Identity Construction and Digital Vulnerability in Adolescents: Psychosocial Implications and Implications for Social Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Adolescence and Identity Development

1.2. Social Media and Digital Interaction

1.3. Cyberbullying

1.4. Relevance for Social Work Interventions

1.5. Research Questions

- How does social media use influence adolescents’ identity development, self-concept, self-esteem, and body image?

- What evidence exists regarding the prevalence, characteristics, and psychosocial consequences of cyberbullying among adolescents?

- What risk and protective factors have been identified in relation to social media use, emotional well-being, and cyberbullying experiences?

- What implications do these findings have for social work practice, including prevention, support, and intervention strategies?

1.6. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

- Scopus, for its international and multidisciplinary coverage.

- Google Scholar, for its accessibility and wide reach.

- SciELO, for its focus on Latin American scientific literature.

- Dialnet, for its relevance in educational and social research in Spanish.

- Spanish: “social networks AND identity AND adolescent AND cyberbullying”; “adolescent identity AND cyberbullying”.

- English: ‘social AND networks AND adolescents AND identity AND cyberbullying’; ‘cyberbullying AND adolescents’; ‘social networks AND cyberbullying’.

- Adolescent identity, focusing on self-concept, self-esteem, body image, and interpersonal relationships.

- Cyberbullying, considering prevalence, characteristics, psychological effects, and relationship with social media use.

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Publications between 2019 and 2024.

- Language: Spanish or English with full text available.

- Target population: adolescents.

- Content: studies addressing at least one of the following aspects: influence of social media on identity, self-perception, cyberbullying, or related emotional and social effects.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Non-scientific, duplicate, or studies outside the established period

- Not focused on the adolescent population or without full access to the text.

- Not directly related to social media, identity, body image, or cyberbullying.

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

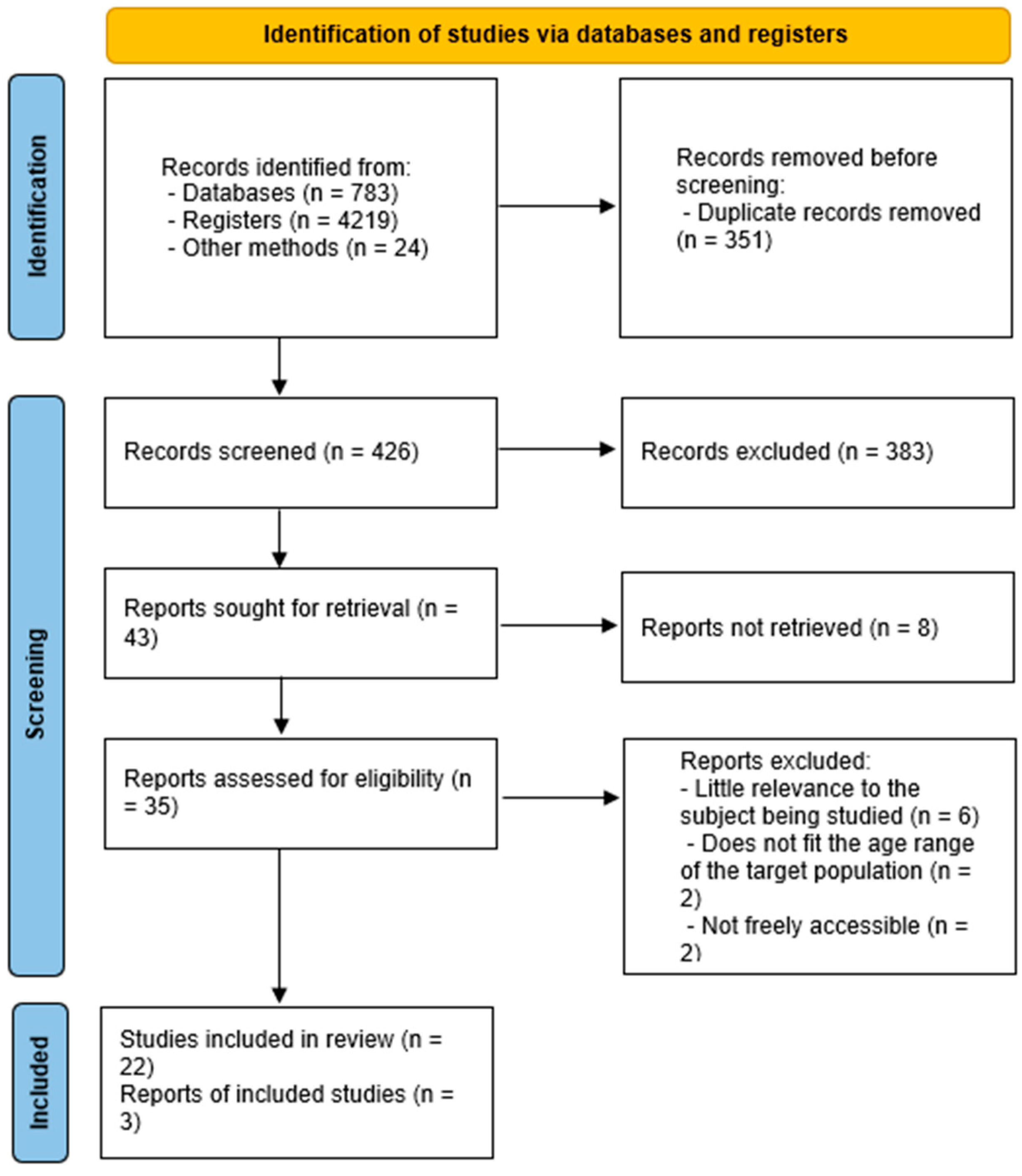

2.3. Data Selection and Extraction Process

- Initial review of titles and abstracts to eliminate duplicate or irrelevant articles.

- Evaluation of full texts to verify compliance with inclusion criteria.

- Extraction and coding of relevant information on variables of interest: identity, self-concept, self-esteem, body image, cyberbullying, and gender differences

- Qualitative synthesis and thematic organization of findings to identify patterns, trends, and research gaps.

Reviewer Involvement and Data Verification

2.4. Data Availability

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Identity, Self-Perception, and Body Image

3.2. Social Comparison and Digital Pressure

3.3. Mental Health Impacts

3.4. Cyberbullying: Normalized Violence with Significant Impact

4. Discussion

4.1. Identity Construction in Adolescence

4.2. Digital Reconfiguration of Identity and Social Validation

4.3. Emotional Consequences of Digital Exposure

4.4. Cyberbullying and Adolescent Vulnerability

4.5. Implications for Future Research

- Future studies should investigate how digital exposure shapes adolescent identity and self-esteem differently according to gender, age, and social context.

- Research should examine the influence of social media algorithms, online feedback mechanisms, and platform-specific features on identity formation, body image, and mental health.

- Coping strategies employed by adolescents to navigate social comparison, aesthetic pressures, and cyberbullying should be studied, using longitudinal, qualitative, and mixed-method designs to capture long-term effects and subjective experiences.

- Direct participation of adolescents in research is recommended to better understand their perspectives, agency, and resilience in digital spaces.

- Social workers, educators, and mental health professionals should integrate gender-sensitive approaches when designing interventions that address social media pressures and cyberbullying.

- Digital literacy programs can be implemented in schools to enhance critical thinking, emotional regulation, and safe online behaviors.

- Family-focused interventions that strengthen cohesion, communication, and support can buffer the negative effects of digital exposure on adolescent mental health and self-perception.

- Peer-based programs promoting empathy, prosocial behavior, and bystander intervention can reduce the prevalence and impact of cyberbullying.

- Policymakers should develop guidelines and regulations that promote safe and inclusive digital environments for adolescents, including platform accountability for harmful content and bullying.

- National and regional initiatives can support school-based mental health programs and digital literacy curricula, particularly targeting vulnerable populations.

- Policies should encourage collaboration between schools, families, and social services to create multi-level protective networks for adolescents navigating online spaces.

4.6. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Athanasiou, K., Melegkovits, E., Andrie, E. K., Richardson, C., Tsitsika, A., & Kafetzis, D. (2018). Cross-national aspects of cyberbullying victimization among 14–17-year-old adolescents across seven European countries. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Quiroz, J. M., Pérez Gómez, L., & Martínez Díaz, A. (2023). Relación entre bullying, ciberbullying y autoestima: Prevalencia y factores asociados en adolescentes de Colombia. Zona Próxima, 38, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmeier, O., & Cardozo, G. (2024). Bullying y Ciberbullying en “post-pandemia”: Un estudio con adolescentes escolarizados de la ciudad de Córdoba. Revista de Psicología, 20(40), 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C. P. (2019). Predicting cyberbullying: Research, theory, and intervention. Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal Párraga, A. P., Tello Mayorga, L. E., Cintia Guisela, A. V., Troya, L. A., Pluas Muñoz, A. M., Mario Efren, C. Q., & Jumbo García, K. J. (2025). El impacto del uso de redes sociales en la autoestima de adolescentes. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 9(1), 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañas, V., Trujillo, M., & Brea, A. (2021). Ciberacoso entre adolescentes: Concepto, factores de riesgo y consecuencias sobre la salud mental. XXII Congreso Virtual Internacional de Psiquiatría, Psicología y Salud Mental. Available online: https://psiquiatria.com/congresos/pdf/1-8-2021-10-PON35.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Cabrera, M. C., Larrañaga Rubio, E., & Yubero, S. (2024). Variables sociofamiliares en adolescentes ciberacosadores: Prevención e intervención desde el Trabajo Social. Alternativas. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 31(2), 378–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Vidal, P., Díaz-López, A., & Sabariego-García, J. A. (2023). Relación entre el uso de Instagram y la imagen corporal de los adolescentes. Apuntes de Psicología, 41(2), 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campodónico, N., & Aucapiña, I. E. (2024). Revisión sistemática sobre la influencia de las redes sociales en la autoestima de los adolescentes. Psicología Unemi, 8(15), 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos Garay, J., Godoy Sánchez, L., & Mesquita Ramírez, M. (2023). Ciberbullying en adolescentes que consultan en un hospital pediátrico de referencia: Frecuencia y formas de victimización. Pediatría (Asunción), 50(2), 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catagua-Meza, G. D., & Escobar-Delgado, G. R. (2021). Ansiedad en adolescentes durante el confinamiento (Covid 19) del barrio Santa Clara—Cantón Manta—2020. Polo Del Conocimiento: Revista Científico—Profesional, 6(3), 2094–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prete, A., & Redon Pantoja, S. (2020). Las redes sociales virtuales: Espacios de socialización y definición de identidad. Psicoperspectivas Individuo Y Sociedad, 19(1), 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Mora, R., Vargas-Jiménez, E., Castro-Castañeda, R., Medina-Centeno, R., & Huerta-Zúñiga, C. G. (2019). Ciberacoso como factor asociado al malestar psicológico e ideación suicida en adolescentes escolarizados mexicanos. Acta Universitaria, 29, e2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso Vázquez, T., Rubio Hurtado, M. J., & Vilà Baños, R. (2019). Factores asociados a la cibervictimización en adolescentes españoles de 12–14 años. Health and Addictions/Salud y Drogas, 19(1), 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D., Finn, S., & Steptoe, A. (2021). How leisure activities affect health: A narrative review and multi-level theoretical framework of mechanisms of action. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(4), 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijóo, S., Foody, M., O’Higgins Norman, J., Pichel, R., & Rial, A. (2021). Cyberbullies, the cyberbullied, and problematic internet use: Some reasonable similarities. Psicothema, 33(2), 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Calatayud, V., & Espinosa, M. P. P. (2021). Role-based cyberbullying situations: Cybervictims, cyberaggressors and cyberbystanders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Mares, M. (2019). Reseña del libro Metodología de la investigación: Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta, por R. Hernández-Sampieri & C. Mendoza. Revista Universitaria Digital de Ciencias Sociales (RUDICS), 10(18), 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henares-Montiel, J., Benítez-Hidalgo, V., Ruiz-Pérez, I., Pastor-Moreno, G., & Rodríguez-Barranco, M. (2022). Cyberbullying and associated factors in member countries of the European Union: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies with representative population samples. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiva Castillo, J., Rabanal Carrasco, M., Cabrera Palma, D., Canales Abarca, J., Gormaz Aguirre, M., Meza Espinoza, J., & Morandé Morales, V. (2023). Conductas sociales y de salud de la adolescencia representadas en TikTok. Enfermería: Cuidados Humanizados, 12(1), e3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, A., Sádaba, C., & Feijoo, B. (2024). Exposición de los adolescentes al marketing de influencers sobre alimentación y cuidado corporal. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 57, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid López, E. J., Valdés Cuervo, Á. A., Urías Murrieta, M., Torres Acuña, G. M., & Parra-Pérez, L. G. (2019). Factores asociados al ciberacoso en adolescentes: Una perspectiva ecológico-social. Perfiles Educativos, 42(167), 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M., & Sánchez, E. (2016). Construcción de la identidad y uso de redes sociales en adolescentes de 15 años. PsicoEducativa: Reflexiones y Propuestas, 2(4), 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, B. M. (2020). El papel de las emociones en la adicción y el uso problemático al smartphone en adolescentes: Una revisión de la literatura [Trabajo de fin de máster, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya]. Available online: https://openaccess.uoc.edu/items/5c643d95-34e1-4ca4-8ce6-b416eed190ad?locale=es (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Montes Castillo, M., Medina García, E. M., & León Duarte, G. A. (2024). Redes sociales y comparación social en adolescentes de México: Implementación de modelo interdisciplinar. Miguel Hernández Communication Journal, 15, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduchowicz, R. (2021). Adolescentes, participación y ciudadanía digital. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Órfão, M., & Días, P. (2024). The impact of TikTok on the body image and self-esteem of Portuguese adolescent boys. Comunicar, 32(79), 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J. R. (2022). Variables asociadas al fenómeno del ciberbullying en adolescentes colombianos. Revista de Psicología, 41(1), 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes Barrera, K. S. (2024). Respuestas conductuales de estrés ante los estereotipos de redes sociales digitales en adolescentes. Educación y Salud Boletín Científico Instituto de Ciencias de la Salud Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, 13(25), 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizo-Vélez, J. R. (2023). Impacto de las redes sociales en la comunicación entre adolescentes: Estudio de caso en la Unidad Educativa “Pedro Zambrano Barcia” de Portoviejo, Ecuador. Revista Estudios del Desarrollo Social: Cuba y América Latina, 11(1), 62–75. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2308-01322023000100006 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A. J., Mero, O., Solera, E., Herrera-López, M., & Calmaestra, J. (2020). Prevalence and psychosocial predictors of cyberaggression and cybervictimization in adolescents: A Spain-Ecuador transcultural study on cyberbullying. PLoS ONE, 15(11), e0241288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, G. A. B. (2015). Repercussões das redes sociais na subjetividade: Narcisismo, felicidade e elaboração psíquica. Psicologia em Estudo, 20(3), 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio Hernández, F. J., González Calahorra, E., & Olivo Franco, J. L. (2024). Adolescentes en la era digital: Desvelando las relaciones entre las redes sociales, el autocontrol, la autoestima y las habilidades sociales. Ciencia y Educación, 8(3), 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrate-González, S., Sánchez-Rojo, A., Andrade-Silva, L.-E., & Muñoz-Rodríguez, J.-M. (2023). Onlife identity: The question of gender and age in teenagers’ online behaviour. Comunicar, 31(75), 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, B. M. E., Batista, D., & Valderrama de Amaya, D. (2022). Las redes sociales como herramientas interactivas a nivel superior. Societas, 24(2), 108–127. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9534207 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Torrecillas Lacave, T., Vázquez-Barrio, T., & Suárez-Álvarez, R. (2022). Experiencias de ciberacoso en adolescentes y sus efectos en el uso de internet. Revista ICONO 14. Revista científica de Comunicación y Tecnologías emergentes, 20(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela Guzmán, M. A., Juárez Vásquez, M. A., Orenos Pineda, G. L. T., Santiso Rodríguez, C. M., & Cardona Monroy, M. I. (2024). Ciberbullying: Manifestaciones comunes y roles de género en los actores. Revista Ciencia Multidisciplinaria CUNORI, 8(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, A. G., & Brustenga, M. S. I. (2010). La gestión de la identidad digital: Una nueva habilidad informacional y digital. BiD: Textos Universitaris de Biblioteconomia i Documentació, 24, 1–15. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3308302 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 56(5), 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, H. C., & Scott, H. (2016). #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence, 51(1), 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2024). Adolescents: Health risks and solutions. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescents-health-risks-and-solutions (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Wright, M. F., & Wachs, S. (2024). The Role of Parental Mediation in the Associations Among Cyberbullying Bystanding, Depression, Subjective Health Complaints, and Self-Harm. Youth & Society, 57(2), 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/Year | Title | Study Type/Instrument | Sample | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Bernal Párraga et al., 2025) | The impact of social media use on adolescents’ self-esteem | Mixed. Descriptive–correlational | 250 adolescents (12–18 years) | Intensive use affects self-esteem due to social comparison. In girls, higher aesthetic pressure. Positive social interactions improve self-esteem. |

| (Campodónico & Aucapiña, 2024) | Social media and self-esteem: Systematic review | Systematic review, qualitative | 10 studies (2019–2023) | Consequences: anxiety, bullying, insomnia, psychosomatic symptoms. Greater impact on females. |

| (Camacho-Vidal et al., 2023) | Relationship between Instagram use and adolescents’ body image | Quantitative, cross-sectional | 95 adolescents (11–19 years) | Instagram generates aesthetic pressure, especially in girls. Likes affect self-esteem. Strong association with anxiety and insecurity. |

| (Del Prete & Redon Pantoja, 2020) | Online social networks: Spaces for socialization and identity definition | Qualitative. 32 ethnographic interviews | Adolescents (12–18 years) | Networks serve to define the digital “self.” Performative identity, anxiety due to presentation. Risk: low self-esteem, mental health issues. |

| (Leiva Castillo et al., 2023) | Social and health behaviors of adolescents represented on TikTok | Qualitative. Content analysis | 50 videos of adolescents (13–19 years) | Stereotypes, use of filters, social pressure regarding appearance. Content normalizes risk behaviors. Greater exposure among girls. |

| (López-Martínez et al., 2024) | Adolescents’ exposure to influencer marketing on nutrition and body care | Quantitative-exploratory. Surveys | 1055 adolescents (11–17 years) | Influencers affect self-esteem and decisions. Girls receive more aesthetic content. Harmful advertising affects body image. |

| (Miranda, 2020) | The role of emotions in smartphone addiction and problematic use among adolescents | Systematic qualitative review | 13 studies | Problematic use is associated with low self-esteem and anxiety. Protective factors: high self-esteem and good family relationships. |

| (Montes Castillo et al., 2024) | Social media and social comparison among adolescents | Quantitative, longitudinal | 416 adolescents (12–17 years) | Negative social comparison, body distortion, anxiety, and eating disorders. Identity construction adapted to digital standards. |

| (Órfão & Días, 2024) | The impact of TikTok on body image and self-esteem | Qualitative exploratory. 30 interviews | 30 male adolescents (10–19 years) | TikTok generates male social pressure. Some content improves self-esteem; other content promotes anxiety and body vigilance. |

| (Reyes Barrera, 2024) | Behavioral stress responses to digital stereotypes | Narrative review | Scientific literature (12–18 years) | Networks reinforce unattainable standards. Effects: body dissatisfaction, anxiety, depression. Girls are more vulnerable. |

| (Rizo-Vélez, 2023) | Impact of social media on adolescent communication | Quantitative | 250 adolescents (13–18 years) | Facebook is the main communication medium. Networks influence identity and pressure to maintain an idealized profile. |

| (Rubio Hernández et al., 2024) | Unveiling the relationships between social media, self-control, self-esteem, and social skills | Quantitative, descriptive-correlational | 158 adolescents (12–17 years) | No direct relationship between use and self-esteem, but related to self-control. Networks used for avoidance, concentration problems, and isolation. |

| (Serrate-González et al., 2023) | Onlife identity: Gender and age in adolescent behavior on social networks | Quantitative. Ex post facto | 15 adolescents (12–18 years), 31 centers | Networks influence digital identity and social acceptance. Girls use more filters and show themselves; boys prefer anonymity. |

| Author/Year | Title | Type of Study/Instrument | Sample | Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Donoso Vázquez et al., 2019) | Factors associated with cybervictimization in Spanish adolescents aged 12–14. | Quantitative. Survey. | 4.536 adolescents (Mean age: 15) | Cyber-aggressors are often also victims. Excessive use and anonymity increase cyberbullying. 44.1% experienced some form. |

| (Bachmeier & Cardozo, 2024) | Bullying and Cyberbullying: “Post-Pandemis”. A study with school adolescents from Córdoba. | Quantitative, descriptive. Test. | 745 adolescents (13–19 years) | Cyberbullying increased after the pandemic. Family and school environment influence. Bystanders also play a role. Prosocial deficit increases victimization. |

| (Cabañas et al., 2021) | Cyberbullying among adolescents: concept, risk factors, and consequences on mental health. | Systematic review. | Studies (Dec. 2020–Jan. 2021) | Linked to low empathy, family violence, and social anxiety. Consequences: depression, suicidal ideation, poor academic performance. |

| (Domínguez-Mora et al., 2019) | Cyberbullying as a factor associated with psychological distress and suicidal ideation in Mexican adolescents. | Quantitative explanatory, cross-sectional. | 1.676 adolescents (12–17 years) | Cyberbullying participation is associated with psychological distress and suicidal ideation. Greater impact on females. |

| (Cabrera et al., 2024) | Socio-family variables in cyberbullying adolescents: prevention and intervention from Social Work. | Quantitative cross-sectional. Questionnaires. | 1.029 adolescents (11–19 years) | Pleasant emotions towards bullying increase likelihood. Early family cohesion protects; conflicts in mid-adolescence increase risk. |

| (Madrid López et al., 2019) | Factors associated with cyberbullying in adolescents: An ecological-social perspective. | Quantitative. Logistic regression. | 1.488 (15–18 years) | Family violence and school bullying have influence. Protective factors: empathy, family support, community, and school. |

| (Torrecillas Lacave et al., 2022) | Experiences of cyberbullying in adolescents and its effects on internet use. | Mixed. Survey and focus groups. | 865 adolescents (12–18 years) | Females more affected. Adopt self-censorship and reduce online participation due to fear and insecurity. |

| (Valenzuela Guzmán et al., 2024) | Cyberbullying: Common manifestations and gender roles among actors. | Quantitative cross-sectional. Questionnaires. | Adolescents (12–16 years) | Girls: more cybervictimization (12.67%). Boys: more cyberaggression (2.67%). Common forms: teasing, impersonation, exclusion. |

| (Domínguez-Mora et al., 2019) | Variables discriminating the profile of cyberbullies in Mexican adolescents. | Quantitative. Ex post facto, cross-sectional. | 1.681 adolescents (12–17 years) | Aggressors show conflictive communication with parents and negative attitudes. Victims report more family and academic support. |

| (Pacheco, 2022) | Variables associated with the phenomenon of cyberbullying in Colombian adolescents. | Quantitative. | 1.080 adolescents (10–19 years) | Risk factors: excessive mobile use, being female. With increasing age: less victimization, higher likelihood of becoming aggressor. |

| (Álvarez Quiroz et al., 2023) | Relationship between bullying, cyberbullying, and self-esteem in Colombian adolescents. | Quantitative, descriptive–correlational. | 460 adolescents (12–18 years) | Low self-esteem linked to greater cybervictimization. Medium self-esteem also implies risk. |

| (Carlos Garay et al., 2023) | Cyberbullying in adolescents in a pediatric hospital: frequency and forms. | Observational, descriptive, prospective. Questionnaire. | 406 adolescents (12–18 years) | 22.5% reported cyberbullying. Forms: exclusion (54.2%), persistent messages (42.3%), jokes (32.8%), humiliating images (16.2%). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elvira-Zorzo, M.N.; Bayona Gómez, P. Identity Construction and Digital Vulnerability in Adolescents: Psychosocial Implications and Implications for Social Work. Youth 2025, 5, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040119

Elvira-Zorzo MN, Bayona Gómez P. Identity Construction and Digital Vulnerability in Adolescents: Psychosocial Implications and Implications for Social Work. Youth. 2025; 5(4):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040119

Chicago/Turabian StyleElvira-Zorzo, María Natividad, and Paula Bayona Gómez. 2025. "Identity Construction and Digital Vulnerability in Adolescents: Psychosocial Implications and Implications for Social Work" Youth 5, no. 4: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040119

APA StyleElvira-Zorzo, M. N., & Bayona Gómez, P. (2025). Identity Construction and Digital Vulnerability in Adolescents: Psychosocial Implications and Implications for Social Work. Youth, 5(4), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040119