Abstract

Research on human–animal relationships suggests that close bonds with animals can enhance empathy, reduce speciesism, and improve human physical and psychological health. This study investigated whether pet ownership—particularly attachment to a companion animal during childhood—is associated with differences in moral concerns toward all animals in adulthood. It also aimed to explore the potential effects of empathy and speciesism on overall moral concerns toward animals. Using self-report questionnaires among 72 participants recruited online, the analyses revealed a significant effect of animal categories on moral concerns, F(1, 1.98) = 59.37, p < 0.001. Mean moral concern scores were significantly higher for companion animals (M = 6.04, SD = 1.15) than for food animals (M = 4.90, SD = 1.44), unappealing wild animals (M = 4.20, SD = 1.87), and appealing wild animals (M = 5.73, SD = 1.32), p < 0.05. Additionally, childhood pet owners reported greater moral concerns for all animals, F(1, 1.98) = 4.87, η2 = 0.065, p < 0.05. Attachment to a companion animal in childhood was positively correlated with moral concerns for all animal categories. Finally, although attachment and empathy were both positively related to moral concern, only attachment was a significant predictor (p < 0.05). Further research is needed to understand the psychological mechanisms influencing views on animal rights and welfare.

1. Introduction

Human–animal interactions have existed for millions of years and have played an essential role in the sustainability of our ecosystem [1]. While animals have been considered in regard to their utilitarian function for years (e.g., meat), their roles as companions and even family members have become increasingly prominent over recent decades—especially in Western societies [2]. Nevertheless, humans do not perceive all animals the same way; companion animals (e.g., dogs) are still more valued than farm animals (e.g., cows) [2]. This difference of treatment is called speciesism—in other words, the “prejudice or attitude of bias in favour of the interests of members of one’s own species and against those of members of other species” [3] (p. 35). Research also suggested that familiarity and perceived attractiveness of different animals can influence humans’ moral concerns towards them [4].

Attachment theory can provide another framework for discussing human–animal bonds. Bowlby [5], who initially developed the concept, believed that attachment is an innate drive in children and causes them to seek psychological and physical proximity with their caregivers. Similar bonds may also exist between humans and animals [6]. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that companion animals can serve as attachment figures for children, offering them emotional comfort and facilitating their socioemotional development. However, research on children’s attachment to animals remains underexplored to this day, with most empirical studies focusing on adults [7].

Some evidence suggests that a prior relationship with a companion animal may increase levels of empathy and moral concerns towards animals in adulthood. For example, the “pets as ambassadors” hypothesis, developed by Paul and Serpell [8], posits that pet ownership in childhood leads to more positive attitudes towards all kinds of animals in adulthood. Another cross-cultural study among UK and Japanese populations also revealed that interactions with animals from an early age can influence adults’ perspectives on animal welfare [9].

Although there is conflicting evidence in the literature, some research suggests that children exhibit lower levels of speciesism than do adults, as they are less inclined to categorize animals (e.g., companion, farm, or wild animals) into distinct groups. Children begin to learn about moral concepts from an early stage of their development [10], and the act of categorization seems to play a role in determining the moral worth of animals. Therefore, by interacting with animals and learning about their welfare, children may be more likely to critically examine commonly held or culturally transmitted beliefs about them. In contrast, adults tend to attribute moral status based on species membership [11].

The present study aimed to address a neglected aspect in the literature: the influence of emotional attachment to a companion animal during childhood on the development of moral concerns towards animals in adulthood. By focusing on early human–animal interactions, this research sought to understand the long-term impact of attachment on ethical attitudes towards a wide range of animal species (companion, food, appealing and unappealing wild animals). Based on the existing research, three hypotheses were generated. Firstly, there will be differences in moral concerns for different species of animals. Secondly, there will be differences in moral concerns towards animals between participants delineated by pet ownership in childhood, i.e., pet owners vs. non-pet owners in childhood. Finally, the intensity of the bond with an animal companion during childhood will correlate with moral concerns towards animals in adulthood.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

The study was quantitative and employed online self-report questionnaires to investigate the relationship between attachment to a companion animal in childhood and the development of moral concerns towards all animals in adulthood. For convenience, data were collected through the JISC platform.

2.2. Participants

Participants over 18 years old were recruited through convenience and purposive sampling to ensure that the sample was representative of the two categories of participants (pet owners vs. non-pet owners in childhood). For convenience sampling, the research team sent the study link to acquaintances and university students via social media, and they were also encouraged to share it among their networks. In total, we recruited 87 participants, although 15 were excluded from further analysis due to incomplete answers or extreme scores. Extreme scores were identified through visual inspection of the box plots. If they appeared as outliers, showing values inconsistent with the rest of the distribution, they were considered for exclusion. The remaining 72 participants consisted of 13 men and 59 women, with an age range of 20 to 73 years old (M = 40.36, SD = 12.80). As for the dietary preferences, the majority of participants were omnivores (75%), followed by flexitarians (16.7%), vegetarians (4.2%), vegans (2.8%), and pescatarians (1.4%).

The study comprised two cohorts: pet owners in childhood (52 participants) and non-pet owners in childhood (20 participants). Even though the two cohorts show an unequal number of participants, data [12] indicates that 77% of British children have a pet, which is in line with the percentages of participants in the two current cohorts.

2.3. Materials and Procedure

At the beginning of the study, participants were required to read the information sheet and provide their informed consent. Subsequently, they were asked a series of demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, nationality), as well as some general questions about their history with companion animals (e.g., pets owned, relationship with animals).

Afterwards, all the participants were required to complete the Moral Concerns for Animals Measure [13]. It included four categories of animals: companion, wild appealing, food, and wild unappealing animals. The measure aimed to investigate the differential treatment and moral consideration of various animals. The participants were required to indicate to what extent they felt a moral obligation towards the different categories of animals (the names of the categories were not displayed to avoid influencing the answers). Answers were measured on a scale from 1 (no concern at all) to 7 (very much concerned), with higher scores indicating stronger moral concerns towards animals. Following the methods of Leite et al. [13], an average score for each category of animals has been calculated.

The participants who owned one or more companion animals during childhood were also asked to complete the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale [14]. This is a 23-item instrument presented in a 4-point Likert scale format, which allowed the researcher to measure the intensity of attachment between the owner and the companion animal. It possesses good internal consistency and construct validity [15]. The participants indicated whether they strongly disagreed (score = 0) or strongly agreed (score = 3) with the statements. Higher scores indicated a greater attachment to an animal. In this study, the researchers asked participants to complete the questionnaire retrospectively by thinking about the pet with which they had the strongest bond during childhood.

Additionally, all the participants answered the Speciesism Scale [16] and the Animal Empathy Scale [17]. The Speciesism Scale, created by Caviola et al. [16], consisted of six questions in which participants were asked to decide whether they strongly disagreed (score = 0) or strongly agreed (score = 7) with each statement. Higher scores indicated more speciesist beliefs. Since participants can be raised with pets but still hold a speciesist belief system, this measure allowed the researcher to moderate relationships between different variables. The Animal Empathy Scale [17] was used to determine whether empathy could be a factor explaining the differences in moral concerns for animals between the participants. The scale consisted of 22 items, and participants were required to decide to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the statements. Responses to each statement were scored using a 9-point Likert-type scale (range = 0 to 176), with 11 empathic items and 11 non-empathic items. Higher scores indicated greater empathy towards animals.

At the end of the survey, the participants received a debrief form and were thanked for their involvement in the study. The survey lasted no longer than 15 min.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS for Mac version 29. For all tests, p < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

2.4.1. Moral Concerns Across Animal Categories for All Participants

The first hypothesis employed a within-subjects design, using the Moral Concerns for Animals Measure to assess differences in moral concerns across animal categories. The hypothesis was tested using a repeated measures ANOVA to examine the differences in moral concerns for the four categories of animals (food, companion, appealing wild, and unappealing wild animals). When inspecting box plots and Q–Q plots, it was concluded that the data were normally distributed. A Mauchly’s Test for Sphericity was not assumed (p < 0.001), so the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used (ε = 0.661), as it is recommended to use this correction when epsilon is lower than 0.75 [18]. No extreme outliers were found. As ANOVA is robust against violations of the normality assumption [19], we decided to retain minor statistical outliers for the analysis.

2.4.2. Moral Concerns Towards Animals Between Participants

The second hypothesis used a between-subjects quasi-experimental design, and the effect of pet ownership on moral concerns scores was analyzed using a 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA, with two different pet groups (pet owners vs. non-pet owners in childhood) as the between-participant factor, and moral concerns for different categories of animals (food, companion, appealing wild, and unappealing wild animals) as the within-participant factor. Inspection of the data (using box plots and Q–Q plots) revealed a normal distribution. Because sphericity was not assumed, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used. Post hoc tests were not needed, as there were only two levels of the between-participant factor.

2.4.3. Childhood Attachment to an Animal and Moral Concerns

The last hypothesis employed a within-subjects correlational design, using the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale to assess the relationship between childhood attachment to a companion animal and moral concerns towards animals in adulthood. The hypothesis was tested using a Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficient to measure the strength and direction of the relationship between attachment and moral concerns towards animals. Inspection of the scatterplots suggested a linear relationship between attachment scores and moral concern scores for the four categories of animals (food, companion, appealing wild, and unappealing wild animal conditions). No extreme outliers were found.

2.4.4. Additional Measures for All Participants

The researchers also conducted additional analyses, such as independent sample t-tests, to examine the differences in speciesism and animal empathy between participants (using the Speciesism Scale and the Animal Empathy Scale, respectively). Histograms and box plots indicated normally distributed data with no outliers, allowing for the use of a parametric test. Levene’s test for equality of variances was assumed, with p >0.05. Moreover, a multiple regression analysis was used to further explore the interactions between speciesism, animal empathy, and attachment on moral concerns towards animals. After inspecting a matrix scatterplot, histograms, and box plots, the data were found to be normally distributed. Furthermore, the predictor variables did not correlate strongly with each other, so there was no multicollinearity. There were no outliers, so the variables were suitable for multiple regression.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

The two cohorts were equally matched in terms of age and gender. In the pet owners’ group, 52 participants (43 women, 9 men), aged 20 to 70 years old, owned one or more animals during their childhood (M = 39.92, SD = 12.10). In the non-pet-owning group, 20 participants (16 women, 4 men), aged 22 to 73 years old, did not own a pet during their childhood (M = 41.50, SD = 14.75). Mean scores of speciesism, empathy and moral concerns are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean scores of speciesism, empathy, and moral concerns towards animals by pet ownership status.

3.2. Moral Concerns Across Animal Categories for All Participants

The differences in moral concerns for different animal species were assessed using a repeated measures ANOVA. There are concerns about applying this method to ordinal Likert data. However, using normally distributed composite scores, it is generally thought that ANOVA is sufficiently robust to be used [20].

The mean score of moral concerns for the companion animal condition was the highest (M = 6.04, SD = 1.15), followed by the appealing wild animal condition (M = 5.73, SD = 1.32), the food animal condition (M = 4.90, SD = 1.44), and the unappealing wild animal condition (M = 4.20, SD = 1.87). Furthermore, there was a significant effect of animal categories on moral concerns, F(1, 1.98) = 59.37, p < 0.001, N = 72. The overall effect size was large (partial η2 = 0.45).

Bonferroni post hoc tests indicated that the mean score for moral concerns in the animal companion condition was significantly higher than in the food and unappealing wild animal conditions, with p < 0.001. It was also significantly higher than the appealing wild animal condition, with p < 0.05. Moreover, the mean score of moral concerns for the food animal condition was significantly lower than for the companion and appealing wild animal conditions, with p < 0.001. It was also significantly higher than the unappealing wild animal condition, with p < 0.001.

These results suggest that animal categories affect moral concerns, supporting the first hypothesis that there is a difference in moral concerns towards different species of animals. Specifically, people tend to display the highest level of moral concerns towards companion animals rather than towards other types (food, appealing wild, and unappealing wild). The findings also revealed that individuals seem to have the lowest levels of moral concerns towards unappealing wild animals.

3.3. Moral Concerns Towards Animals Between Participants

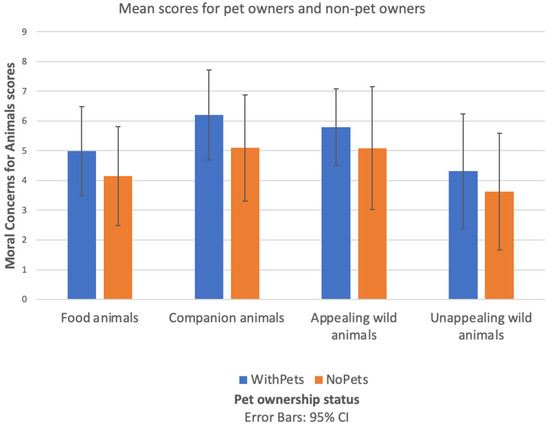

Moral concerns scores for animal categories according to pet ownership status during childhood are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. The effect of pet ownership on moral concern scores was analyzed using a 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA.

Table 2.

Moral concerns scores for animal categories according to pet ownership status during childhood.

Figure 1.

Graph showing moral concerns scores for different categories of animals between participants (pet owners vs. non-pet owners in childhood).

This analysis revealed that there was a significant main effect of pet ownership upon moral concerns, with F(1, 1.98) = 4.87, partial η2 = 0.065 (medium effect size), p < 0.05. Furthermore, as stated in hypothesis 1, there was a significant main effect of animal categories on moral concerns, with F(1, 1.98) = 43.65, partial η2 = 0.38 (large effect size). No significant interaction was found between the categories of animals and pet ownership status during childhood, with F(1, 1.98) = 0.65, partial η2 = 0.009, p > 0.05, suggesting no interaction between the different categories of animals and childhood pet ownership status. Therefore, the second hypothesis, stating that there will be a difference in moral concerns towards animals between childhood pet owners and non-pet owners, is supported.

3.4. Childhood Attachment to an Animal and Adult Moral Concerns

A Pearson’s correlation indicated a moderate positive and significant relationship between attachment and moral concerns scores (as shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

Pearson coefficient between attachment scores * and moral concerns for the four categories of animals.

The general mean of the 52 attachment scores was M = 46.56, SD = 16.26. There was a moderate, positive, and significant relationship between attachment scores and moral concerns for food animals (r = 0.35, p < 0.05, N = 52), companion animals (r = 0.45, p < 0.001, N = 52), appealing wild animals (r = 0.47, p < 0.001, N = 52), and unappealing wild animals (r = 0.39, p < 0.05, N = 52). Thus, the third hypothesis was confirmed by the results, indicating that moral concerns for different categories of animals increased as the intensity of the bond (attachment) with an animal companion increased.

3.5. Additional Measures for All Participants

To further explore the effect of attachment on moral concerns towards animals, speciesism and empathy have been used as additional variables to see if they can predict, along with attachment, different levels of moral concerns.

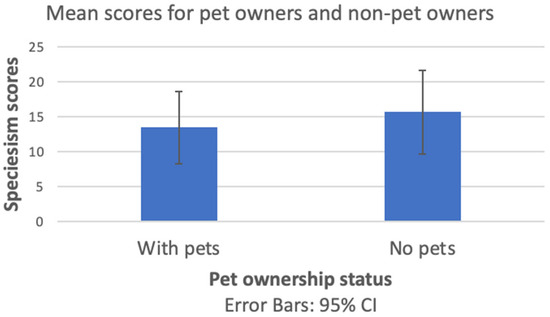

As shown in Figure 2, the mean scores of speciesism did not differ significantly between the two groups: pet owners (M = 13.46, SD = 5.15) and non-pet owners (M = 15.70, SD = 5.98). An independent sample t-test did not indicate any significant difference in these findings, t(70) = −1.58, p > 0.05, with a small to moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.42).

Figure 2.

Mean scores of speciesism between the participants (pet owners vs. non-pet owners).

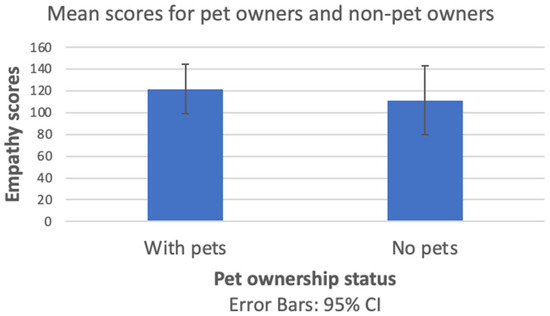

As shown in Figure 3, the mean score of animal empathy for the pet owner group (M = 121.65, SD = 22.83) was higher than the mean score for the non-pet owner group (M = 111.25, SD = 31.49). However, an independent sample t-test did not indicate any significant difference in these findings, t(70) = 1.55, p > 0.05, with a small to moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.41).

Figure 3.

Mean scores of animal empathy between the participants (pet owners vs. non-pet owners).

Finally, speciesism and empathy were analyzed among pet-owner participants as potential predictors of moral concerns.

Pearson’s coefficient revealed that empathy (r = 0.36) correlated positively with moral concerns, with p < 0.05, and that attachment (r = 0.45) also correlated positively with moral concerns, with p < 0.001. Furthermore, speciesism (r = −0.47) correlated negatively with moral concerns, with p < 0.001.

The multiple regression analysis indicated that the association between the criterion (moral concerns for animals) and the explanatory variables (attachment, speciesism, and empathy) was substantial (Multiple R = 0.60). Collectively, attachment, speciesism, and empathy accounted for 32% of the variance in levels of moral concerns towards animals (adjusted R-squared). The unstandardized regression coefficient for attachment was 0.59, t = 3.10, and was significant, with p < 0.05. The unstandardized regression coefficient for speciesism was −2.03, with a t-value of −3.18, and was significant at p < 0.05. However, the unstandardized regression coefficient for empathy was −0.10, t = −0.60, and was not significant, with p > 0.05.

4. Discussion

The study’s findings revealed that participants expressed different levels of moral concerns depending on the categories of animals. More specifically, they presented greater moral concerns towards companion and appealing wild animals compared to their concerns towards food and unappealing wild animals. The literature found similar results, suggesting that the way people morally care for animals is linked to how society treats and values particular species [21]. Currently, it is not uncommon for pet owners to consider their pets as family members [22]. This disparity in the treatment of different species could be explained by a tendency for people to more often attribute human traits to companion than to other types of animals. The greater dissimilarity of animal traits compared to those of humans, (e.g., those of snakes), the fewer cognitive abilities people attribute to these animals [23]. Consequently, people tend to develop lower levels of moral concerns towards these species [2].

Research also suggested that cuteness and attractiveness can affect moral concerns towards animals [24]. Some studies have suggested that appealing animals are perceived as more intelligent than unappealing ones, regardless of their actual cognitive capacities [25]. Similarly, baby-like traits among animals could trigger parental instincts in human beings, explaining why cute animals are often granted higher moral values [23].

The present study also found that speciesism levels correlated negatively with moral concerns towards animals. Several papers have suggested that animal categorization plays a significant role in explaining the differences in moral concerns for companion and food animals [11]. Depending on whether an animal is perceived as food or not, people appear to change their opinion about the intelligence and sentience of an animal, which plays a crucial role in determining the animal’s moral worth.

Additionally, we have identified different moral concerns towards animals among pet owners and non-pet owners during childhood. These results could be partially explained by intergroup contact theory. When applied to human relationships, intergroup contact can decrease intergroup prejudices [26]. Theoretically, this effect could be applied to the human–animal relationship, where contact with an animal species could reduce negative prejudices or attitudes towards that specific animal species. In this way, Auger and Amiot [27] suggested that contact with pets would have a similar effect to contact with friends, and that this form of cross-group bond could reduce intergroup prejudices and foster more positive attitudes towards animals. When applied to the “pets as ambassadors” hypothesis, they suggested that contact with pets could improve attitudes towards all animals by creating a more inclusive group encompassing both human and non-human animals. This would explain why individuals with one or more pets in childhood tend to exhibit greater moral concerns towards all animals than do those without pets.

Although it remains an under-researched topic, some studies suggest that the process of attributing moral worth to animals based on their species membership does not emerge during childhood but instead appears later in adolescence [11]. Therefore, forming a strong relationship with an animal during childhood could enhance an interest in non-companion animals that persists later on.

It has also been suggested that daily interactions with an animal could enhance empathy towards all animals [17] and reduce levels of speciesism [8]. Nevertheless, the present study found no differences in empathy and speciesism levels between the two cohorts. As a previous work indicates gender differences in animal empathy [8], our findings could be explained by the gender distribution in our research (with a high prevalence of women in both cohorts). Empathy levels are relatively high in this study, so it would be interesting to replicate it with a more balanced sample. Caviola [28] revealed that speciesism is often associated with empathy and social dominance orientation. Since there were no differences in animal empathy between the two cohorts, this might also explain why the speciesism levels did not differ.

Finally, the current research found that while both empathy and attachment are positively correlated with moral concerns, only attachment to a companion animal during childhood positively predicts moral concerns towards animals in adulthood. The literature suggests that emotional bonds with a companion animal may extend to different species through animal identification [27]. Additionally, belief in animal mind (BAM) may be stronger among children who possess a strong bond with their pet [29], suggesting that it is not merely the act of owning a pet but rather the emotional attachment to the animal that can enhance positive attitudes towards non-human species.

Several study limitations must be addressed. To begin with, the current study employed unequal sample sizes in the two cohorts, which may have impacted the statistical power of the analyses. Although the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used when appropriate, the imbalance in the number of participants means that the data should be interpreted with caution.

It is also worth noting that most of the literature has typically used Western choices of cats or dogs when discussing the psychological concepts of pet ownership, attachment, and empathy towards animals. Muldoon et al. [30] found that people tend to display lower levels of attachment towards reptiles and amphibians. However, it would be interesting to explore whether owning a greater range of companion animals during childhood (e.g., turtles) might influence the generalizability of people’s moral concerns. On a related point, the Moral Concerns for Animals Measure used in our research included an unequal number of animals within the categories (e.g., three companion animals compared to eight farm animals) and an ethnocentric classification of those animal categories. With hindsight, this could have biased the data, making it difficult to apply the findings to different populations.

The present study also used retrospective self-report questionnaires to measure attachment to an animal. However, participants might falsely recall their relationship with a companion animal and be subject to distorted memory. Consequently, to avoid a retrospective design, future longitudinal research is needed among children and teenagers to assess their attachment to a companion animal and measure it over time. Moreover, the gender imbalance in our sample might have impacted the results of our research. Indeed, Herzog [31] found significant gender differences in human–animal interactions, with women showing more positive attitudes towards animals and higher levels of attachment towards them compared to the results for men. It would be useful to replicate our current study with a more balanced sample to determine whether the positive effect of attachment on the development of moral concerns towards animals remains.

Finally, this study revealed that attachment to an animal during childhood is a better predictor of moral concerns towards non-human species than of empathy towards animals. This finding has significant implications for educational programs, as education provides young people with the opportunity to develop their moral reasoning [32]. Yet, children can become powerful catalysts for change in environmental protection [33]. Therefore, encouraging children to engage in pet care behavior could promote prosocial attitudes and greater concerns towards animal welfare [34].

5. Conclusions

This study examined the relationship between childhood attachment to a companion animal and moral concern for animals in adulthood. While past research has focused on pet ownership and attitudes, few studies have examined the role of attachment in this context. Results indicate that stronger childhood attachment predicts greater moral concern for various types of animals later in life. This may be due to early interactions with non-human animals, which foster empathy and interest in animal welfare.

Participants showed greater concern for companion and appealing wild animals than for food or less attractive species—a difference partially linked to the “cute response”. Although childhood pet ownership alone did not affect speciesism or empathy levels, it did predict overall moral concern more strongly than empathy itself. These findings suggest that educational programs incorporating pet-related content may foster broader moral concerns for all animals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.-M. and D.S.S.; methodology, L.B.-M.; formal analysis, L.B.-M.; investigation, L.B.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.-M.; writing—review and editing, L.B.-M., D.S.S., N.M.-B. and N.B.-B.; supervision, D.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Robert Gordon University (protocol code LBM260523 and 26 May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author L.B.M. used an AI tool to convert the referencing style from APA to MDPI, as well as to reformulate the conclusion for academic purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marriott, S.; Cassaday, H.J. Attitudes to animal use of named species for different purposes: Effects of speciesism, individualising morality, likeability and demographic factors. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B.; Loughnan, S. Resolving the Meat-Paradox: A Motivational Account of Morally Troublesome Behavior and Its Maintenance. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 21, 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, P. Animal Liberation, 4th ed.; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dhont, K.; Hodson, G.; Loughnan, S.; Amiot, C.E. Rethinking human-animal relations: The critical role of social psychology. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2019, 22, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Haire, M. Companion animals and human health: Benefits, challenges, and the road ahead. J. Vet. Behaviour. 2010, 5, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsa-Sambola, F.; Muldoon, J.; Williams, J.; Lawrence, A.; Connor, M.; Currie, C. The Short Attachment to Pets Scale (SAPS) for Children and Young People: Development, Psychometric Qualities and Demographic and Health Associations. Child Indic. Res. 2016, 9, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S.; Serpell, J.A. Childhood Pet Keeping and Humane Attitudes in Young Adulthood. Anim. Welf. 1993, 2, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, A.; Bradshaw, J.W.S.; Tanida, H. Childhood Experiences and Attitudes Towards Animal Issues: A Comparison of Young Adults in Japan and the UK. Anim. Welf. 2023, 11, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Cowell, J.M. Interpersonal harm aversion as a necessary foundation for morality: A developmental neuroscience perspective. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, L.; Palmer, S.B.; Faber, N.S. The Development of Speciesism: Age-Related Differences in the Moral View of Animals. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2022, 14, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, T. UK pet ownership at 62% overall in 2022, dogs top list. Pet Food Industry. Available online: https://www.petfoodindustry.com/news-newsletters/pet-food-news/article/15468847/uk-pet-ownership-at-62-overall-in-2022-dogs-top-list (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Leite, A.C.; Dhont, K.; Hodson, G. Longitudinal effects of human supre.macy beliefs and vegetarianism threat on moral exclusion (vs. inclusion) of animals. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.P.; Garrity, T.F.; Stallones, L. Psychometric Evaluation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS). Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templer, D.I.; Arikawa, H. The Pet Attitude Scale. In The Psychology of the Human-Animal Bond; Blazina, C., Boyraz, G., Shen-Miller, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 335–359. [Google Scholar]

- Caviola, L.; Everett, J.A.C.; Faber, N.S. The moral standing of animals: Towards a psychology of speciesism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 116, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S. Empathy with animals and with humans: Are they linked? Anthrozoös 2000, 13, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girden, E.R. ANOVA Repeated Measures; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Blanca, M.J.; Arnau, J.; Garcia-Castro, F.J.; Alarcon, R.; Bono, R. Non-Normal Data in Repeated Measures ANOVA: Impact on Type I Error and Power. Psicothema 2023, 35, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, G. Likert Scales, Levels of Measurement and the “Laws” of Statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krings, V.C.; Dhont, K.; Salmen, A. The Moral Divide between High- and Low-Status Animals: The Role of Human Supremacy Beliefs. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, N.; Grauerholz, L. Interspecies Parenting: How Pet Parents Construct Their Roles. Humanity Soc. 2019, 43, 96–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A. Anthropomorphism and anthropomorphic selection--beyond the “cute response”. Soc. Anim. 2003, 11, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.J. “Bats, snakes and spiders, Oh my!” How aesthetic and negativistic attitudes, and other concepts predict support for species protection. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebl, C.; Luo, Y.; Poh-Jie Tan, N.; Ping Ern, J.T.; Bastian, B. Beauty of the Beast: Beauty as an important dimension in the moral standing of animals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 75, e101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 751–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, B.; Amiot, C.E. The impact of imagined contact in the realm of human-animal relations: Investigating a superordinate generalization effect involving both valued and devalued animals. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 85, e103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviola, L. How We Value Animals: The Psychology of Speciesism. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, R.; Williams, J. Childhood Attachment to Pets: Associations between Pet Attachment, Attitudes to Animals, Compassion, and Humane Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, J.C.; Williams, J.M.; Lawrence, A.B.; Currie, C. The Nature and Psychological Impact of Child/Adolescent Attachment to Dogs Compared with Other Companion Animals. Soc. Anim. 2019, 27, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H. Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It’s So Hard to Think Straight About Animals, 2nd ed.; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dolph, K.; Lycan, A. Moral Reasoning: A Necessary Standard of Learning in Today’s Classroom. J. Cross-Discip. Perspect. Educ. 2008, 1, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gottesdiener, H.; Davallon, J. Éducation pour l’environnement: L’enfant catalyseur du changement. Villes Parallèle 1999, 28–29, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.R.; Weber, C.V. Children’s Attitudes About the Humane Treatment of Animals and Empathy: One-Year Follow-Up of a School-Based Intervention. Anthrozoös 1996, 9, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).