Amaranth and Chia: Two Strategic Ancestral Grains for Mexico’s Sustainability †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Production Data

2.2. Intellectual Property Information

2.3. Legal Framework

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sustainable Value of Amaranth and Chia

3.2. National Production and Production Value of Amaranth and Chia

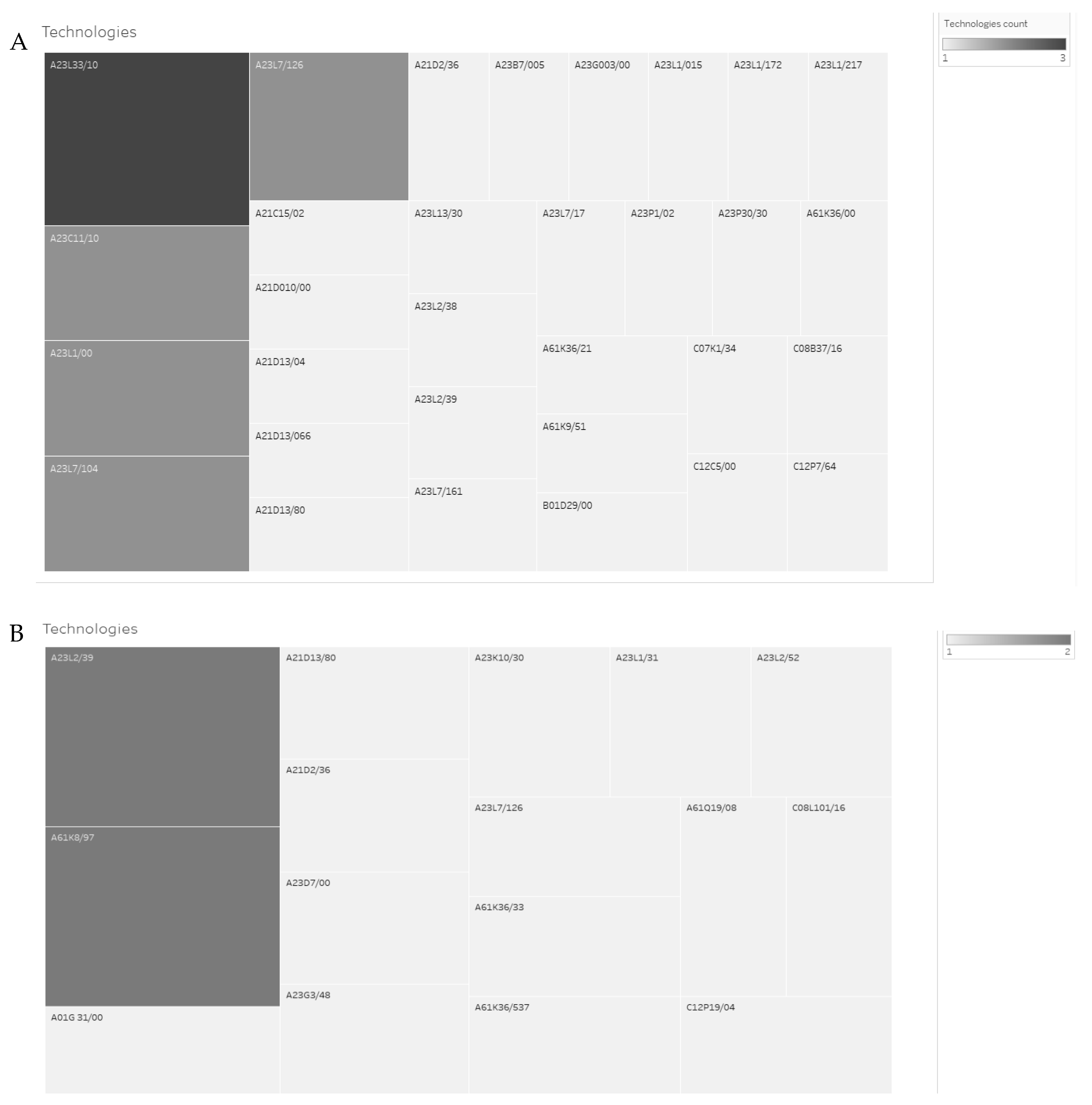

3.3. Intellectual Property Rights of Amaranth and Chia-Based Products and Processes

3.4. The Legal Framework of Chia and Amaranth Production

3.5. Future Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Alimentación y Agricultura Sostenibles [Internet]. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: http://www.fao.org/sustainability/es/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Valenzuela Zamudio, F.; Segura Campos, M.R. Amaranth, quinoa and chia bioactive peptides: A comprehensive review on three ancient grains and their potential role in management and prevention of Type 2 diabetes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 2707–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SIAP. SIACON [Software]. Available online: https://siga.impi.gob.mx/newSIGA/content/common/principal.jsfhttps://www.gob.mx/siap/documentos/siacon-ng-161430 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- IMPI. Búsqueda—SIGA [Internet]. Available online: https://siga.impi.gob.mx/newSIGA/content/common/principal.jsf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- NMX-FF-114-SCFI-2009. Diario Oficial de la Federación. Available online: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5106745&fecha=25/08/2009#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- NMX-FF-116-SCFI-2010. Available online: http://sitios1.dif.gob.mx/alimentacion/docs/NMX-FF-116-SCFI-2010_amaranto.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Mexican Law Initiative. Available online: http://sil.gobernacion.gob.mx/Archivos/Documentos/2021/04/asun_4179518_20210428_1619634670.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Mexican Law Reglas de Operación del Programa Producción para el Bienestar de la Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural para el Ejercicio Fiscal 2022. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5646225&fecha=18/03/2022#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- México sede del Primer Congreso Mundial del Amaranto [Internet]. Available online: https://masdemx.com/2018/10/amaranto-congreso-mundial-alimento-mexico/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Inauguran en San Lázaro el Curso “Evidencia Científica para la toma de Decisiones Parlamentarias” [Internet]. Available online: https://hojaderutadigital.mx/inauguran-en-san-lazaro-el-curso-evidencia-cientifica-para-la-toma-de-decisiones-parlamentarias/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valenzuela Zamudio, F.; Segura Campos, M.R. Amaranth and Chia: Two Strategic Ancestral Grains for Mexico’s Sustainability. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2022, 17, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2022017002

Valenzuela Zamudio F, Segura Campos MR. Amaranth and Chia: Two Strategic Ancestral Grains for Mexico’s Sustainability. Biology and Life Sciences Forum. 2022; 17(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2022017002

Chicago/Turabian StyleValenzuela Zamudio, Francisco, and Maira Rubi Segura Campos. 2022. "Amaranth and Chia: Two Strategic Ancestral Grains for Mexico’s Sustainability" Biology and Life Sciences Forum 17, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2022017002

APA StyleValenzuela Zamudio, F., & Segura Campos, M. R. (2022). Amaranth and Chia: Two Strategic Ancestral Grains for Mexico’s Sustainability. Biology and Life Sciences Forum, 17(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2022017002