Abstract

In this study, we focused on information regarding the food preparation process and aimed to investigate the influence of the presence of a person cooking on food evaluation. For the same-food-photo (rice ball or miso soup), participants had to complete a nine-item questionnaire related to their food evaluation using a seven-point Likert scale, divided into cases where only the name of the food was written and where it was written as being machine-made or handmade. We also administered the same questionnaire divided into cases with text-only recipes, with photos of cooking utensils and ingredients, or with photos of the cook. The groups labeled with only the food names and the handmade label had significantly higher scores than those labeled as being machine-made regarding healthiness, time and effort, and whether the food was ‘made with love.’ The text-only versions significantly improved the appearance of the miso soup compared to photos with the cook. This study revealed that information regarding food being handmade had a more positive impact than that which was machine-made, but this was comparable to text-only photos. Because the handmade label can be influenced by context, future research should investigate in more detail the circumstances in which the handmade label influences it.

1. Introduction

People’s preferences and perceptions of food change depending on the information they receive prior to eating. According to previous studies, sensory perceptions change when the food has an appealing name [1], and when food is given with good intentions it can improve its taste [2]. Furthermore, how food is prepared influences the consumers’ perception; several studies have shown that consumer involvement in food preparation can improve the consumer’s perception of the product [3,4].

Therefore, we believe that labeling a product as handmade can improve its appeal. Although technological advances have made it possible to mass-produce products in a uniform way, the value of handmade products resonates among young people [5]. In research contexts, handmade products have been compared to machine-made products, and the handmade products are generally perceived as more attractive and more likely to contain ‘love’ than machine-made products, increasing the chances they will be gifted to a loved one [6]. Furthermore, handmade gifts have been shown to promote social relationships [7]. A previous study on cooking showed that positive food quality prediction for dishes made by robotic chefs is lower than made by human chefs, and that increasing the anthropomorphism of the robot chef’s appearance can improve food quality predictions [8]. Based on this, advertising a dish as being made by a human is an effective way of improving a consumer’s impression of that dish.

Additionally, the perception of human contact during the manufacturing process influences how people evaluate food. A study that manipulated the typeface on product packaging revealed that handwritten typefaces (vs. machine-written typefaces) on food packaging create perceptions of human presence, thereby enhancing consumers’ emotional attachment to the product and leads to more favorable product evaluations [9]. Furthermore, experiments evaluating food have shown that if consumers believe human contact occurred during the production process, they perceive the product to be more natural [10] and that perceptions of naturalness increase impressions of authenticity and, therefore, the value of the food [11].

In this study, we conducted two experiments to investigate the effects of a handmade label alone and the presence of a human during the cooking process, with the aim of broadly investigating how human involvement in cooking affects consumer’s impressions of food.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study 1

Participants over 18 years of age were recruited through Lancers, a crowdsourcing service (42.2% female, total: 748, mean age (Mage) = 43.4 years, standard deviation (SD) = 10.4), with monetary compensation. The images of the food items were divided into groups where only the name of the food was written (control; 248 participants) and where it was described as machine-made (250 participants) or handmade (250 participants). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions in a between-subjects design and completed a nine-item questionnaire related to their evaluation of photos of food (rice ball and miso soup, Figure 1) using a seven-point Likert scale.

Figure 1.

Photos of the dishes used in Study 1 (left, rice balls; right, miso soup). Three labels (preparation process) were used: food name only (control), machine-made, or handmade.

2.2. Study 2

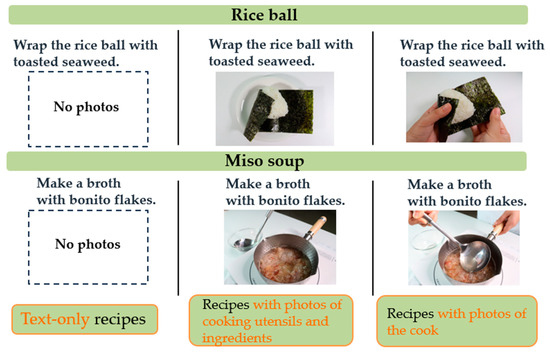

Participants were also recruited through Lancers (41.9% female, total: 1485, Mage = 43.7 years, SD = 10.2) with monetary compensation and were asked to view a recipe and then photos of the finished dish (rice balls, 735 participants; miso soup, 750 participants) and answer a questionnaire similar to that in Study 1. We also administered the same recipe, divided into groups with text-only recipes, with photos of cooking utensils and ingredients, and photos of someone cooking the food (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Examples of recipes and images presented in Study 2 questionnaire.

2.3. The Food Evaluation Questionnaire

The questionnaire was administered to the participants and scored using a 7-point Likert-type response scale ranging from 1–7 in Study 1 and Study 2. Appearance: “This dish looks good” (very bad/very good), healthiness: “This dish looks healthy” (very unhealthy/very healthy), expected goodness of taste: “This dish looks tasty” (It does not look very tasty/looks very tasty), intention to eat: “You would like to eat this dish” (I would not/would like to eat this dish), time and effort: “It takes time and effort to make this dish” (it does not take/takes the time and effort to make the dish), and expected saltiness “This dish looks salty” (very non-salty/very salty) were asked.

We also investigated mental simulation, which has been shown to drive food choices. To answer this, the following questions were asked regarding the eating process mental simulation: “As you viewed this dish, the images of eating this dish come to mind” (not at all/to a great extent), “You experienced to imagine eating this dish” (few or no images of eating this dish/several images of eating this dish) and “While viewing this dish, you could imagine eating this dish” (not at all/to a great extent) [12]. The following questions were asked regarding eating outcome mental simulation: “As you view this dish, images of how you would feel after eating this dish come to mind” (not at all/to a great extent) and “While viewing this dish, you could imagine how you would feel after eating this dish” (not at all/to a great extent) [13]. We also explored the love invested by the cook (“made with love”) with two questions described by Fuchs et al. [6]: “I think the products are made with love” and “I think the products are made with passion” (strongly disagree/strongly agree).

2.4. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0. In Study 1 and Study 2, differences among the groups were tested using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc test. The results of the statistical analysis are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Food evaluation results of Study 1.

Table 2.

Food evaluation results of Study 2.

3. Results

3.1. Study 1

The results are shown in Table 1. For the questions assessing appearance, healthiness, expected goodness of taste, intention to eat, time and effort, and ‘made with love,’ the Kruskal–Wallis showed a significant difference between groups. In the case of miso soup, the Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc test results show that the machine-made group was significantly different from the homemade and control groups with a lower score in all items. In the case of the rice ball, the Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc test results show that the machine-made group scored significantly lower than the homemade and control groups in healthiness, time and effort, and ‘made with love.’ Significant difference in ‘made with love’ was observed between the handmade and control group. For expected goodness of taste, a significant difference was only found between the machine-made and control groups, with the machine-made group scoring lower than the control group. In terms of intention to eat, a significant difference was found between the control and the machine-made and homemade groups with the handmade groups scoring lower than the control. A common thread in the reviews of the two types of food is that the food appears healthier, more time-consuming, effortful, and made with love when labeled with the handmade label rather than the machine-made one. Results for the intention to eat varied by food type.

3.2. Study 2

The results are summarized in Table 2. Kruskal–Wallis tests showed significant differences between groups only for the appearance of miso soup, and the Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc test showed that the text-only recipe scored significantly higher than the photos of someone cooking the food.

No significant differences were observed between the groups in the mental simulation section in either Study 1 or Study 2.

4. Discussion

Labeling the food as being handmade had a more positive impact than it being perceived as machine-made, which is consistent with previous studies, but this was comparable only to the food names. This suggests that, contrary to the results of Abouab and Gomez [10], when only the name of the food was given, the food was perceived as having been made by hand, and the difference between the groups was mainly observed in contrast to the machine-made group. The results of Study 1 also suggest that the influence of labels relating to the food preparation process varies depending on the type of food. The only item for which the handmade group scored lower than the control group was the intention to eat the rice ball. In the case of the rice ball, the process of making rice by hand is generally involved; therefore, it is possible that the contact between the food and the person is more strongly perceived than in miso soup, which is basically cooked using utensils. Therefore, the handmade label is thought to emphasize the image of hands touching the ingredients when cooking rice balls, which influences the decrease in the intention to eat. The handmade group’s higher score for being ‘made with love’ compared to the other two groups may be for the same reason.

In Study 2, in which the presence of a cook was presented, no significant differences were found between the groups other than the appearance. This may be because the participants were able to imagine how a person would operate the recipe from the recipe text. In terms of appearance, the results were better when there was only text than when there were photos of the cook. This may reflect that the actual food photo exceeded the participants’ expectations of the finished product based on their own imagining of the cooking process.

This study suggests the need to consider the influence of possible human contact during the preparation process of the target food, and the possibility that the presence of a human may be recognized by the imagination of consumers, rather than simply just manipulating the physical presentation. Previous research has shown that labels associated with family memories are more effective in influencing customer choice [14], and that consumers prefer human (vs. robotic) labor in more symbolic consumption situations [15]. Therefore, future research should explore the influence of handmade labels and the consumer’s perception of the cooking process in more detail.

5. Conclusions

Using handmade labels and photos of the cook, we investigated the impact of human presence in the cooking process on food evaluations. Labeling a food as handmade had a more positive effect than perceiving it as machine-made, and the impact of the label seemed to vary depending on the degree of human contact in the food preparation process. It was also suggested that even if the presence of the cook is indicated by visual representations, it is necessary to consider that consumers may already imagine the presence of a person cooking from the text.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.T. and S.-i.I.; methodology, K.T. and S.-i.I.; validation, K.T.; formal analysis, K.T.; investigation, K.T.; resources, S.-i.I.; data curation, K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T.; writing—review and editing, K.T.; visualization, K.T.; supervision, S.-i.I.; project administration, S.-i.I.; funding acquisition, S.-i.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Miyagi University Research Funds for Special Purposes (1401010759).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Miyagi University Research Ethics Committee (reference number 300, 14 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the academic editors and chair of “The 5th International Electronic Conference on Foods” for providing us with the opportunity to present this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wansink, B.; Van Ittersum, K.; Painter, J.E. How descriptive food names bias sensory perceptions in restaurants. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K. The power of good intentions: Perceived benevolence soothes pain, increases pleasure, and improves taste. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2012, 3, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troye, S.V.; Supphellen, M. Consumer participation in coproduction: “I made it myself” effects on consumers’ sensory perceptions and evaluations of outcome and input product. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohle, S.; Rall, S.; Siegrist, M. I cooked it myself: Preparing food increases liking and consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 33, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; DeLong, M. American and Korean youths’ attachment to handcraft apparel and its relation to sustainability. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2017, 35, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Schreier, M.; Van Osselaer, S.M. The handmade effect: What’s love got to do with it? J. Mark. 2015, 79, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Lai, A.; Keh, H.T. Handmade vs. machine-made: The effects of handmade gifts on social relationships. Mark. Lett. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Zhao, L. Robotic chef versus human chef: The effects of anthropomorphism, novel cues, and cooking difficulty level on food quality prediction. Int. J. Social Rob. 2022, 14, 1697–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroll, R.; Schnurr, B.; Grewal, D. Humanizing products with handwritten typefaces. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 45, 648–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouab, N.; Gomez, P. Human contact imagined during the production process increases food naturalness perceptions. Appetite 2015, 91, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frizzo, F.; Dias, H.B.A.; Duarte, N.P.; Rodrigues, D.G.; Prado, P.H.M. The gnuine handmade: How the production method influences consumers’ behavioral intentions through naturalness and authenticity. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2020, 26, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, R.S.; Krishna, A. The “visual depiction effect” in advertising: Facilitating embodied mental simulation through product orientation. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 988–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Minton, E.A.; Kahle, L.R. Cake or fruit? Influencing healthy food choice through the interaction of automatic and instructed mental simulation. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guéguen, N.; Jacob, C. The effect of menu labels associated with affect, tradition and patriotism on sales. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 23, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granulo, A.; Fuchs, C.; Puntoni, S. Preference for human (vs. robotic) labor is stronger in symbolic consumption contexts. J. Consum. Psychol. 2021, 31, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).