1. Introduction

Global seafood intake has risen markedly over the past decades, reaching approximately 20 kg per capita in 2019, nearly twice the level reported in the 1960s [

1]. Seafood is a key contributor to global nutrition, supplying high-quality protein and omega-3 fatty acids, and remains fundamental to food security. Yet, rising consumption has been accompanied by increasing concern over chemical contamination, particularly heavy metals. Numerous recent studies and media reports have documented the presence of mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and arsenic (As) across a wide range of seafood species. These toxic elements enter aquatic systems through industrial emissions, mining effluents, and other pollution sources, subsequently bioaccumulating through marine food webs and posing health risks to consumers [

2]. Heavy metals are environmentally persistent and resist degradation, leading them to progressively accumulate in the tissues of fish and shellfish over time [

3]. Chronic dietary exposure to heavy metals is associated with a range of severe health outcomes. For example, methylmercury from fish is a well-established neurotoxin that impairs brain development; lead contributes to neurological and developmental disorders; cadmium induces renal and skeletal damage; and inorganic arsenic is a recognized carcinogen linked to skin lesions and multiple cancer types [

2].

In recent years, research has increasingly focused on

post-mortem processing technologies capable of reducing heavy metals through targeted physicochemical mechanisms. These interventions operate directly on harvested seafood, using controlled leaching, thermal disruption, ligand-mediated complexation, or engineered separation processes to mobilize or extract toxic elements from edible tissues. Unlike pre-harvest strategies such as aquaculture management or environmental remediation, these approaches provide practical, scalable solutions that can be applied irrespective of the contamination source, thereby enhancing the safety of seafood entering the supply chain. A wide range of chemical and physical interventions have been investigated, including immersion of seafood tissues in solutions containing ligands capable of selectively complexing metal ions, the use of food-grade processing aids that enhance metal extraction [

4] and the application of emerging technologies such as electrochemical separation.

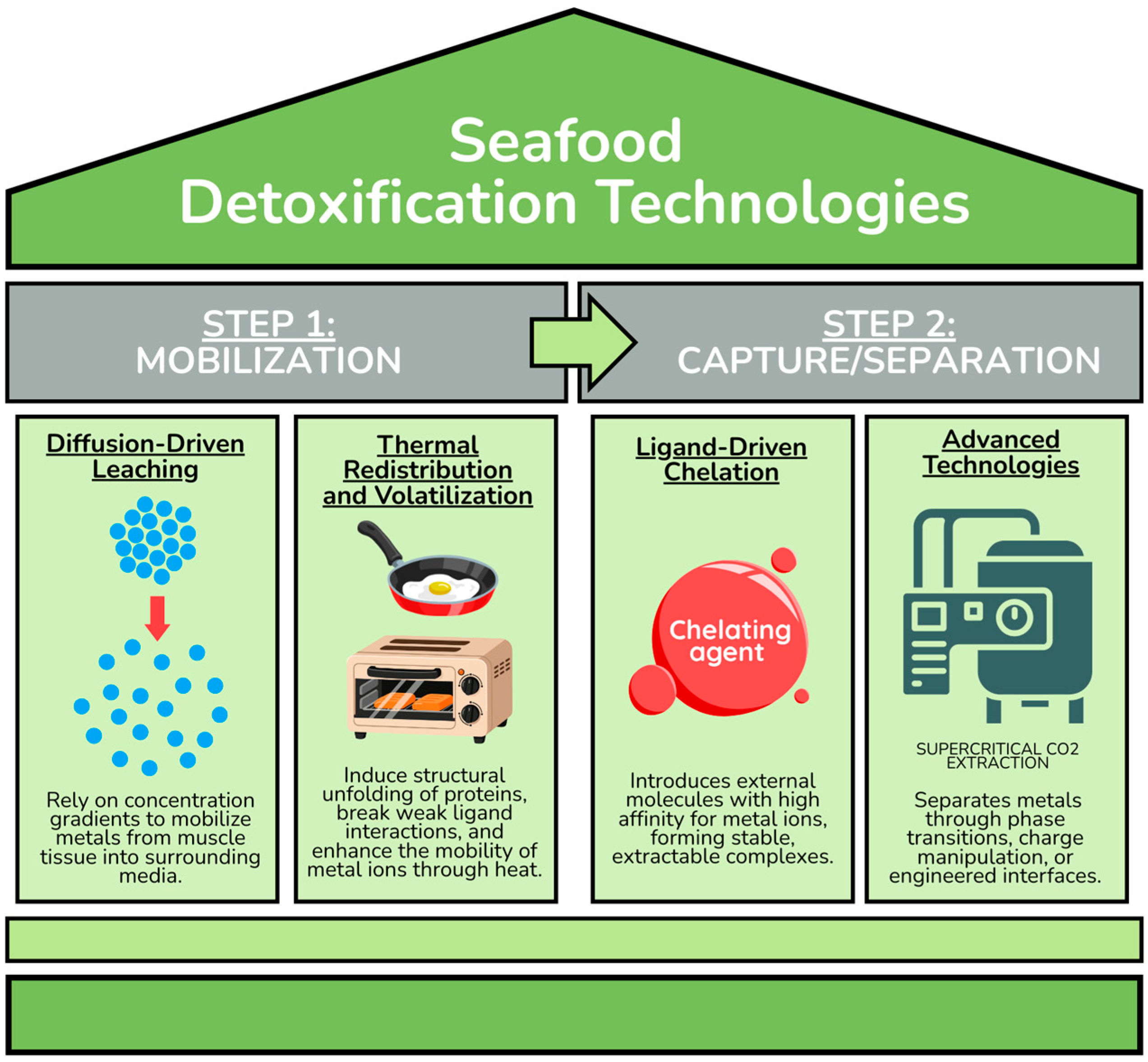

Although these post-mortem treatments have been individually reported, the field remains fragmented, with limited mechanism-guided guidance on how to select, compare, and combine interventions across metals and seafood matrices. The present work contributes a mechanistic framework that organizes

post-mortem detoxification into four physicochemical pillars (

Figure 1) and translates these mechanisms into a practical process-selection logic. On this basis, we propose feasible hybrid processing pathways that combine rapid mobilization steps (e.g., diffusion-driven leaching) with high-affinity capture or separation steps (e.g., chelation or electrocoagulation) to improve applicability in real processing scenarios.

2. Detoxification Methods Interpreted Through a Mechanism Guided Two-Step Framework

Detoxification methods used to reduce heavy metals in seafood operate through distinct physicochemical pathways that mobilize, transform, or remove metal ions from

post-mortem tissues. These approaches can be grouped into four mechanistic categories: diffusion-driven leaching, where acidic or saline media promote outward migration of metals; thermal redistribution or volatilization, in which heat disrupts protein-metal interactions and enhances ion mobility; chelation-based strategies that introduce ligands with high affinity for specific metals; and advanced physicochemical technologies that separate contaminants through engineered interfaces, phase transitions, or charge-based aggregation (

Figure 1). Together, these mechanisms form the foundation of current and emerging interventions aimed at improving seafood safety.

When considered collectively,

post-mortem heavy-metal reduction methods can be interpreted within a two-step conceptual framework based on their dominant mechanistic role (

Figure 1). Rather than viewing individual techniques as isolated solutions, this framework distinguishes between approaches that primarily promote metal mobilization and those that enable metal capture or separation.

Mobilization refers to processes that weaken metal–tissue interactions or shift metal species toward more labile states, thereby increasing their accessibility. Diffusion-driven leaching and thermal treatments fall within this category, as they modify concentration gradients, protein structure, or binding equilibria. In contrast, capture and separation mechanisms act on mobilized metals through selective complexation, aggregation, or physicochemical partitioning, as observed for chelation-based strategies and advanced separation technologies.

This framework is intended as an interpretative tool, not a processing prescription. It provides a basis for understanding differences in reported efficiencies across studies and for identifying mechanistic complementarities between approaches. By separating mechanistic function from specific technological implementation, the framework supports structured comparison of heterogeneous results and clarifies how different detoxification strategies may theoretically interact under practical and regulatory constraints.

2.1. Diffusion-Driven Leaching (Marination, Acid Soaking)

Within the two-step framework proposed, diffusion-driven leaching functions primarily as a metal mobilization mechanism, increasing the availability of loosely bound metal species for subsequent capture or separation. Diffusion-driven leaching methods rely on concentration and pH gradients to promote the outward migration of metal ions from seafood tissues into surrounding acidic or saline media, making marination and soaking among the simplest studied

post-mortem detoxification strategies. A summary of the effectiveness of diffusion-driven leaching methods can be found on

Table 1. A lot of these diffusion-driven leaching methods are in reality pre-cooking treatments such as soaking in saline or acidic solutions. For instance, acidic marination in a vinegar-based brine led to a tenfold decrease in As in Rainbow Trout fillets [

5]. The authors suggested that this decrease in As was due to the As compounds diffusing out into the marinade solution. In Tilapia fillets, something similar is reported by Basak et al. [

6], who used a saline soak at a moderate temperature (75 °C), successfully lowering the Ni and Cu content. This illustrates how acidic or ligand-containing soaking media can sequester metal ions and diminish their biological availability. Nonetheless, applying strongly acidic treatments in domestic culinary settings remains constrained, as they may alter sensory attributes, particularly flavor and texture.

2.2. Thermal Redistribution or Volatilization (Boiling, Frying)

From a mechanistic perspective, thermal treatments are likewise positioned within the mobilization stage of the two-step framework, as their primary effect is the disruption of metal–protein interactions rather than selective metal removal. Thermal treatments such as boiling and frying facilitate heavy metal reduction by altering protein structures, disrupting metal–ligand interactions, and in some cases promoting the volatilization or redistribution of metal species within the tissue matrix. Most of these methods are, at their core, culinary techniques that can also deeply influence the levels of toxic metals in fish tissue. Experiments have found that cooking methods are able to reduce heavy metal concentrations in Tilapia, specifically, Cd, Pb, Cu and Zn, with the biggest reduction being achieved by dry-baking [

7]. This reduction was attributed to the metals being released through the drip loss and the steam condensate while baking at high temperatures with convection. Reductions were also found while boiling and steaming, being attributed to the heavy metals migrating from the fish tissue into the cooking liquid [

7]. A more recent study in Carp found similar reductions, with a ~54% reduction on Cu after 5 min of boiling, and an even greater reduction when frying [

8]. Although thermal processing can promote metal migration out of fish tissue, the collective evidence indicates that boiling may be comparatively less effective than lipid-based or dry-heat methods. Studies show that baking and frying consistently achieve higher percentage reductions, suggesting that certain metals exhibit greater solubility or mobility in oil or rendered lipids than in water. This aligns with observations that volatilization, fat drip loss, and oil-mediated partitioning collectively enhance metal removal more efficiently than simple leaching into boiling water [

8].

Table 1.

Summary of the post-mortem removal technique types of Diffusion-driven leaching (marination, acid soaking) and Thermal distribution or volatization (boiling/frying).

Table 1.

Summary of the post-mortem removal technique types of Diffusion-driven leaching (marination, acid soaking) and Thermal distribution or volatization (boiling/frying).

| Method (Treatment) | Species/Product | Heavy Metal | Reduction Achieved | Ref. |

|---|

| Diffusion-driven leaching (marination, acid soaking) |

| Acidic marination (vinegar) | Rainbow trout fillets (pickled) | Arsenic (As) | ~90% reduction (10× decrease in As) | [5] |

| Salt-water soaking (10% NaCl, 75 °C (348.15 K)) | Tilapia fillets (pre-drying) | Nickel (Ni), Copper (Cu) | Significant reduction (>30% lower levels) | [6] |

| Thermal redistribution or volatilization (boiling, frying) |

| Boiling (5 min) | Common carp fillets | Copper (Cu) | 54.1% reduction | [8] |

| Frying (pan-fry) | Common carp fillets | Copper (Cu) | 80.3% reduction | [8] |

| Microwaving | European sea bass fillets | Lead (Pb) | 44% reduction | [9] |

2.3. Chelation and Ligand-Specific Removal

In contrast to mobilization-oriented interventions, chelation-based approaches primarily operate at the capture stage of the two-step detoxification framework. Chelation-based approaches achieve detoxification by introducing ligands with strong and selective affinity for metal ions, enabling the formation of stable, extractable complexes that can be leached from seafood tissues with high efficiency. Food-grade chelation agents, such as sodium citrate and sodium oxalate, can be introduced in a soaking solution, at a specified temperature, during a specified amount of time. Several studies demonstrate the effectiveness of these soaks (

Table 2). For example, soaking

Perna viridis in a solution of trisodium citrate (0.600 kg/m

3, 1 h, ~30 °C) successfully removed 21–38% of Pb, Cd, and Ni from the mussel tissue [

10,

11]. Research on marine algae further illustrates EDTA’s strong chelating capacity. A moderate EDTA treatment (0.1 M at 50 °C) increased cadmium release from kelp by approximately sevenfold relative to water alone [

12]. When applied in combination with ultrasounds, EDTA achieved even greater efficiencies, removing more than 50% of Cd and 32% of As from brown seaweed within only 5 min [

12]. These ligands primarily promote metal removal by leaching ions from muscle proteins and tissue matrices, with their efficiency dictated by the specific metal-ligand binding strengths (for example, acetate generally forms more stable complexes with Pb and Ni than citrate). EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) represents an even more potent chelating agent, capable of binding a wide spectrum of heavy metals. Their effectiveness therefore depends not only on ligand affinity, but also on the prior accessibility of metal species within the tissue matrix.

2.4. Physicochemical Separation via Advanced Technologies

Within the two-step framework, advanced physicochemical technologies are primarily associated with metal capture and separation, although some (e.g., ultrasound-assisted treatments) may also enhance mobilization by accelerating mass transfer. Advanced physicochemical technologies remove heavy metals through engineered separation mechanisms, such as phase partitioning, charge-induced aggregation, pressure-driven extraction, or surface-mediated adsorption, offering high-efficiency detoxification approaches beyond traditional processing methods. Some examples include supercritical fluid extraction, electrochemical removal and ultrasound-assisted detoxification. Some of the results of these techniques can be found on

Table 2. In fish oil, using supercritical fluid extraction with optimal parameters, achieved 93–98% reductions in Pb, Cd, As, and Hg levels [

13]. Importantly, the resulting oil maintained its quality and fatty-acid composition, suggesting that metals were successfully separated without compromising nutritional integrity. Because supercritical CO

2 selectively solubilizes lipids, the heavy metals likely remained in the residual solid matrix or were retained within the extraction vessel. This technique is regarded as a “green” alternative, as it eliminates the need for organic solvents and operates within a closed, environmentally benign system.

Electrochemical methods remove heavy metals by using an electric current to mobilize ions out of fish tissue and into surrounding water, where they are captured by coagulated flocs. In contaminated tilapia, treatment in distilled water with aluminum electrodes at ~6.2 V for about 35 min achieved roughly 90% removal of total heavy metals [

14]. Response-surface optimization indicated that moderate voltage and sufficient immersion time maximized removal while preserving tissue integrity [

14]. In seafood and seaweed processing, sonication through ultrasounds accelerates the diffusion of metal ions out of the matrix and can also increase the penetration of chelating agents [

12]. In edible seaweed, as referred in the previous section, ultrasound at 50 °C roughly doubled As release compared with static soaking [

12]. When combined with 0.1 N EDTA, however, ultrasound markedly increased efficiency, achieving 52% Cd removal, 32% As removal, and 31% iodine reduction within 5 min [

12], although ultrasound by itself did not significantly affect Cd or iodine removal.

These advanced technologies consistently outperform traditional methods by removing heavy metals more efficiently and in shorter treatment times. Importantly, they also preserve product quality, showing that high levels of detoxification can be achieved without compromising nutritional value. Together, these findings highlight their strong potential for practical, scalable use in seafood processing.

3. Effectiveness Across Techniques and Limitations of Current Evidence

While each detoxification approach operates through distinct mechanisms, a cross-technique comparison informed by the proposed two-step framework highlights important trade-offs for practical application. Traditional methods such as boiling, marination, and saline soaking are simple, low-cost, and already embedded in existing processing workflows, but within the two-step framework they function primarily as mobilization mechanisms, which partly explains their generally modest standalone removal efficiencies [

5,

6,

8,

9]. Chelation-based treatments, which operate at the capture stage of the two-step framework, can achieve far greater reductions, often exceeding 70–90% for specific metals, but require controlled conditions [

15,

16,

17]. They also generate waste solutions (chelate solutions contaminated with heavy metals) and face regulatory limits. From a theoretical standpoint, the framework suggests that combining an initial mobilization step (e.g., mild acid soaking or thermal treatment) with a subsequent capture-oriented intervention (e.g., ligand-based chelation) could enhance overall efficiency by increasing metal accessibility prior to selective binding, even when neither approach achieves high removal independently. Ultrasound-assisted treatments and electrocoagulation, which are predominantly also associated with the capture and separation stage of the framework (while potentially enhancing mobilization through mass-transfer effects), offer rapid and highly efficient removal but remain at early technological readiness levels and demand specialized equipment or energy inputs [

12]. Supercritical CO

2 extraction delivers the highest reported efficiencies, particularly for oils, but its applicability to whole fillets is limited and the required infrastructure is costly [

13]. These contrasts illustrate that no single technique is universally optimal and that, within the two-step framework, feasibility depends on how effectively mobilization and capture functions are matched to product type, processing environment, and regulatory context. Interpreting reported efficiencies through the two-step framework helps explain why similar technologies yield divergent results across studies, as mobilization-limited systems cannot achieve high removal even when capture mechanisms are highly efficient.

It is also important to acknowledge limitations within the current body of evidence. Reported efficiencies vary widely across species, tissue types, and product matrices, with many studies conducted on small sample sizes or under laboratory conditions that do not fully reflect industrial realities. Methods validated in muscle tissue may not translate directly to fatty matrices, and the results obtained in seaweed or oils cannot be assumed to apply to whole fish or seafood items. In addition, several studies rely on controlled soaking volumes, tailored pH adjustments, or fixed temperatures that may be difficult to replicate at scale. These factors introduce uncertainty when extrapolating laboratory findings to commercial processing settings. Recognizing these constraints helps clarify where further validation, pilot testing, and real-world trials are needed before large-scale implementation can be recommended.

A further limitation of the current evidence is the limited consideration of toxicological relevance. From a two-step framework perspective, high percentage removal does not necessarily imply risk mitigation if mobilization and capture do not reduce final concentrations below regulatory thresholds. Many studies still report percentage reductions without evaluating whether the final concentrations fall below regulatory thresholds such as the EU maximum levels for Hg, Cd, and Pb in fishery products [

18]. As a result, it is often unclear whether the observed decreases translate into meaningful reductions in consumer risk. Incorporating post-treatment concentrations relative to established limits would strengthen the applied relevance of these findings and clarify which methods achieve not only high removal efficiency but also compliance with food-safety standards.

4. Conclusions

This short review shows that post-mortem processing can substantially reduce heavy metal levels in seafood, with both traditional and advanced methods demonstrating clear efficacy. Acidified marinades have achieved reductions of up to tenfold for arsenic in rainbow trout, and thermal treatments such as frying can remove more than 80% of copper from carp. Chelation strategies using food-grade ligands remove up to 88% of lead, 80% of nickel, and over 90% of mercury in mussels, while ultrasound-assisted EDTA treatments reach 52% cadmium and 32% arsenic reduction within minutes. Among the most efficient technologies, supercritical CO2 extraction achieves 93–98% removal of toxic elements in fish oil, and electrocoagulation eliminates roughly 90% of total heavy metals in tilapia. Although these results highlight strong potential for improving seafood safety, industrial adoption will require overcoming constraints related to space, treatment time, regulatory acceptance, and preservation of product quality. Moreover, when viewed through the proposed two-step framework, post-mortem detoxification emerges not as a question of identifying a single optimal technology, but of matching mechanistic function to matrix constraints and processing context. Continued work focused on scalable process design and real-world validation will be essential for bringing these promising detoxification strategies into routine practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.P. and A.O.S.J.; methodology, M.B.P.P.O.; validation, M.C., J.E. and P.B.; formal analysis, J.E.; investigation, P.B.; resources, M.C.; data curation, A.O.S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.S.J.; writing—review and editing, M.B.P.P.O.; visualization, R.N.-M.; supervision, M.B.P.P.O.; project administration, M.B.P.P.O.; funding acquisition, M.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received financial support from the PT national funds (FCT/MECI, Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and Ministério da Educação, Ciência e Inovação) through the project UID/50006—Laboratório Associado para a Química Verde—Tecnologias e Processos Limpos. The authors are also grateful to the same institution for the individual research grants of J. Echave (2023.04987.BD) with the DOI

https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.04987.BD and A.O.S. Jorge (2023.00981.BD), with the DOI identifier

https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.00981.BD. The author also acknowledges the support given by Xunta de Galicia for the pre-doctoral grant of P. Barciela (ED481A-2024-230).The authors thank the EU-FORA Fellowship Program (EUBA-EFSA-2024-ENREL-01) for supporting the the work of A.O.S. Jorge within the framework of the project Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Fish from a Major European Fishing Hub—RAHMFISH.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created in the elaboration of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stanciu, M. Evolution of food consumption patterns at global level over the last five decades. J. Community Posit. Pract. 2020, 2020, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhan, P.; Lansubsakul, N.; Phaochoosak, N.; Sirinupong, P.; Yeesin, P.; Imsilp, K. Human Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal Concentration in Seafood Collected from Pattani Bay, Thailand. Toxics 2022, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuzzhassarova, G.; Azarbayjani, F.; Zamaratskaia, G. Fish and Seafood Safety: Human Exposure to Toxic Metals from the Aquatic Environment and Fish in Central Asia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajeb, P.; Jinap, S. Reduction of mercury from mackerel fillet using combined solution of cysteine, EDTA, and sodium chloride. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 6069–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieślik, I.; Cieslik, E.; Topolska, K.; Szczurowska, K.; Migdał, W.; Gambus, F. Changes in the content of heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Hg, As, Ni, Cr) in freshwater fish after processing—The consumer’s exposure. J. Elem. 1970, 23, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, P.; Ali, M.; Isra, L.; Rahman, M.; Haq, M. Effects of Thermal and Salt Water Soaking Pretreatment on the Physicochemical and Nutritional Properties of Sundried Tilapia Fish (Oreocromis niloticus) Products. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atta, M.B.; El-Sebaie, L.A.; Noaman, M.A.; Kassab, H.E. The effect of cooking on the content of heavy metals in fish (Tilapia nilotica). Food Chem. 1997, 58, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidoni, D.G.; Gheorghe, S.; Negrea, S.C.; Pacala, A.; Pahomi, A. The transfer of heavy metals from the water “in the dish”, through fish. Rom. J. Ecol. Environ. Chem. 2024, 6, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, B.; Yanar, Y.; Küçükgülmez, A.; Çelik, M. Effects of four cooking methods on the heavy metal concentrations of sea bass fillets (Dicentrarchus labrax Linne, 1785). Food Chem. 2006, 99, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azelee, I.W.; Ismail, R.; Bakar, W.A.W.A.; Ali, R.; Mohamed, R.; Samsudin, N.A.; Baharin, H. Catalyzed Trisodium Citrate as a Medium for Heavy Metals Treatment in Green-Lipped Mussels (Perna viridis). Mod. Res. Catal. 2013, 2, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Abdullah, W.N.; Naushad Ali, S.N.; Shukri, N.M.; Wan Mokhtar, W.N.A.; Yahaya, N.; Mat Rosid, S.J. Chelation technique for the removal of heavy metals (As, Pb, Cd and Ni) from green mussel, Perna viridis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 372–376. [Google Scholar]

- Noriega-Fernandez, E.; Sone, I.; Astrain-Redin, L.; Prabhu, L.; Sivertsvik, M.; Alvarez, I.; Cebrian, G. Innovative Ultrasound-Assisted Approaches towards Reduction of Heavy Metals and Iodine in Macroalgal Biomass. Foods 2021, 10, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajeb, P.; Jinap, S.; Shakibazadeh, S.; Afsah-Hejri, L.; Mohebbi, G.H.; Zaidul, I.S. Optimisation of the supercritical extraction of toxic elements in fish oil. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2014, 31, 1712–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandra, S.; Hendrawan, Y.; Perdana, T.W.; Lutfi, M.; Argo, B.D. Modeling and Optimization of Electrocoagulation Voltage and Water Immersion Time on Heavy Metal Reduction in Fish. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2020, 10, 2088–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Abdullah, W.N.; Naushad Ali, S.N.; Shukri, N.M.; Wan Mokhtar, W.N.A.; Yahaya, N.; Mat Rosid, S.J. Catalytic chelation technique for the removal of heavy metal from Clarius batrachus (C. batrachus). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.; Mohd Yusoff, A.R.; Bakar, W.; Ismail, R.; Hadiyanto, D.P. Removal of selected heavy metals from green mussel via catalytic oxidation. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2014, 18, 271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Wan Azelee, I.; Ismail, R.; Ali, R.; Bakar, W. Chelation technique for the removal of heavy metals (As, Pb, Cd and Ni) from green mussel, Perna viridis. Indian J. Mar. Sci. 2014, 43, 372–376. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. Comission regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 364, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |