A Scoping Review of Youth Development Measures to Mitigate Drug and Alcohol Abuse Among Young People in the SADC Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- What youth development intervention programmes are implemented by seven governments and non-governmental organisations to mitigate drug and alcohol abuse among youth in the SADC region?

- (ii)

- What effective youth development or youth work models can be used to address drug and alcohol abuse among youths in the SADC region?

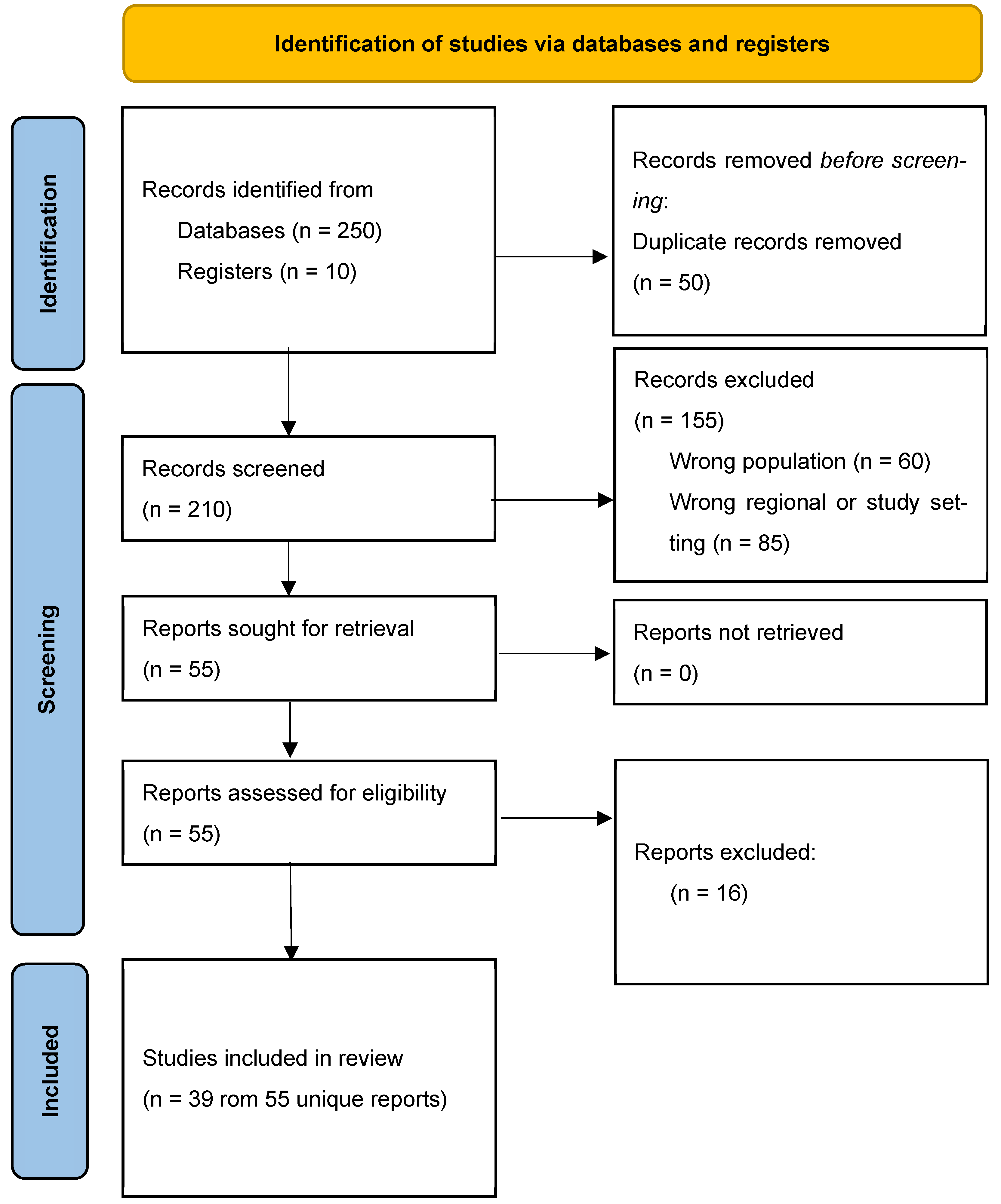

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- (i)

- Study designs: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research; policy analyses; programme evaluations.

- (ii)

- Participants: young people aged 14–35 years in any of the seven selected SADC countries; interventions involving youth workers, teachers, social workers, health practitioners, or NGOs.

- (iii)

- Publication type: peer-reviewed journal articles, government reports, organisational policy documents, and grey literature.

- (iv)

- Language: English.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- (i)

- Studies not focused on youth-specific substance abuse interventions.

- (ii)

- Studies conducted outside the seven target countries.

- (iii)

- Opinion pieces or commentaries without intervention description.

- (iv)

- Studies in other languages than English

3. Results and Discussion

An Overview of Youth Development Measures in the SADC Region

4. Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, K., & Hubbard, D. (2009). Alcohol and youths: Suggestions for law reform. Legal Assistance Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Chauke, T. A. (2023). Responsive measures for youth development to prevent delinquent behaviour among youths not in education, employment or training. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 35(2), 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikwanah, E. (2019). Zimbabwe church trains youth leaders to avoid drugs. UM News. Available online: https://www.umnews.org (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Cupido, X. (2017). An exploration of school-based substance-abuse prevention programmes in the Cape metropolitan region [Unpublished master’s thesis, University of the Western Cape]. [Google Scholar]

- Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Arshad, A., Finkelstein, Y., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Interventions for adolescent substance abuse: An overview of systematic reviews. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4S), 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Social Development. (2013). Substance use, misuse and abuse amongst the youth in Limpopo Province. Department of Social Development. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Social Development. (2019). National drug master plan: 2019 to 2024 South Africa free of substance abuse. Department of Social Development. [Google Scholar]

- Diraditsile, K., & Rasesigo, K. (2018). Substance abuse and mental health effects among the youth in Botswana: Implications for Social Research. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science, 24(2), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzinamarira, T. R., Mutevere, M., Nyoka, S., Moyo, E., Mkwapatira, M., Murewanhema, G., & Dzinamarira, T. (2023). Illicit substance use among adolescents and youths in Zimbabwe: A stakeholder’s perspective on the enabling factors and potential strategies to address this scourge. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 10(8), 2913–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpenyong, S. N. (2012). Drug abuse in Nigerian schools: A study of selected secondary institutions in Bayelsa State, South-South, Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific Research in Education, 5(3), 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, B. J., & Grim, M. E. (2019). Belief, behavior, and belonging: How faith is indispensable in preventing and recovering from substance abuse. Journal of Religion and Health, 58(5), 1713–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Y., Zilanawala, A., Booker, C., & Sacker, A. (2019). Social media use and adolescent mental health: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. EClinicalMedicine, 6, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H. G. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry, 2012, 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumuterera, C. (2019, November 6). Church continues to support cyclone Idai victims. UM News. Available online: www.umnews.org (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Letamo, G., Bowelo, M., & Majelantle, R. (2016). Prevalence of substance use, and correlates of multiple substance use among school going adolescents in Botswana. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies, 15(2), 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Macheka, T., & Masuku, S. (2019). Youth participation structures in Zimbabwe: A lens into the experiences of rural youth within WADCOs and VIDCOs. Centre for Social Science Research, UCT. [Google Scholar]

- Machethe, P., Obioha, E., & Mofokeng, J. (2022). Community-based initiatives in preventing and combatting drug abuse in a South African township. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 11(1), 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaya, E. (2017). An assessment of the impact of e-government on service delivery in Zimbabwe’s public sector. The case of Home Affairs: Department of the Zimbabwe Republic Police from period 2005–2015. Afribary. [Google Scholar]

- Mahiya, I. T. (2016). Urban youth unemployment in the context of a dollarised economy in Zimbabwe. Commonwealth Youth and Development, 14(1), 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makande, N. A. (2017). The effectiveness of the Zimbabwe Republic Police Criminal Investigation Department in curbing drug abuse among youths in Zimbabwe: A case of Mbare [Unpublished master’s thesis, Midlands States University]. [Google Scholar]

- Makwanise, N. (2023). The challenges of fighting drug abuse among the youth in Zimbabwe. GNOSI: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Human Theory and Praxis, 6(2), 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Maraire, T., Chethiyar, S. D. M., & Jasni, M. A. B. (2020). A general review of Zimbabwe’s response to drug and substance abuse among the youth. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraire, T., Ismail, S. B., & Jasni, M. A. B. (2022). A Christian based drug abuse intervention among Zimbabwean youths: An empirical investigation. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(6), 10099–10113. [Google Scholar]

- Masihleho, M. J., & Khalanyane, T. (2009). The impact of Thaba-Bosiu Centre alternative livelihoods programme on alcohol problems: A case study of Ha Mothae. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies, 8(2), 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Masiye, I., & Ndhlovu, D. (2015). Drug and alcohol abuse prevention education in Zambia’s secondary schools: Literature survey. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, 2(10), 513–517. Available online: https://www.allsubjectjournal.com/assets/archives/2015/vol2issue10/2-10-69.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2024).[Green Version]

- Matunhu, J., & Matunhu, V. (2016). Drugs and drug control in Zimbabwe. In A. Kalunta-Crumpton (Ed.), Pan-African issues in drugs and drug control (pp. 155–178). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matutu, V., & Mususa, D. (2019). Drug and alcohol abuse among young people in zimbabwe: A crisis of morality or public health problem. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3489954 (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Mertens, D. M., & Wilson, A. T. (2012). Program evaluation theory and practice: Acomprehensive guide. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mhlongo, T. (2005). Drug abuse in adolescents in Swaziland [Unpublished dissertation, University of South Africa]. [Google Scholar]

- Midford, R., Lenton, S., & Hancock, L. (2000). A critical review and analysis: Cannabis education in schools. NSW Department of Cutin University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Mofokeng, M. (2013, October 7–9). Effects on the family: Destruction behind quenching the thirst [Paper presentation]. Global Alcohol Policy Conference 2013 (GAPC 2013), Seoul, Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Mphande, F., Kalimaposo, K., Mubita, K., Milupi, I., Mundende, K., Phiri, C., & Daka, H. (2023). Voices of teachers and pupils on school-based alcohol abuse preventive strategies in selected schools of Lusaka, Zambia. Research Studies, 3(5), 932–940. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Mudavanhu, N., & Schenck, R. (2014). Substance abuse amongst the youth in Grabouw Wester Cape: Voices from the Community. Social Work, 50(3), 370–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukwenha, S., Murewanhema, G., Madziva, R., Dzinamarira, T., Herrera, H., & Musuka, G. (2022). Increased illicit substance use among Zimbabwean adolescents and youths during the COVID-19 era: An impending public health disaster. Addiction, 117(4), 1177–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaudzi, H. (2018). Factors contributing to substance abuse among youth in Atteridgeville, Tshwane Metropolitan, South Africa [Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Venda]. [Google Scholar]

- Muthelo, L., Mbombi, M. O., Mphekgwana, P., Mabila, L. N., Dhau, I., Tlouyamma, J., Nemuramba, R., Mashaba, R. G., Mothapo, K., Ntimana, C. B., & Maimela, E. (2023). Exploring roles of stakeholders in combating substance abuse in the DIMAMO Surveillance Site, South Africa. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17, 11782218221147498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, P., Mangoma-Chaurura, J., Khan, G., Canham, B., & Malope-Rwodzi, N. (2016). Using sport as an intervention for substance abuse reduction among adolescents and young adults in three selected communities in South Africa: An exploratory study. Human Sciences Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- National Youth Policy. (2021). A decade to accelerate positive youth development. The Presidency of Republic of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Ndawonde, S. (2020). Examining substance abuse prevention strategies to combat school violence in Inanda, KZN, South Africa [Unpublished masters’ thesis, University of Kwazulu-Natal]. [Google Scholar]

- Netope, R. N., Nghitanwa, E. M., & Endjala, T. (2023). Investigation of the determinants of alcohol use among women in Oshikoto region, Namibia. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 14(3), 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngcobo, P. (2018). An examination of substance abuse prevention programmes and their impact on minors who are prone to substance abuse in South Africa [Unpublished master’s thesis, University of KwaZulu Natal]. [Google Scholar]

- Nhapi, T. (2019). Drug addiction among youths in Zimbabwe: Social work perspective. In Y. Ndasauka, & G. M. Kayange (Eds.), Addiction in South and East Africa (pp. 241–259). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhapi, T., & Mathende, T. (2016). Drug abuse: An out of school adolescent’s survival mechanism in the context of a turbulent economic landscape–some Zimbabwean perspectives. Acta Criminologica, 29(3), 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Nyashanu, T., & Visser, M. (2022). Treatment barriers among young adults living with a substance use disorder in Tshwane, South Africa. Substance Abuse and Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyimbili, F., Mainza, R., Mumba, L., & Kutunansa, B. (2019). Teacher and parental involvement in providing comprehensive sexuality education in selected primary schools of Kalomo district of Zambia. Journal of Adult Education, 1(2), 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, M. J. (2016). Cognitive behavioural therapy for Christian clients with depression: A practical tool-based primer. Templeton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pitso, J. M. N., & Obot, I. S. (2011). Botswana alcohol policy and the presidential levy controversy. Addiction, 106(5), 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pufall, E. L., Eaton, J. W., Robertson, L., Mushati, P., Nyamukapa, C., & Gregson, S. (2017). Education, substance use, and HIV risk among orphaned adolescents in Eastern Zimbabwe. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 12(4), 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranotsi, A., Makatjane, T., & Aiyuk, S. (2012). The extent of drug abuse in Lesotho: The case of Mapoteng community. Lesotho Medical Association Journal, 10(1), 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Riva, K., Allen-Taylor, L., Schupmann, W. D., Mphele, S., Moshashane, N., & Lowenthal, E. D. (2018). Prevalence and predictors of alcohol and drug use among secondary school students in Botswana: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, O. A., Weir, C., & Aceves-Martins, M. (2021). Substance use prevention interventions for children and young people in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 94, 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setlalentoa, M., Ryke, E., & Strydom, H. (2015). Intervention strategies used to address alcohol abuse in the North-West province, South Africa. Social Work, 51(1), 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibalika, M., & Chileshe, B. (2022). Perceptions of stakeholders on the causes of drug abuse among primary school learners in Shibuyunji District, Zambia. Multidisciplinary Journal of Language and Social Sciences Education, 5(1), 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Strijdom, J. L. (1992). A drug policy and strategy for Namibia [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Bophuthatswana]. [Google Scholar]

- Tomokawa, S., Miyake, K., Akiyama, T., Makino, Y., Nishio, A., Kobayashi, J., Jimba, M., Ayi, I., Njenga, S. M., & Asakura, T. (2020). Effective school-based preventive interventions for alcohol use in Africa: A systematic review. African Health Sciences, 20(3), 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triolo, M., Bhattacharya, D., & Hood, D. A. (2022). Denervation induces mitochondrial decline and exacerbates lysosome dysfunction in middle-aged mice. Aging, 14(22), 8758–8773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC]. (2013). Making the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region safer from crime and drugs regional programme: 2013–2016. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC]. (2018). Drugs and age. Drugs and associated issues among young people and older people. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC]. (2020). Conducting effective substance abuse prevention work among the youth in South Africa. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. [Google Scholar]

- Van ZuI, A. E. (2013). Drug use amongst South African youths: Reasons and solutions. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(14), 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D., Mhlaba, M., Molelekeng, M., Chauke, T. A., Simao, S. C., Jenner, S., Ware, L. J., & Barker, M. (2023). How do we best engage young people in decision-making about their health? A scoping review of deliberative priority setting methods. International Journal for Equity Health, 22(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2014). World drug report 2014. World Health Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- Zemba, M. (2022). The causes and effects of drug abuse on pupils’ academic performance: A case study of Mindolo secondary school in Kitwe, Zambia. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Analysis, 5(08), 2253–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimonyo, T. (2020). Zimbabwe: Drug abuse-Soul Jah love seeks help. The Herald P1. [Google Scholar]

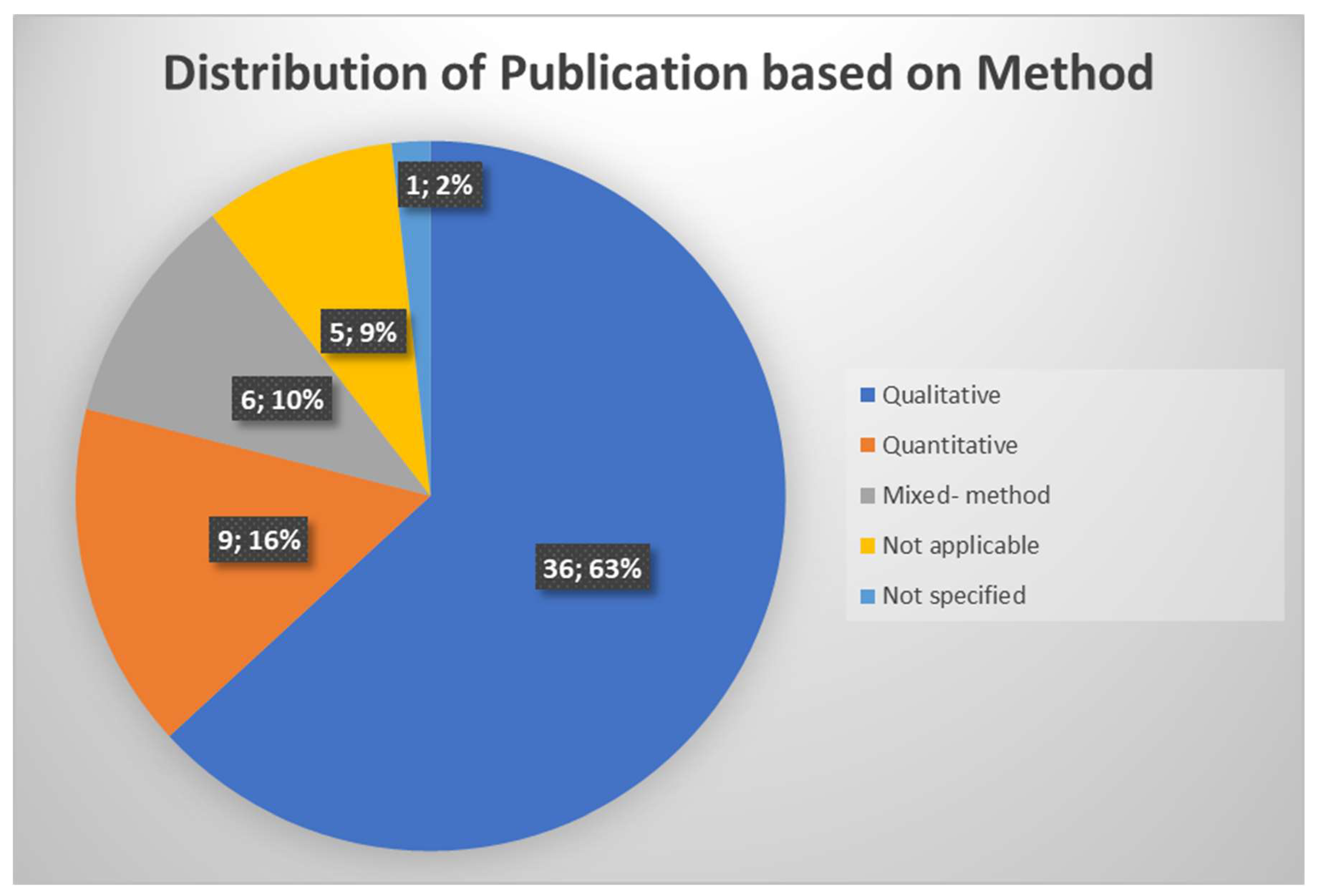

| Country | Author/s (Year) | Method | Key Issue |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC] (2013, 2020) | Mixed-method |

|

| Department of Social Development (2013) | Mixed-method | ||

| Machethe et al. (2022) | Qualitative | ||

| National Youth Policy (2021) | Qualitative | ||

| Mulaudzi (2018) | Qualitative | ||

| Setlalentoa et al. (2015) | Qualitative | ||

| Van ZuI (2013) | Mixed-method | ||

| Nyashanu and Visser (2022) | Qualitative | ||

| Ndawonde (2020) | Qualitative | ||

| Mudavanhu and Schenck (2014) | Mixed-method | ||

| Department of Social Development (2013). | Qualitative | ||

| Mixed-method | |||

| Ngcobo (2018) | Qualitative | ||

| Naidoo et al. (2016) | Qualitative | ||

| Muthelo et al. (2023) | |||

| Das et al. (2016) | Qualitative | ||

| Tomokawa et al. (2020) | |||

| Cupido (2017) | Qualitative | ||

| Saba et al. (2021) | Qualitative | ||

| Botswana | Riva et al. (2018) | Quantitative |

|

| Diraditsile and Rasesigo (2018) | Qualitative | ||

| Letamo et al. (2016) | Quantitative | ||

| Pitso and Obot (2011) | Qualitative | ||

| Zimbabwe | Dzinamarira et al. (2023) | Qualitative |

|

| Matutu and Mususa (2019) | Qualitative | ||

| Mukwenha et al. (2022) | Qualitative | ||

| Makwanise (2023) | Quantitative | ||

| Pufall et al. (2017) | Quantitative | ||

| Mahiya (2016) | Qualitative | ||

| Macheka and Masuku (2019) | Qualitative | ||

| Nhapi (2019) | Qualitative | ||

| Maraire et al. (2020) | Quantitative | ||

| Makande (2017) | Qualitative | ||

| Magaya (2017) | Qualitative | ||

| Nhapi and Mathende (2016) | Qualitative | ||

| Matunhu and Matunhu (2016) | Qualitative | ||

| Chikwanah (2019) | Not applicable | ||

| Kumuterera (2019) | Not applicable | ||

| Zimonyo (2020) | Not applicable | ||

| Grim and Grim (2019) | Qualitative | ||

| Koenig (2012) | Qualitative | ||

| Pearce (2016) | Not applicable | ||

| Maraire et al. (2022) | Qualitative | ||

| Namibia | Netope et al. (2023) | Quantitative |

|

| Strijdom (1992) | Quantitative | ||

| Zambia | Masiye and Ndhlovu (2015) | Qualitative |

|

| Shibalika and Chileshe (2022) | Qualitative | ||

| Mphande et al. (2023) | Qualitative | ||

| Zemba (2022) | Not specified | ||

| Ekpenyong (2012) | Quantitative | ||

| Masiye and Ndhlovu (2015) | Qualitative | ||

| Nyimbili et al. (2019) | Qualitative | ||

| Zemba (2022) | Mixed-method | ||

| Midford et al. (2000) | Qualitative | ||

| Mertens and Wilson (2012) | Not applicable | ||

| Eswatini | Mhlongo (2005) | Quantitative | Peer pressure and societal norms |

| Lesotho | Mofokeng (2013) | Qualitative | Poor academic performance linked to alcohol abuse. |

| Ranotsi et al. (2012) | Quantitative | ||

| Masihleho and Khalanyane (2009) | Qualitative |

| Country | Intervention |

|---|---|

| South Africa |

|

| Botswana |

|

| Zimbabwe |

|

| Namibia |

|

| Zambia |

|

| Eswatini |

|

| Lesotho |

|

| Country | Effectiveness |

|---|---|

| South Africa |

|

| Botswana |

|

| Zimbabwe | The National Drug Master Plan has been effective in reducing youth drug use through legal and social measures. |

| Namibia |

|

| Zambia |

|

| Eswatini | Successful in creating awareness and providing treatment. |

| Lesotho |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chauke, T.A.; Ndwandwe, N.D. A Scoping Review of Youth Development Measures to Mitigate Drug and Alcohol Abuse Among Young People in the SADC Region. Youth 2025, 5, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030092

Chauke TA, Ndwandwe ND. A Scoping Review of Youth Development Measures to Mitigate Drug and Alcohol Abuse Among Young People in the SADC Region. Youth. 2025; 5(3):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030092

Chicago/Turabian StyleChauke, Thulani Andrew, and Ntokozo Dennis Ndwandwe. 2025. "A Scoping Review of Youth Development Measures to Mitigate Drug and Alcohol Abuse Among Young People in the SADC Region" Youth 5, no. 3: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030092

APA StyleChauke, T. A., & Ndwandwe, N. D. (2025). A Scoping Review of Youth Development Measures to Mitigate Drug and Alcohol Abuse Among Young People in the SADC Region. Youth, 5(3), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030092