The Need for Social Developmental Research on Internal and External Motivation to Respond Without Prejudice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. IMRWP and EMRWP Research Among Adults

3. Theories of Prejudice in Childhood

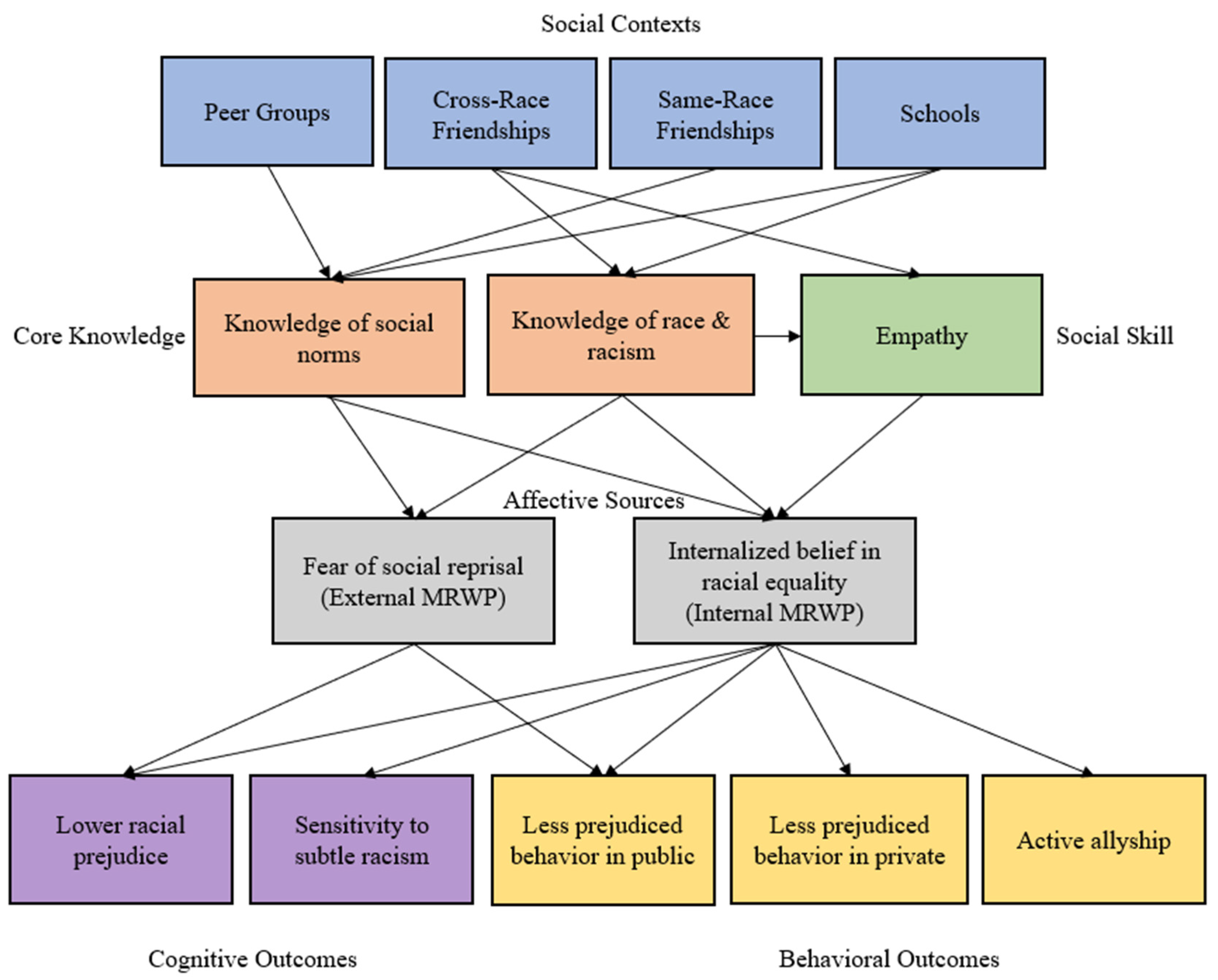

4. IMRWP and EMRWP Development in Children

5. A Guide for Future Developmental Research on IMRWP and EMRWP

6. Peer Group Influences on IMRWP and EMRWP

7. Friendships as Sources of IMRWP

7.1. Cross-Race Friendships

7.2. Same-Ethnicity/Race Friendships

8. School Factors in IMRWP and EMRWP Development

8.1. Structural Factors

8.2. Administrative Factors

8.3. Teacher Factors

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboud, F. E., & Fenwick, V. (1999). Exploring and evaluating school-based interventions to reduce prejudice. Journal of Social Issues, 55(4), 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, F. E., & Steele, J. R. (2017). Theoretical perspectives on the development of implicit and explicit prejudice. In A. Rutland, D. Nesdale, & C. S. Brown (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of group processes in children and adolescents (pp. 165–184). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, D., Rutland, A., Cameron, L., & Ferrell, J. (2007). Older but wilier. Developmental Psychology, 43(1), 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Apfelbaum, E. P., Pauker, K., Sommers, S. R., & Ambady, N. (2010). In blind pursuit of racial equality? Psychological Science, 21(11), 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, S. C., Cameron, L., Turner, R. N., Morais, C., Carby, A., Ndhlovu, M., & Leney, A. (2020). Cross-ethnic friendship self-efficacy: A new predictor of cross-ethnic friendships among children. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 23(7), 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A. (2023, April 13). South Arkansas school resegregation likely as AG taps courts to erase integration measures. Arkansas Times.

- Bamberg, K., & Verkuyten, M. (2021). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice: A person-centered approach. The Journal of Social Psychology, 162(4), 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler, R. S., & Liben, L. S. (2007). Developmental intergroup theory: Explaining and reducing children’s social stereotyping and prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(3), 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler, R. S., & Wright, Y. F. (2014). Reading, writing, arithmetic, and racism? risks and benefits to teaching children about intergroup biases. Child Development Perspectives, 8(1), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. (1995). Prejudice: Its social psychology. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R., Eller, A., Leeds, S., & Stace, K. (2007). Intergroup contact and intergroup attitudes: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(4), 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, W. M. (2001). Friendship and the worlds of childhood. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 91, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkholder, A. R., D’Esterre, A. P., & Killen, M. (2019). Intergroup relationships, context, and prejudice in childhood. In H. E. Fitzgerald, D. J. Johnson, D. B. Qin, F. A. Villarruel, & J. Norder (Eds.), Handbook of children and prejudice (pp. 115–130). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, D. A., & Plant, E. A. (2009). Prejudice control and interracial relations: The role of motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality, 77(5), 1311–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerini, A., & Schulz, P. J. (2018). Social desirability bias in child-report social well-being: Evaluation of the children’s social desirability short scale using item response theory and examination of its impact on self-report family and peer relationships. Child Indicators Research, 11(4), 1159–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, L., & Turner, R. N. (2017). Intergroup contact among children. In S. Stathi, & L. Vezzali (Eds.), Intergroup contact theory: Recent developments and future directions (pp. 151–168). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan, R. W. (2018). Divergent trends in neighborhood and school segregation in the age of school choice. Peabody Journal of Education, 93(4), 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, N. R. (1996). The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Development, 67, 2317–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K., Tropp, L. R., Aron, A., Pettigrew, T. F., & Wright, S. C. (2011). Cross-group friendships and intergroup attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(4), 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51(3), 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, R. A., Hoffman, K. M., Lillard, A. S., & Trawalter, S. (2014). Children’s racial bias in perceptions of others’ pain. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 32(2), 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A., & Lockwood, S. (2023). Addressing hate crime in the 21st century: Trends, threats, and opportunities for intervention. Annual Review of Criminology, 6(1), 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzRoy, S., & Rutland, A. (2010). Learning to control ethnic intergroup bias in childhood. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, R., Rebelo, M., Monteiro, M. B., & Gaertner, S. L. (2013). Translating recategorization strategies into an antibias educational intervention. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(1), 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelbaker, T., Brown, C. S., Nenadal, L., & Mistry, R. S. (2022). Fostering anti-racism in white children and youth: Development within contexts. The American Psychologist, 77(4), 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D., Rodriguez, J., Smith, E. P., Johnson, D. J., Stevenson, H. C., & Spicer, P. (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. M., Alo, J., Krieger, K., & O’Leary, L. M. (2016). Emergence of internal and external motivations to respond without prejudice in white children. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(2), 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. M., Bigler, R. S., & Levy, S. R. (2007). Consequences of learning about historical racism among European American and African American children. Child Development, 78(6), 1689–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husnu, S., Mertan, B., & Cicek, O. (2018). Reducing Turkish Cypriot children’s prejudice toward Greek Cypriots: Vicarious and extended intergroup contact through storytelling. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(1), 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jargon, M., & Thijs, J. (2021). Antiprejudice norms and ethnic attitudes in preadolescents: A matter of stimulating the “right reasons”. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(3), 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. J., & Aboud, F. E. (2017). Evaluation of an intervention using cross-race friend storybooks to reduce prejudice among majority race young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 40, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, M., Crystal, D. S., & Ruck, M. (2007). The social developmental benefits of intergroup contact among children and adolescents. In E. Frankenburg, & G. Orfield (Eds.), Lessons in integration: Realizing the promise of racial diversity in American schools (pp. 57–73). University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Killen, M., Luken Raz, K., & Graham, S. (2022). Reducing prejudice through promoting cross-group friendships. Review of General Psychology, 26(3), 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, M., & Smetana, J. G. (2005). Social–Cognitive domain theory: Consistencies and variations in children’s moral and social judgments. In M. Killen, & J. G. Smetana (Eds.), Handbook of moral development. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Killen, M., & Stangor, C. (2001). Children’s social reasoning about inclusion and exclusion in gender and race peer group contexts. Child Development, 72(1), 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntsman, J. W., Plant, E. A., Zielaskowski, K., & LaCosse, J. (2013). Feeling in with the outgroup: Outgroup acceptance and the internalization of the motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(3), 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCosse, J., & Plant, E. A. (2020). Internal motivation to respond without prejudice fosters respectful responses in interracial interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(5), 1037–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, L., Gutsell, J. N., & Inzlicht, M. (2011). Ironic effects of antiprejudice messages: How motivational interventions can reduce (but also increase) prejudice. Psychological Science, 22(12), 1472–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, F., Molnar, A., Johnson, R., Patterson, A., Ward, L., & Kumashiro, K. (2021). Understanding the attacks on critical race theory. National Education Policy Center. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, M. B., de França, D. X., & Rodrigues, R. (2009). The development of intergroup bias in childhood: How social norms can shape children’s racial behaviours. International Journal of Psychology, 44(1), 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Security Council. (2021). Fact sheet: National strategy for countering domestic terrorism. Executive Office of the President, National Security Council. [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale, D. (2004). Social identity processes and children’s ethnic prejudice. In F. Sani, & M. Bennett (Eds.), The development of the social self. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale, D. (2011). Social groups and children’s intergroup prejudice: Just how influential are social group norms? Annals of Psychology, 27(3), 600–610. [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale, D. (2012). The development of children’s ethnic prejudice: The critical influence of social identity, social group norms, and social acumen. In D. W. Russell, & C. A. Russell (Eds.), The psychology of prejudice (pp. 51–76). Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale, D., & Dalton, D. (2011). Children’s social groups and intergroup prejudice: Assessing the influence and inhibition of social group norms. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 29(4), 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, H. A., Awad, G. H., Brooks, J. E., Flores, M. P., & Bluemel, J. (2013). Color-blind racial ideology. The American Psychologist, 68(6), 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, A. W., Friehs, M., Bracegirdle, C., Zúñiga, C., Watt, S. E., & Barlow, F. K. (2021). Technological and analytical advancements in intergroup contact research. Journal of Social Issues, 77(1), 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Over, H., & McCall, C. (2018). Becoming us and them: Social learning and intergroup bias. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(4), e12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(6), 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 811–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, M., Rogers, J., Kwako, A., Matschiner, A., Kendall, R., Bingener, C., Reece, E., Kennedy, B., & Howard, J. (2022). The conflict campaign: Exploring local experiences of the campaign to ban “critical race theory” in public K–12 education in the U.S., 2020–2021. UCLA’s Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access. [Google Scholar]

- Priest, N., Walton, J., White, F., Kowal, E., Fox, B., & Paradies, Y. (2016). ‘You are not born being racist, are you?’ discussing racism with primary aged-children. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 19(4), 808–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M. K., Heyman, G. D., Quinn, P. C., Fu, G., & Lee, K. (2019). Differential developmental courses of implicit and explicit biases for different other-race classes. Developmental Psychology, 55(7), 1440–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, T., & Beelmann, A. (2011). Development of ethnic, racial, and national prejudice in childhood and adolescence: A multinational meta-analysis of age differences. Child Development, 82(6), 1715–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Drake, D., Saleem, M., Schaefer, D. R., Medina, M., & Jagers, R. (2019). Intergroup contact attitudes across peer networks in school: Selection, influence, and implications for cross-group friendships. Child Development, 90(6), 1898–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M. T., Green, E. R., Dunham, Y., Bruneau, E., & Rhodes, M. (2022). Beliefs about social norms and racial inequalities predict variation in the early development of racial bias. Developmental Science, 25(2), e13170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Bowker, J. C. (2015). Children in peer groups. In Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (Vol. 4, pp. 175–222). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Rutland, A., Cameron, L., Milne, A., & McGeorge, P. (2005). Social norms and self-presentation: Children’s implicit and explicit intergroup attitudes. Child Development, 76(2), 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, A., & Killen, M. (2015). A developmental science approach to reducing prejudice and social exclusion: Intergroup processes, social-cognitive development, and moral reasoning. Social Issues and Policy Review, 9(1), 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijs, J., Miklikowska, M., & Bosman, R. (2023). Motivations to respond without prejudice and ethnic outgroup attitudes in late childhood: Change and stability during a single school year. Developmental Psychology, 59(9), 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropp, L. R., White, F., Rucinski, C. L., & Tredoux, C. (2022). Intergroup contact and prejudice reduction: Prospects and challenges in changing youth attitudes. Review of General Psychology, 26(3), 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. C., Brown, R. J., & Tajfel, H. (1979). Social comparison and group interest in ingroup favouritism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 9(2), 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R. N., & Cameron, L. (2016). Confidence in contact: A new perspective on promoting cross-group friendship among children and adolescents. Social Issues and Policy Review, 10(1), 212–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Research Questions |

|---|---|

| General IMRWP/EMRWP development |

|

| Peer factors in IMRWP/EMRWP |

|

| Friendships and IMRWP/EMRWP |

|

| School-level factors in IMRWP/EMRWP |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pitcher, K.J.; Smith, R.L. The Need for Social Developmental Research on Internal and External Motivation to Respond Without Prejudice. Youth 2025, 5, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040103

Pitcher KJ, Smith RL. The Need for Social Developmental Research on Internal and External Motivation to Respond Without Prejudice. Youth. 2025; 5(4):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040103

Chicago/Turabian StylePitcher, Katelyn J., and Rhiannon L. Smith. 2025. "The Need for Social Developmental Research on Internal and External Motivation to Respond Without Prejudice" Youth 5, no. 4: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040103

APA StylePitcher, K. J., & Smith, R. L. (2025). The Need for Social Developmental Research on Internal and External Motivation to Respond Without Prejudice. Youth, 5(4), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040103