Highlights

1) Continuing professional education (CPE) is an important tenet of professional development and nutrition and dietetic registration.

Abstract

Lifelong learning has been integral to advancement of the nutrition and dietetics profession and its practitioners. Both the United States (US) Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR) and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (Academy) advocate for continuous skill development and professional growth. Responding to evolving environmental trends and diverse practice perspectives, the CDR joined the Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education organization in 2020, and the CDR is transforming its own continuing professional education (CPE) requirements and prior-approval program. This paper presents a historical perspective and a current state narrative review, chronicling past and recent developments in nutrition and dietetics CPE in the US, including opportunities for reflective learning and interprofessional continuing education (IPCE). Also explored are the establishment and expansion of the Joint Accreditation organization and its standards, as well as applicable case examples. Additionally, this paper outlines the CDR and the Academy’s strategies for advancing inclusion, diversity, equity, and access (IDEA) within the profession and identifies how CPE advancements may facilitate accessible and equitable CPE for an increasingly diverse membership of practitioners. Nutrition and dietetics professionals stand to benefit from a more comprehensive understanding of changes in CPE and the opportunities they may bring to the future of the profession.

1. Introduction

Lifelong learning has been a central part of the framework of the nutrition and dietetics profession since its earliest years [1]. Through the decades, the leaders of the United States (US) Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (Academy) have continued to advocate for lifelong learning as an opportunity to build individual strengths and skills and to advance the profession [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Today, the Committee for Lifelong Learning remains essential to the Academy’s governance structure [12], and lifelong learning is integral to the vision of the US Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR) [13].

Closely aligned with lifelong learning is the need for continuing professional education (CPE). Indeed, there has been a CPE requirement for dietetic credentialing from the time of the CDR’s inception over 50 years ago [1]. The nature of CPE and the CDR’s requirements have continued to evolve since then in response to environmental trends, including the need for greater accountability in demonstrating competence as well as technological innovations and diverse practice perspectives [1]. Some of the more recent changes are that the CDR has become an Associate Member organization of the Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education organization (Joint Accreditation) [14], and the CDR is now transforming its longstanding CPE provider accreditation program [15]. These modifications are occurring at the same time that the CDR is also making changes to the education requirements for becoming a registered dietitian nutritionist [16], and the Academy is working to “increase recruitment, retention, and completion of nutrition and dietetics education and leadership at all levels for underrepresented groups [17]”. Thus, in the future, there will likely be significant transformations in nutrition-related CPE offerings, as well as greater diversity in the nutrition and dietetics professionals who seek to access those offerings.

Credentialed nutrition and dietetics practitioners can benefit from a more complete understanding of the anticipated changes in the CPE landscape and their potential impacts and opportunities, yet the nutrition and dietetics literature often seems to be lacking in articles providing such a background. The objective of this narrative review is to help fill the void by presenting a context for the evolution of nutrition and dietetics CPE and opportunities to support CPE equity and accessibility in the US. Specifically, this historical perspective and current state review describes past and recent nutrition and dietetics CPE developments, including more active learning approaches like reflective learning and the movement toward interprofessional continuing education (IPCE). It also outlines the establishment and expansion of the Joint Accreditation organization, its IPCE standards, and case examples of how these standards can apply. Finally, discussed are the CDR and the Academy’s goals and strategies for building diversity in the pipeline of credentialed nutrition and dietetics practitioners and how CPE advancements may help support more accessible and equitable CPE for an increasingly diverse profession.

2. Methods

To conduct this narrative review, in the first half of 2023, we searched the nutrition and dietetics scientific literature (PubMed) and gray (Google) literature, as well as the Academy and the CDR’s publications and websites to identify content related to the basis of the US profession’s focus on lifelong learning and the subsequent development of CPE requirements, its integration of interprofessional education and active forms of learning like reflective learning, and its work to build a more diverse pipeline and address equity/expand access for CPE. We also searched the broader healthcare professional scientific literature (PubMed) and gray (Google) literature and the Joint Accreditation publications and website to chronicle the evolution of interprofessional practice and the founding and history of Joint Accreditation. Our final draft paper was reviewed by both the CDR and Joint Accreditation to confirm the historical and current state accuracy of the information presented.

3. Findings

3.1. Historical Review and Recent Advances in Nutrition and Dietetics CPE

When the CDR was first created in 1969, registration was voluntary for individuals practicing in the field of nutrition and dietetics; however CPE was required to maintain registration [1]. Similarly, the need for CPE aligned with the profession’s education goals at the time, which included “ongoing continuing education and development throughout the lifetime of each dietitian [18]”.

Stein and Rops [1] described how, through the decades, the CDR’s approach to CPE has continued to advance. A 1984 Study Commission on Dietetics report envisioned “a new and greater role for continuing education in dietetics” and the need for “formal identification, preparation, and presentation of recurring programs planned specifically to meet the needs of individual dietitians [19]”. This report helped provide an impetus in the early 1990s for the CDR’s introduction of a Self-Assessment Series for Dietetics Professionals: An Approach to Continuing Professional Education, which was based on simulated practice scenarios. Later, these programs evolved with technology into the CDR’s online Assess and Learn modules.

By the mid-1990s, there was an increased emphasis within healthcare on the need for greater professional accountability and growing support for the view that simply documenting CPE units was insufficient to demonstrate competence. Aligning with other professions in response, the CDR launched its Professional Development Portfolio (PDP) process in 2001 [1]. The PDP’s underlying principle is that effective CPE involves “more than information transfer alone”; and thus, the PDP helps guide practitioners in identifying their own learning goals and needs and verifying their completion of related CPE [20]. The CDR has further refined the PDP process over the last 10 years to base it on essential and validated practice competencies; practice competencies help to “identify learning needs” and “guide continuing professional development and ongoing competence [21]”.

Self-reflection is a fundamental part of the PDP process. Indeed, the CDR’s Professional Development Portfolio Guide defines a “consciously competent practitioner” as one who “reflects on their practice, identifies learning needs, and selects resources and tools that help to address learning needs and demonstrate competence”. The guide specifically includes reflection in Step 3: The Professional Development Self-Assessment [22]. Reflection is also a form of active learning that can yield multiple benefits, including increased learning from an experience and deeper rather than superficial learning [23]. When reflective learning is used in CPE, it can be more effective than other forms of learning, such as the traditional lecture-based approach [24].

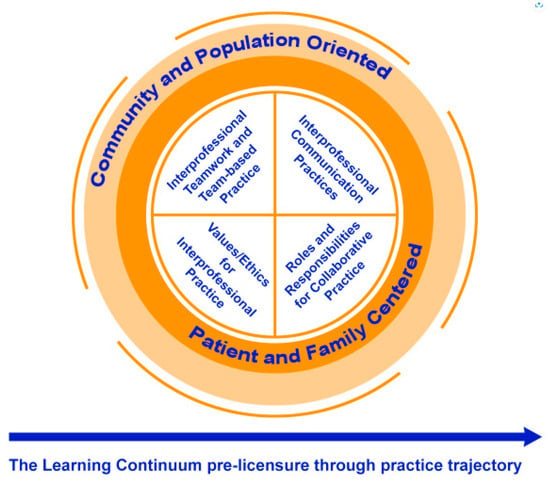

Facilitated self-reflection using learning portfolios can also be helpful in strengthening competencies for interprofessional practice. The World Health Organization defines interprofessional education as occurring when “two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes [25]”. Interprofessional team-based care is critical for the delivery of safe, high-quality healthcare [26]. The core competencies of interprofessional practice required are those related to values, roles, teamwork, and communication (Figure 1) [27], and the IPCE field is developing and advancing to build these competencies among healthcare professionals [28].

Figure 1.

Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice [27].

Interprofessional education has also become a part of healthcare professionals’ education standards and requirements. For example, the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics (ACEND) mandates the inclusion of interprofessional education in nutrition and dietetics curricula [29]. In addition, the CDR joined as a member organization of Joint Accreditation in 2020, and 5-year CDR nutrition and dietetics recertification requirements can now be met via an IPCE credit offered by joint-accredited providers. Another change is that the CDR will no longer accredit CPE providers, starting in 2024 [15]. The CDR has also updated its standards for the prior approval of nutrition and dietetics CPE. The CDR’s new policies for the prior approval of nutrition and dietetics CPE were released in the summer of 2023 and will take effect in April 2024; the policies are similar but not identical to Joint Accreditation’s IPCE standards. As an example, provider eligibility for the CDR’s prior approval program is unrestricted by the type or location of a business organization [30], whereas Joint Accreditation follows the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) Standards for Integrity and Independence, which prohibit the eligibility of companies whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, re-selling, or distributing healthcare products used by or on patients (i.e., ineligible companies) [31].

The CDR’s new processes will require additional evaluation and documentation as well. CPE providers will be required to gather detailed data for an initial benchmarking report and then an annual report which will include reporting on the promotion of inclusion, diversity, equity, and access (IDEA); quality improvement processes; commercial support and funding; and the identification of and addressing practice gaps. Participants will be offered an opportunity to evaluate CPE activities using specific required evaluation components [30]. Throughout the execution of these CDR revisions, it is essential that CPE providers be prepared to meet the requirements while still maintaining their efficiencies and accuracies in CPE program development.

| Practice Point: The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ focus on lifelong learning and the framework of the Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR) for continuing professional education (CPE) have continued to evolve and advance. Self-reflection is fundamental to the nutrition and dietetics professional development process, and a reflective learning approach can yield increased and deeper learning. Interprofessional practice benefits high-quality care delivery and interprofessional continuing education (IPCE) can fulfill the CDR’s recertification requirements. |

3.2. Review of the Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education’s Development and IPCE Standards

With the CDR joining Joint Accreditation and some CPE providers now pursuing joint accreditation as a way to continue offering accredited nutrition CPE, it can be helpful for credentialed nutrition and dietetics practitioners to better understand Joint Accreditation and its standards. Joint Accreditation was cofounded in 2009 by three healthcare-accrediting organizations, ACCME, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) (Supplementary Table S1) [32]. Its mission is to support IPCE [33,34]. Joint Accreditation accredited the first organizations in 2010. Joint Accreditation is the first continuing education collaboration between healthcare organization bodies to offer IPCE [35].

Today, Joint Accreditation has grown to incorporate 10 accrediting healthcare organizations, including the CDR, the American Academy of Physician Associates, the American Dental Association’s Continuing Education Recognition Program, the American Psychological Association, the Association of Social Work Boards, the Association of Regulatory Boards of Optometry’s Council on Optometric Practitioner Education (ARBO/COPE), and the Board of Certification for the Athletic Trainer [36]. In addition, Joint Accreditation includes more than 150 accredited provider organizations. Together, Joint Accreditation members offer nearly 100,000 educational activities annually to support over 28 million interactions with healthcare professionals, and these numbers continue to grow [36]. For IPCE to continue to become successfully integrated, it must be part of lifelong learning and implemented collaboratively by healthcare professionals and their organizations [33].

As an accrediting organization, Joint Accreditation provides a single, unified application process that includes a fee structure and set of IPCE accreditation standards, including commendation [35]. IPCE supports improved healthcare delivery, better patient outcomes, and learning opportunities that promote interprofessional collaborative practice. The benefits joint-accredited organizations receive in offering IPCE include alignment between accreditation standards and the ability to offer continuing education for up to 10 different professions without having to undertake separate accreditation processes for each individual profession [33].

To become joint-accredited, organizations must meet the following criteria:

- The organization’s education structure and processes were designed by and for the healthcare team and have been in place for at least the past 18 months;

- At least 25% of all the educational activities delivered by the organization during the past 18 months were interprofessional, and the organization can demonstrate an integrated planning process (i.e., the process includes input from two or more health professions who represent the targeted healthcare team to address identified practice gaps);

- The organization engages in the joint-accreditation process, demonstrates compliance with the Joint Accreditation Criteria (JAC), [37] and is in good standing if currently accredited by any of Joint Accreditation’s collaborating accreditors [38].

In addition to the Joint Accreditation Criteria, jointly accredited provider organizations must develop their activities to comply with the ACCME Standards for Integrity and Independence in Accredited Continuing Education [31]. Table 1 provides case examples, applications, and exceptions for these ACCME standards [31] and Table 1 also includes related policies for the CDR’s new prior approval program, which was released in 2023 [30].

Table 1.

Case examples, applications, and exceptions for the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) Standards for Integrity and Independence in Accredited Continuing Education [31] and related policies for the Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR) prior approval program for nutrition and dietetics continuing professional education [30].

Throughout Joint Accreditation’s development, there have been many learnings and opportunities to streamline processes while ensuring that the individual requirements for all accrediting bodies are met [34]. Further, various accrediting organizations have shared their experiences, lessons learned, and best practices as they have become joint-accredited and begun offering IPCE. For example, after the Council on Optometric Practitioner Education (COPE) introduced IPCE, it witnessed improved communication, the opportunity for optometrists to learn with other professionals, advances in the quality and integrity of healthcare education, greater visibility and credibility for COPE among other providers of healthcare CPE, an ability for COPE to reach more healthcare professionals, and expanded CPE offerings for optometrists both nationally and internationally [33].

The path for healthcare-accrediting organizations to develop IPCE has been well-documented by others, such as when the ANCC endorsed and adopted the Standards for Integrity and Influence into their own credentialing program by providing a transition plan to ensure that the standards were integrated [39]. Further, Joint Accreditation has identified specific principles for planning IPCE activities. Specifically, “the planning process for educational activities classified as interprofessional must demonstrate:

- An integrated planning process that includes healthcare professionals from two or more professions.

- An integrated planning process that includes healthcare professionals who are reflective of the target audience members the activity is designed to address.

- An intent to achieve outcome(s) that reflect a change in skills, strategy, or performance of the healthcare team and/or patient outcomes.

- Reflection of one or more of the interprofessional competencies to include values/ethics, roles/responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and/or teams/teamwork.

- An opportunity for learners to learn with, from, and about each other.

- Activity evaluations that seek to determine:

- ○

- Changes in skills, strategy, performance of one’s role or contribution as a member of the healthcare team; and/or

- ○

- Impact on the healthcare team; and/or

- ○

- Impact on patient outcomes [32]”.

IPCE itself has been documented to have a positive impact on patient outcomes and team-based care [40]. Joint Accreditation reports that various healthcare-accrediting bodies coming together as one has increased diversity in healthcare providers’ perspectives on education offerings, the type of education offered, and the recognition and support of team-based care to ensure the best patient care is provided [41]. In summary, Joint Accreditation provides the framework necessary to uphold JAC standards, ensure that IPCE is integrated successfully within healthcare professionals’ education and their organizations, and support team-based care to ensure quality care for patients and communities.

| Practice Point: In 2020, the Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR) joined the Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education organization (Joint Accreditation). Joint-accredited organizations have the advantage of being able to offer interprofessional continuing education (ICPE) for up to 10 different professions. To become joint-accredited, organizations must meet specific criteria, including that their ICPE complies with the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) Standards for Integrity and Independence in Accredited Continuing Education. |

3.3. Current State Review of the CDR and Academy’s Strategies for Building a More Diverse Practitioner Pipeline and Opportunities to Support CPE Access and Equity

Joint Accreditation also presents a forum for critical conversations on how to address the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, and access (IDEA) in IPCE programming and professional development [42]. This could benefit the CDR, which has its own goal of fostering inclusive learning in CPE, and the Academy with respect to overcoming IDEA barriers within the profession. Agic et al. [43] identified that CPE can be a “critical driver of change to improve quality of care, health inequities, and system change”, further explaining that to address healthcare disparities, CPE must first address equity and inclusion issues in education development and delivery. It is opportune, then, that for the first time, the CDR’s new prior-approval program policies integrate IDEA into nutrition CPE offerings and activities. Specifically, the new CDR policies state that each prior-approved CPE activity should be conducted with a comprehensive IDEA lens, and the policies further specify how this should be applied by providers [30]. Such policies align with the definition and standards of other healthcare professional organizations who are members of Joint Accreditation, including the American Psychological Association, which states that sponsors providing CPE must both select instructors and develop program content that respects cultural, individual, and role differences, including those based on age, gender, gender identity, race, ethnicity, culture, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, disability, language, and socioeconomic status [44].

The integration of IDEA is a new consideration that will advance the development of nutrition and dietetics CPE and the profession, as well as help reduce health disparities. As the population in the US becomes more diverse, both racially and ethnically [45], it is critical that efforts related to CPE development and recruitment for the profession continue to foster IDEA with intentionality. Acknowledging that a more diverse dietetic professional workforce would better serve health-disparate communities of color, the Academy is taking a strategic lead in this area [17]. The Academy recognizes that increasing the diversity of the profession and expanding its reach to areas with limited care access will (1) ensure more equitable care for everyone, (2) enhance cultural competency and the ability to provide practical medical nutrition therapy and nutrition education that are relevant to patients’ needs, (3) improve access to higher-quality care that is more culturally relevant for the medically underserved, (4) promote health equity and the diversity of lived experience, and (5) increase opportunities for more diverse populations in nutrition research studies.

A heightened national interest in increasing healthcare professional diversity—particularly among those supporting access to food and nutrition and related healthcare services—prompted the inclusion in the 2022 White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health National Strategy of specific recommendations for strengthening and diversifying the nutrition workforce [46]. The Academy submitted comments that helped inform these recommendations; specifically, the Academy’s National Organization of Blacks in Dietetics and Nutrition (NOBIDAN) member interest group played an instrumental role in submitting comments that brought attention to the need for more support of dietetic programs in historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

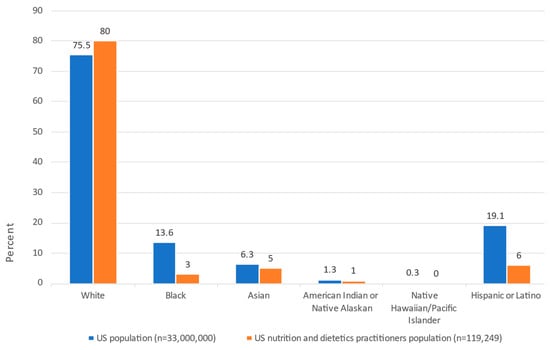

Traditionally, successful diversity strategies for change have been slow to evolve in nutrition and dietetics and therefore, the profession still does not necessarily represent the communities it serves. Taub-Dix [47], a White dietitian, writes “Whether obvious or subtle, racial inequality and exclusion—and therefore a lack of diversity—always has existed in the dietetics profession”. This is reflected in a simple comparison of the racial and ethnic mix of the US population to the population of US nutrition and dietetics professionals (Figure 2) [48,49]. Indeed, the demography of Hispanic or Latino and Black Americans remains starkly underrepresented in the nutrition and dietetics profession, even as these same groups have the highest morbidity and mortality rates from chronic conditions that are frequently diet-related [50].

Figure 2.

Comparison of the race and ethnicity of the US population [48] and of practicing registered dietitian nutritionists and nutrition and dietetics technicians, registered [49].

In 2011, the Academy (then the American Dietetic Association) released a practice paper showing the ways in which food and nutrition professionals could influence the elimination of racial and ethnic health disparities [51]. Using the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations [52] the practice paper targeted all areas of registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) practice for change, including clinical, food manufacturing and food service, public health and community nutrition, and education and research. In addition, the practice paper recognized the importance of considering those with disabilities and other groups experiencing biases due to gender and sexual orientation.

Multiple attempts have since been made to create an educational pipeline to increase diversity in the profession [53,54]. The CDR’s vision and the Academy’s Strategic Plan principles recognize the importance of supporting practitioner diversity and amplifying the contribution and value of diverse nutrition and dietetics practitioners [13,55]. More significant and intentional activities include the Academy establishing a very comprehensive and inclusive website of resources. The website highlights the Academy’s commitment to a no-tolerance position on any instances of inequity or discrimination in any of its nutrition and dietetics education programs; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation diversity scholarships supported and funded by the CDR; IDEA mini grants, mentoring opportunities like the Research, International, and Scientific Affairs (RISA) team mentorship for underrepresented minorities in research; ACEND 2022 diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) standards for dietetic education programs; a comprehensive series of DEI webinars, articles, and books; and website links [17].

Academy member interest groups (MIGs) represent an additional successful strategy for increasing diversity in the nutrition and dietetics profession and supporting more inclusive CPE. The MIGs offer Academy members opportunities to join, mentor, and connect with individuals of common interests, issues, backgrounds and/or abilities regardless of practice area, and many MIGs provide CPE. In addition, the MIGs reflect the diversity of the Academy itself, as well as the communities it serves. Importantly, Stein [53] identified that the successes of the Academy may be related to increasing the “space for people to connect around shared identity and relatedness”.

New education requirements represent another area in which there may be growth in IDEA. As of January 2024, students pursuing RDN exam eligibility will need a minimum of a graduate degree granted by a US Department of Education-recognized institution (or a foreign equivalent) [56]. Many Master’s of Science-level dietetic education programs are already beginning to see a broader pool of new students with various undergraduate degrees. A number of these students are entering the profession as a second career, are older, and are bringing with them the diversity of their learned and lived experiences. Increasing Individualized Supervised Practice Pathway (ISPP) programs for Didactic Programs in Dietetics (DPDs) and Doctorate programs will open opportunities for students who were not accepted into traditional dietetic internships and increase the diversity of education and training experiences for the profession. Critical to successfully institutionalizing these new pathways and incentivizing a more diverse pipeline of students are sustained scholarships and funding from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation (which offers a number of scholarships for underrepresented groups) [57], not-for-profit organizations with an interest in nutrition, corporations, and the government (including the White House and other federal and state initiatives). The future looks very promising for new students entering the profession and the diversity of education, perspectives, heritage, and lived experiences they will bring to the profession.

The challenge will be for CPE providers to offer nutrition CPE and IPCE programs that appeal to this more diverse group of nutrition and dietetics professionals. One opportunity is the use of digital platforms that are artificial-intelligence-driven for reflective learning to support these needs and equitable access [58]. With the CDR joining the ranks of other healthcare-professional organizations that hold membership in Joint Accreditation, there is also potential to leverage other organizations’ strategies for IDEA in IPCE and create learning environments in which “each learner’s input is heard and valued” and the entire team is engaged [36].

| Practice Point: As the US population becomes more diverse, it is critical that nutrition and dietetics recruitment and continuing professional education (CPE) continue to intentionally foster inclusion, diversity, equity, and access (IDEA). The new policies of the Commission on Dietetics Registration (CDR) require prior-approved CPE activities to be conducted with a comprehensive IDEA lens. These steps are important to advance the nutrition and dietetics profession and the development of CPE, as well as to help reduce health disparities. |

4. Conclusions

CPE is an important tenet of professional development and nutrition and dietetic registration. As outlined in this narrative review, historically, the emphasis of nutrition CPE has been on the role of the nutrition and dietetics professional. However, today’s CPE needs an increased focus on interprofessional education too and its benefits for healthcare teams and quality care outcomes. There is also a greater need for CPE that reflects more diverse, equitable, and inclusive perspectives from development to delivery.

The CDR has a pivotal role to play in this transformation, particularly as it shares Joint Accreditation’s philosophy and vision for high-quality CPE. The CDR’s joining Joint Accreditation and acceptance of IPCE for maintaining registration credentials are important steps forward. When joint-accredited providers produce nutrition-specific IPCE, they must ensure that it is developed through an integrated planning process involving two or more health professions. This creates an opportunity to demonstrate and reinforce to other healthcare professionals the value of quality nutrition care and the role of credentialed nutrition and dietetics practitioners.

Developing CPE that supports IDEA principles is critical both now and in the future. The CDR and Joint Accreditation have each included IDEA guidance in their policies for CPE program providers. Ultimately, it is credentialed nutrition and dietetics practitioners in the US who will benefit from these CPE changes that integrate new and innovative approaches and empower the profession to promote and increase a diverse culture of collaboration, alignment, and positive engagement.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/dietetics2040023/s1, Table S1: Development timeline for Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing, and reviewing: A.L.G., P.A.L., B.D. and M.B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the US Commission on Dietetic Registration and the Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education organization for their review of the historical and current state accuracy of the information presented.

Conflicts of Interest

A.L.G. and M.B.A. are employees and shareholders of Abbott. B.D. is the President of Becky Dorner & Associates. P.A.L. has no conflict of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

| AAPA | American Academy of Physician Associates |

| Academy | Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics |

| ACCME | Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education |

| ACEND | Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics |

| ACPE | Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education |

| ADA CERP | American Dental Association’s Continuing Education Recognition Program |

| ANCC | American Nurses Credentialing Center |

| APA | American Psychological Association |

| ARBO | Association of Regulatory Boards of Optometry |

| ASWB | Association of Social Work Boards |

| BOC | Board of Certification for the Athletic Trainer |

| CDR | Commission on Dietetic Registration |

| COPE | Council on Optometric Practitioner Education |

| CPE | Continuing Professional Education |

| DEI | diversity, equity, and inclusion |

| DPD | Didactic Program in Dietetics |

| HBCUs | historically Black colleges and universities |

| IDEA | inclusion, diversity, equity, and access |

| IPCE | interprofessional continuing education |

| ISPP | Individualized Supervised Practice Pathway |

| JAC | Joint Accreditation Criteria |

| Joint Accreditation | Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education |

| MIG | Member Interest Group |

| NOBIDAN | National Organization of Blacks in Dietetics and Nutrition |

| PDP | Professional Development Portfolio |

| RISA | Research, International, and Scientific Affairs |

| RDN | registered dietitian nutritionist |

| US | United States |

References

- Stein, K.; Rops, M. The Commission on Dietetic Registration: Ahead of the trends for a competent 21st century workforce. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1981–1997.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernoff, R. President’s page: A little knowledge. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1996, 96, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puckett, R.P. Education and the dietetics profession. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1997, 97, 252–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitz, P. President’s Page: Lifelong learning is the key to success. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 1997, 97, 1014. [Google Scholar]

- Monsen, E.R. Lifelong learning expands career horizons. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1999, 99, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsen, E.R. Becoming an active learner--and teacher--for life. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000, 100, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touger-Decker, R. Developing a continuum for lifelong learning in dietetics. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbride, J.A. The challenges and rewards of life-long learning. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadrick, M.M. Accountability for lifelong learning. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, E.A. Lifelong learning advances us—One and all. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyff, R.L. The Value of lifelong learning: Key element in professional career development. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 1999, 99, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Eat Right Pro: Committee for Lifelong Learning. Available online: https://www.eatrightpro.org/leadership/governance/academy-committees/committee-for-lifelong-learning (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Commission on Dietetic Registration. About CDR. Available online: https://www.cdrnet.org/about (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Joint Accreditation Interprofessional Continuing Education. Commission on Dietetic Registration Joins Joint Accreditation. Available online: https://jointaccreditation.org/news/commission-dietetic-registration-joins-joint-accreditation/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Commission on Dietetic Registration. Credentialing Tips: Phase-Out-CDR CPE Accredited Provider Program. Available online: https://admin.cdrnet.org/vault/2459/web/Credentialing%20Tips-Phase-Out-CDR%20CPE%20Accredited%20Provider%20Program%20Feb%202022.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Shanley, E.R. Recruiting and preparing the next generation of practitioners. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 2203–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Eat Right Pro: Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access. Available online: https://www.eatrightpro.org/about-us/our-work/inclusion-diversity-equity-and-access (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Goals of the Lifetime Education of the Dietitian. Committee on Goals of Education for Dietetics, Dietetic Internship Council, the American Dietetic Association. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1969, 54, 91–93. [CrossRef]

- American Dietetic Association. A new look at the profession of dietetics. Final report of the American Dietetic Association Foundation 1984 Study Commission on Dietetics: Summary and recommendations. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1984, 84, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission on Dietetic Registration. Professional Development Portfolio Guide with Essential Practice Competencies. 2018. Available online: https://www.cdrnet.org/vault/2459/web/files/PDP%20Guide%202018.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Worsfold, L.; Grant, B.L.; Barnhill, G.C. The essential practice competencies for the Commission on Dietetic Registration’s credentialed nutrition and dietetics practitioners. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission on Dietetic Registration. Professional Development Portfolio Guide with Essential Practice Competencies. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdrnet.org/vault/2459/web/CDR%20PDP%20Guide%20June%202%202023%20thru%20May%202029_v2_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Davies, S. Embracing reflective practice. Educ. Prim. Care 2012, 23, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragkos, K.C. Reflective practice in healthcare education: An umbrella review. Educ. Sci. 2016, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative-practice (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Continuing Education, Professional Development, and Lifelong Learning for the 21st Century Health Care Workforce. Available online: https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/community-based-linkages/reports/eleventh-2011.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- The University of Texas Austin Center for Health Interprofessional Practice and Education. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice. Available online: https://healthipe.utexas.edu/core-competencies-interprofessional-collaborative-practice-0 (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Regnier, K.; Chappell, K.; Travlos, D.V. The role and rise of interprofessional continuing education. J. Med. Regul. 2019, 105, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.; Weeden, A. The interprofessional practice learning needs of nutrition and dietetics students. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 123, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission on Dietetic Registration. CDR CPEU Prior Approval Program Provider Policy Manual. Available online: https://www.cdrnet.org/vault/2459/web/CDR%20CPEU%20Prior%20Approval%20Program%20Provider%20Policy%20Manual.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. Standards for Integrity and Independence in Accredited Continuing Education Released December 2020. Available online: https://accme.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/884_20210624_New%20Standards%20Standalone%20Package.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Joint Accreditation Interprofessional Continuing Education. Joint Accreditation Framework Advancing Healthcare Education by the Team, for the Team. Available online: https://jointaccreditation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/816_20230130_ja_framework.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Regnier, K.; Travlos, D.V.; Pace, D.; Powell, S.; Hunt, A. Leading change together: Supporting collaborative practice through Joint Accreditation for Interprofessional Continuing Education. J. Eur. CME 2022, 11, 2146372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, K.; Regnier, K.; Travlos, D.V. Leading by example: The role of accreditors in promoting interprofessional collaborative practice. J. Interprof. Care 2018, 32, 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint Accreditation Interprofessional Continuing Education. Accrediting Organizations for ICPE for Healthcare. Available online: https://jointaccreditation.org/joint-accreditation/accrediting-organizations/ (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Joint Accreditation Interprofessional Continuing Education. 2022 Joint Accreditation Data Report: Touchstones of Strength and Progress in Accredited Continuing Education for Healthcare Teams. Available online: www.jointaccreditation.org/reports/2022-data-report (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Joint Accreditation Interprofessional Continuing Education. Joint Accreditation Criteria. Available online: https://jointaccreditation.org/accreditation-process/requirements/criteria/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Joint Accreditation Interprofessional Continuing Education. Accreditation Process Eligibility. Available online: https://jointaccreditation.org/accreditation-process/eligibility/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Moulton, J.; Dickerson, P. Implementing the standards for integrity and independence in accredited nursing continuing professional development. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2022, 53, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.; Arndt, R.; Katz, A.R.; Loos, J.R.; Masaki, K.; Tokumaru, S.; Davis, K.F. Transforming the future of health care today with interprofessional education. Hawaii J. Health Soc. Welf. 2023, 82, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Accreditation Interprofessional Continuing Education. Improving Healthcare with Interprofessional Continuing Education (IPCE). Available online: https://jointaccreditation.org/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Joint Accreditation Interprofessional Continuing Education. 2022 Joint Accreditation Leadership Summit Climbing Higher with IPCE. Available online: https://jointaccreditation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2022-Joint-Accreditation-Leadership-Summit_Climbing-Higher-with-IPCE.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Agic, B.; Fruitman, H.; Maharaj, A.; Taylor, J.; Ashraf, A.; Henderson, J.; Ronda, N.; McKenzie, K.; Soklaridis, S.; Sockalingam, S. Advancing curriculum development and design in health professions education: A health equity and inclusion framework for education programs. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. What Does Diversity Mean as an Approved Sponsor? Available online: https://www.apa.org/ed/sponsor/resources/diversity.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- U.S. Census Bureau. The Chance That Two People Chosen at Random Are of Different Race or Ethnicity Groups Has Increased Since. 2010. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/2020-united-states-population-more-racially-ethnically-diverse-than-2010.html (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Biden-Harris Administration National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition and Health. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/White-House-National-Strategy-on-Hunger-Nutrition-and-Health-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Taub-Dix, B. Diversifying Dietetics. Todays Dietit. 2020, 22, 4. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045222 (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Rogers, D. Report on the Academy/Commission on Dietetic Registration 2020 Needs Satisfaction Survey. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, R.V.; Smith, F. Black and Hispanic Americans at Higher Risk of Hypertension, Diabetes, Obesity: Time to Fix Our Broken Food System. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/black-and-hispanic-americans-at-higher-risk-of-hypertension-diabetes-obesity-time-to-fix-our-broken-food-system/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Johnson-Askew, W.L.; Gordon, L.; Sockalingam, S. Practice paper of the American Dietetic Association: Addressing racial and ethnic health disparities. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Smedley, B.D., Stith, A.Y., Nelson, A.R., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, K. The Educational pipeline and diversity in dietetics. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, S13–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, K.G.; Delgado, K.; Chen, M.; Paul, R. Strategies and recommendations to increase diversity in dietetics. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Eat Right Pro: Academy Strategic Plan. Available online: https://www.eatrightpro.org/about-us/our-work/academy-strategic-plan (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Commission on Dietetic Registration. 2024 Graduate Degree Requirement-Registration Eligibility. Available online: https://www.cdrnet.org/graduatedegree (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Eat Right Pro: Academy Foundation Accepting Scholarship Applications. Available online: https://www.eatrightpro.org/about-us/for-media/press-releases/academy-foundation-accepting-scholarship-applications (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Cohen, B.; DuBois, S.; Lynch, P.A.; Swami, N.; Noftle, K.; Arensberg, M.B. Use of an artificial intelligence-driven digital platform for reflective learning to support continuing medical and professional education and opportunities for interprofessional education and equitable access. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).