Coherent Neutrino Scattering and Quenching Factor Measurement †

Abstract

1. Introduction

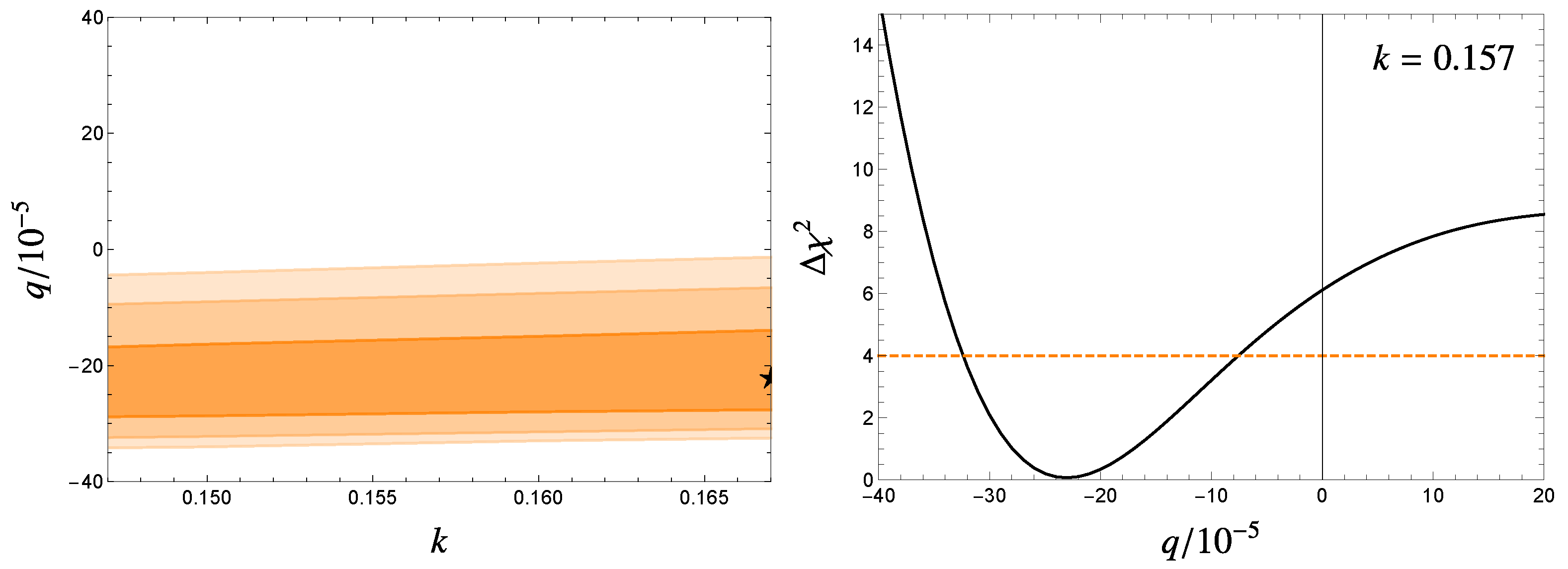

2. CENS

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freedman, D.Z. Coherent neutrino nucleus scattering as a probe of the weak neutral current. Phys. Rev. D 1974, 9, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimov, D.; Albert, J.B.; An, P.; Awe, C.; Barbeau, P.S.; Becker, B.; Belov, V.; Brown, A.; Bolozdynya, A.; Cabrera-Palmer, B.; et al. Observation of coherent elastic neutrino-nucleus scattering. Science 2017, 357, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimov, D.; Albert, J.B.; An, P.; Awe, C.; Barbeau, P.S.; Becker, B.; Belov, V.; Bernardi, I.; Blackston, M.A.; Blokl, L.; et al. First Measurement of Coherent Elastic Neutrino-Nucleus Scattering on Argon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papoulias, D.K.; Kosmas, T.S.; Kuno, Y. Recent probes of standard and non-standard neutrino physics with nuclei. Front. Phys. 2019, 7, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Arevalo, A.; Bertou, X.; Bonifazi, C.; Cancelo, G.; Castañeda, A.; Vergara, B.C.; Chavez, C.; D’Olivo, J.C.; Dos Anjos, J.C.; Estrada, J.; et al. Exploring low-energy neutrino physics with the Coherent Neutrino Nucleus Interaction Experiment. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 092005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet, H.; Bonhomme, A.; Buck, C.; Fülber, K.; Hakenmüller, J.; Heusser, G.; Hugle, T.; Lindner, M.; Maneschg, W.; Rink, T.; et al. Constraints on Elastic Neutrino Nucleus Scattering in the Fully Coherent Regime from the CONUS Experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 041804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colaresi, J.; Collar, J.I.; Hossbach, T.W.; Kavner, A.R.L.; Lewis, C.M.; Robinson, A.E.; Yocum, K.M. First results from a search for coherent elastic neutrino-nucleus scattering at a reactor site. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 072003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaresi, J.; Collar, J.I.; Hossbach, T.W.; Lewis, C.M.; Yocum, K.M. Suggestive evidence for coherent elastic neutrino-nucleus scattering from reactor antineutrinos. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.09672. [Google Scholar]

- Collar, J.I.; Kavner, A.R.L.; Lewis, C.M. Germanium response to sub-keV nuclear recoils: A multipronged experimental characterization. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 103, 122003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.R.; Nystrand, J. Interference in exclusive vector meson production in heavy ion collisions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 2330–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, D.A.; Liao, J.; Marfatia, D. Impact of form factor uncertainties on interpretations of coherent elastic neutrino-nucleus scattering data. J. High Energy Phys. 2019, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhard, J.; Nielsen, V.; Scharff, M.; Thomsen, P. Integral equations governing radiation effects. Kgl. Danske Videnskab. Selskab. Mat. Fys. Medd. 1963, 33, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.T.; Li, H.B.; Li, X.; Lin, S.K.; Wong, H.T.; Deniz, M.; Fang, B.B.; He, D.; Li, J.; Lin, C.W.; et al. New limits on spin-independent and spin-dependent couplings of low-mass WIMP dark matter with a germanium detector at a threshold of 220 eV. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 061101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, J.D.; Smith, P.F. Review of mathematics, numerical factors, and corrections for dark matter experiments based on elastic nuclear recoil. Astropart. Phys. 1996, 6, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhard, J.; Scharff, M.; Schiott, H.E. Range concepts and heavy ion ranges. Mat. Fys. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. 1963, 33, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, P. Atomic limits in the search for galactic dark matter. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 083509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Liu, H.; Marfatia, D. Coherent neutrino scattering and the Migdal effect on the quenching factor. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Liu, H.; Marfatia, D. Implications of the first evidence for coherent elastic scattering of reactor neutrinos. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 106, L031702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beda, A.; Brudanin, V.; Egorov, V.; Medvedev, D.; Pogosov, V.; Shirchenko, M.; Starostin, A. The results of search for the neutrino magnetic moment in GEMMA experiment. Adv. High Energy Phys. 2012, 2012, 350150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenarios | k | /dof | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SM w/standard Lindhard | 0 | 14.34/19 | |

| SM w/modifed Lindhard w/fixed k | 8.28/18 | ||

| SM w/modified Lindhard w/ | 8.14/17 | ||

| light w/ MeV, | 0 | 9.09/17 | |

| light scalar w/ MeV, | 0 | 7.77/17 | |

| neutrino magnetic moment w/ | 0 | 11.71/18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, J. Coherent Neutrino Scattering and Quenching Factor Measurement. Phys. Sci. Forum 2023, 8, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/psf2023008018

Liao J. Coherent Neutrino Scattering and Quenching Factor Measurement. Physical Sciences Forum. 2023; 8(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/psf2023008018

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Jiajun. 2023. "Coherent Neutrino Scattering and Quenching Factor Measurement" Physical Sciences Forum 8, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/psf2023008018

APA StyleLiao, J. (2023). Coherent Neutrino Scattering and Quenching Factor Measurement. Physical Sciences Forum, 8(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/psf2023008018