Positive Youth Development Revisited: A Contextual–Theoretical Approach for Disadvantaged Youth in Singapore

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Youth Study in Singapore

1.2. Aims of This Study

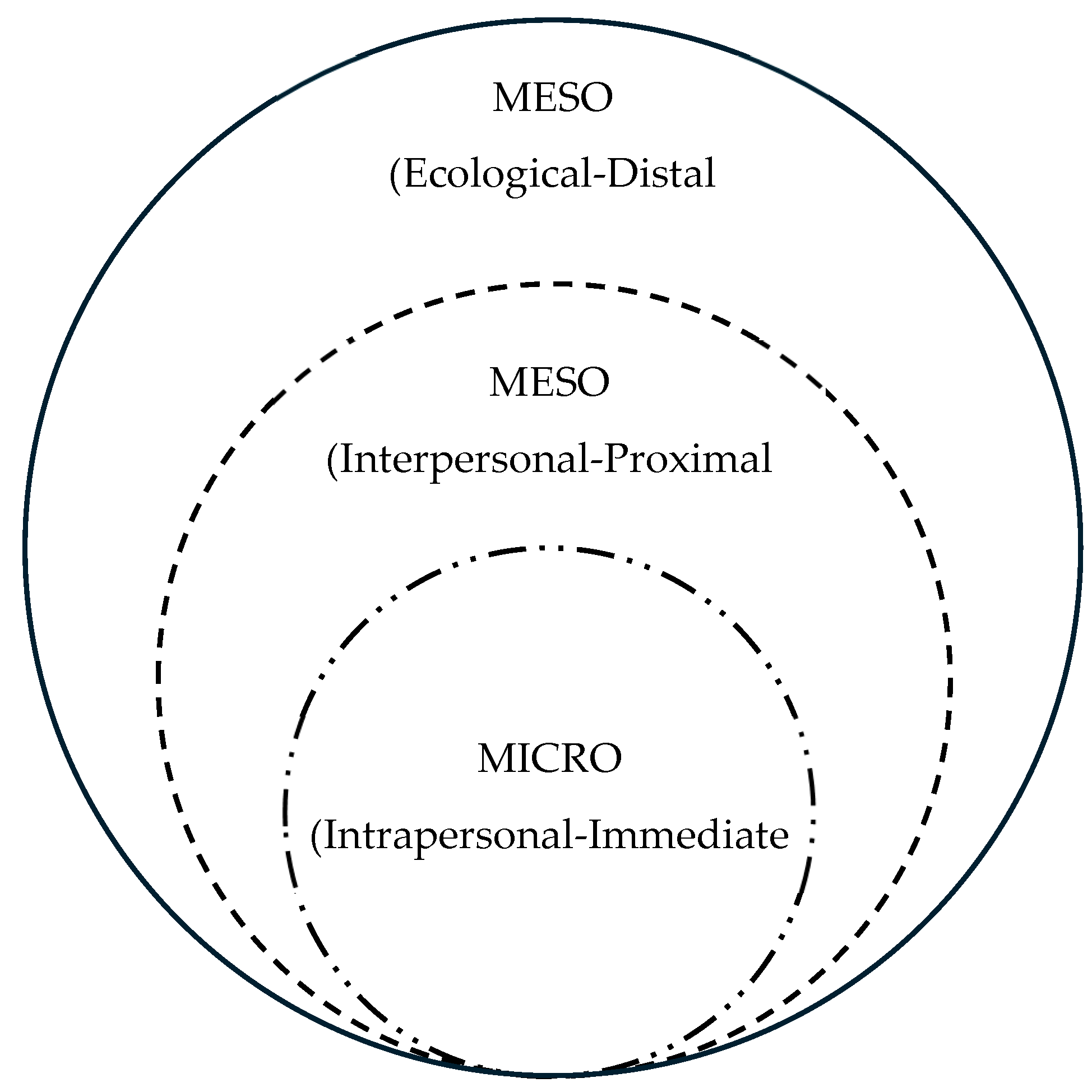

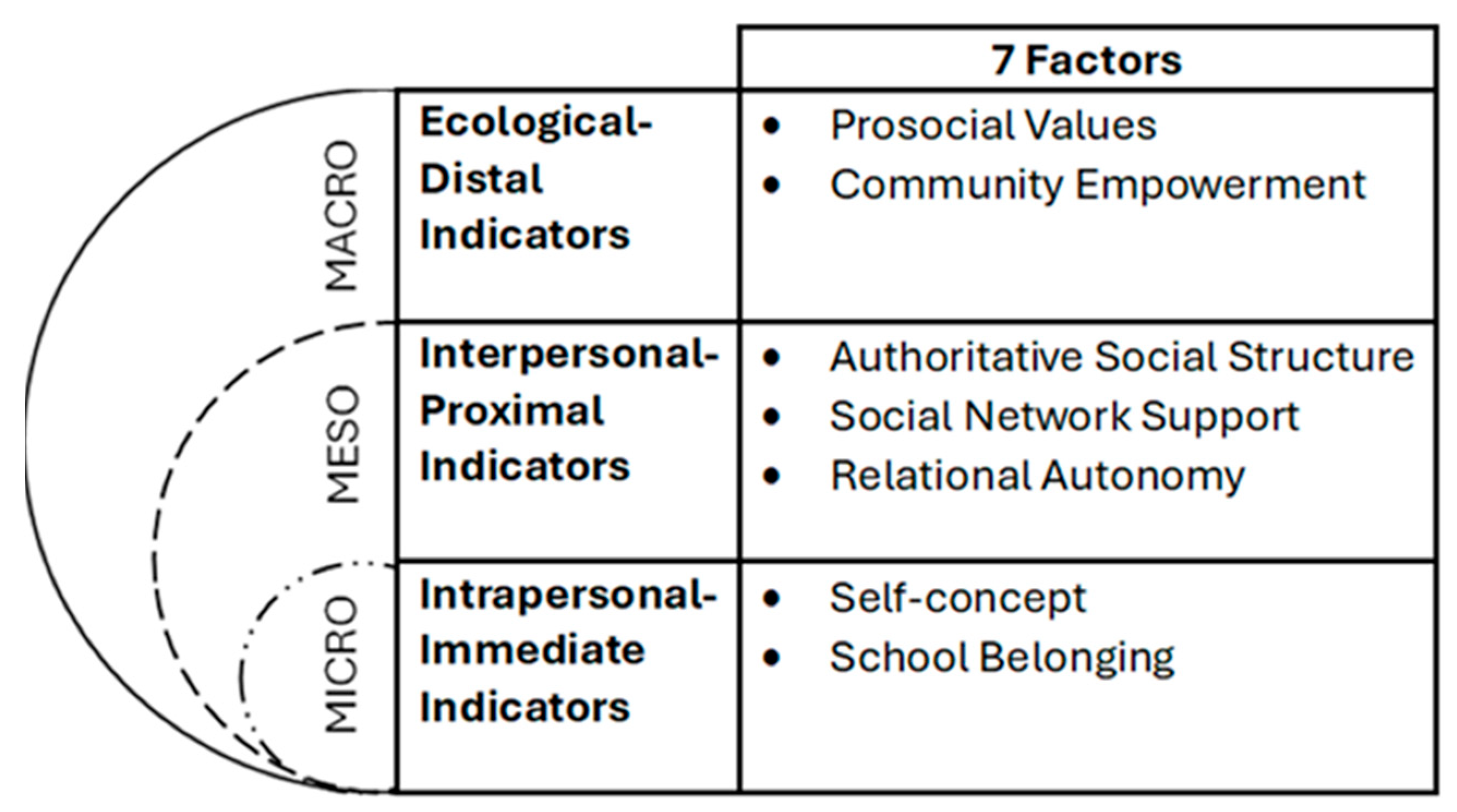

2. Theoretical Ground—Integrative Ecological Perspective

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Survey Procedure

3.2. Measure: Integrated PYD Framework

3.3. Data Analysis: Exploratory Ractor Analysis (EFA)

3.3.1. Item–Level Analysis

3.3.2. Decision to Retain Factors

4. Results: Seven-Factor Integrated PYD Framework

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PYD | Positive Youth Development |

| RDS | Relational Development Systems |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| NPO | Non-Profit Organisation |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| PAF | Principal Axis Factoring |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| IPYD | Integrated Positive Youth Development |

References

- Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, R. P., Huan, V. S., Chan, W. T., Cheong, S. A., & Leaw, J. N. (2015). The role of delinquency, proactive aggression, psychopathy and behavioral school engagement in reported youth gang membership. Journal of Adolescence, 41, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ani, F., Ramlan, N., Suhaimy, K. A. M., Jaes, L., Damin, Z. A., Halim, H., Bakar, S. K. S. A., & Ahmad, S. (2018, January). Applying empowerment approach in community development. In Proceedings of the international conference on social sciences (ICSS) (Vol. 1, No. 1). University of Muhammadiyah Jakarta. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M. E., Nott, B. D., & Meinhold, J. L. (2012). The positive youth development inventory short version (PYDI-S). Oregon State University. [Google Scholar]

- Baumsteiger, R. (2019). What the world needs now: An intervention for promoting prosocial behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 41(4), 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benish-Weisman, M., Daniel, E., Sneddon, J., & Lee, J. (2019). The relations between values and prosocial behavior among children: The moderating role of age. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P. L. (2006). All kids are our kids: What communities must do to raise caring and responsible children and adolescents. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Bin, L. (2021). Relational autonomy: A possible portrayal. In Tigor. Rivista di scienze della comunicazione e di argomentazione giuridica. EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 1). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Buenconsejo, J. U., & Datu, J. A. D. (2023). Toward an integrative paradigm of positive youth development: Implications for research, practice, and policy. Human Development, 66(6), 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, B. M., Robinson, K. M., Murray, E. D., & Lerner, R. M. (2020). Positive youth development: Theory and perspective. In The encyclopedia of child and adolescent development (pp. 2947–2958). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, R. F., Skinner, M. L., Alvarado, G., Kapungu, C., Reavley, N., Patton, G. C., Jessee, C., Plaut, D., Moss, C., Bennett, K., Sawyer, S. M., Sebany, M., Sexton, M., Olenik, C., & Petroni, S. (2019). Positive youth development programs in low-and middle-income countries: A conceptual framework and systematic review of efficacy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(1), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X., Wang, J., Li, X., Liu, W., Zhao, G., & Lin, D. (2022). Development and validation of the Chinese positive youth development scale. Applied Developmental Science, 26(1), 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiong, C. (2022). The texture and history of Singapore’s education meritocracy. In Education in Singapore: People-making and nation-building (pp. 151–168). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chiong, C., & Lim, L. (2022). Seeing families as policy actors: Exploring higher-order thinking reforms in Singapore through low-income families’ perspectives. Journal of Education Policy, 37(2), 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, P. L. Y., Ong, A. S. E., & Cheung, H. S. (2022). Where authoritarianism is not always bad: Parenting styles and romantic relationship quality among emerging adults in Singapore. Current Psychology, 41(7), 4657–4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C. M., Daffern, M., Thomas, S. D., Ang, Y., & Long, M. (2014). Criminal attitudes and psychopathic personality attributes of youth gang offenders in Singapore. Psychology, Crime & Law, 20(3), 284–301. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, V., & Seah, K. K. (2022). From meritocracy to parentocracy, and back. In Education in Singapore: People-making and nation-building (pp. 169–186). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Crone, E. A., & Fuligni, A. J. (2020). Self and others in adolescence. Annual Review of Psychology, 71(1), 447–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, K., & Dutton, H. (2020). The factors that influence positive youth development and wellbeing. In Key concepts, contemporary international debates and a review of the issues for Aotearoa New Zealand research, policy and practice. Ara Taiohi. [Google Scholar]

- Drmic, I. E., Aljunied, M., & Reaven, J. (2017). Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary treatment outcomes in a school-based CBT intervention program for adolescents with ASD and anxiety in Singapore. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 3909–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, C. J., & Wang, J. C. (2019). Aggressive video games are not a risk factor for future aggression in youth: A longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, D., Pivec, T., Dost-Gözkan, A., Uka, F., Gaspar de Matos, M., & Wiium, N. (2021). Global overview of youth development: Comparison of the 5 Cs and developmental assets across six countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 685316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freud, A. (1969). Adolescence as a developmental disturbance. In G. Caplan, & S. Lebovici (Eds.), Adolescence (pp. 5–10). Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gamper, M. (2022). Social network theories: An overview. Social Networks and Health Inequalities, 1(1), 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Geldhof, G. J., Bowers, E. P., Boyd, M. J., Mueller, M. K., Napolitano, C. M., Schmid, K. L., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Creation of short and very short measures of the five Cs of positive youth development. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, D. P., & Koh, A. (2023). The youth mental health crisis and the subjectification of wellbeing in Singapore schools. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 37, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, N., & Forrest, C. B. (2018). The emerging theoretical framework of life course health development. In Handbook of life course health development (pp. 19–43). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Halfon, N., Forrest, C. B., Lerner, R. M., Faustman, E. M., Tullis, E., & Son, J. (2018). Introduction to the Handbook of Life Course Health Development. In Handbook of life course health development (pp. 1–16). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and Its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education. D. Appleton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, M. T., Do, H. N., Dang, T. Q., Do, H. T., Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, L. H., Hoang, M. T., Do, H. N., Dang, T. Q., Do, H. T., Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, L. H., Nguyen, C. T., Doan, L. P., Vu, G. T., Ngo, T. V., Latkin, C. A., Ho, R. C. M., & Ho, C. S. (2021). Cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of Youth Quality of Life Instrument-Short Form (YQOL-SF) in a developing South-East Asian country. PLoS ONE, 16(6), e0253075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, T. J., Fitzgerald, S., Bossler, A. M., Chee, G., & Ng, E. (2016). Assessing the risk factors of cyber and mobile phone bullying victimization in a nationally representative sample of Singapore youth. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(5), 598–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhan, M., Güler, N., Teker, G. T., & Ergenekon, Ö. (2024). The effects of reverse items on psychometric properties and respondents’ scale scores according to different item reversal strategies. International Journal of Assessment Tools in Education, 11(1), 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R. (2020). The theory of empowerment: A critical analysis with the theory evaluation scale. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30(2), 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2021). Enhancing assessment literacy in professional counseling: A practical overview of factor analysis. Professional Counselor, 11(3), 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M. S., & Levine, P. B. (2020). Role models, mentors, and media influences. The Future of Children, 30(1), 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennan, D. (2015). Understanding the ethical requirement for parental consent when engaging youth in research. In Youth ’At the Margins’ (pp. 87–101). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & De Boer, H. (2020). The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Research Papers in Education, 35(6), 641–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J. A. (2018). Questionnaire design. In The Palgrave handbook of survey research (pp. 439–455). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Y. (2023). Relational approaches to personal autonomy. Philosophy Compass, 18(5), e12916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M. (2005, September). Promoting positive youth development: Theoretical and empirical bases. In White paper prepared for the workshop on the science of adolescent health and development, national research council/institute of medicine (pp. 1–90). National Academies of Science. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R. M. (2017). Commentary: Studying and testing the positive youth development model: A tale of two approaches. Child Development, 88(4), 1183–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Lewin-Bizan, S., Bowers, E. P., Boyd, M. J., Mueller, M. K., Schmid, K. L., & Napolitano, C. M. (2011). Positive youth development: Processes, programs, and problematics. Journal of Youth Development, 6(3), 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M., Tirrell, J. M., Dowling, E. M., Geldhof, G. J., Gestsdóttir, S., Lerner, J. V., King, P. E., Williams, K., Iraheta, G., & Sim, A. T. (2021). The end of the beginning: Evidence and absences studying positive youth development in a global context. In Individuals as producers of their own development (pp. 226–251). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Liau, A. K., Choo, H., Li, D., Gentile, D. A., Sim, T., & Khoo, A. (2015). Pathological video-gaming among youth: A prospective study examining dynamic protective factors. Addiction Research & Theory, 23(4), 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D. H., Chai, X. Y., Li, X., Liu, Y., & Weng, H. (2017). The conceptual framework of positive youth development in Chinese context: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Sciences), 6, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, R., Shildrick, T., & Furlong, A. (2020). ‘Cycles of disadvantage’ revisited: Young people, families and poverty across generations. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(1), 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, D., Lee, J. H., Chew, M. X. H., Sarfoji, M., & Prakash, T. (2021). Community-based rehabilitation’s effectiveness. In Reducing Singapore juvenile recidivism. Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, S. E., Wakia, J., Hembling, J., Bradford, B., Saran, I., Lombe, M., & Crea, T. M. (2024). Development of a child-informed measure of subjective well-being for research on residential care institutions and their alternatives in low-and middle-income countries. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 42, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M. M. (2014). Drug and alcohol addiction in Singapore: Issues and challenges in control and treatment strategies. International Aspects of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 2(3–4), 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S., Liu, J., Mahesh, M., Chua, B. Y., Shahwan, S., Lee, S. P., Vaingankar, J. A., Abdin, E., Fung, D. S. S., Chong, S. A., & Subramaniam, M. (2017). Stigma among Singaporean youth: A cross-sectional study on adolescent attitudes towards serious mental illness and social tolerance in a multiethnic population. BMJ Open, 7(10), e016432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Díaz, P. A., Nuno-Vasquez, S., Perazzo, M. F., & Wiium, N. (2022). Positive identity predicts psychological wellbeing in Chilean youth: A double-mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 999364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S., Hua, F., Zhou, Z., & Shek, D. T. (2022). Correction to: Trends of positive youth development publications (1995–2020): A scientometric review. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17(1), 447–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. B., & Leonard, K. F. (2024). Designing quality survey questions. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, J. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). Youth development programs: Risk, prevention and policy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 32(3), 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, E., Duell, N., & Steinberg, L. (2018). Brain development, social context, and justice policy. Wash. UJL & Pol’y, 57, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Search Institute. (n.d.). 40 developmental assets checklist. Available online: https://sites.rand.org/pubs/presentations/PT115/need-resource-assessment/story_content/external_files/40%20DA%20checklist%201st%20person.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Segrin, C., & Flora, J. (2018). Family communication. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D. T. L., Dou, D., Zhu, X., & Chai, W. (2019). Positive youth development: Current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 10, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D. T. L., Sin, A., & Lee, T. (2007). The Chinese positive youth development scale: A validation study. Research on Social Work Practice, 17, 380–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez Álvarez, J., Pedrosa, I., Lozano, L. M., García Cueto, E., Cuesta Izquierdo, M., & Muñiz Fernández, J. (2018). Using reversed items in Likert scales: A questionable practice. Psicothema, 2(30), 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukarieh, M., & Tannock, S. (2011). The positivity imperative: A critical look at the ‘new ’youth development movement. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(6), 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A. C., Rehfuss, M. C., Suarez, E. C., & Parks-Savage, A. (2014). Nonsuicidal self-injury in an adolescent population in Singapore. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(1), 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J. (2019). Equity and meritocracy in Singapore. In Equity in excellence: Experiences of East Asian high-performing education systems (pp. 111–125). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, S. S. (2019). Diversity and equity in Singapore education: Parental involvement in low-income families with migrant mothers. In Equity in excellence: Experiences of East Asian high-performing education systems (pp. 127–147). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, P., & Koh, D. (2024). Capitalising shadow education: A critical discourse analysis of private tuition websites in Singapore. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 56(4), 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. P. (2022). Authoritative parenting: The best style in children’s learning. American Journal of Education and Technology, 1(3), 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, W., Perales, F., Xiang, N., & Kubler, M. (2022). Differences in higher education access, participation and outcomes by socioeconomic background: A life course perspective. In Family dynamics over the life course: Foundations, turning points and outcomes (pp. 133–155). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Van Woudenberg, T. J., Rozendaal, E., & Buijzen, M. (2024). Parents’ perceptions of parental consent procedures for social science research in the school context. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 27(5), 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonneilich, N. (2022). Social relations, social capital, and social networks: A conceptual classification. In Social networks and health inequalities (p. 23). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Li, X., Bronk, K. C., & Lin, D. (2023). Factors that promote positive Chinese youth development: A qualitative study. Applied Developmental Science, 27(3), 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, K., & Fasbender, U. (2019). Self-concept. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, 1, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, M., Ye, Z., Lin, D., & Wang, W. (2022). Preliminary development of a multidimensional positive youth development scale for young rural and urban adolescents in China. PLoS ONE, 17(7), e0270974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiium, N., & Dimitrova, R. (2019). Positive youth development across cultures: Introduction to the special issue. Child Youth Care Forum, 48, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. L., & Deutsch, N. L. (2016). Beyond between-group differences: Considering race, ethnicity, and culture in research on positive youth development programs. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. W. C., Kwok, K. W., & Chow, S. L. (2022, October). Validation of positive youth development scale and implications for adolescent in Hong Kong community. In Child & Youth Care Forum (Vol. 51, No. 5, pp. 901–919). Springer US. [Google Scholar]

- Zaremohzzabieh, Z., Krauss, S., & Nouri, K. M. (2024). Factor Structure validation and measurement invariance testing of the five c’s model of positive youth development among emerging adults in Malaysia. Emerging Adulthood, 12(1), 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Mean | Std Dev | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 3.239 | 1.029 | −0.023 | −0.379 |

| A2 | 3.280 | 1.003 | −0.116 | −0.448 |

| A3 | 3.478 | 1.049 | −0.252 | −0.561 |

| A4 | 2.820 | 1.042 | 0.132 | −0.458 |

| A5 | 3.231 | 0.993 | −0.005 | −0.453 |

| A6 | 3.610 | 1.089 | −0.340 | −0.688 |

| B1 | 3.187 | 1.011 | 0.112 | −0.509 |

| B2 | 3.156 | 0.984 | 0.074 | −0.465 |

| B3 | 3.488 | 1.078 | −0.266 | −0.604 |

| C1 | 3.712 | 0.982 | −0.340 | −0.536 |

| C2 | 3.078 | 1.002 | 0.106 | −0.486 |

| C3 | 3.852 | 0.934 | −0.472 | −0.414 |

| C4 | 3.293 | 1.049 | −0.012 | −0.662 |

| C5 | 3.846 | 1.080 | −0.693 | −0.321 |

| C6 | 3.881 | 0.999 | −0.597 | −0.196 |

| D1 | 2.906 | 1.189 | 0.136 | −0.811 |

| D2 | 3.423 | 1.080 | −0.185 | −0.674 |

| D3 | 3.207 | 1.098 | −0.150 | −0.569 |

| D4 | 3.649 | 1.059 | −0.444 | −0.442 |

| D5 | 3.593 | 1.004 | −0.302 | −0.481 |

| D6 | 3.574 | 1.040 | −0.350 | −0.412 |

| E1 | 3.712 | 0.982 | −0.371 | −0.466 |

| E2 | 3.919 | 0.908 | −0.455 | −0.452 |

| E3 | 3.820 | 0.988 | −0.446 | −0.486 |

| E4 | 4.070 | 0.910 | −0.660 | −0.350 |

| F1 | 3.597 | 1.026 | −0.403 | −0.260 |

| F2 | 2.244 | 1.154 | 0.701 | −0.330 |

| F3 | 3.089 | 1.065 | 0.089 | −0.609 |

| F4 | 2.992 | 1.122 | 0.009 | −0.706 |

| F5 | 2.980 | 1.105 | 0.046 | −0.558 |

| G1 | 3.650 | 0.982 | −0.373 | −0.392 |

| G2 | 3.748 | 0.975 | −0.429 | −0.425 |

| G3 | 3.714 | 0.985 | −0.315 | −0.655 |

| G4 | 3.844 | 0.979 | −0.455 | −0.623 |

| Analysis | No of Items with Loadings Across 2 Factors | No of Items with Loadings Across 3 Factors | No of Items with Loadings Above 0.32 | Interpretability to the PYD Constructs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-factor | 6 | 0 | 33 | Distinct constructs are grouped in 2 of the factors |

| 6-factor | 6 | 0 | 33 | Better differentiation of constructs but 2 factors have distinct constructs grouped under them |

| 7-factor | 4 | 0 | 33 | Clearer distinction of constructs |

| 8-factor | 2 | 1 | 34 | One item has excessive cross loading on 3 factors and the removal of this item will cause the factor to have only 2 items |

| Factor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| A2 | 0.856 | ||||||

| A4 | 0.747 | ||||||

| A5 | 0.683 | ||||||

| A1 | 0.675 | ||||||

| A3 | 0.669 | ||||||

| A6 | 0.626 | ||||||

| B2 | 0.403 | ||||||

| D2 | 0.854 | ||||||

| D1 | 0.805 | ||||||

| D3 | 0.770 | ||||||

| D4 | 0.738 | ||||||

| D5 | 0.517 | ||||||

| G2 | 0.845 | ||||||

| G1 | 0.801 | ||||||

| G4 | 0.791 | ||||||

| G3 | 0.444 | ||||||

| F4 | 0.869 | ||||||

| F5 | 0.734 | ||||||

| F3 | 0.713 | ||||||

| E4 | 0.820 | ||||||

| E2 | 0.714 | ||||||

| E3 | 0.648 | ||||||

| D6 | 0.918 | ||||||

| F1 | 0.678 | ||||||

| B3 | 0.468 | ||||||

| C3 | 0.610 | ||||||

| C4 | 0.563 | ||||||

| C1 | 0.562 | ||||||

| C6 | 0.459 | ||||||

| C5 | 0.390 | ||||||

| C2 | 0.332 | ||||||

| No. | Indicators | Factor | Cronbach’s Alpha | McDonald’s Omega | No. of Items | Range of Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Intrapersonal-Immediate | Self-concept | 0.870 | 0.869 | 7 | 0.403 to 0.856 |

| 2 | Interpersonal-Proximal | Social Network Support | 0.892 | 0.892 | 5 | 0.517 to 0.854 |

| 3 | Ecological-Distal | Prosocial Values | 0.858 | 0.859 | 4 | 0.444 to 0.845 |

| 4 | Ecological-Distal | Community Empowerment | 0.864 | 0.865 | 3 | 0.713 to 0.869 |

| 5 | Interpersonal-Proximal | Authoritative Social Structure | 0.881 | 0.882 | 3 | 0.648 to 0.820 |

| 6 | Intrapersonal-Immediate | School Belonging | 0.781 | 0.785 | 3 | 0.468 to 0.918 |

| 7 | Interpersonal-Proximal | Relational Autonomy | 0.821 | 0.821 | 6 | 0.332 to 0.610 |

| Factors | Literature |

|---|---|

| 1. Prosocial Values: Prosocial values provide guiding principles or motivational goals leading to voluntary behaviours (e.g., helping, sharing) that support the social fabric or advance the welfare of others. In this way, such behaviour contributes to the world beyond oneself, and a difference is made in the lives of others. Behaving according to prosocial values is inherently rewarding and found to reflexively benefit the prosocial person in terms of physical and psychological well-being. Those who consider such values as central to their self-identity are more likely to exhibit prosocial behaviour across situations. | Baumsteiger (2019); Benish-Weisman et al. (2019) |

| 2. Self-Concept: Self-concept contains one’s self-related beliefs and self-evaluations, mediating the connection between social context and individual behaviour. It persists but is also malleable and fluid across time, and it affects and is affected by life experiences and social expectations in a particular environment. Adolescence is an important transition phase for self-concept development, which affects the youth’s capacity to commit to goals for the future. A stable and clear self-concept is positively associated with prosocial values and predicts better social relations. | Crone and Fuligni (2020); Wehrle and Fasbender (2019) |

| 3. School Belonging: In terms of psychological functioning, school belonging is understood as the extent of personal acceptance, respect, inclusion, and support felt by the child in the school context. It operates through school-based relationships and experiences, student–teacher relationships, and the child’s general feelings about the school, with factors such as academic motivation, teacher support, and environmental safety affecting the sense of school belonging for the student. School belonging contributes to better academic achievement and behavioural, social–emotional, and cognitive outcomes for the student. | Allen et al. (2018); Korpershoek et al. (2020) |

| 4. Community Empowerment: Community empowerment is a bottom–up process of highlighting community members as key in the development of the community through believing in each of their potentials and discovering, enhancing, and expanding their human ability. Empowerment becomes a transformative tool, enabling a sense of agency in each community member to act in response to any domain pressure (e.g., socioeconomic, political, religious) that impacts lives at any level of society—from the individual to a collective—hence encouraging community participation. | Ani et al. (2018); Joseph (2020) |

| 5. Authoritative Social Structure: Although culture and tradition affect parenting style, the demand of the present world necessitates authoritative parenting, evaluated as the child development approach able to provide fair and consistent discipline while expressing warmth and nurturing. And while parents are a child/ youth’s significant role models, non-parental role models or mentors in the environment (even through media) also affect the individual’s learning and developmental outcomes. This presence of caring, authoritative adults able to provide guidance and structure contributes to his or her healthy development towards becoming a “complete human being” with socially valued self-esteem, social skills, discipline, and democratic values (e.g., cooperation, collective decision-making for rightful purposes). | Kearney and Levine (2020); Scott et al. (2018); Tiwari (2022); |

| 6. Social Network Support: People are embedded in relationships within networks through which they negotiate, construct, are given recognition of, and can stabilise their social identities. Stronger relationships serve as a more likely source of social support—inclusive of cultural and social capital (i.e., access to resources) and taking place on emotional, instrumental, and informational levels. Certainly, resources can be obtained through contacts of lower frequencies and depth, established through different social groups and thereby increasing probability of resource access. Still, the family (and tribe), as the social form that the individual is born into, is considered the primary social circle, one depended on since birth, and long after, to meet a range of needs. Also, task-orientated interactions (including verbal and nonverbal communications) would facilitate feelings of family identity, interdependence, and commitment among its members. | Gamper (2022); Segrin and Flora (2018); Vonneilich (2022) |

| 7. Relational Autonomy: Autonomous agency does not imply escaping from social influences; rather, one is able to fashion a certain response to it. The individual self is shaped by social relationships and social determinants (e.g., gender, race, and class). As such, personal autonomy can only be developed within a society, where the ways complex social factors contribute to or constrain individual autonomy can be explored. People can be autonomous to varying degrees, exercising differing multidimensional combinations of self-determination, self-governance, and self-authorisation. These dimensions are characterised by having the freedom to decide and enact choices affecting one’s life and personal identity; possession of skills, competencies, and internal authenticity to make and enact such choices; and a willingness to be accountable and self-evaluative of the choices made. | Bin (2021); Lee (2023) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chung, Y.J.; Lim, Q.P.; Goh, C.P.; Chong, S.; Hor, K.K.L. Positive Youth Development Revisited: A Contextual–Theoretical Approach for Disadvantaged Youth in Singapore. Youth 2025, 5, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040109

Chung YJ, Lim QP, Goh CP, Chong S, Hor KKL. Positive Youth Development Revisited: A Contextual–Theoretical Approach for Disadvantaged Youth in Singapore. Youth. 2025; 5(4):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040109

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, You Jin, Qiu Ping Lim, Chwee Peng Goh, Sylvia Chong, and Karen Kar Lin Hor. 2025. "Positive Youth Development Revisited: A Contextual–Theoretical Approach for Disadvantaged Youth in Singapore" Youth 5, no. 4: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040109

APA StyleChung, Y. J., Lim, Q. P., Goh, C. P., Chong, S., & Hor, K. K. L. (2025). Positive Youth Development Revisited: A Contextual–Theoretical Approach for Disadvantaged Youth in Singapore. Youth, 5(4), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040109