Gender-Based Violence and the Politics of Sex Education in the United States: Expanding Medically Accurate and Comprehensive Policy and Programming

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Gender-Based Violence, Policy, and Practice Interventions

2.2. Educational Policy Intervention

2.3. Sex Education as Policy and Practice-Based Intervention

2.4. Comprehensive Sex Education

2.5. Abstinence-Only Education

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results: The Politics of Sex Education

4.1. Liberal Politics of Sex Education

4.2. Conservative Politics of Sex Education

4.3. Contemporary Normative Politics

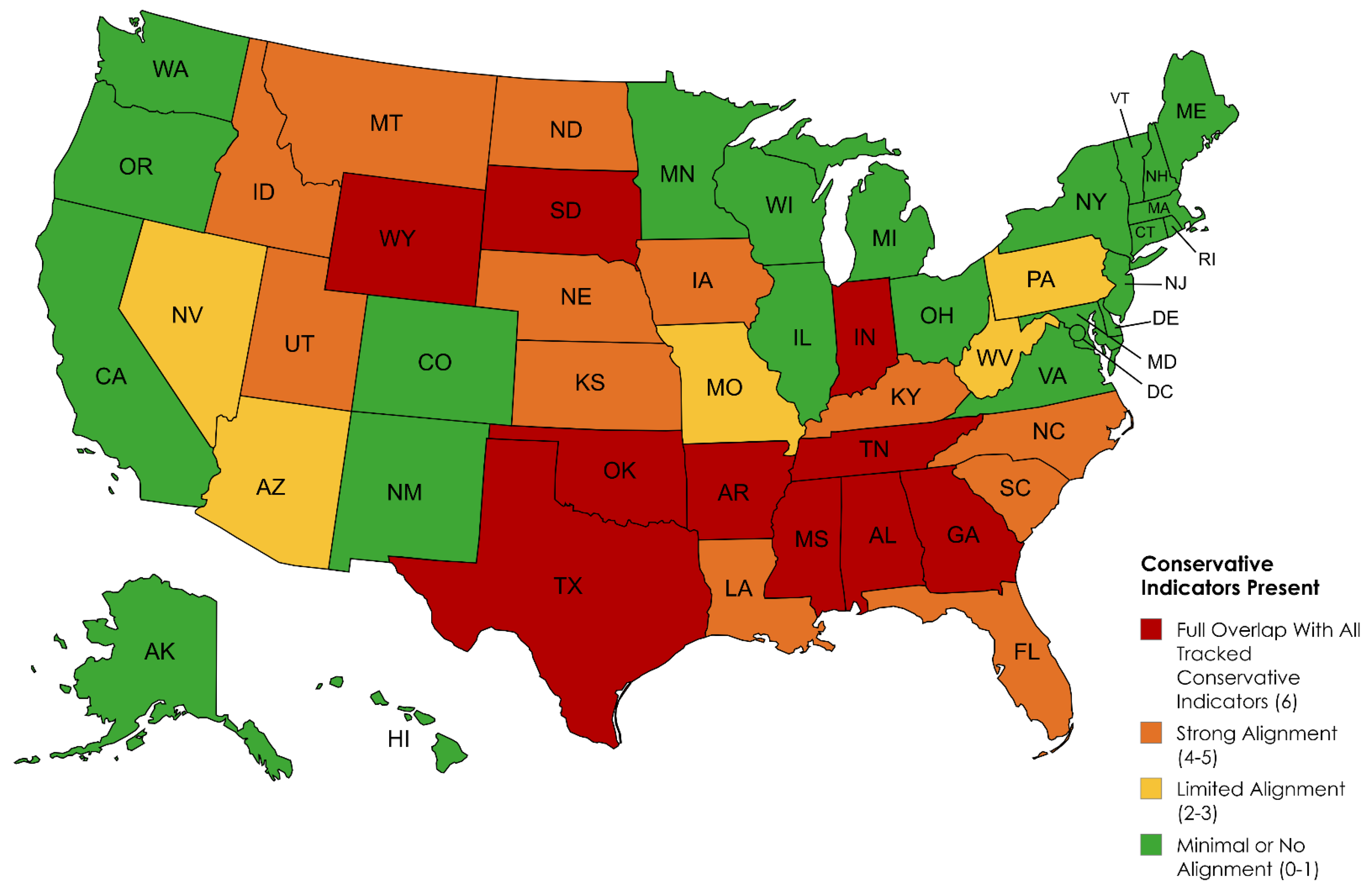

4.4. Conservative Intersections with Abstinence-Only Education Politics

| States with Abstinence-Stressing Sex Education | 2024 Republican Presidential Vote | Abortion Banned or Restricted | Death Penalty | Legal Corporal Punishment in Schools | Anti-CRT Legislation | Anti-LGBTQ+ Legislation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Arizona * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Arkansas * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Delaware | ||||||

| Florida * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Georgia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hawaii | ||||||

| Idaho | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Indiana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kentucky | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Louisiana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Maine | ||||||

| Michigan | ✓ | |||||

| Minnesota | ||||||

| Mississippi | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Missouri | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Nebraska * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| New Jersey | ||||||

| North Carolina | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| North Dakota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Ohio | ✓ | ✓ a | ||||

| Oklahoma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Oregon | ✓ a | |||||

| Rhode Island | ||||||

| South Carolina | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| South Dakota * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Tennessee | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Texas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Utah | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Washington | ||||||

| Wisconsin | ✓ | ✓ |

| States with Non-Abstinence-Stressing Sex Education | 2024 Republican Presidential Vote | Abortion Banned or Restricted | Death Penalty | Legal Corporal Punishment in Schools | Anti-CRT Legislation | Anti-LGBTQ+ Legislation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska * | ✓ | |||||

| California | ✓ a | |||||

| Colorado * | ||||||

| Connecticut | ||||||

| Illinois | ||||||

| Iowa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Kansas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Maryland | ||||||

| Massachusetts * | ||||||

| Montana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Nevada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| New Hampshire | ✓ | |||||

| New Mexico | ||||||

| New York | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ a | |||

| Vermont | ||||||

| Virginia * | ✓ | |||||

| West Virginia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Wyoming * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSE | comprehensive sex education |

| GBV | gender-based violence |

| LGBTQ+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer pr Questioning, plus related identities |

| SEL | social emotional learning |

| 1 | We acknowledge that the interpretation of such materials—including our own interpretation of the included policy texts—itself constitutes a cultural artifact. |

References

- Advocates for Youth. (2025). A K-12 sexuality education curriculum. Available online: https://www.3rs.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Albright, J. N., & Hurd, N. M. (2019). Marginalized identities, Trump-related distress, and the mental health of underrepresented college students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(3/4), 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, L. (2021). Breathing life into sexuality education. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU]. (2025). Mapping attacks on LGBTQ rights in U.S. State legislatures in 2024. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights-2024 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2022). Integrating policy into school safety theory and research. Research on Social Work Practice, 33(7), 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, A., & Gillette, E. D. (2021). Violence against Indigenous women in the United States: A policy analysis. Columbia Social Work Review, 19(1), 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen v. Kendrick, 487 U.S. 589. (1988).

- Brissett, D., Rankine, J., Mihaly, L., Barral, R., Svetaz, M. V., Culyba, A., & Raymond-Flesch, M. (2025). Addressing structural violence in school policies: A call to protect children’s safety and well-being. Journal of Adolescent Health, 76(5), 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldas, S. J., & Bensy, M. L. (2014). The sexual maltreatment of students with disabilities in American school settings. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23(4), 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camera, L. (2022, February 2). Congressional democrats target bans on teaching about racism in schools. US News & World Report. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2022-02-02/congressional-democrats-take-aim-at-efforts-to-ban-critical-race-theory (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Center for Reproductive Rights. (2025). After roe fell: Abortion laws by state. Available online: https://reproductiverights.org/maps/abortion-laws-by-state/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2004). Sexual violence prevention: Beginning the dialogue. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/43233 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: A technical package of programs, policies, and practices. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/45820 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Cislaghi, B., & Heise, L. (2020). Gender norms and social norms: Differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(2), 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88–352, 78 Stat. 241. (1964).

- Clark, L. B. (2022). Barbed-wire fences: The structural Violence of education. The University of Chicago Law Review, 89(2), 499–523. [Google Scholar]

- Coker, A. L., Bush, H. M., Clear, E. R., Brancato, C. J., & McCauley, H. L. (2020). Bystander program effectiveness to reduce violence and violence acceptance within sexual minority male and female high school students using a cluster RCT. Prevention Science, 21(3), 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Congressional Research Service [CRS]. (2024). Adolescent pregnancy: Federal prevention programs (R45183). Congressional Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- Dailard, C. (2001). Sex education: Politicians, parents, teachers and teens. Guttmacher Policy Review, 4(1), 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dailard, C. (2002). Abstinence promotion and teen family planning: The misguided drive for equal funding. The Guttmacher Report on Public Policy, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Death Penalty Information Center. (2025). State by state. Available online: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-state (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Delgado Bernal, D., Flores, A. I., Gaxiola Serrano, T. J., & Morales, S. (2023). An introduction: Chicana/Latina feminista pláticas in educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 36(9), 1627–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education v. Louisiana, 603 U.S. 1. (2024).

- Diem, S., Young, M. D., & Sampson, C. (2019). Where critical policy meets the politics of education: An introduction. Educational Policy, 33(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M. S., Thompson, S. H., M’Cormack, F. A. D., Yannessa, J. F., & Duffy, J. L. (2014). Community attitudes toward school-based sexuality education in a conservative state. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 9(2), 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Amendments of 1972, Title IX. (Pub. Law 92-318). (1972).

- Edwards, K. M., Banyard, B. L., Sessarego, S. N., Waterman, E. A., Mitchell, K. J., & Chang, H. (2019). Evaluation of a bystander-focused interpersonal violence prevention program with high school students. Prevention Science, 20(4), 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Equal Pay Act of 1963, Pub. L. 88-38. (1963).

- Evans-Winters, V. E. (2019). Black feminism in qualitative inquiry: A mosaic for writing our daughter’s body (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exec. Order No. 13950. (2020). Combating race and sex stereotyping. The White House.

- Exec. Order No. 14168. (2025). Defending women from gender ideology extremism and restoring biological truth to the Federal Government. The White House.

- Exec. Order No. 14190. (2025). Ending radical indoctrination in K-12 schooling. The White House.

- Exec. Order No. 14191. (2025). Expanding educational freedom and opportunities for families. The White House.

- Exec. Order No. 14242. (2025). Improving education outcomes by empowering parents, states, and communities. The White House.

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974, 20 U.S.C. § 1232g. (1974).

- Fava, N. M., & Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2013). Trauma-informed sexuality education: Recognising the rights and resilience of youth. Sex Education, 13(4), 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M. (2018, April 26). The Trump administration approach to teen pregnancy: “Don’t have sex”. NBC News. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-care/new-trump-teen-pregnancy-approach-stresses-abstinence-n869141 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gender Policy Council. (2023). Release of the national plan to end gender-based violence: Strategies for action. The White House. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, E. S., & Lieberman, L. D. (2021). Three decades of research: The case for comprehensive sex education. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 68(1), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graaff, K. (2021). The implications of a narrow understanding of gender-based violence. Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics, 5(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, B. J. E., Wilkerson, S. B., Pelton, L. D., Cosby, A. C., & Henschel, M. M. (2019). Title IX and school employee sexual misconduct: How K-12 schools respond in the wake of an incident. Educational Administration Quarterly, 55(5), 841–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttmacher Institute. (2021a). Evidence-based sex education: The case for sustained federal support. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/sex-education (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Guttmacher Institute. (2021b). Federally funded abstinence-only programs: Harmful and ineffective. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/factsheet/abstinence-only-programs-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Guttmacher Institute. (2025). Sex education and HIV education. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Hall, K. S., Sales, J. M., Komro, K. A., & Santelli, J. (2016). The state of sex education in the United States. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 58(6), 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellmann, J. (2018, April 20). Trump admin announces abstinence-focused overhaul of teen pregnancy program. The Hill. Available online: https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/384208-trump-admin-announces-abstinence-focused-overhaul-of-teen-pregnancy/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Hooker, L., Ison, J., Henry, N., Fisher, C., Forsdike, K., Young, F., Korsmeyer, H., O’Sullivan, G., & Taft, A. (2021). Primary prevention of sexual violence and harassment against women and girls: Combining evidence and practice knowledge: Final report and theory of change. La Trobe University. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, U. M., & Kohli, R. (2023). Silenced and pushed out: The harms of CRT-bans on K-12 teachers. Thresholds in Education, 46(1), 96–113. [Google Scholar]

- Jeanne Cleary Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act of 1990, Pub. L. 101–542. (1990).

- Jones, L., Bellis, M. A., Wood, S., Hughes, K., McCoy, E., Eckley, L., Bates, G., Mikton, C., Shakespeare, T., & Officer, A. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 380(9845), 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2018). Abstinence education programs: Definition, funding, and impact on teen sexual behavior. Available online: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/abstinence-education-programs-definition-funding-and-impact-on-teen-sexual-behavior/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Kim, E. J., Park, B., Kim, S. K., Park, M. J., Lee, J. Y., Jo, A. R., Kim, M. J., & Shin, H. N. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effects of comprehensive sexuality education programs on children and adolescents. Healthcare, 11(18), 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King County. (2025). FLASH: Sexual health education curriculum. Available online: https://www.kingcounty.gov/en/dept/dph/health-safety/health-centers-programs-services/birth-control-sexual-health/sexual-health-education/flash/about-flash (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Kirby, D. B. (2007). Emerging answers 2007: Research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Available online: https://powertodecide.org/sites/default/files/resources/primary-download/emerging-answers.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Kirby, D. B. (2008). The impact of abstinence and comprehensive sex and STD/HIV education programs on adolescent sexual behavior. Sexuality Research and Social Policy: A Journal of the NSRC, 5(3), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleski, J. (2019, January 30). Tempers flare at Capitol over comprehensive sex ed bill. Denver7. Available online: https://www.denver7.com/news/360/tempers-flare-at-colorado-state-capitol-over-controversial-comprehensive-sex-ed-bill (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Laible, J. (1997). Feminist analysis of sexual harassment policy: A critique of the ideal community. In C. Marshall (Ed.), Feminist critical policy analysis I: A perspective from primary and secondary schooling (pp. 201–215). Falmer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, M. (2019). The politics of ‘giving student victims a voice’: A feminist analysis of state trafficking policy implementation. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 14(1), 74–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, M. (2020). Title IX in the era of #Metoo: An (un)silenced majority? In J. L. Surface, & K. A. Keiser (Eds.), Women in educational leadership: A practitioner’s handbook (pp. 73–90). Word & Deed Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, M., Miles Nash, A., Mackey, H., & Young, M. D. (2025). Beyond now: Feminist politics, policy, and research futures in education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 38(8), 1095–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, M., Nickerson, A., & Saboda, J. (2021). Global displacement and local contexts: A case study of U.S. urban educational policy and practice. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 27(3), 471–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, M., & Rogers, K. (2020). When sexting crosses the line: Educator responsibilities in the support of prosocial adolescent behavior and the prevention of violence. Social Sciences, 9(9), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, M., & Rogers, K. (2023). A feminist critical heuristic for educational policy analysis: U.S. social emotional learning policy. Journal of Education Policy, 38(5), 803–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichty, L. F., Torres, J. M., Valenti, M. T., & Buchanan, N. T. (2008). Sexual harassment policies in K-12 schools: Examining accessibility to students and content. Journal of School Health, 78(11), 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyerly, E. (2024). New 2024 Title IX regulations remain in limbo for many states. Campus Security Report, 21(7), 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailhot Amborski, A., Bussières, E.-L., Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P., & Joyal, C. C. (2021). Sexual violence against persons with disabilities: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(4), 1330–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, C. (1999). Researching the margins: Feminist critical policy analysis. Educational Policy, 13(1), 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009, S. Amdt. 1511 to S. 1390. (2009).

- Mayo, C. (2022). LGBTQ youth and education: Policies and practices. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, C., Goldberg, N., & Anand, M. (2025). Disappearing data: Why we must stop Trump’s attempts to erase our communities. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. Available online: https://civilrights.org/blog/disappearing-data-why-we-must-stop-trumps-attempts-to-erase-our-communities/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Merriam, J. R. (2007). Why don’t more public schools teach sex education: A constitutional explanation and critique. William and Mary Journal of Women and the Law, 13(2), 539–592. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E., Jones, K. A., & McCauley, H. L. (2018). Updates on adolescent dating and sexual violence prevention and intervention. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 30(4), 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosley, T. (2025, March 12). What Trump’s cuts to the Department of Education mean for schools and students. NPR. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2025/03/12/nx-s1-5325731/what-trumps-cuts-to-the-department-of-education-mean-for-schools-and-students (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- National Sexual Violence Resource Center. (2025). What is sexual violence? Fact sheet. Available online: https://www.nsvrc.org/lets-talk-campus/definitions-of-terms/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- National Wraparound Initiative. (2025). Wraparound basics or what is wraparound: An introduction. Available online: https://nwi.pdx.edu/wraparound-basics/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Ochani, K., Siddiqui, A., & Ochani, S. (2024). An insight on gender-based violence. Health Science Reports, 7(1), e1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office for Civil Rights. (2023). Sexual violence and sex-based harassment or bullying in U.S. public schools during the 2020–21 school year [Data Snapshot]. U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-sexual-violence-snapshot.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Office of Tribal Justice. (2023). 2013 and 2022 reauthorizations of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). U.S. Department of Justice. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/tribal/2013-and-2022-reauthorizations-violence-against-women-act-vawa (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Olson, J. R., Benjamin, P. H., Azman, A. A., Kellogg, M. A., Pullmann, M. D., Suter, J. C., & Bruns, E. J. (2021). Systematic review and meta-analysis: Effectiveness of wraparound care coordination for children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(11), 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, M. A., & Santelli, J. S. (2007). Abstinence and abstinence-only education. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 19(5), 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, Pub. L 104–193. (1996).

- Pineda, D., & Merchan, D. (2024, March 12). Settlement in challenge to Florida’s ‘Don’t Say Gay’ law clarifies scope of LGBTQ+ restrictions. ABC News. Available online: https://abcnews.go.com/US/settlement-challenge-floridas-dont-gay-law-clarifies-scope/story?id=108042198 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Quinlivan, K. (2018). Exploring contemporary issues in sexuality education with young people: Theories in practice. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Real Education and Access for Healthy Youth Act of 2023, H.R.3583. (2023).

- Reinharz, S. (1992). Feminist methods in social research. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Republican National Committee [RNC]. (2024). 2024 GOP platform: Make America great again. Available online: https://www.donaldjtrump.com/platform (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Richie, B. E. (2012). Arrested justice: Black women, violence, and America’s prison nation. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rollston, R., Grolling, D., & Wilkinson, E. (2020a). Sexuality education legislation and policy: A state-by-state comparison of health indicators. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/2586bb2dc7d045c092eb020f43726765 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Rollston, R., Wilkinson, E., Abouelazm, R., Mladenov, P., Horanieh, N., & Jabbarpour, Y. (2020b). Comprehensive sexuality education to address gender-based violence. The Lancet, 396(10245), 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SafeBAE. (2024). SafeBAE 360° schools. SafeBAE: Safe Before Anyone Else. Available online: https://safebae.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Schneider, M., & Hirsch, J. S. (2020). Comprehensive sexuality education as a primary prevention strategy for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(3), 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, J. T. (Ed.). (1992). Sexuality and the curriculum: The politics and practices of sexuality education. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar, M. A., Edward, S., Grace, A., Pricilla, S. E., G, S., Sekhar, M. A., Edward, S., Grace, A., Pricilla, S. E., & G., S. (2024). Understanding comprehensive sexuality education: A worldwide narrative review. Cureus Journal of Medical Science, 16(11), e74788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States. (2025). Available online: https://siecus.org/siecus-state-profiles/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Smith, T. (2024, April 19). Biden administration adds Title IX protections for LGBTQ students, assault victims. NPR. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2024/04/19/1245858954/title-ix-changes-lgbtq-assault-victim-transgender-biden-administration (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Stanley, J. L., Haynes, R., Francis, G. L., Bilodeau, M., & Andrade, M. (2023). A call for saying “gay”. Psychology in the Schools, 60(12), 5076–5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromquist, N. (2013). Education policies for gender equity: Probing into state responses. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 21(65), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach (pp. 1–20). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/covid/7 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Texas Legislature. (2023). Senate Bill 17: Relating to diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives at public institutions of higher education. 88th Legislature, Regular Session. Available online: https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/88R/billtext/pdf/SB00017I.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- The Associated Press. (2025, June 24). 2024 election: Live results map. Available online: https://apnews.com/projects/election-results-2024/?office=P (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- The Heritage Foundation. (2023). Mandate for leadership: The conservative promise (Project 2025). Available online: https://static.heritage.org/project2025/2025_MandateForLeadership_FULL.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- The Washington Post. (2024, August 6). Trump claims no ties to project 2025. [Video]. Available online: https://link-gale-com.gate.lib.buffalo.edu/apps/doc/A804013297/AONE?u=sunybuff_main&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=92d098c0 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Thurmond, T. (2020). California healthy youth act: Comprehensive sexual health education. California Department of Education. Available online: https://www.cde.ca.gov/fg/fo/r8/chyattltr.asp (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Trenholm, C., Devaney, B., Fortson, K., Quay, L., Wheeler, J., & Clark, M. (2007). Impacts of four title V, Section 510 abstinence education programs. Available online: http://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/impacts-four-title-v-section-510-abstinence-education-programs-1 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Trumbull, E., Greenfield, P. M., Rothstein-Fisch, C., Maynard, A. E., Quiroz, B., & Yuan, Q. (2020). From altered perceptions to altered practice: Teachers bridge cultures in the classroom. The School Community Journal, 30(1), 243–266. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Children’s Fund, United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women & World Health Organization. (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], United Nations Children’s Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Population Fund, World Health Organization & United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. (2021). The journey towards comprehensive sexuality education: Global status report. United Nations Educational; Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. (1979). Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (Resolution 34/180). United Nations General Assembly.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS]. (2019). Laws, policies & regulations. Available online: https://www.stopbullying.gov/resources/laws (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS]. (2025). Title V state sexual risk avoidance education (SRAE) grantees. Family and Youth Services Bureau: An Office of the Administration for Children and Families. Available online: https://acf.gov/fysb/grant-funding/fysb/title-v-state-sexual-risk-avoidance-education-srae-grantees (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Justice [USDOJ] & U.S. Department of Education [USDOE]. (2016). Dear colleague letter on transgender students. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/opa/file/850986/dl (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2006). Abstinence education: Efforts to assess the accuracy and effectiveness of federally funded programs. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-07-87 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Violence Against Women Act of 1994, Pub. L. 103–322. (1994).

- Waxman, H. (2004). The content of federally funded abstinence-only education programs. U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform, Minority Staff Special Investigations Division. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzstein, C. (2005, February 11). Young people “need” new sex-education funding plan: Democrats want comprehensive program. The Washington Times. Available online: https://go-gale-com.gate.lib.buffalo.edu/ps/i.do?p=OVIC&u=sunybuff_main&id=GALE%7CA128444634&v=2.1&it=r&sid=bookmark-OVIC&asid=9a43e089 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Wies, J. R. (2015). Title IX and the state of campus sexual violence in the United States. Human Organization, 74(3), 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolgemuth, J. R., Koro-Ljungberg, M., Marn, T. M., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Dougherty, S. M. (2018). Start here, or here, no here: Introductions to rethinking education policy and methodology in a post-truth era. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women’s Congressional Policy Institute. (2025). Senate committee holds hearing on CEDAW. Available online: https://www.wcpinst.org/source/senate-committee-holds-hearing-on-cedaw/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2023, May 18). Comprehensive sexuality education. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/comprehensive-sexuality-education (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- World Population Review. (2025). Critical race theory ban states 2025. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/critical-race-theory-ban-states (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Yeban, J. (2024). State laws regarding corporal punishment. Find Law. Available online: https://www.findlaw.com/education/student-conduct-and-discipline/state-laws-regarding-corporal-punishment.html (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Yerger, W., & Gehret, C. (2011). Understanding and dealing with bullying in schools. The Educational Forum, 75(4), 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. D., & Diem, S. (Eds.). (2024). Handbook of critical educational research: Qualitative, quantitative, and emerging approaches. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lemke, M.; Jekayinoluwa, J.; Petko, D.; Sharma, V.; LiPuma, K. Gender-Based Violence and the Politics of Sex Education in the United States: Expanding Medically Accurate and Comprehensive Policy and Programming. Youth 2025, 5, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040127

Lemke M, Jekayinoluwa J, Petko D, Sharma V, LiPuma K. Gender-Based Violence and the Politics of Sex Education in the United States: Expanding Medically Accurate and Comprehensive Policy and Programming. Youth. 2025; 5(4):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040127

Chicago/Turabian StyleLemke, Melinda, Joyce Jekayinoluwa, Danielle Petko, Vandana Sharma, and Kelsey LiPuma. 2025. "Gender-Based Violence and the Politics of Sex Education in the United States: Expanding Medically Accurate and Comprehensive Policy and Programming" Youth 5, no. 4: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040127

APA StyleLemke, M., Jekayinoluwa, J., Petko, D., Sharma, V., & LiPuma, K. (2025). Gender-Based Violence and the Politics of Sex Education in the United States: Expanding Medically Accurate and Comprehensive Policy and Programming. Youth, 5(4), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040127