Abstract

Acetic acid bacteria (AAB) are ubiquitous wine spoilage microorganisms causing significant economic damage to winemakers. Considering difficulties in their isolation through traditional microbiological methods, it would be advantageous to detect them using molecular methods at all stages of winemaking and, thus, prevent wine spoilage. In this research, we analyzed wines, musts and grapes of 13 varieties grown in different regions of the Republic of Moldova. The DNA was extracted and analyzed via PCR using home-designed primers to detect Acetobacter aceti and Acetobacter pasteurianus. Generally, samples with no detectable amounts of AAB in either musts or wine had volatile acidity within the acceptable limits. Only one grape (Rara Neagra) had detectable amounts of AAB (A. pasteurianus) at all analyzed stages (grape, must, wine), and this sample had the highest amount of volatile acidity (2.11 g/L), exceeding the maximum acceptable limit for red wines of 1.2 g/L. A. pasteurianus was more common than A. aceti, both in musts and wines. Samples positive for AAB but containing low amounts of them in wine (Cq value > 35) did not have volatile acidity above the acceptable level. Samples that were wine-negative but must-positive for AAB had volatile acidity close to the acceptable limit. This study shows the utility of PCR diagnostics for predicting the risks of wine spoilage by AAB.

1. Introduction

Acetic acid bacteria (AAB) are very widespread spoilage microorganisms in winemaking, and they exert a negative effect on the quality of wines and require the close attention of winemakers at all stages of wine production and storage [1]. These bacteria are obligate aerobes, well adapted to high levels of sugars and ethanol [2], and they have high requirements for the presence of oxygen. When these AAB are present during winemaking, wine aging or wine storage, they metabolize ethanol to acetaldehyde using alcohol dehydrogenase and then produce acetic acid using acetaldehyde dehydrogenase [3], produce acetoin from lactic acid and ethyl acetate, and metabolize glycerol to dihydroxyacetone [4]. Moreover, they seem to affect wine quality by influencing must composition and alter the growth of yeast and lactic acid bacteria during fermentation [5].

One AAB species typically associated with grapes and must is Gluconobacter oxydans, which prefers a sugar-rich environment [3,6,7], while the ones associated with wine are Acetobacter aceti and Acetobacter pasteurianus, which prefer ethanol as a carbon source [3,6,8,9].

Acetic acid is the main component of the volatile acidity of grape musts and wines. It can be formed as a by-product of alcoholic fermentation or a product of the metabolism of acetic and lactic acid bacteria, which can metabolize ethanol and residual sugars to increase volatile acidity [10]. The presence of wild yeasts (e.g., Brettanomyces and its anamorph Dekkera, Pichia anomala, Kloeckera apiculata and Candida krusei) lead to the acetification of wine above objectionable levels [4]. Volatile acidity should be measured, at minimum after primary and malolactic fermentation, periodically through wine storage, when a film is found on a specific wine and pre-bottling [11].

The European regulation (CE 1308/2013) has set out limits for sale at 1.20 and 1.08 g/L of acetic acid for red wines and white/rose wines, respectively [3], as has the legislation of the Republic of Moldova. These limits are provided by the regulation regarding the organization of the wine market in the Republic of Moldova: GD No. 356 from 11-06-2015, p. 38/4.

Several strategies have been applied to prevent wine spoilage by microorganisms during production. Primary strategies that could be mentioned are compliance with hygiene rules and regulations at wineries, the monitoring of nutrients and residual sugars during the fermentation and at the end of it, temperature control, the use of sulphur dioxide, the use of purified enzymes for the maceration or clarification of wines, filtering wines with little concentration of sulphur dioxide and a high pH and avoiding the use of old oak barrels for aging wines.

Detection and quantification methods of the harmful microorganisms in winemaking are essential to preventing wine spoilage. These methods can be conventionally divided into two groups: microbiological and molecular methods. The conventional microbiological methods are inexpensive and simple to perform; however, they are time-consuming (1 to 2 weeks), laborious and limited in their ability to detect microorganisms in viable but non-culturable state [12] or microorganisms difficult to cultivate using laboratory media, which highlights the importance of devising alternative methods for the detection of these bacteria [7]. Also, traditional methods require trained personnel, and final identification is performed through biochemical, physiological and morphology analysis via a microscopic examination, increasing the overall cost and limiting the test to the laboratory settings [13].

Recently, direct or indirect molecular-based methods have been applied to overcome the limitations of microbiological methods [14]. Indirect methods include a traditional microbiological step, i.e., plating or enrichment, followed by the molecular identification of microorganisms. Direct methods imply detecting and identifying the microorganism directly from the sample at any stages of winemaking (grape, must, wine). Generally, direct methods have two major advantages over the indirect methods. Firstly, they can identify non-culturable microbes (those injured, viable but non-culturable or unable to grow using the chosen media). Secondly, the direct methods are much faster than indirect methods, since some microorganisms may require up to two weeks to grow [14]. In winemaking, the timely detection of these microrganisms can be crucial to prevent wine spoilage and economical losses, so the development of affordable rapid direct methods suitable for on-site analysis is a priority. Molecular biology methods, such as quantative PCR (qPCR), demonstrate high efficiency in the early detection and quantification of AAB and can be widely used in the winemaking process [15,16,17]. The quantitative real-time PCR assay used in our research is automated, sensitive and rapid since it reduces or even eliminates lengthy enrichment and isolation processes [18]. It can also quantify PCR products with greater reproducibility while eliminating the need for post-PCR processing, thus preventing carryover contamination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Samples

Grape samples were collected from different regions with Protected Geographical Indication (PGI)—Codru, Stefan Voda and Valul lui Traian (Figure 1) [19].

Figure 1.

Winemaking regions of the Republic of Moldova with Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) [19].

Three samples of each of the following grape varieties are used in this study at three stages of winemaking: Rkatiteli, Feteasca Neagra, Augustina, Ametist, Feteasca Regala, Pinot Gris, Alexandrina, Nistreana, Viorica, Cabernet Petit, Rara Neagra, Feteasca Alba and Chardonnay. They belong to four major groups: international varieties (Pinot Gris, Cabernet Petit, Chardonnay), local Georgian varieties grown in Moldova (Rkatiteli), local Moldavian–Romanian varieties (Feteasca Neagra, Feteasca Alba, Feteasca Regala, Rara Neagra) and local Moldavian new selection varieties (Augustina, Ametist, Alexandrina, Nistreana, Viorica).

Most varieties were grown in Codru PGI region, except for two varieties grown in Stefan Voda PGI region (Feteasca Neagra-Purcari and Rara Neagra) and two varieties grown in Valul lui Traian PGI region (Chardonnay and Feteasca Regala-Cahul).

Samples from 2021 were collected at three stages of winemaking: stage I—the collection and processing of grapes; stage II—must production; stage III—wine production after clarification and stabilization, before bottling but after clarification and stabilization and before bottling.

2.2. Isolation of the Wine DNA

For DNA isolation from grapes, 150 g of grapes were washed in PBS buffer for 20 min, the buffer was centrifuged at 5000× g for 20 min, the pellet was resuspended in 0.6 mL of extraction buffer and further extraction was carried out following the same protocol as must and wine samples [20].

Next, 10 ml of each wine or must sample was centrifuged at 5000× g for 30 min. The pellet was resuspended in 0.6 mL of the extraction buffer (Tris-HCl 0.2 M pH 8.0, NaCl 0.25 M, Na2EDTA 0.025 M, SDS 5% w/v) and heated at 65 °C for 1 h. All reagents were of molecular biology grade (Sigma-Aldrich). Then, 60 mg of PVP powder and a 0.5 volume of ammonium acetate solution (7.5 M) were added to the sample and incubated on ice for 30 min. After 10 min of centrifugation at 10,000× g the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube, mixed with equal volume of chloroform, vortexed and centrifuged again at 10,000× g. The upper phase was transferred to the new tube, mixed with equal volume of isopropanol and incubated at −20 °C for 30 min. The samples were centrifuged, and the pellet washed twice with 70% ethanol, air dried and dissolved in 50 μL of water; then, 2 μL of the resulting DNA solution was used for each PCR reaction. DNA quality and concentration were checked spectrophotometrically using a Genova Nano micro-volume spectrophotometer.

2.3. Real-Time PCR Amplification

Polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were conducted via the real-time PCR detection system CFX96 TouchTM BIORAD. The PCR cycling conditions were used as recommended by SYBRGreen’s manufacturer (Applied Biosystems): 95 °C for two minutes as an initial denaturation step, followed by alternations of 95 °C for 15 sec and 60 °C for 1 min for 40 cycles. For melting curve construction, samples were heated to 95 °C for 15 s, then incubated at 60 °C for 1 min (1.6 °C/sec ramp rate) and heated to 95 °C for 15 s (0.15 °C/s ramp rate). The detection of the amplified product was performed via the SYBR channel.

Previously described primers based on the sequence AB161358.1 (Acetobacter aceti genes for 16S rRNA, 16S-23S rRNA ITS and 23S rRNA) were used for A. aceti detection (P173–TTTTGAAATGTGACGCGCTTGAATG, P174–TTGCTCCCATGCACAGAAACC); previously described primers based on the sequence AJ888874.1 (Acetobacter pasteurianus partial adhA gene for alcohol dehydrogenase, P175–CCGGCGGTGATCTTCTGTTC, P176–CCGCTCTGTGCGTCAAACTT) were used for A. pasteurianus detection [20].

2.4. Calculations of Relative Cq Values

qPCR cycle threshold (Cq) values represent the number of amplification cycles required for the fluorescent signal to exceed the basal threshold level. Cq values are inversely related to the number of copies of the target gene in a sample, meaning that lower Cq values correlate with higher pathogen loads [21]. However, these values can be difficult to interpret since they have an inverse correlation with the pathogen amount. On the other hand, knowing the exact amount of pathogen may not be necessary for this particular experimental purpose; rather, a comparative study of infection load between samples may be quite informative. To obtain a visual interpretation of the infection load in different samples, we analyzed the qPCR data by subtracting the Cq value obtained for a given sample from Cq value = 40, which is the number of cycles in the PCR reaction and corresponds to the minimal amount of target gene that can be detected in this assay. Thus, the difference between the actual Cq value and Cq value of 40 indicates how much sooner the fluorescent signal exceeds the threshold level in the sample compared to the theoretical minimal amount corresponding to 40 cycles. The greater the difference, the more target gene initially there was contained in the sample, and the higher the infection load was in the sample.

2.5. Calculations of the Relative Amounts of A. pasteurianus

For the calculation of relative amounts of A. pasteurianus, the amount corresponding to 40 amplification cycles was taken as a reference point. Since the amount of the DNA doubles at each cycle, we can calculate the fold increase in the DNA amounts in different samples compared to the reference point by using 2 to the power of the calculated relative Cq value.

2.6. Measurement of the Volatile Acidity in Wine

Volatile acidity was determination via steam distillation/titration, method OIV-MA-AS313-02: R 2015, from the Compendium of International Methods of Analysis—OIV [22].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The experiments in this study were performed in triplicate. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed according to Tukey’s test at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 using the Staturphics software Centurion XVI 16.1.17 (Statgraphics Technologies, Inc., The Plains, VA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

In this work, we studied the distribution of two Acetobacter species (A. aceti and A. pasteurianus) in wine samples at different stages of winemaking (Table 1). The primers p173–174 correspond to A. aceti, and p175–176 correspond to A. pasteurianus.

Table 1.

A. aceti and A. pasteurianus qPCR Cq values and volatile acidity in grapes, musts and wines at different stages of wine production.

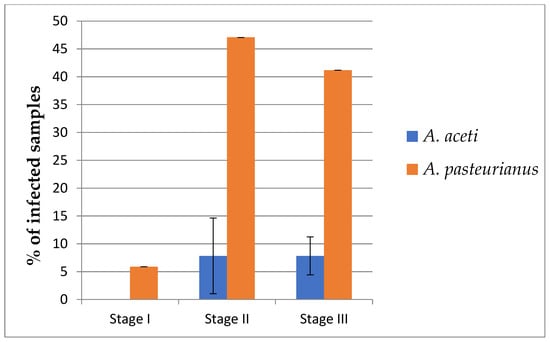

As can be inferred from Figure 2, A. pasteurianus, which infected one grape sample (5.8%), eight must samples (47%) and seven wine samples (41%), was more common than A. aceti, which infected two must samples (11.8%) and one wine sample (7.8%) (Table 1, Figure 2). Both Acetobacter species were detected predominantly in must or wine samples, with only one grape sample (5.8%) being infected with A. pasteurianus.

Figure 2.

Percentage of samples at different stages of wine production infected with A. aceti or A. pasteurianus. For each grape variety, three samples at three stages of winemaking were analyzed via PCR. Number of samples positive for infection was counted, and average and standard deviation was calculated.

A. aceti was detected at marginal value (Cq = 39.18) in Feteasca Alba in only one of three experiments; thus, it resulted in a high standard deviation value. Since A. aceti was found in only three samples at low levels (high value of Cq > 33) and apparently did not have a prominent effect on wine acidity, further discusstion will be focused on A. pasteurianus.

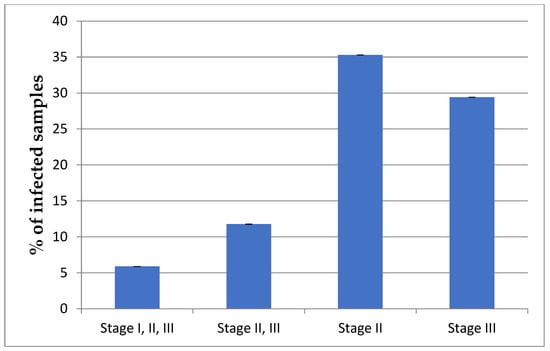

Considering the stage of winemaking at which the infection occurred, only one variety (5.8%–Rara Neagra) had detectable amounts of AAB (A. pasteurianus) at all analyzed stages, i.e., I, II, and III (I—grape, II—must, III—wine). Two samples (11.7%–Viorica and Nistreana) had detectable amounts of Acetobacter species at two stages: II and III (both must and wine). Six samples (35.2%—Ametist, Feteasca Regala-Cricova, Pinot Gris, Cabernet Petit, Feteasca Neagra-Milestii Mici (MM), Feteasca Regala-Orhei) had A. pasteurianus in must, and five samples (29.4%—Rkatiteli, Augustina, Alexandrina, Feteasca Regala-Cahul, Feteasca Alba-Straseni) had A. pasteurianus in wine (Figure 3). Three samples (Feteasca Neagra-Purcari, Feteasca Neagra-Nisporeni, Chardonnay) were negative for Acetobacter at all stages.

Figure 3.

Percentage of wines infected with Acetobacter at all three stages of wine production (I—grape, II—must, III—wine), two stages (II—must, III—wine) or single sampling stage (II—must or III—wine). For each grape variety, three samples at three stages of winemaking were analyzed via PCR. Number of samples positive for infection was counted, and average and standard deviation was calculated.

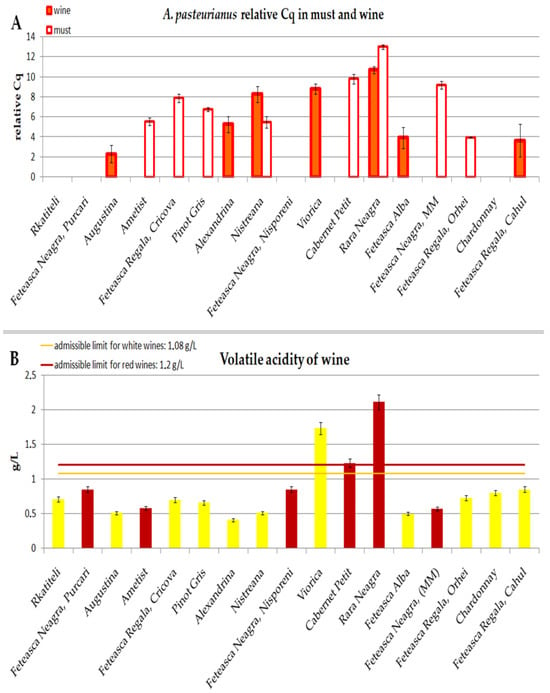

Figure 4 shows the distribution of A. pasteurianus in wine and must samples, expressed as the difference between Cq = 40 and the actual Cq values of the samples, as well as the volatile acidity of the wine samples. In general, 13 out of a total of 17 samples were infected with A. pasteurianus in at least at one stage of winemaking.

Figure 4.

Distribution of A. pasteurianus in must and wine and volatile acidity of wine samples: (A) Distribution of A. pasteurianus in must and wine, expressed as difference between Cq = 40 and the actual Cq values of the samples. Average and standard deviation for three Cq values were calculated before relative Cq calculation. Wine samples are shown in red, and must samples are shown in white; p ≤ 0.05 for both must and wine samples. (B) Volatile acidity of wine samples and admissible limits expressed as acetic acid—1.08 g/L for white wines and 1.2 g/L for red wines. Red wines are shown in dark red, and white wines are shown in yellow; p ≤ 0.05.

The acetic acid bacteria typically associated with grapes and must is Gluconobacter oxydans [3,6,7]. Nonetherless, we could detect A. pasteurianus in 8 out of the 17 analyzed must samples. Morever, some samples had a rather high content of these bacteria (Cq value about 30). This is probably due to the fact that the must was sampled at the early stage before active fermentation started. In two samples (Rara Neagra, Nistreana), A. pasterurianus is found at both Stage II for must and Stage III for wine (Figure 4A). In five samples, A. pasteurianus is found at Stage II for must but is not detected at Stage III for wine. This can be explained by the previously described fact that the acetic acid bacteria population is highly reduced during the must fermentation [23]. However, in this study, A. pasteurianus appears in the wine samples even though it had not been detected in the corresponding must samples. This is the case of Augustina, Alexandrina, Viorica, Feteasca Alba, Feteasca Regala and Cahul (Figure 4A). Interestingly, all these are white wines. A possible explanation would be that these musts were infected with a low amounts of A. pasteurianus, below the detection levels, and once fermentation was completed and the environment became favorable, their active growth started. Alternatively, the infection could occur at the winemaking site, or bacteria’s active growth could be boosted by some winemaking practices [23]. Another possibility is the presence in a low amount of some strains capable of surving in unfavorable fermentation conditions, which started active growth after fermentation ended.

Rara Neagra was affected at all three stages (grape, must and wine) and had the biggest difference in its Cq value from Cq = 40 in must and wine. Relatively high Cq differences were observed in Viorica (wine), Cabernet Petit and Feteasca Neagra-MM (must).

Two wine samples (Viorica and Rara Neagra) contained the most A. pasteurianus DNA of all samples. Since A. pasteurianus produce acetic acid and acetic acid is the main constituent of wine volatile acidity [7], the volatile acidity of the wine samples was measured.

Most wine samples had volatile acidity within the admissible limits. The volatile acidity of two wine samples (Rara Neagra and Viorica) exceeded the admissible limit. Interestingly, the same two wine samples (Rara Neagra and Viorica) had the highest contents of A. pasteurianus. Comparing Figure 4A,B, it is noticeable that the wine with highest volatile acidity, namely Rara Neagra, had the highest Cq value difference for A. pasteurianus in both wine (Cq = 29.31 ± 0.34) and must (Cq = 27.02 ± 0.20) samples, and it was also the only sample where Acetobacter was detected in grapes. Another wine exceeding the admissible limit for volatile acidity, namely Viorica, had a Cq = 31.19 ± 0.51 (high Cq difference) in wine for A. pasteurianus (Figure 4A). One sample (Cabernet Petit) had marginal volatile acidity at the admissible limit. This sample had a high Cq difference (Cq = 30.22 ± 0.48) for A. pasteurianus in must, but this microorganism was not detected in wine, possibly due to wine treatment or competition with other wine microorganisms.

These data suggest that A. pasteurianus may be at least partially responsible for increasing the volatile acidity of these wines above acceptable limits. The same conclusion was reached by the authors of [24], who established that a closely related group of Acetobacter pasteurianus predominated in isolates from wines with increased volatile acidity, as detected via the analysis of the 16S rRNA region and RAPD-PCR. Thus, A. pasteurianus can be considered the species responsible for the alteration [24].

Two samples (Feteasca Regala-Cricova and Feteasca Neagra-MM) had a relatively high Cq difference of A. pasteurianus in must, (Cq = 32.12 ± 0.41 and Cq = 30.84 ± 0.40, correspondingly) but no detectable amount in wine, and, thus, they did not exceed the volatile acidity admissible limit.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we studied the distribution of AAB in seventeen samples of thirteen varieties grown in three PGI regions of the Republic of Moldova at different stages of winemaking. A. pasteurianus was more common than A. aceti and showed more prominent correlation between the relative amount of its DNA detected in wines and the wine volatile acidity.

Acetobacter bacteria were not commonly found in grapes; in fact, only one grape sample had detectable amounts of A. pasteurianus, while A. aceti was not detected in any of the grape samples. This confirms previous observations that the AAB genus typically associated with grapes is Gluconobacter.

Only one sample, namely Rara Neagra, was infected at all three stages of winemaking, and it had the highest relative Cq in both must and wine and the highest volatile acidity.

Two wines (Viorica and Rara Neagra) with volatile acidity exceeding the admissible limits also had the highest relative amounts of A. pasteurianus DNA in wine, suggesting that A. pasteurianus could be an important wine spoilage microorganism causing increased volatile acidity in Moldovan wines.

This study shows the utility of PCR diagnostics for predicting the risks of wine spoilage by AAB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization D.Z., I.M.; methodology, D.Z., I.M., V.M., C.G., S.R., R.S., E.B., F.I., N.H.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Z., I.M., V.M., R.S.; writing—review and editing, D.Z., I.M., V.M., R.S., F.I., N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funding within bilateral research and innovation project TÜBİTAK-NARD (Turkey— Moldova, 23.80013.5107.4TR).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guillamón, J.M.; Mas, A. Acetic Acid Bacteria. In Biology of Microorganisms on Grapes, in Must and in Wine; König, H., Unden, G., Fröhlich, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komagata, K.; Iino, T.; Yamada, Y. The Family Acetobacteraceae. In The Prokaryotes; Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.–H., Stackebrands, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longin, C.; Guilloux-Benatier, M.; Alexandre, H. Design and Performance Testing of a DNA Extraction Assay for Sensitive and Reliable Quantification of Acetic Acid Bacteria Directly in Red Wine Using Real Time PCR. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Toit, M.; Pretorius, I.S. Microbial spoilage and preservation of wine: Using weapons from nature’s own arsenal—A review. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2000, 21, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Drysdale, G.S.; Fleet, G.H. The effect of acetic acid bacteria upon the growth and metabolism of yeasts during the fermentation of grape juice. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1989, 67, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyeux, A.; Lafon-Lafourcade, S.; Ribéreau-Gayon, P. Evolution of acetic Acid bacteria during fermentation and storage of wine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984, 48, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartowsky, E.J.; Henschke, P.A. Acetic acid bacteria spoilage of bottled red wine—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 125, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drysdale, G.S.; Fleet, G.H. Acetic acid bacteria in some Australian wines. Food Technol. Aust. 1985, 37, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Y.; Hoshino, K.; Ishikawa, T. The acid bacteria based on the partial sequences of 16S ribosomal RNA: The phylogeny of acetic elevation of the subgenus Gluconoacetobacter to the generic level. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1997, 61, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilela-Moura, A.; Schuller, D.; Mendes-Faia, A.; Silva, R.D.; Chaves, S.R.; Sousa, M.J.; Côrte-Real, M. The impact of acetate metabolism on yeast fermentative performance and wine quality: Reduction of volatile acidity of grape musts and wines. Appl. Microbiol.Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoecklein, B.W.; Fugelsang, K.C.; Gump, B.H.; Nury, F.S. Volatile acidity. In Wine Analysis and Production; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.W.; Ab Mutalib, N.S.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H. Rapid methods for the detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens: Principles, applications, advantages and limitations. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocolin, L.; Rantsiou, K.; Iacumin, L.; Zironi, R.; Comi, G. Molecular detection and identification of Brettanomyces/Dekkera bruxellensis and Brettanomyces/Dekkera anomalus in spoiled wines. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivey, M.L.; Phister, T.G. Detection and identification of microorganisms in wine: A review of molecular techniques. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Hierro, N.; Poblet, M.; Mas, A.; Guillamón, J.M. Enumeration and detection of acetic acid bacteria by real-time PCR and nested PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 254, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torija, M.J.; Mateo, E.; Guillamón, J.M.; Mas, A. Identification and quantification of acetic acid bacteria in wine and vinegar by TaqMan-MGB probes. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valera, M.J.; Torija, M.J.; Mas, A.; Mateo, E. Acetobacter malorum and Acetobacter cerevisiae identification and quantification by Real-Time PCR with TaqMan-MGB probes. Food Microbiol. 2013, 36, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammon, K.; Livens, S.; Pawlowsky, K.; Rawling, S.; Chandra, S. Development of real-time PCR methods for the rapid detection of low concentrations of Gluconobacter and Gluconacetobacter species in an electrolyte replacement drink. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 44, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wine Regions of Moldova. Available online: https://wineofmoldova.com/en/codru-pgi-region/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Zgardan, D.; Mitina, I.; Mitin, V.; Behta, E.; Rubtov, S.; Boistean, A.; Sturza, R.; Munteanu, M. Acetic acid bacteria detection in wines by Real-Time PCR. Sci. Study Res. Chem. Chem. Eng. Biotechnol. Food Ind. 2022, 23, 179–188. Available online: https://pubs.ub.ro/?pg=revues&rev=cscc6&num=202202&vol=2&aid=5430 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Bonacorsi, S.; Visseaux, B.; Bouzid, D.; Pareja, J.; Rao, S.N.; Manissero, D.; Hansen, G.; Vila, J. Systematic Review on the Correlation of Quantitative PCR Cycle Threshold Values of Gastrointestinal Pathogens With Patient Clinical Presentation and Outcomes. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 711809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volatile Acidity. Method OIV-MA-AS313-02. Compendium of International Methods of Analysis—OIV. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/3732/oiv-ma-as313-02.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Guillamón, J.M.; Mas, A. Acetic Acid Bacteria. In Molecular Wine Microbiology; Carrascosa, A.V., Muñoz, R., González, R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 227–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartowsky, E.J.; Xia, D.; Gibson, R.L.; Fleet, G.H.; Henschke, P.A. Spoilage of bottled red wine by acetic acid bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 36, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).