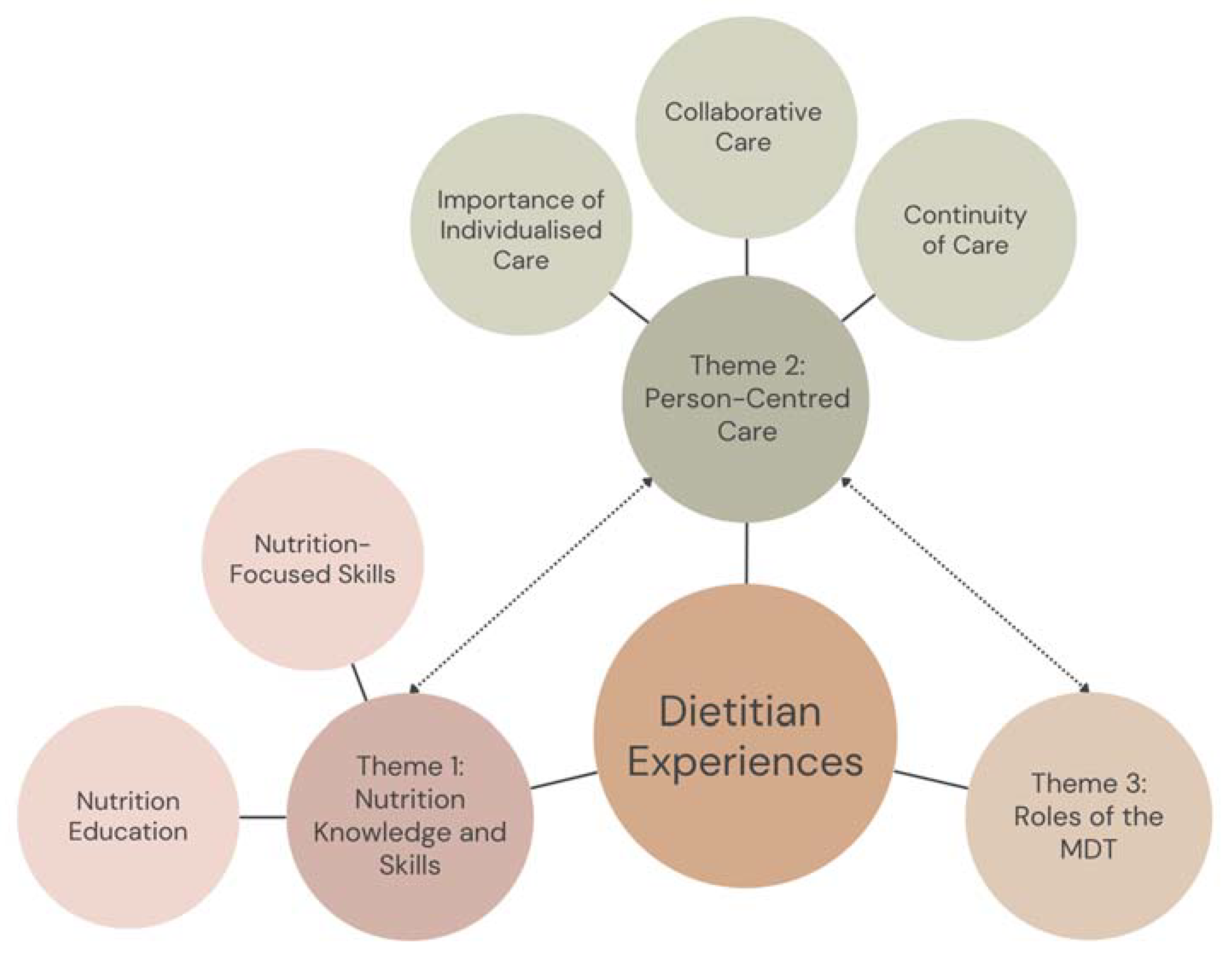

3.3.1. Theme 1: Nutrition Knowledge and Skills

Subtheme 1(a): Nutrition Education

“I’ve learned that I am doing what is needed to fuel my body with solid nutrition.” (P317)

“[The dietitian] help[ed] me to understand why my body reacts the way that it does when I fast or binge eat” (P265)

“I did gain more awareness of nutritional values of certain foods.” (P3)

“advising me on different things to try and what foods to avoid” (P548)

“I felt like my questions weren’t been [sic] answered fully, as I assumed they didn’t have the answers and I was just ignored or not answered at all. How can we all have the same metabolism when I’m insulin-resistant and have PCOS? … I have no answers.” (P265)

“This was the least helpful person in the office for ulcerative colitis care. There wasn’t any dietary help other than to avoid fibre completely and don’t eat foods that trigger response.” (P317)

Subtheme 1(b): Nutrition-Focused Skills

“… meal plans and guidance around portion control and recipes and ideas helps with energy in and energy out proportions” (P357)

“Helping with a meal plan that works around my numerous allergies and intolerances including Coeliac Disease, also giving ideas around portion sizes and recipes are helpful” (P83)

“It was difficult to adhere to any dietary plans for me so this … did not work for me. I find it very difficult to live the regimented lifestyle that is required by a restricted diet laid out by dietitians. I do not consider this their fault, it is mine and as such I need to take control of my lifestyle as it is apparent to me that the only person to achieve weight loss is myself.” (P43)

“Portion control [was unhelpful], because it made me want more, more hungrier.” (P549)

“Usually the dietician talks about what I eat, what I want to change, and tells me to keep a food diary. But it doesn’t really help with anything” (P51)

3.3.2. Theme 2: Person-Centred Care

Subtheme 2(a): “One Sheet Does Not Fit All”—The Importance of Individualised Treatment

“[I would have liked] To be dealt with as an individual (that is, get to know me and my issues) to tailor treatment and not just apply a 1 size fits all approach.” (P3)

“Listen to the client, if they don’t follow the textbook rulings then you need to be flexible and move away from the one sheet fits all and stop printing out the same recommendation for all patients. Sit and plan, take time to get to know what the patient requires rather than already preparing a treatment for them.” (P243)

“[I would have liked] For them to be more understanding and to realise that everyone is different. We are not all textbooks, we are all different.” (P83)

“[I would have liked] Dietary plans and meal suggestions that were able to be made at home with a family instead of being on shakes for years. These are not sustainable nor economical nor the right image for people to be portraying to teenage girls in the household. Promoting healthy eating as a family should be considered rather than individual responsibility. (P243)

“Each dietitian recommended a different type of shake, most said they were lactose free but still made me sick!“ (P207)

“[The dietitian] recommended Optifast shakes and unrealistic options for my lifestyle—like salad for lunch and shake for breakfast/dinner. Have kids.” (P513)

“the endless supply of information sheets that came with not much-perceived value.” (P3)

“dietitcian provided printouts only and general advice only” (P403)

“just given paper with recipes which made no sense to me after telling her I didn’t know how to cook” (P613)

“It was more handouts and what everyone else followed by the recommended diet menu given [and] made by them.” (P265)

“maybe someone who even wanted to be in that job. She clearly didn’t even want to be there. Just throwing papers at me” (P612)

Subtheme 2(b): Collaborative Care

“Understanding of what I am going through… Positive attitude, honest and straight to the point… Very supportive… Reassuring me that it’s ok to slip up from time to time” (P265)

“Reminder to never say never… Never give up, always start again” (P549)

“She had a weight problem she made me feel understood. She didn’t speak down to you, and asked things like, “Do you think you could try this?” She talked to me and asked me questions, didn’t just tell me to do things. And she’d say to me, “I want to know what you don’t like”. If dietitians have been around people with a weight problem (like a close friend or family) or have had a weight problem they understand more what you’re going through. She spoke to me like a friend… She shared that she had to watch what she ate as well.” (P83)

“Telling me what to do… Not helpful… Very boss[y]… Not very understanding” (P624)

“I went to the [dietitian] and wrote down everything I’d eaten and she looked at it, pushed the book towards me and said, “I’ve seen people in the hospital who eat less than you and have lost more weight than you.” (P83)

Subtheme 2(c): Continuity of Care

“Having numerous dieticians was restrictive to treatment as no consistency to continue my treatment or ongoing relationship with dietician [sic]” (P357)

“They all have something different to say, each to their own. They all have a different education background so it’s whatever avenue you want to take in the end. (P513)

“I had my surgery and the dietitian I see at the moment, I tried to ring but couldn’t get through. She rang back a week later.” (P83)

“More time with her—she went on maternity leave.” (P83)

3.3.3. Theme 3: The Roles of the Multidisciplinary Team

“They are less worried about my blood pressure and that side of things which doctors and everyone else checks. They are focused more on what will help me be healthy. You can give up cigarettes or alcohol, but you can’t give up food—understanding the difference and being supportive makes a difference.” (P548)

“I had to write down my moods as well and this made me feel understood as well.” (P83)

“It is difficult because it is a mental health problem and you need to get your head right, that’s the important part. I don’t think they could do that much different. Support in mental health would be good but I don’t know if they can.” (P548)

“Psychologist offered more helpful support regarding emotional factors” (P403)

“Seen a psychologist and they care about your background history [and] not so much what you’re eating. They’re more about self belief.” (P513)

“Private paid regular psychologist has done more than the whole irregular team at the … clinic” (P207)

“The most helpful thing I feel is the consolidation aspect of the treatment team’s message [provided by dietitian]” (P3)

“There is no follow-up. I don’t know if it’s because I’m a public patient.” (P83)

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paxton, S.J.; Hay, P.; Touyz, S.W.; Forbes, D.M.; Girolsi, F.S.; Doherty, A.; Cook, L.; Morgan, C. Paying the Price: The Economic and Social Impact of Eating Disorders in Australia; Butterfly Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- da Luz, F.Q.; Sainsbury, A.; Mannan, H.; Touyz, S.; Mitchison, D.; Hay, P. Prevalence of obesity and comorbid eating disorder behaviors in South Australia from 1995 to 2015. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralph, A.F.; Brennan, L.; Byrne, S.; Caldwell, B.; Farmer, J.; Hart, L.M.; Heruc, G.A.; Maguire, S.; Piya, M.K.; Quin, J.; et al. Management of eating disorders for people with higher weight: Clinical practice guideline. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Hay, P.; Touyz, S.; Piya, M.K. Bariatric and Cosmetic Surgery in People with Eating Disorders. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, P.; Mitchison, D.; Collado, A.E.L.; González-Chica, D.A.; Stocks, N.; Touyz, S. Burden and health-related quality of life of eating disorders, including Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), in the Australian population. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEntee, M.L.; Philip, S.R.; Phelan, S.M. Dismantling weight stigma in eating disorder treatment: Next steps for the field. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1157594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição, E.M.; Utzinger, L.M.; Pisetsky, E.M. Eating Disorders and Problematic Eating Behaviours Before and After Bariatric Surgery: Characterization, Assessment and Association with Treatment Outcomes. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2015, 23, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogg, S.; Lauretti, J.; West-Smith, L. Recommendations for the presurgical psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery patients. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016, 12, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylka, T.L.; Annunziato, R.A.; Burgard, D.; Daníelsdóttir, S.; Shuman, E.; Davis, C.; Calogero, R.M. The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: Evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, 983495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, J.L.; LeCates, A.; Ivezaj, V.; Lydecker, J.; Grilo, C.M. Internalized weight bias and loss-of-control eating following bariatric surgery. Eat. Disord. 2021, 29, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensinger, J.L.; Tylka, T.L.; Calamari, M.E. Mechanisms underlying weight status and healthcare avoidance in women: A study of weight stigma, body-related shame and guilt, and healthcare stress. Body Image 2018, 25, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, S.M.; Burgess, D.J.; Yeazel, M.W.; Hellerstedt, W.L.; Griffin, J.M.; van Ryn, M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaster, C.M.; Paxton, S.J.; Maguire, S.; Hill, A.J.; Braet, C.; Seidler, A.L.; Nicholls, D.; Garnett, S.P.; Ahern, A.L.; Wilfley, D.E.; et al. The need for future research into the assessment and monitoring of eating disorder risk in the context of obesity treatment. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Conti, J.; McMaster, C.M.; Hay, P. Beyond Refeeding: The Effect of Including a Dietitian in Eating Disorder Treatment. A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bariatric Surgery Interest Group, Dietitians Australia. Bariatric Surgery Role Statement; Dietitians Australia: Phillip, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Osland, E.; Powlesland, H.; Guthrie, T.; Lewis, C.-A.; Memon, M.A. Micronutrient management following bariatric surgery: The role of the dietitian in the postoperative period. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostecka, M.; Bojanowska, M. Problems in bariatric patient care—Challenges for dieticians. Wideochirurgia Inne Tech. Mało Inwazyjne 2017, 12, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diabetes Interest Group, Dietitians Australia. Diabetes Role Statement; Dietitians Australia: Phillip, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Noordenbos, G.; Oldenhave, A.; Muschter, J.; Terpstra, N. Characteristics and Treatment of Patients with Chronic Eating Disorders. Eat. Disord. 2002, 10, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mital, R.; Hay, P.; Conti, J.E.; Mannan, H. Associations between therapy experiences and perceived helpfulness of treatment for people with eating disorders. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piya, M.K.; Chimoriya, R.; Yu, W.; Grudzinskas, K.; Myint, K.P.; Skelsey, K.; Kormas, N.; Hay, P. Improvement in Eating Disorder Risk and Psychological Health in People with Class 3 Obesity: Effects of a Multidisciplinary Weight Management Program. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medveczky, D.M.; Kodsi, R.; Skelsey, K.; Grudzinskas, K.; Bueno, F.; Ho, V.; Kormas, N.; Piya, M.K. Class 3 Obesity in a Multidisciplinary Metabolic Weight Management Program: The Effect of Preexisting Type 2 Diabetes on 6-Month Weight Loss. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 9327910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobuch, S.; Tsang, F.; Chimoriya, R.; Gossayn, D.; O’Brien, S.; Jamal, J.; Laks, L.; Tahrani, A.; Kormas, N.; Piya, M.K. Obstructive sleep apnoea and 12-month weight loss in adults with class 3 obesity attending a multidisciplinary weight management program. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2021, 21, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gideon, N.; Hawkes, N.; Mond, J.; Saunders, R.; Tchanturia, K.; Serpell, L. Development and Psychometric Validation of the EDE-QS, a 12 Item Short Form of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prnjak, K.; Mitchison, D.; Griffiths, S.; Mond, J.; Gideon, N.; Serpell, L.; Hay, P. Further development of the 12-item EDE-QS: Identifying a cut-off for screening purposes. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, B.L.; Miller, S.D.; Sparks, J.A.; Claud, D.A.; Reynolds, L.R.; Brown, J.; Johnson, L.D. The Session Rating Scale: Preliminary psychometric properties of a “working” alliance measure. J. Brief. Ther. 2003, 3, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, Version 29.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietitians Australia. What Dietitians Do in Weight Loss Surgery. Available online: https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/sites/default/files/2023-02/Bariatric-Surgery-Role-Statement-2023.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Dietitians Australia. Diabetes Role Statement. Available online: https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/sites/default/files/2022-02/Diabetes-Role-Statement-2021.2.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Arbuckle, M.R.; Foster, F.P.; Talley, R.M.; Covell, N.H.; Essock, S.M. Applying Motivational Interviewing Strategies to Enhance Organizational Readiness and Facilitate Implementation Efforts. Qual. Manag. Health Care 2020, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, J.K.; Callahan, J.L. The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delevry, D.; Le, Q.A. Effect of Treatment Preference in Randomized Controlled Trials: Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis. Patient 2019, 12, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windle, E.; Tee, H.; Sabitova, A.; Jovanovic, N.; Priebe, S.; Carr, C. Association of Patient Treatment Preference With Dropout and Clinical Outcomes in Adult Psychosocial Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Conti, J.; McMaster, C.M.; Piya, M.K.; Hay, P. “I Need Someone to Help Me Build Up My Strength”: A Meta-Synthesis of Lived Experience Perspectives on the Role and Value of a Dietitian in Eating Disorder Treatment. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooey, M.; Bacus, C.; Ramachandran, D.; Piya, M.; Baur, L. Health service approaches to providing care for people who seek treatment for obesity: Identifying challenges and ways forward. Public Health Res. Pract. 2022, 32, e3232228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, L.M.; Granillo, M.T.; Jorm, A.F.; Paxton, S.J. Unmet need for treatment in the eating disorders: A systematic review of eating disorder specific treatment seeking among community cases. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilbert, A.; Petroff, D.; Herpertz, S.; Pietrowsky, R.; Tuschen-Caffier, B.; Vocks, S.; Schmidt, R. Meta-analysis on the long-term effectiveness of psychological and medical treatments for binge-eating disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1353–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewko, S.; Oyesegun, A.; Clow, S.; VanLeeuwen, C. High turnover in clinical dietetics: A qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, N.; Lavreysen, O.; Boone, A.; Bouman, J.; Szemik, S.; Baranski, K.; Godderis, L.; De Winter, P. Retaining Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review of Strategies for Sustaining Power in the Workplace. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, N.; Boone, A.; Godderis, L.; Bouman, J.; Szemik, S.; Matranga, D.; de Winter, P. The Race to Retain Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review on Factors that Impact Retention of Nurses and Physicians in Hospitals. Inquiry 2023, 60, 00469580231159318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Total sample | 18 |

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 33.7 ± 11.3 |

| Range: 31–67 | |

| Sex (n (%)) | |

| Female | 15 (83.3) |

| Male | 3 (16.7) |

| Ethnicity (n (%)) | |

| White | 12 (66.7) |

| Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander/Maori/Pacific Islander | 5 (27.8) |

| Relationship status (n (%)) | |

| Married/De-Facto/In a relationship | 7 (38.9) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 9 (50.0) |

| Living situations (n (%)) | |

| Alone/Shared accommodation | 6 (33.3) |

| With family | 12 (66.7) |

| Employment status ** (n (%)) | |

| Paid work (full time, part-time, or casual) | 9 (50.0) |

| Unemployed/Unemployment benefits/Pensioner | 7 (38.9) |

| Other (i.e., student, retired, parent, unpaid volunteer) | 6 (33.4) |

| Highest level of education (n (%)) | |

| Tertiary education | 16 (88.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) (n (%)) | 49.9 (12.8) |

| Range: 28.8–80.0 | |

| Eating disorder history (n (%)) | |

| Identified as having experienced eating disorder symptoms | 16 (88.9) |

| Diagnosed with an eating disorder (n = 16 *) | 8 (50) |

| Received treatment for an eating disorder (n = 16 *) | 6 (37.5) |

| Diagnosed BED ** | 5 (27.8) |

| Other ED diagnosis (i.e., ARFID, BED, SEED, OSFED, unknown) ** | 6 (33.3) |

| EDE-QS (mean ± SD) | |

| At time of survey | 20.9 ± 6.0 *** |

| Role | Saw One Dietitian (n = 4) | Saw > One Dietitian: Most Helpful (n = 14) | Saw > One Dietitian: Least Helpful (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency n (%) | |||

| Helping with meal planning | 3 (75) | 7 (50) | 11 (78.6) |

| Food diary keeping/logging | 3 (75) | 7 (50) | 6 (42.9) |

| Education about food/nutrition | 3 (75) | 9 (64.3) | 11 (78.6) |

| Dietetic counselling overlapping with aspects of ED treatment * | 1 (25) | 6 (42.9) | 4 (28.6) |

| Addressing concerns about weight ** | 0 (0) | 11 (78.6) | 10 (71.4) |

| Supportive therapy *** | 1 (0) | 6 (42.9) | 6 (42.9) |

| Other | 1 (25) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (7.1) |

| Measure | Saw One Dietitian (n = 4) | Saw > One Dietitian: Most Helpful (n = 14) | Saw > One Dietitian: Least Helpful (n = 14) | Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Z (p) | |||

| 1. When I sought this treatment, I thought change was important or possible | 76.0 (57.3) | 86.5 (18.5) | 91.0 (33.5) | −0.979 (0.328) |

| 2. The treatment approach worked well for me | 72.0 (26.5) | 43.0 (53.0) | 17.0 (51.5) | −2.223 (0.026) |

| 3. The treatment approach met my hopes and expectations | 69.5 (14.3) | 24.5 (68.5) | 16.5 (52.3) | −0.801 (0.423) |

| 4. The treatment approach assisted me in shifting my relationship with difficult emotions | 74.0 (20.8) | 21.5 (64.5) | 13.5 (43.3) | −1.274 (0.203) |

| 5. The treatment approach assisted me in recovering from the eating disorder | 65.0 (NA) ** (n = 2) | 29.0 (54.8) | 8.5 (51.5) | −1.334 (0.182) |

| 6. The treatment approach assisted me in recovering from my food/eating concerns | 64.0 (53.5) | 28.5 (50.0) | 8.5 (51.3) | −1.355 (0.176) |

| 7. The treatment approach took into consideration my treatment preferences | 55.0 (62.8) | 34.5 (69.8) | 12.0 (55.8) | −2.118 (0.034) |

| 8. The treatment approach gave me freedom to make my own choices around change | 56.0 (66.8) | 71.0 (63.8) | 27.0 (78.0) | −1.726 (0.084) |

| 9. The dietitian/nutritionist did make me feel understood | 82.5 (47.5) | 46.5 (84.25) | 13.0 (51.8) | −1.833 (0.060) |

| 10. The dietitian/nutritionist did address my concerns | 81.0 (19.3) | 55.0 (76.3) | 16.0 (41.3) | −1.538 (0.124) |

| 11. The dietitian/nutritionist did instil hope for recovery | 81.5 (14.0) | 49.0 (71.8) | 46.5 (63.5) | −1.049 (0.294) |

| 12. Overall, how helpful do you think the dietitian/nutritionist was? | 86.0 (7.3) | 27.5 (83.0) | 25.5 (54.8) | −1.328 (0.184) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Conti, J.; Piya, M.K.; McMaster, C.M.; Hay, P. One Sheet Does Not Fit All: The Dietetic Treatment Experiences of Individuals with High Eating Disorder Symptomatology Attending a Metabolic and Bariatric Clinic; an Exploratory Mixed-Methods Study. Dietetics 2024, 3, 98-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics3020009

Yang Y, Conti J, Piya MK, McMaster CM, Hay P. One Sheet Does Not Fit All: The Dietetic Treatment Experiences of Individuals with High Eating Disorder Symptomatology Attending a Metabolic and Bariatric Clinic; an Exploratory Mixed-Methods Study. Dietetics. 2024; 3(2):98-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics3020009

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yive, Janet Conti, Milan K. Piya, Caitlin M. McMaster, and Phillipa Hay. 2024. "One Sheet Does Not Fit All: The Dietetic Treatment Experiences of Individuals with High Eating Disorder Symptomatology Attending a Metabolic and Bariatric Clinic; an Exploratory Mixed-Methods Study" Dietetics 3, no. 2: 98-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics3020009

APA StyleYang, Y., Conti, J., Piya, M. K., McMaster, C. M., & Hay, P. (2024). One Sheet Does Not Fit All: The Dietetic Treatment Experiences of Individuals with High Eating Disorder Symptomatology Attending a Metabolic and Bariatric Clinic; an Exploratory Mixed-Methods Study. Dietetics, 3(2), 98-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics3020009