Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Migrant and Refugee Youth: An Exploratory Socioecological Qualitative Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

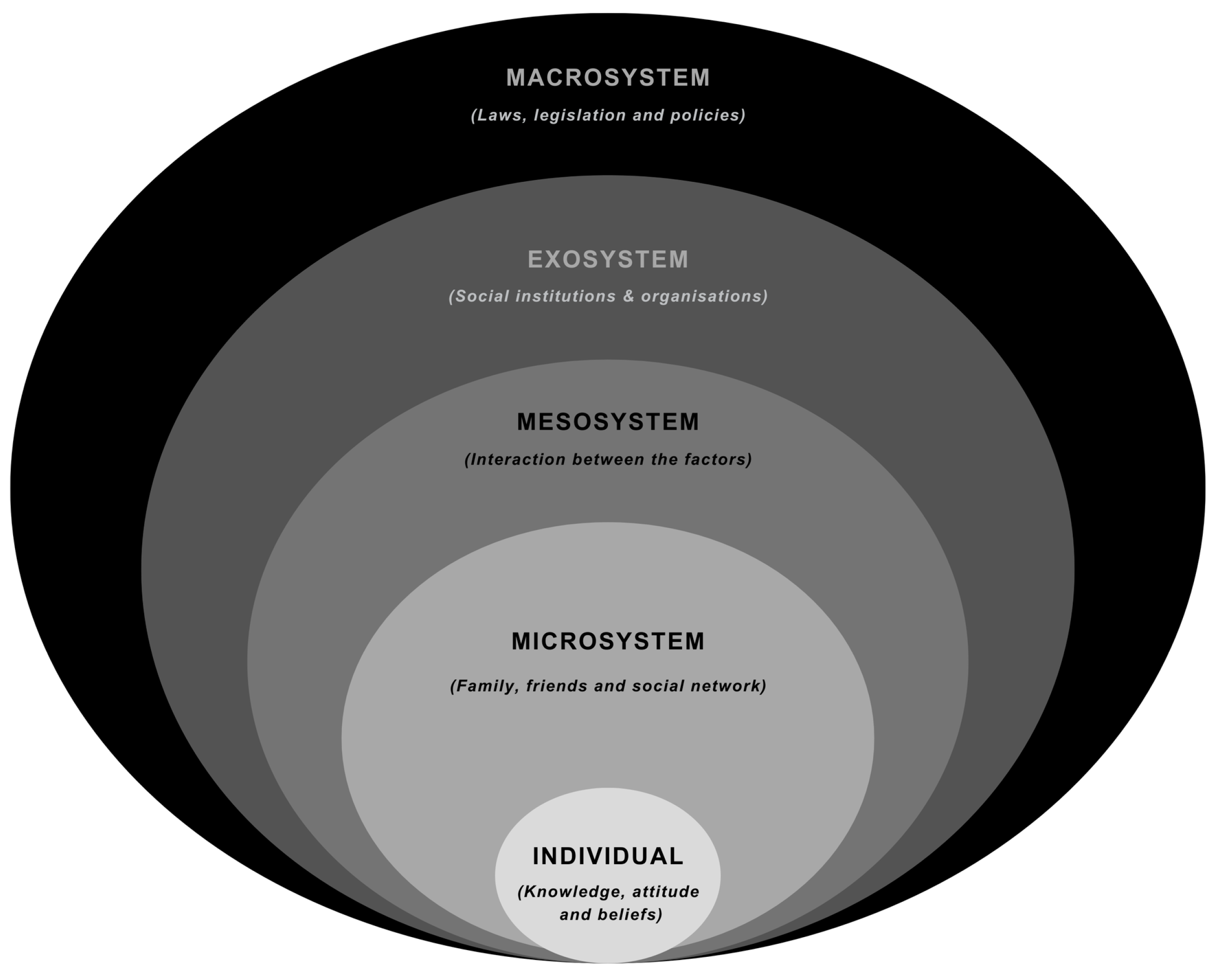

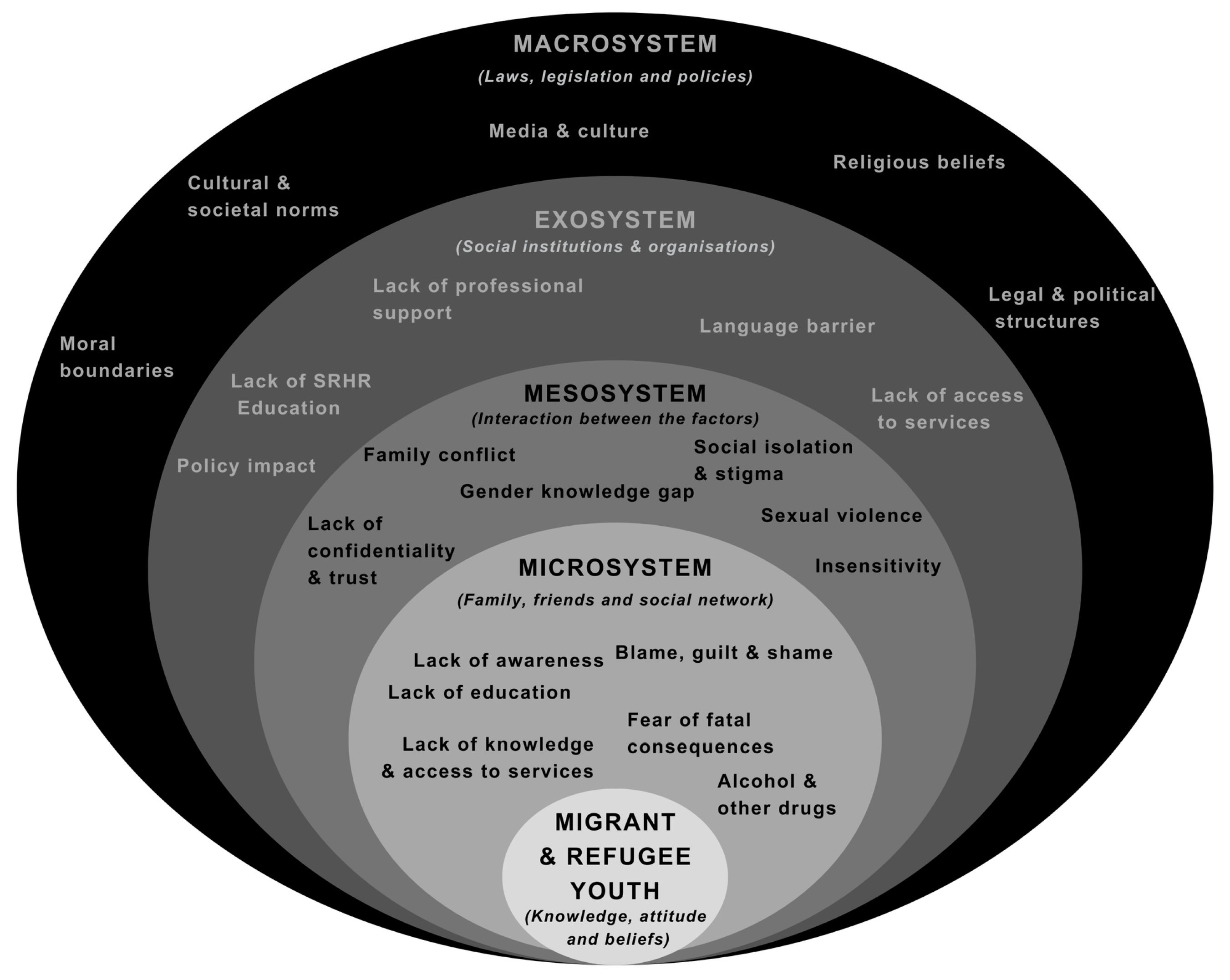

1.1. Theoretical Framework

The Socioecology of MRY’s Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment and Sample

2.2.1. Advisory Committee Members (ACMs)

2.2.2. Youth Project Liaisons (YPLs)

2.2.3. Migrant and Refugee Youth (MRY)

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Consent

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Microsystem Level

3.1.1. Lack of Awareness and Access to Services

3.1.2. Lack of SRHRs Education

3.1.3. Fear of Fatal Consequences

3.1.4. Blame, Guilt, and Shame

3.1.5. Alcohol and Other Drugs (AODs)

3.2. Mesosystem Level

3.2.1. Family Conflict

3.2.2. Social Isolation and Stigma

3.2.3. Gender Knowledge Gap

3.2.4. Sexual Violence

3.2.5. Lack of Confidentiality and Trust

3.2.6. Insensitivity

3.3. Exosystem Level

3.3.1. Lack of Professional Support

3.3.2. Language Barriers

3.3.3. Policy Impact

3.3.4. Lack of SRHRs Education in the Curriculum

3.3.5. Lack of Access to Services

3.4. Macrosystem Level

3.4.1. Cultural and Societal Norms

3.4.2. Religious Beliefs

3.4.3. Moral Boundaries

3.4.4. Media and Culture

4. Discussion

4.1. Microsystem Level

Recommendations for Practice

4.2. Mesosystem Level

4.2.1. Recommendations for Practice

4.2.2. Recommendations for Research

4.3. Exosystem Level

4.3.1. Recommendations for Practice

4.3.2. Recommendations for Research

4.3.3. Recommendations for Policy

4.4. Macrosystem Level

4.4.1. Recommendations for Practice

4.4.2. Recommendations for Theory

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | n = 75 a | % |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 56 | 74.67 |

| Male | 19 | 25.33 |

| Other | 0 | 0.00 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Straight | 63 | 84.00 |

| Bisexual | 5 | 6.67 |

| Gay | 0 | 0.00 |

| Pansexual | 2 | 2.67 |

| Asexual | 0 | 0.00 |

| Other or missing b | 5 | 6.67 |

| Religion | ||

| No religion | 10 | 13.33 |

| Christian | 30 | 40 |

| Catholic c | 11 | 14.67 |

| Buddhist | 6 | 8.00 |

| Greek Orthodox | 0 | 0.00 |

| Islamic | 6 | 8.00 |

| Other or missing d | 12 | 16.00 |

| Country of Birth | ||

| Australia | 38 | 50.67 |

| Nigeria | 7 | 9.33 |

| Fiji | 4 | 5.33 |

| New Zealand | 3 | 4.00 |

| Thailand | 3 | 4.00 |

| Iraq | 3 | 4.00 |

| Philippines | 2 | 2.67 |

| India | 2 | 2.67 |

| Zimbabwe | 2 | 2.67 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1.33 |

| Italy | 1 | 1.33 |

| Vietnam | 1 | 1.33 |

| Myanmar | 1 | 1.33 |

| Sierra Leone | 1 | 1.33 |

| England | 1 | 1.33 |

| Liberia | 1 | 1.33 |

| Egypt | 1 | 1.33 |

| Bangladesh | 1 | 1.33 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 1.33 |

| Malaysia | 1 | 1.33 |

| Mean (Std. dev.) | Range | |

| Age in years | 20.02 | 15–29 |

| a At the end of the focus group sessions, the participants were asked to complete a Qualtrics survey for additional demographic data collection. Of the 87 migrant and refugee youths participating in this study, 75 completed the survey. b Expressions, such as ‘unsure’, ‘anything goes’, and ‘questioning’, were used by the participants when describing their sexual orientation. It should also be noted that two participants opted not to share information regarding their sexual orientation. c The participants identified with various Christian denominations, including Baptist, Anglican, Pentecostal, Assyrian Orthodox, Coptic Orthodox, and Maronite Catholic. d Other religious affiliations reported by the participants included Agnostic, Spiritual, and Hindu affiliations. Furthermore, two participants did not report any information regarding religion. | ||

Appendix B

- What does the term sexual health mean to you?

- What does the term reproductive health mean to you?

- What are your human rights in relation to your sexual and reproductive health?

- What helps you to maintain and protect your sexual reproductive health?

- What stops you from being able to maintain or protect your sexual reproductive health?

- What needs to be done differently in Western Sydney to address these SRHR gaps?

References

- Iqbal, S.; Zakar, R.; Zakar, M.Z.; Fischer, F. Perceptions of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health and rights: A cross-sectional study in Lahore District, Pakistan. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2017, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, I.-H.; Advocat, J.R.; Vasi, S.; Enticott, J.C.; Willey, S.; Wahidi, S.; Crock, B.; Raghavan, A.; Vandenberg, B.; Gunatillaka, N.; et al. A Rapid Review of Evidence-Based Information, Best Practices and Lessons Learned in Addressing the Health Needs of Refugees and Migrants: Report to the World Health Organization April 2018; World Health Organization: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Human Rights and Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Starrs, A.; Ezeh, A.; Barker, G.; Basu, A.; Bertrand, J.; Blum, R.; Coll-Seck, A.M.; Grover, A.; Laski, L.; Roa, M.; et al. Accelerate Progress—Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for All: Report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2018, 391, 2642–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botfield, J.; Newman, C.; Anthony, Z.W.I. P4.51 Engaging young people from migrant and refugee backgrounds with sexual and reproductive health promotion and care in Sydney, Australia. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2017, 93, A210. [Google Scholar]

- Annual Report 2015–16; Family Planning Victoria: Victoria, Australia, 2016; ISSN 1839-549X.

- Botfield, J.R.; Newman, C.E.; Zwi, A.B. Young people from culturally diverse backgrounds and their use of services for sexual and reproductive health needs: A structured scoping review. Sex. Health 2016, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuyambe, L.; Kibira, S.P.S.; Bukenya, J.; Muhumuza, C.; Apolot, R.R.; Mulogo, E. Understanding sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents: Evidence from a formative evaluation in Wakiso District, Uganda. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleri, R.; Mapedzahama, V.; Pithavadian, R.; Firdaus, R.; Ayika, D.; Arora, A. Culturally and linguistically diverse Australians. In Diversity and Health in Australia; Cavaleri, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu, E.; Nkomazana, F.; Muchado, J.A.; Togarasei, L.; Bingenheimer, J.B. Faith and HIV prevention: The conceptual framing of HIV prevention among Pentecostal Batswana teenagers. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, B.; Cherrett, C.; Moryosef, L.; Lau, N.; Wykes, J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Knowledge amongst general practitioners in Western Sydney. J. Community Med. Health Educ. 2017, 7, 2106-0711. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, V.; Calgaro, E.; Dominey-Howes, D. The future of our suburbs: Analyses of heatwave vulnerability in a planned estate. Geogr. Res. 2021, 60, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Tirado, V.; Chu, J.; Hanson, C.; Ekström, A.M.; Kågesten, A. Barriers and facilitators for the sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people in refugee contexts globally: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganczak, M.; Czubińska, G.; Korzeń, M.; Szych, Z. A cross-sectional study on selected correlates of high-risk sexual behavior in Polish migrants resident in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakushko, O.; Watson, M.; Thompson, S. Stress and coping in the lives of recent immigrants and refugees: Considerations for counseling. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2008, 30, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dune, T.; Perz, J.; Mengesha, Z.; Ayika, D. Culture clash? Investigating constructions of sexual and reproductive health from the perspective of 1.5 generation migrants in Australia using Q methodology. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metusela, C.; Ussher, J.; Perz, J.; Hawkey, A.; Morrow, M.; Narchal, R.; Estoesta, J.; Monteiro, M. “In my culture, we don’t know anything about that”: Sexual and reproductive health of migrant and refugee women. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawson, H.A.; Liamputtong, P. Culture and sex education: The acquisition of sexual knowledge for a group of Vietnamese Australian young women. Ethn. Health 2010, 15, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J.; Metusela, C.; Hawkey, A.J.; Morrow, M.; Narchal, R.; Estoesta, J. Negotiating discourses of shame, secrecy, and silence: Migrant and refugee women’s experiences of sexual embodiment. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 1901–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulubwa, C.; Hurtig, A.-K.; Zulu, J.M.; Michelo, C.; Sandøy, I.F.; Goicolea, I. Can sexual health interventions make community-based health systems more responsive to adolescents? A realist-informed study in rural Zambia. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, O.; Rai, M.; Kemigisha, E. A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health knowledge, experiences and access to services among refugee, migrant and displaced girls and young women in Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2005, 29, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagitcibasi, C. Family, Self, and Human Development Across Cultures: Theory and Applications; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, P.; Sitharthan, G. Acculturation of Indian subcontinental adolescents living in Australia. Aust. Psychol. 2017, 52, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtamu, D.; Adamu, A. Assessment of sexual and reproductive health status of street children in Addis Ababa. J. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2013, 2013, 524076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herd, P.; Higgins, J.; Sicinski, K.; Merkurieva, I. The implications of unintended pregnancies for mental health in later life. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heslehurst, N.; Brown, H.; Pemu, A.; Coleman, H.; Rankin, J. Perinatal health outcomes and care among asylum seekers and refugees: A systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkey, A.; Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J. What do women want? Migrant and refugee women’s preferences for the delivery of sexual and reproductive healthcare and information. Ethn. Health 2021, 26, 782–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier-Raman, S.; Hossain, S.Z.; Lee, M.-J.; Mpofu, E.; Liamputtong, P.; Dune, T. Migrant and refugee youth perspectives on sexual and reproductive health and rights in Australia: A systematic review. Sex. Health 2023, 20, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z.B.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J.M. Refugee and migrant women’s engagement with sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: A socio-ecological analysis of health care professional perspectives. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riza, E.; Karnaki, P.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Zota, K.; Ho, M.; Petropoulou, M.; Katsas, K.; Garcés-Ferrer, J.; Linos, A. Determinants of refugee and migrant health status in 10 European countries: The Mig-HealthCare project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpofu, E. How religion frames health norms: A structural theory approach. Religions 2018, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amroussia, N. Providing sexual and reproductive health services to migrants in southern Sweden: A qualitative exploration of healthcare providers’ experiences. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Torres, L.; Svanemyr, J. Ensuring youth’s right to participation and promotion of youth leadership in the development of sexual and reproductive health policies and programs. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, S51–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Narasimhan, M.; Denison, J.A.; Kennedy, C.E. Achieving pregnancy safely for HIV-serodiscordant couples: A social ecological approach. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liamputtong, P. Researching the Vulnerable: A Guide to Sensitive Research Methods; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–256. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. The SAGE Handbook of Action Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong, P. Qualitative Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Victoria, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirkos, L. Quirkos; Quirkos Software: Edinburgh, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft, G.; Tansella, M.; Law, A. Steps, challenges, and lessons in developing community mental health care. World Psychiatry 2008, 7, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baigry, M.I.; Ray, R.; Lindsay, D.; Kelly-Hanku, A.; Redman-MacLaren, M. Barriers and enablers to young people accessing sexual and reproductive health services in Pacific Island countries and territories: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0278587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.B.; Wardle, J.; Steel, A.; Adams, J. An assessment of Ebola-related stigma and its association with informal healthcare utilisation among Ebola survivors in Sierra Leone: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.W.; Neal, Z.P. Nested or networked? Future directions for ecological systems theory. Soc. Dev. 2013, 22, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coatsworth, J.D.; Pantín, H.; McBride, C.K.; Briones, E.; Kurtines, W.M.; Szapocznik, J. Ecodevelopmental correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2002, 6, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malia, M.; Goleen, S.; Jennifer, O.; Clarisa, B.; Terry, M. ‘Scrambling to figure out what to do’: A mixed-method analysis of COVID-19’s impact on sexual and reproductive health and rights in the United States. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2021, 47, e16. [Google Scholar]

- Chattu, V.K.; Yaya, S. Emerging infectious diseases and outbreaks: Implications for women’s reproductive health and rights in resource-poor settings. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, M.; Al-Haidari, T.; Benedetto, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Christilaw, J.; El Kak, F.; Galimberti, D.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Gutierrez, M.; Ibrahim, S.; et al. How the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic is impacting sexual and reproductive health and rights and response: Results from a global survey of providers, researchers, and policymakers. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Okumu, M.; Mwima, S.P.; Kyambadde, P.; Hakiza, R.; Kibathi, I.P.; Kironde, E.; Musinguzi, J.; Kipenda, C.U. Exploring associations between adolescent sexual and reproductive health stigma and HIV testing awareness and uptake among urban refugee and displaced youth in Kampala, Uganda. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2019, 27, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnong, C.; Fellmeth, G.; Plugge, E.; Wai, N.S.; Pimanpanarak, M.; Paw, M.K.; Charunwatthana, P.; Nosten, F.; McGready, R. Adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of pregnancy in refugee and migrant communities on the Thailand-Myanmar border: A qualitative study. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.D.; Daniyal, M.; Abid, K.; Tawiah, K.; Tebha, S.S.; Essar, M.Y. Analysis of adolescents’ perception and awareness level for sexual and reproductive health rights in Pakistan. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pound, P.; Langford, R.; Campbell, R. What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? A qualitative synthesis of young people’s views and experiences. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.D.; Hutter, I.; Timmerman, G. Young people’s perceptions of relationships and sexual practices in the abstinence-only context of Uganda. Sex Educ. 2017, 17, 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, M.; Senn, T.E.; Carey, M.P. Fear of violent consequences and condom use among women attending an STD clinic. Women Health 2013, 53, 799–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wado, Y.D.; Bangha, M.; Kabiru, C.W.; Feyissa, G.T. Nature of, and responses to, key sexual and reproductive health challenges for adolescents in urban slums in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josefsson, K.A.; Schindele, A.C.; Deogan, C.; Lindroth, M. Education for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR): A mapping of SRHR-related content in higher education in health care, police, law, and social work in Sweden. Sex Educ. 2019, 19, 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Horyniak, D.; Melo, J.S.; Farrell, R.M.; Ojeda, V.D.; Strathdee, S.A. Epidemiology of substance use among forced migrants: A global systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, K.S.; Bauermeister, J.A.; Brackis-Cott, E.; Dolezal, C.; Mellins, C.A. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-exposed youth: Roles of caregivers, peers, and HIV status. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, H.; Xu, G.; Cai, Y.; Huang, F.; Ye, X. Substance use, risky sexual behaviors, and their associations in a Chinese sample of senior high school students. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirado, V.; Engberg, S.; Holmblad, I.S.; Strömdahl, S.; Ekström, A.M.; Hurtig, A.K. “One-time interventions, it doesn’t lead to much”—Healthcare provider views to improving sexual and reproductive health services for young migrants in Sweden. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corosky, G.J.; Blystad, A. Staying healthy “under the sheets”: Inuit youth experiences of access to sexual and reproductive health and rights in Arviat, Nunavut, Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2016, 75, 32685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengesha, Z.B.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J. Challenges in the provision of sexual and reproductive health care to refugee and migrant women: A Q-methodological study of health professional perspectives. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fair, F.; Soltani, H.; Raben, L.; Streun, Y.v.; Sioti, E.; Papadakaki, M.; Burke, C.; Watson, H.; Jokinen, M.; Shaw, E. Midwives’ experiences of cultural competency training and providing perinatal care for migrant women: A mixed-methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z.B.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J.M. Preparedness of health care professionals for delivering sexual and reproductive health care to refugee and migrant women: A mixed-methods study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Lobo, R.; Sorenson, A. Evaluating the Sharing Stories youth theatre program: An interactive theatre and drama-based strategy for sexual health promotion among multicultural youth. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2017, 28, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 6th ed.; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.-F.; Chang, Y.-P.; Lin, C.-Y.; Yen, C.-F. A newly developed scale for assessing experienced and anticipated sexual stigma in health-care services for gay and bisexual men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaaf, M.; Khosla, R. Necessary but not sufficient: A scoping review of legal accountability for sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e005298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.J.; McBain, K.A.; Li, W.W.; Raggatt, P.T.F. Pornography, preference for porn-like sex, masturbation, and men’s sexual and relationship satisfaction. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 26, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinew, Y.M.; Worku, A.; Mengesha, Z.B. Knowledge of reproductive and sexual rights among university students in Ethiopia: Institution-based cross-sectional. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2013, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veenstra, G. Race, gender, class, and sexual orientation: Intersecting axes of inequality and self-rated health in Canada. Int. J. Equity Health 2011, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, G.; Przedworski, J.; Henning-Smith, C. Comparison of health and health risk factors between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and heterosexual adults in the United States: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torke, A.M.; Carnahan, J.L. Optimizing the clinical care of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommet, N.; Berent, J. Porn use and men’s and women’s sexual performance: Evidence from a large longitudinal sample. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3144–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, P.J.; Paul, B.; Herbenick, D.; Tokunaga, R.S. Pornography and sexual dissatisfaction: The role of pornographic arousal, upward pornographic comparisons, and preference for pornographic masturbation. Hum. Commun. Res. 2021, 47, 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, G.; Bhugra, D. Sexual violence against women: Understanding cross-cultural intersections. Indian J. Psychiatry 2013, 55, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keygnaert, I.; Guieu, A. What the eye does not see: A critical interpretive synthesis of European Union policies addressing sexual violence in vulnerable migrants. Reprod. Health Matters 2015, 23, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, T.V.; Mugavin, J.; Renzaho, A.M.N.; Lubman, D.I. Sub-Saharan African migrant youths’ help-seeking barriers and facilitators for mental health and substance use problems: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, L.; Moorhead, A.; Long, M.; Hawthorne-Steele, I. What type of helping relationship do young people need? Engaging and maintaining young people in mental health care—A narrative review. Youth Soc. 2021, 53, 1376–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheen, H.; Chalmers, K.; Khaw, S.; McMichael, C. Sexual and reproductive health service utilisation of adolescents and young people from migrant and refugee backgrounds in high-income settings: A qualitative evidence synthesis (QES). Sex. Health 2021, 18, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohodes, E.M.; Kribakaran, S.; Odriozola, P.; Bakirci, S.; McCauley, S.; Hodges, H.R.; Sisk, L.M.; Zacharek, S.J.; Gee, D.G. Migration-related trauma and mental health among migrant children emigrating from Mexico and Central America to the United States: Effects on developmental neurobiology and implications for policy. Dev. Psychobiol. 2021, 63, e22158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.M.; Rubinstein, T.; Rodriguez, M.; Knight, A. Mental health care for youth with rheumatologic diseases—Bridging the gap. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2017, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mmari, K.; Lantos, H.; Brahmbhatt, H.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Lou, C.; Acharya, R.; Sangowawa, A. How adolescents perceive their communities: A qualitative study that explores the relationship between health and the physical environment. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulu, J.M.; Goicolea, I.; Kinsman, J.; Sandøy, I.F.; Blystad, A.; Mulubwa, C.; Makasa, M.C.; Michelo, C.; Musonda, P.; Hurtig, A.-K. Community-based interventions for strengthening adolescent sexual reproductive health and rights: How can they be integrated and sustained? A realist evaluation protocol from Zambia. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aibangbee, M.; Micheal, S.; Mapedzahama, V.; Liamputtong, P.; Pithavadian, R.; Hossain, Z.; Mpofu, E.; Dune, T. Migrant and refugee youth’s sexual and reproductive health and rights: A scoping review to inform policies and programs. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 68, 145676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.; Crawford, G.; Maycock, B.; Lobo, R. Socioecological factors influencing sexual health experiences and health outcomes of migrant Asian women living in ‘Western’ high-income countries: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami-Aghdash, S.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Sheyklo, S.G.; Daemi, A.; Kolahdouzan, K.; Mohseni, M.; Moosavi, A. Breast cancer screening barriers from the woman’s perspective: A meta-synthesis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 3463–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderWielen, L.M.; Enurah, A.S.; Rho, H.Y.; Nagarkatti-Gude, D.R.; Michelsen-King, P.; Crossman, S.H.; Vanderbilt, A.A. Medical interpreters: Improvements needed for training, testing, and tracking. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruane-McAteer, E.; Amin, A.; Hanratty, J.; Lynn, F.; van Willenswaard, K.C.; Reid, E.; Khosla, R.; Lohan, M. Interventions addressing men, masculinities, and gender equality in sexual and reproductive health and rights: An evidence and gap map and systematic review of reviews. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, S.; Maddams, A.; Lowe, H.; Davies, L.; Khosla, R.; Shakespeare, T. From words to actions: Systematic review of interventions to promote sexual and reproductive health of persons with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, N.; Mactaggart, I.; Huggett, C.; Pheng, P.; Rahman, M.-U.; Biran, A.; Wilbur, J. The inclusion of rights of people with disabilities and women and girls in water, sanitation, and hygiene policy documents and programs of Bangladesh and Cambodia: Content analysis using EquiFrame. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, E.; Jones, R.; Tipene-Leach, D.; Walker, C.; Loring, B.; Paine, S.-J.; Reid, P. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatay, G.; Bowers, B.J.; Karadağ, E.; Demir, M. Cultural perceptions and clinical experiences of nursing students in Eastern Turkey. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonne, B.; Flemington, T.; Lock, M.; Hartz, D.; Ramanathan, S.; Fraser, J. The power of authenticity and cultural safety at the intersection of healthcare and child protection. Int. J. Child Maltreatment Res. Policy Pract. 2020, 3, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, W.; Thomas, R.; Barton, G.; Graham, I.D. Providing culturally safe cancer survivorship care with Indigenous communities: Study protocol for an integrated knowledge translation study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks-Cleator, L.A.; Phillipps, B.; Giles, A.R. Culturally safe health initiatives for Indigenous peoples in Canada: A scoping review. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 50, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, W.; Dick, P.; Larocque, C.; Modanloo, S.; Wazni, L.; Awar, Z.A.; Benoit, M. What culturally safe cancer care means to Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2023, 19, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseby, R.; Adams, K.; Leech, M.; Taylor, K.; Campbell, D. Not just a policy; this is for real: An affirmative action policy to encourage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to seek employment in the health workforce. Intern. Med. J. 2019, 49, 908–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asekun-Olarinmoye, O.S.; Asekun-Olarinmoye, E.O.; Adebimpe, W.O.; Omisore, A.G. Effect of mass media and internet on sexual behavior of undergraduates in Osogbo metropolis, Southwestern Nigeria. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2014, 5, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbarushimana, V.; Conco, D.N.; Goldstein, S. “Such conversations are not had in the families”: A qualitative study of the determinants of young adolescents’ access to sexual and reproductive health and rights information in Rwanda. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aylward, E.; Halford, S. How gains for SRHR in the UN have remained possible in a changing political climate. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2020, 28, 1758443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwankye, S.O.; Augustt, E. Media exposure and reproductive health behaviour among young females in Ghana. Afr. Popul. Stud. 2013, 27, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazard, B.; Chui, Z.; Harber-Aschan, L.; MacCrimmon, S.; Bakolis, I.; Rimes, K.; Hotopf, M.; Hatch, S.L. Barrier or stressor? The role of discrimination experiences in health service use. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, L.; Gazard, B.; Aschan, L.; MacCrimmon, S.; Hotopf, M.; Hatch, S.L. Taking an intersectional approach to define latent classes of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and migration status for psychiatric epidemiological research. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 26, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, C.; Tremblay, J.; Pomerleau, J.; Simard, M.; Bourgeois-Guérin, E.; Lyke, C.; Rousseau, C. Building communities in tense times: Fostering connectedness between cultures and generations through community arts. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 65, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C.; Xavier, L.L.; Andrade, C.; Ferreira, T.; Noronha, C.; Wainwright, T.; de Matos, M.G. “We are concerned about the future and we are here to support the change”: Let’s talk and work together! Children 2022, 9, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSER; Ogbe, E.; Van Braeckel, D.; Temmerman, M.; Larsson, E.C.; Keygnaert, I.; Aragón, W.D.L.R.; Cheng, F.; Lazdane, G.; Cooper, D.; et al. Opportunities for linking research to policy: Lessons learned from implementation research in sexual and reproductive health within the ANSER network. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, É.; Hinner, J.; Kruse, A. Potentials of survivors, intergenerational dialogue, active ageing and social change. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 214, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulin, A.J.; Dale, S.K.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Fava, J.L.; Mugavero, M.J.; Napravnik, S.; Hogan, J.W.; Carey, M.P.; Howe, C.J. Resilience and HIV: A review of the definition and study of resilience. AIDS Care 2018, 30, S6–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, A.L.; Stall, R.; Goldhammer, H.; Egan, J.E.; Mayer, K.H. Resilience as a research framework and as a cornerstone of prevention research for gay and bisexual men: Theory and evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prather, C.; Fuller, T.R.; Marshall, K.J.; Jeffries, W.L. The impact of racism on the sexual and reproductive health of African American women. J. Women’s Health 2016, 25, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Groups | Inclusion Criteria |

| Migrants and refugee youth |

|

| |

| |

| Youth project liaisons |

|

| |

| Advisory committee members |

|

| |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aibangbee, M.; Micheal, S.; Liamputtong, P.; Pithavadian, R.; Hossain, S.Z.; Mpofu, E.; Dune, T.M. Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Migrant and Refugee Youth: An Exploratory Socioecological Qualitative Analysis. Youth 2024, 4, 1538-1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040099

Aibangbee M, Micheal S, Liamputtong P, Pithavadian R, Hossain SZ, Mpofu E, Dune TM. Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Migrant and Refugee Youth: An Exploratory Socioecological Qualitative Analysis. Youth. 2024; 4(4):1538-1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040099

Chicago/Turabian StyleAibangbee, Michaels, Sowbhagya Micheal, Pranee Liamputtong, Rashmi Pithavadian, Syeda Zakia Hossain, Elias Mpofu, and Tinashe Moira Dune. 2024. "Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Migrant and Refugee Youth: An Exploratory Socioecological Qualitative Analysis" Youth 4, no. 4: 1538-1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040099

APA StyleAibangbee, M., Micheal, S., Liamputtong, P., Pithavadian, R., Hossain, S. Z., Mpofu, E., & Dune, T. M. (2024). Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Migrant and Refugee Youth: An Exploratory Socioecological Qualitative Analysis. Youth, 4(4), 1538-1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040099