1. Introduction

Green gram is one of the most important grain legumes in the traditional farming systems of Sri Lanka. It is one of the principal but cheapest sources of protein, and its importance as a component of the Sri Lankan diet has grown over the years. Green gram not only contains a high percentage of easily digestible protein, but its essential amino acid composition is also complementary to the staple food, rice. In addition to being an important source of human food and animal feed, green gram also plays an important role in sustaining soil fertility by improving physical properties and fixing atmospheric nitrogen in the soil.

The local production of green gram has declined over the last two decades, and 49.8% of the total green gram requirement is still being imported (Department of Customs, 2012). In this context, it is clear that increasing the production of green gram is a must in order to achieve the target of the government. Therefore, increasing the productivity of green gram has been identified as imperative in order to meet the country’s requirement and assure self-sufficiency. Moreover, the benefits of increasing green gram production would be boosting the income level of farmers and fulfilling the dietary needs of the people in the country. However, in Sri Lanka there is a large gap between the actual yield and the potential yield of green gram due to various issues—i.e., unavailability of nutrient rich soil, lack of quality seeds, unsuitable climatic factors, traditional cultivating practices, improper weed management, etc. Yield loss due to weed competition can be a major constraint on achieving potential yield in most crops, including green gram. Weed flora of green gram crop differ from region to region with soil conditions. Studying the weed diversity/dynamics is helpful for understanding the dominance or absence of a particular weed species in a cropping system, and to estimate yield loss due to weeds, and is equally important to devise better weed management strategies [

1,

2,

3].

The critical weed free period is defined as the period a crop must be kept weed free to prevent yield loss due to weed interference [

4]. The critical period of weed interference for a crop is a measure of crop, weed and environmental interactions. Crop density, soil fertility and cultivar can be adjusted to obtain advantages on the crop over weeds in the mission of competition [

5]. The critical period of weed control and crop competitiveness can be effectively utilized to develop economical and environmentally sound weed management practices [

2]. The critical period of weed competition is an important consideration in the development of appropriate weed management strategies [

6].

Information on critical weed free period (CWFP) for green gram in Sri Lanka is rare. Therefore, we aimed to find out the CWFP for green gram. It is important to provide more precise information for green gram growers about the critical periods for weed control for maximizing the yield. An investigation was carried out with objectives of determining the yield loss in green gram cultivation in the DL1 region and deciding on critical weed free periods for green gram cultivation.

2. Materials and Methods

Two field experiments were conducted during 2019/20 Maha season at Grain Legume and Oil Crop Research and Development Center (GLORDC), Angunakolapelessa which is located at Hambantota District in the Southern Province of Sri Lanka. Geographically, the experimental site was located at about 6.1660 m north latitude and 80.90310 m east longitude. The agro ecological region is DL1b (Low Country Dry Zone). The mean annual rainfall of the location is 1020 to 1050 mm, and the average annual temperature is in the range of 28–31 °C. The soil type of experiment site was Reddish Brown Earth (RBE). Soil pH was around 7.0, and the field capacity was around 35.55%. The Department of Agriculture recommended MI-5 variety, which was released in 1982, so it was used. The entire cultivation period of this variety is about 55–65 days. Moreover, this variety was selected because it is the best adapted to the region and is widely grown by farmers in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. The land was ploughed to the depth of 15–20 cm by using disk plough and harrowed two times to make a seedbed with fine tilth. Seeds were planted on well prepared levelled beds. The plot size was 3 × 4 m for experiment 1. Then, 3 × 3 m size plots were prepared for experiment 2. Three days before seed establishment, basal fertilizer was applied to the plots according to the Department of Agriculture (DOA) recommendation and incorporated into soil. Seeds were treated with the recommended fungicide. MI-5 variety was planted at 40 cm × 15 cm spacing. Two seeds were planted per hill. After 2 weeks they were thinned out to one plant per hill. All the fertilizer management practices were done according to DOA. Experimental plots were irrigated with surface irrigation. Ridge and furrow irrigation was done at 4 day intervals. After 3 weeks, irrigation was done at 7 day intervals.

2.1. Experiment 01—Determination of Yield Loss Due to Weeds in Mungbean Cultivation

Completely Randomized Block Design was used as the experimental design with three replicates. The following treatments were tested in the experiment from 2nd week to 6th week after planting.

- T1

—Sedge competition

- T2

—Grass competition

- T3

—Broad leaf competition

- T4

—Remove all weeds (No weeds)

- T5

—Sedges and broad leaves competition

- T6

—Sedges and grass competition

- T7

—Grass and broad leaves competition

- T8

—No weed control (total weedy)

Recommended cultural practices of DOA, except manual weeding, were followed. The plot size was 3 m × 4 m. The following measurements were taken in this experiment. (1) Plant stand count after one month. (2) Weed count 4 weeks after planting (WFP) and dry weight of weeds. (3) Weed count 7 weeks after planting and dry weight of weeds. (4) Biomass weight of 10 plants. (5) Number of pods per 10 plants. (6) Weight of grain yields per 10 plants. (7) Weed species in the field. Weeds were hand pulled from one square meter of each plot after 4 and 7 WAS and then classified to grasses, broad leaves and sedges. The number and dry weight (at 70 °C) of weeds of each group were recorded. Ten randomly selected green gram plants from each plot were harvested to determine biomass accumulation, number of pods and pod weight (g)/10 plants.

2.2. Experiment 02—Determination of Critical Weed Free Period in Mungbean Cultivation

The first experiment’s objective was to determine the onset of the critical weed free period (early time where competition begins). This was done by keeping the relevant fields weed free for certain lengths of time (increase the weed-free duration): weed free for 2 (T1), 3 (T2), 4 (T3), 5 (T4) or 6 (T5) weeks from planting, totally weed free (T6) and full season weedy (T7).

The second experiment’s objective was to determine the end of the critical weedy period. This was determined by allowing the crop to grow with weeds for different time periods from seeding (increase duration of competition). Weedy periods of 2 (T1), 3 (T2), 4 (T3), 5 (T4) and 6 (T5) weeks from planting were compared with T6 (full season weedy) and totally weed free (T7) groups.

The experimental design was a randomized complete block with three replicates. The natural weed populations were allowed to emerge, and weeds were removed at one-week intervals in the different treatment plots to maintain different weedy periods. The agronomic practices such as fertilization, and insect and disease management recommended by the DOA for green gram were followed. The weeds were hand weeded during the entire experimental period. The following measurements were taken in this experiment. (1) Plant stand count after one month. (2) Pod weights of 10 plants per plot. (3) Grain weights of 10 plants per plot. (4) Total grain weight per plot.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

To analyze the data, parametric statistical methods were used. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SAS 9.4, and DMRT was performed to find the best treatment combination at a p value of 0.05. To decide on the critical time for weed control, non-linear regression analysis was also performed.

3. Results and Discussion

The results of this current investigation on the identification and categorization of weed species available in GLORDC, and determination of weed free period in green gram cultivation to reduce the yield loss, are explained below.

3.1. Experiment 01—Determination of Yield Loss Due to Different Functional Groups of Weeds

The plant stand counts at 2 WAP were not different among treatments (

Table 1). Crop biomasses (weight of 10 plants) in T1, T3, T4 and T5 were 416.67, 416.67, 408.33 and 400.00 g, respectively, and these plots were free from grasses and other sedges, broad leaves and all weeds. According to the results, in which treatments caused higher biomass weights (T1, T3, T4 and T5), in those plots, yield (number of pods/10 plants, weight of grain/10 plants) was significantly higher at

p < 0.05 (

Table 1). T1 and T3 were tested, and the sedges and broad leaves caused the least biomass loss. This finding confirms that grasses are significantly more damaging than other categories of weeds. Green gram yield was shown to decrease with increasing time of weed interference for all weed species in several species-specific and mixed weed population studies, as is the case for all agronomic crops [

7].

Yield Loss Due to Weeds

Total yield loss of green gram due to weeds was 54.77%. Regarding individual effects, yield loss were 46.26%, 16.49% and 18.01% due to grasses, broad leaves and sedges, respectively. Yield loss due to the grasses and sedges combination was 46.05%; yield loss due to broad leaves and sedges was 24.46%; and yield loss due to broad leaves and grasses was 45.21%. The results show that when grasses are present alone or with other weeds, there is a cumulative effect with other weed functional groups which reduces the crop yield significantly. Everman et al. (2008) reported that the presence of weeds causes a negative effect on green gram yield [

8]. Further, Agostinho et al. (2006) reported that yield losses in plants due to weed interference varied between 74 and 92% depend on the prevailing conditions [

9]. The losses in yield of green gram pods due to weed competition ranged from 30 to 40% [

10]. These findings validate the present research findings. Naidu et al. (1982) estimated that nutrient (N, P and K) losses due to crop weed competition were 38.8, 9.2 and 23.3 kg ha

−1 respectively [

11]. Therefore, the findings emphasize that weed control is important to prevent yield and nutrient loss.

3.2. Determining the Critical Weed Free Period

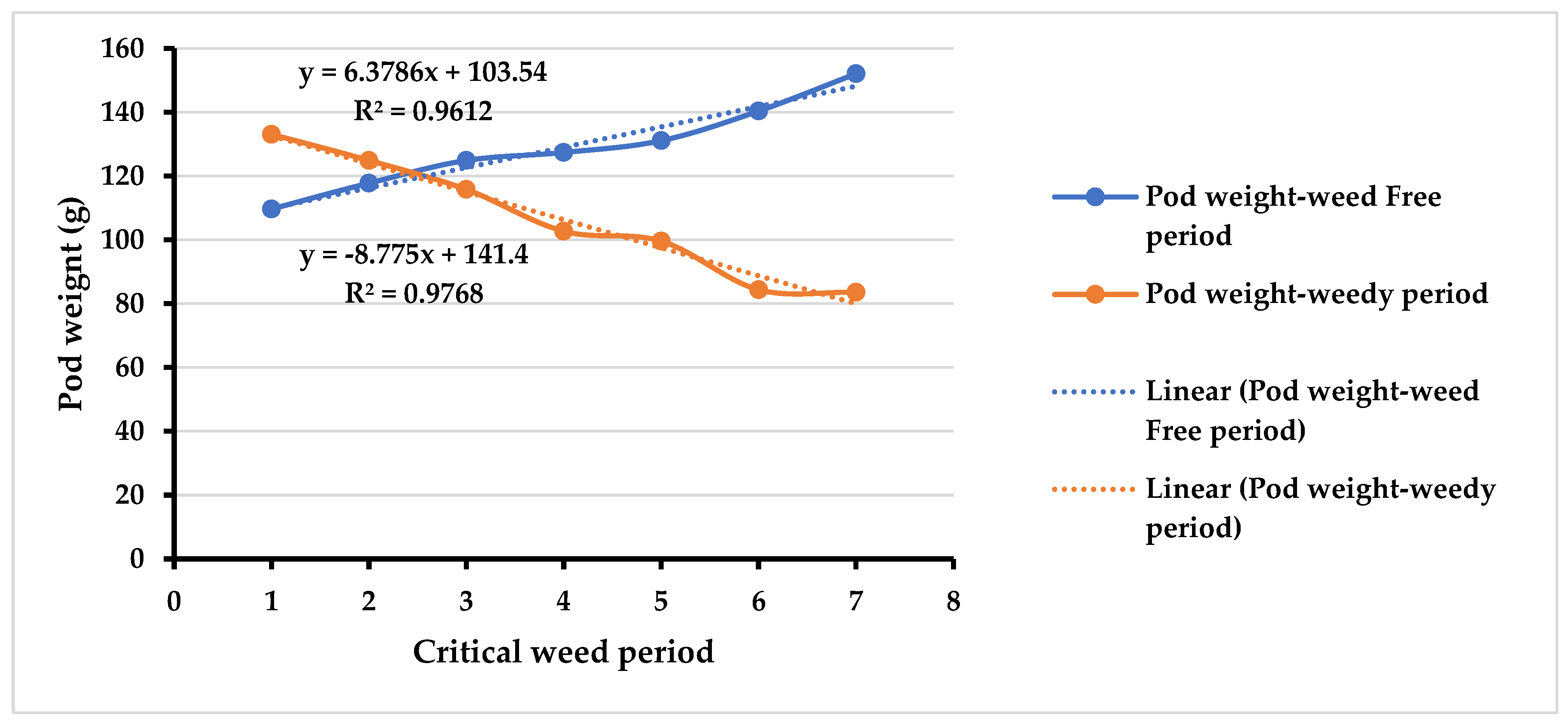

The highest value of pod weight in weed free condition was when the field was free from weeds from the planting to harvest (control 1—weed free for the whole season) because there was no competition between green gram and weeds. Having weeds the whole season (control 2) resulted in the lowest pod weight because there was competition between green gram and weeds. When increasing the weedy period or weed free period, pod yield declined or increased, respectively (

Figure 1). When the weed free period continuously increased, there was no significant difference in yield observed between T4 (weed free up to 4 WAP) and T5 (weed free up to 5 WAP). Therefore, keeping weed free until 4 WAP is the critical time for minimizing yield loss of green gram.

The highest value of total weight of pods was observed in weed free season plots (T1). Thus, it was given the highest value for total weight of pods in green gram. There was no significant difference between T6 (weeds competed up to 6 WAP) and T7 (weeds competed for the whole season—no weeding).

Weeds compete with crop plants for growth factors and impair crop growth and productivity. However, crops and weeds are different in their competition effects [

6]. Competition even for a short period after green gram emergence can harm crops and may result in severe yield losses and growth reduction, which is in most cases unrecoverable and cannot be overcome by the addition of higher levels of growth factors such as water and nutrients [

7,

12]. The factors that negatively affect green gram are short stature, low above ground canopy, slow growth and very shallow and small root systems that show aboveground in competitive environments. However, weed diversity is rarely poor in farmers’ fields, but different weed species may form weed populations one at a time. Therefore, some of the main factors that affect weed competition periods are weed composition, species’ relative densities and their spatial arrangements. Weeds are normally composites of different species dominated by broadleaf weeds; certain narrow leaf species complement the former in their competition with green gram crops. Other results indicate that the longer the weed competition period, the higher the reductions in green gram growth and yield. The lowest pod weight was obtained from plots that were weed-infested for the entire growing season [

3,

4].

4. Conclusions

Green gram yield loss due to the natural mixed weed population of the tested location was 54.77%; specifically, yield losses due to grass alone was nearly 46%, but green gram yield decreased with the interference of all weeds types. The critical weed period begins from the planting to 3 WAP. Therefore, it is recommended to maintain the weed free period till the beginning of 4 WAP. From 4 WAP onwards, there was no significant effect of weeds on crop yield.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/IECAG2021-09691/s1, Poster: Assessment of Yield Loss in Green gram (

Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek) cultivation and estimation of Weed-Free Period for Eco-friendly weed management.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally. L.P.P.D. and K.P. conceived the research idea; P.K. conducted the experiments; P.K. and K.P. wrote the manuscript; and L.P.P.D. and K.P. edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks to field staff of Grain Legume and Oil Crop Research and Development Center (GLORDC), Angunakolapelessa, for their support throughout the field experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kaur, G.; Brar, H.S.; Singh, G. Effect of weed management on weeds, nutrient uptake, nodulation, growth and yield of summer mungbean (Vigna radiata). Indian J. Weed Sci. 2010, 42, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, G.; Brar, H.S.; Singh, G. Effect of weed management on weeds, growth and yield of summer mungbean [Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek]. Indian J. Weed Sci. 2009, 41, 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, T.; Nisha, K.C.; Chopra, N.K.; Yadav, M.R.; Kumar, R.; Rathore, D.K.; Ram, H. Weed management in cowpea-A review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic, S.; Evans, S.; Blankenship, E.; Van Acker, R.; Lindquist, J.L. Critical Period for Weed Control: The Concept and Data Analysis. Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Premalal, K.P.S.B.; Sangakkara, U.R.; Van Damme, P.; Bulcke, R. Effective weed-free period of common beans in two different agro-ecological zones of Sri Lanka. Trop. Agric. Res. 1999, 11, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Swanton, C.J.; Weise, S.F. Integrated weed management: The rationale and approach. Weed Technol. 1991, 5, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimdahl, R.L. Weed-Crop Competition: A Review; Blackwell Publishing Professional: Ames, IA, USA, 2004; 220p. [Google Scholar]

- Everman, W.J.; Burke, I.C.; Clewis, S.B.; Thomas, W.E.; Wilcut, J.W. Critical period of grass versus broadleaf weed interference in peanut. Weed Technol. 2008, 22, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, F.H.; Gravena, R.; Alves, P.L.C.A.; Salgado, T.P.; Mattos, E.D. The effect of cultivar on critical periods of weed control in peanuts. Peanut Sci. 2006, 33, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasingh, D.J.; Gupta, K.M. Weed control for groundnut with herbicides. Farmer Parliam. 1973, 8, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, L.G.; Reddi, G.H.; Rajan, M.S. Nutrient uptake as influenced by crop weed competition in groundnut. Indian J. Weed Sci. 1982, 14, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.E.; Crabtree, G.; Mack, H.J.; Laws, W.D. Effect of Spacing on weed Competition in sweet corn, Snap Beans and Onions. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1973, 98, 526–529. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).